the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Circular economy approach in phosphorus fertilization based on vivianite must be tailored to soil properties

Tolulope Ayeyemi

Ramiro Recena

Ana María García-López

José Manuel Quintero

María Carmen del Campillo

Antonio Delgado

Although there is relevant knowledge based on the effect of soil properties on the efficiency of common commercial fertilizers, this effect remains poorly understood for the use of vivianite from water purification as an innovative P fertilizer meeting a circular economy approach. This study aimed to evaluate the effect of soil properties on the efficiency of vivianite recovered from water purification as a P fertilizer and to provide practical recommendations for its effective use. Vivianite and a soluble mineral P fertilizer (superphosphate) were compared at two P application rates (50 and 100 mg P kg−1) in soils ranging widely in properties in a pot experiment using wheat. Soluble P fertilizer provided the best results in terms of dry matter (DM) yield, P uptake, and Olsen P in soils, while vivianite led to the best results of DTPA extractable Fe in soils after crop harvest. The application of vivianite as a P fertilizer was more efficient in acidic soils (pH<6.6). The effect of vivianite on dry matter (DM) yield was equivalent on average to 26 or 40 %, depending on the rate, of the same amount of soluble fertilizer in these acidic soils (i.e., P fertilizer replacement value – PFRV – on DM basis), it being around 50 % in some cases. The effect on Olsen P in soil was equivalent, on average, to 49 or 61 %, depending on the rate, of the same amount applied as soluble mineral fertilizer in acidic soils. This can be explained by the increased solubility of this fertilizer product under acidic conditions, supported by the highest increase in DTPA extractable Fe in these soils. Acidic soils were those with initial Olsen P below the threshold value for fertilizer response (TV). However, PFRV on different approaches (DM, P uptake, and Olsen P) decreased more consistently with increased values of the difference between initial Olsen P and TV (46 % to 87 % of the variance explained) than with increased pH. This reveals that, besides soil pH, a low P availability to plants can trigger plant and microbial mobilization mechanisms, leading to increased efficiency of vivianite as a P fertilizer. These results are promising for the use of vivianite from wastewater treatment as a P fertilizer, the application of which should be adapted to the soil properties, and is especially recommended for acidic P-deficient soils.

- Article

(547 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(574 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Phosphorus (P) is an essential nutrient required for optimal crop production (Balemi and Negisho, 2012; Sharma et al., 2013; Recena et al., 2017). Phosphorus fertilizers are majorly derived from phosphate rock (PR), which is a non-renewable and strategic resource (Recena et al., 2022; Ayeyemi et al., 2023, 2024). Currently, 82 % of PR is used for manufacturing phosphate fertilizers (Schröder et al., 2010; Heckenmüller et al., 2014). Phosphate rock production is expected to peak in the current century (Cordell et al., 2009; Keyzer, 2010), posing a serious constraint to global food security. The recent discovery of huge PR deposits in Norway (The Economist, 2023; Hernández-Mora et al., 2024) would allow us to think about a change in the situation concerning the use of P resources. However, new industrial uses (e.g. production of batteries) would lead to an increase in consumption of this non-renewable resource, with expected constraints for agricultural production (García-López et al., 2025). Thus, ensuring food security for an increasing world population, with an estimated rise to nine billion by 2050 (United Nations, 2017), makes it crucial to explore alternative sources of P fertilizers aside from PR to support crop production.

The productivity of soils is dependent on their physical, chemical, and biological properties (Delgado and Gómez, 2016; Bibi et al., 2023), which are widely different globally due to soil-forming factors and processes (Mahdi and Uygur, 2018). These properties and their interactions govern the availability of nutrients in the soil rhizosphere (Jiang et al., 2009). Soil properties determine the reaction of applied fertilizers depending on their chemical form and, consequently, the response of crops to their application (Bindraban et al., 2015). Hence, crops grown on different soils respond differently to fertilizer application (Olaniyan et al., 2011). It is well-known that P adsorption and precipitation in soils are strongly dependent on their physical and chemical properties, such as texture, soil pH, iron (Fe) and aluminium (Al) oxides, organic matter, and carbonates (Pizzeghello et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2022a). Thus, these properties affecting P reactions in soil, together with the nature of fertilizers, will determine the use of applied P by crops (Delgado and Scalenghe, 2008). Organic P present in soil or applied as fertilizers can also be a direct source of available P through its mineralization and the turnover of microbial biomass (Recena et al., 2015, 2018; Bueis et al., 2019). Thus, the introduction of new and alternative P fertilizer products into cropping systems should consider the significant role that soil properties play in the reactions of P and, consequently, in the availability of native and applied P in soils. Regarding P fertilizer application, the definition of threshold values for a given soil P test, such as the Olsen P test, is necessary to predict crop yield response to fertilizer application (Recena et al., 2016, 2022). The threshold value is the limit of the soil P test above which soils are not responsive to P fertilizer application (Syers et al., 2008). This is sometimes referred to as the P-critical value. An efficient use of P from an agronomic and environmental standpoint can be achieved if the P threshold value is taken into account in P fertilizer strategies and management (Syers et al., 2008).

A sustainable strategy to manage P resources is through the recycling of P from all current waste streams throughout the whole food system, including production, processing and consumption (Cordell et al., 2009; Recena et al., 2022). Urban wastewater constitutes an important source of recoverable phosphorus, potentially contributing 15 %–20 % towards meeting the global yearly phosphorus demand (Wu et al., 2019). Nowadays, in the European Union (EU), recovered P from wastewater currently displaces only about 0.5 % of the use of conventional phosphate fertilizers, although the maximum potential is estimated at up to 13 % of total EU phosphate fertilizer imports (Muys et al., 2021; Recena et al., 2022; Soo and Shon, 2024). Therefore, it is highly relevant to consider the importance of P recovery from wastewater for phosphorus sustainability in the EU, in alignment with the 5R strategy proposed by Withers et al. (2015) for sustainable P management. Vivianite, an Fe2+ phosphate mineral (Fe3(PO4)2.8H2O), forms under reducing conditions in wastewater treatment facilities (Wilfert et al., 2018), aquatic sediments, drained agricultural areas (Egger et al., 2015; Dijkstra et al., 2016; Rothe et al., 2014), and in waterlogged soils (Heiberg et al., 2012; Nanzyo et al., 2013). Vivianite is now gaining attention as a potential P fertilizer (Fodoué et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2019), although its phosphorus content, around 10 %, depends on its crystallinity and the recovery methods employed. A recent study by Ayeyemi et al. (2023) revealed that industrially produced vivianite has a replacement value, i.e. an equivalence in dry matter production, to 50 %–75 % of the same amount of superphosphate. Eshun et al. (2024) demonstrated that vivianite produced with the use of Fe-reductant microorganisms was an efficient P fertilizer. Fodoué et al. (2015) and Jowett et al. (2018) found that vivianite application enhanced the growth and yield of bean and maize plants, respectively, and showed that P recovered from wastewater in the form of vivianite was equivalent or even superior to conventional superphosphate fertilizers. Vivianite can offer several advantages over conventional phosphate fertilizers, primarily by addressing the relatively low P uptake and use efficiency in crops, which often leads to overuse of soluble phosphate fertilizers and the resulting environmental impact and waste of this non-renewable resource (Monreal et al., 2016). Besides, vivianite may have a more favorable impact on soil microbial activity. A recent study by Faller et al. (2025) indicates that vivianite can act as a sustainable phosphate fertilizer that preserves the microbial potential for P cycling, promoting microbial taxa associated with P availability without significantly altering soil microbial community composition. This contrasts with mineral phosphorus fertilizers, which tend to affect the soil microbial communities, including P mobilizing bacteria (Liu et al., 2024; Deinert et al., 2025). However, the extraction costs of vivianite can exceed those of conventional fertilizer production, posing a disadvantage to its use. Xie et al. (2023) demonstrated through a comprehensive life-cycle analysis that the social costs associated with vivianite application are equal to or even lower than those of conventional phosphate fertilizer use.

Despite its potential, limited information is available on vivianite as a phosphate fertilizer, and the influence of soil properties on its effectiveness remains largely unknown. Soil environmental conditions are dynamic and heterogeneous, exerting significant influence on the redox transformation of iron minerals, a process closely linked to phosphorus mobilization and immobilization (Strong et al., 2004; Or et al., 2007; Peth et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2022). In this study, we investigated the impact of soil properties on the effectiveness of vivianite obtained from water purification as a P fertilizer using a pot experiment. We aimed to (1) evaluate the efficiency of using vivianite compared to mineral fertilizer based on the P fertilizer replacement value (PFRV); (2) explore the major properties of soil affecting P dynamics of vivianite; and (3) identify how dissolution of vivianite affects P availability to plants. This will allow us to demonstrate the possible use of vivianite as a P fertilizer under different soil conditions, leading to proper recommendations of its usage depending on soil properties.

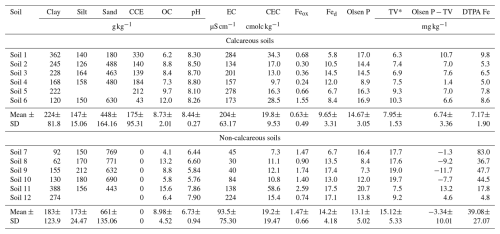

2.1 Soils

Twelve soil samples were collected from the surface horizon of typical soils developed under the Mediterranean climate. According to the Soil Taxonomy (Soil Survey Staff, 2014), selected soils were classified into Inceptisols, Alfisols, Vertisols, and Mollisols. This selection included calcareous and non-calcareous soils. In each selected location, a square of 10 m×10 m was defined with homogeneous surface properties in terms of color, texture, and structure. Then, 10–12 subsamples of the surface layer (0–20 cm) were randomly taken at sampling points. To this end, in each sampling point (1 m2), eight soil cores (50 mm diameter) were taken to obtain a subsample, and after that, all the subsamples from each sampling point were mixed to obtain a composite sample. The soils were air-dried, clods and lumps broken, and thereafter passed through a 2 mm sieve for laboratory analysis and sieved to <4 mm for pot experiment to avoid excessive destruction of soil structure that may affect crop performance in pots. Soils were analyzed for particle size distribution according to Gee and Bauder (1986), organic C by the oxidation method of Walkley and Black (1934), total CaCO3 equivalent (CCE) by the calcimeter method, pH, and electrical conductivity in water at a soil: extractant ratio of 1:2.5, and the cation exchange capacity (CEC) by using 1 M NH4OAc buffered at pH 7 (Sumner and Miller, 1996). Oxalate extraction was performed to release Fe in poorly crystalline Fe oxides (Feox), and citrate-bicarbonate-dithionite to release Fe in crystalline oxides (Fed) according to Recena et al. (2015). Olsen P was used as a soil P test, i.e, an availability index to assess the response to P fertilizer. It was determined by weighing two grams of soil into 50 mL Falcon tubes, after which 40 mL of 0.5 M NaHCO3 at pH 8.5 was added. The mixture was shaken in a mechanical end-over-end shaker for 30 min at 180 rpm. Subsequently, the suspension was centrifuged for 10 min at 900 g. The P concentration of the extract was determined by the colorimetric method of Murphy and Riley (1962) using a spectrophotometer at 882 nm. The DTPA (Diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid) extractable Fe determination was carried out according to Lindsay and Norvell (1978) with slight modifications as Fe availability index. To this end, five grams of soil were weighed into 50 mL Falcon tubes, and 20 mL of TEA (triethanolamine) was added. This suspension was stirred for 2 h at 160 rpm. The suspension was then placed in the centrifuge for 15 min at 900 g. The Fe concentration of the extract was determined by atomic absorption spectrometry. Since the soils have very different properties, it is expected that the Olsen P threshold value (TV), i.e., the value above which no response in yield is expected with P fertilization, ranges widely among soils (Recena et al., 2016). This TV was calculated according to the model proposed by Recena et al. (2022). The equation of the model is . To assess the available P status of soils, the Olsen P value was compared with the specific TV for each soil. The more negative this difference between current Olsen P in soil and TV (Olsen P−TV) is, the more deficient the soil is in P. The detailed properties of the soils used in this experiment are shown in Table 1.

Table 1Soil Properties.

CCE. Ca carbonate equivalent; ACCE. active Ca carbonate equivalent; EC. electrical conductivity; OC. organic carbon, CEC. cation exchange capacity; Ca. Mg. K. and Na. exchangeable cations; Feox. oxalate extractable Fe; Fed. citrate-bicarbonate-ditthionite extractable Fe; DPTA Fe. * TV. Threshold Value calculated as: (Recena et al., 2022).

2.2 Fertilizers

Two fertilizer products were studied in this experiment: (i) Water Purification Vivianite (WPV) obtained from Wetsus (European Centre of Excellence for Sustainable Water Technology) from Leeuwarden, the Netherlands, and (ii) Superphosphate as a reference P fertilizer: Ca(H2PO4)2.H2O.

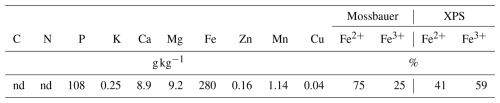

The elemental composition of the WPV (Table 2) was determined by ICP-OES after acid digestion, except for C and N; these two elements were determined in an elemental analyzer. The Fe2+ to Fe3+ ratio was determined by Mossbauer spectroscopy and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). This ratio is relevant since Fe3+ compounds are less soluble and contribute little to nutrient supply to crops (Ayeyemi et al., 2023).

2.3 Experimental Design

A pot experiment was conducted using durum wheat (Triticum durum L. cv. Amilcar) under controlled conditions in a growing chamber. The experiment was arranged in a Randomized Complete Block Design (RCBD) with three replicates. Each replicate corresponded to a pot with one wheat plant. Two factors were involved in the experiment: Soil type (12) and P fertilizer treatment, involving the two fertilizers described above, at two rates (50 and 100 mg P kg−1), and a non-fertilized control. The lowest P rate was selected since it is generally believed that plants respond to fertilizer application at this rate in P-poor growing media in pot experiments (García-López et al., 2016). The highest rate was chosen to check the impact of a high rate on P absorption and availability in the growing medium.

The growing media was prepared by mixing fertilizer products with 300 g of soil and placed in cylindrical polyethylene pots with a volume of 350 mL (height 150 mm; diameter 55 mm). The mixing of fertilizer products (in powder form) with soil was carried out 3 d before transplanting the wheat seedlings. Wheat seeds were pregerminated by sowing in a nursery for 15 d, after which they were transplanted into already prepared growing assays. The assay was placed in the growing chamber with temperatures of 25 °C/16 °C day/night and irrigation till 70 % of the water holding capacity of the soils, with replenishment by weight loss. Within the first 2 d of transplanting the wheat seedlings, irrigation was conducted only with water, after which a P-free nutrient solution (Hoagland type) was applied on a regular basis. The composition of this nutrient solution was (all concentrations in mmol L−1): MgSO4 (2), Ca(NO3)2 (5), KNO3 (5), KCl (0.05), Fe-EDDHA (0.02), H3BO3 (0.024), MnCl2 (0.0023), CuSO4 (0.0005), ZnSO4 (0.006), and H2MoO4 (0.0005). The wheat plants were harvested 58 d after transplanting at the ripening stage.

2.4 Collection of Soil and Plant Samples

At the end of the experiment, bulk soil samples (the entire soil samples in the pots) were collected for Olsen P and DTPA Fe analyses as described above. These samples were dried and milled to pass through a 2 mm screen. The roots and shoots of the wheat plants were also collected separately. Wheat root and shoot plant samples were placed in a forced-air oven dryer at 65 °C for 72 h, after which the dry matter (DM) in each organ was determined.

Plant Samples Analysis

Root and shoot wheat samples were ground. Subsequently, wet acid digestion was carried out. To this end, 50 mg of plant materials were placed in glass test tubes, and 1 mL HNO3 was added. The mixture was left to stand overnight. This was placed in an open block digest the next morning and heated to temperatures of 120–130 °C until the plant materials were fully digested and clear. This was made up to the 10 mL mark with Milli-Q water and allowed to stand overnight, after which the P concentration in the digest was determined by ICP-OES. The total P uptake by plants was determined as the sum of the product of the dry weight of each organ and its P concentration. The P fertilizer replacement value (PFRV) of vivianite was adapted from Hijbeek et al. (2018) as the amount of commercial mineral P fertilizer (superphosphate) saved or replaced when using an alternative fertilizer (in this case, vivianite) while attaining the same yield, P uptake, or Olsen P in soils. This gives an idea of equivalence if expressed on a percentage basis. It is expressed as the kg of commercial mineral fertilizer that provides the same effect as 100 kg of alternative fertilizer. Thus, it can be interpreted as the percentage of commercial mineral fertilizers that can be replaced by alternative fertilizers. It was estimated on a DM basis for each P rate following Eq. (1):

where DMv is the DM yield with vivianite, DMc is the average DM in the non-fertilized control, and DMs, the average DM in the superphosphate treatment at the same P rate as vivianite.

The PFRV was estimated on a P uptake basis for each P rate following Eq. (2):

Where Puptakev is the P uptake by crop with vivianite, Puptakec is the average P uptake in the non-fertilized control, and Puptakes, the average P uptake in the superphosphate treatment at the same P rate as vivianite.

The PFRV was also estimated on an Olsen P basis following Eq. (3):

where Olsen Pv is the Olsen P with vivianite, Olsen Pc is the average Olsen P of the non-fertilized control and Olsen Ps, the average Olsen P in the superphosphate treatment at the same rate as vivianite

2.5 Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with Statgraphics Centurion 18 (StatPoint Technologies, 2017). The effect of factors (P fertilizer treatment and soils as fixed factors) on DM yield and P uptake was assessed by means of a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). To assess the effect of soil on the different PFRV indices studied and the increase of DTPA extractable Fe, one-way ANOVA was performed for each P rate independently. Before ANOVA, normality and homogeneity of variance were assessed with the use of the Smirnov–Kolmogorov and Levene tests, respectively. Power transformations were performed when one or both tests were not passed. Mean separation was conducted using the Tukey Honest Significant Difference (HSD) test at P<0.05. If the interaction between factors was significant, the effects of the main factors were not discussed since the effect of one factor depends on the level of the other. To assess the differences in PFRV indices and increase in DTPA extractable Fe between calcareous and non-calcareous soils, an ANOVA with the factor soil type (i.e. calcareous or non-calcareous) was performed and means compared according to the Tukey test as above. To assess the differences between soils with pH<6.6 (n=4) and those with pH>7.86 (n=8), the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was performed. In this case, medians were compared according to the procedure of Bonferroni. Regression and correlation analysis were performed using the same software to see relationships between different soil properties.

3.1 Soil Properties

There was wide variation in the properties of the set of soils used in this experiment (Table 1), especially clay content and calcium carbonate equivalent (CCE), which are relevant properties affecting P dynamics in soils. The 12 soils used were grouped into two broad categories: six calcareous and six non-calcareous. The pH of the non-calcareous soils varied from 5.76 to 7.90, while in the calcareous soils, it ranged from 8.10 to 8.80. The DTPA extractable Fe content of the calcareous soils ranged from 5.0 to 9.8 mg kg−1, while those of non-calcareous soils were higher, ranging from 4.8 to 83.0 mg kg−1. The organic matter content of all soils varied from 4.1 to 15.6 g kg−1, while the clay content of all soils varied from 62 to 388 g kg−1. There was also a wide variation in the Olsen P value of the soils from 7.3 to 20.7 mg kg−1. The Olsen P−TV of the calcareous soils ranged from 1.4 to 10.7, while those of non-calcareous soils ranged from −11.7 to 13.2. The Olsen P−TV values were positively correlated with pH (r=0.83; P<0.001) and clay content (r=0.77; P<0.01). The four non-calcareous soils with pH lower than 6.6 were the soils with negative values of Olsen P−TV. The oxalate and dithionite extractable Fe were negatively correlated with carbonate content ( and −0.59, respectively; P<0.05 in both cases).

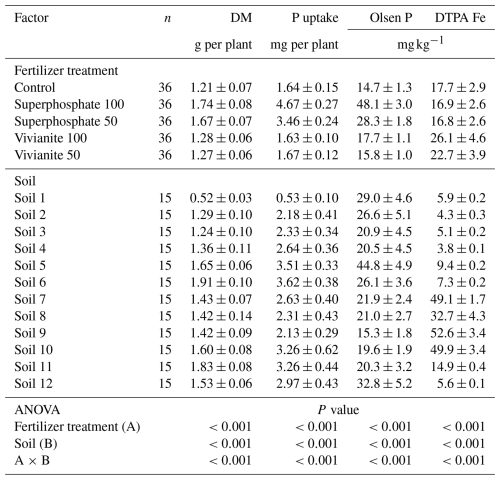

3.2 Effect of Soils and Fertilizer Treatments on Crops and Soil

The dry matter (DM) yield, total P uptake by plants, and Olsen P and DTPA extractable Fe in the soil after crop harvest were significantly affected by the interaction between both factors, soil and fertilizer treatment (P<0.001 in all cases; Table 3). This means that the effect of fertilizer treatments depends on soil. Overall, soluble mineral fertilizer (superphosphate) provided the best results in terms of DM, P uptake, and Olsen P; meanwhile, vivianite led to the best results of DTPA extractable Fe in soil after crop harvest (Table 3). The vivianite treatments led to increased DM yield relative to non-fertilized control in soils 8, 3, 9 and 10 (Table S1 in the Supplement). In these soils and in soil 3, vivianite treatments slightly increased P uptake when compared with the control (Table S1). In soils 8, 3, 7, 9 and 10, vivianite led to higher Olsen P after crop harvest than control, and in soils 9 and 10, the highest rate of vivianite promoted higher Olsen P than the lowest rate of mineral soluble P fertilizer (Table S1). The increase of DTPA extractable Fe with vivianite relative to superphosphate and control was particularly evident in soils 8, 9, and 10 (Table S1).

Table 3Effect of fertilizer treatments and soil on dry matter yield (DM) and P uptake by crop. and Olsen P and DTPA extractable Fe after crop harvest.

Mean ± standard error

Number after fertilizer indicates the P rate in mg kg−1 of soil

Mean comparison is not performed since the interaction of both factors is significant. In that case, the effect of one factor depends on the other and an analysis of the effect of main factor cannot be performed.

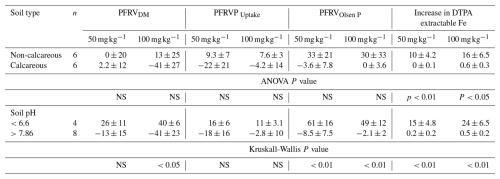

With vivianite at 50 mg P kg−1, the effect of soil was not significant for the P fertilizer replacement value on a DM basis (PFRVDM). Soil had a significant effect on PFRV on a P uptake basis (PFRVP Uptake, P<0.001) and on an Olsen P basis (PFRVOlsen P, P<0.001) at this lowest vivianite rate. At the highest rate (100 mg P kg−1), PFRVDM, PFRVP Uptake, and PFRVOlsen P of vivianite were significantly affected by soil (P<0.05, 0.01 and 0.001, respectively) (Table S2 in the Supplement). In order to better understand the effect of soils on the different PFRV indices used, the relationships of these variables with soil properties were studied. These PFRV indices provide a relative comparison of efficiency with the mineral soluble P fertilizer.

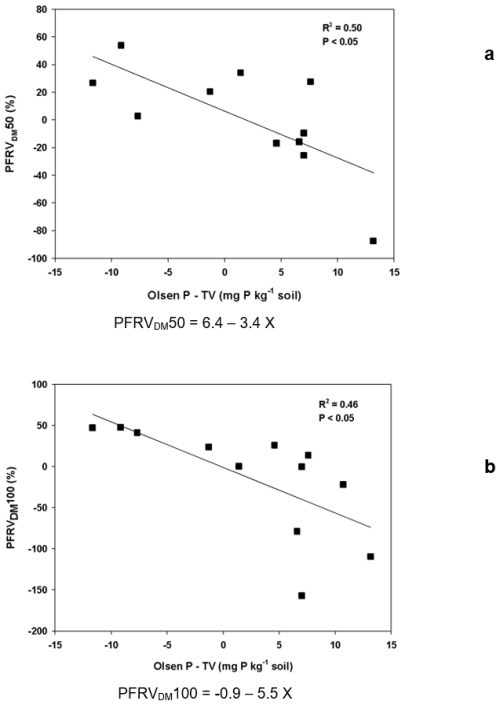

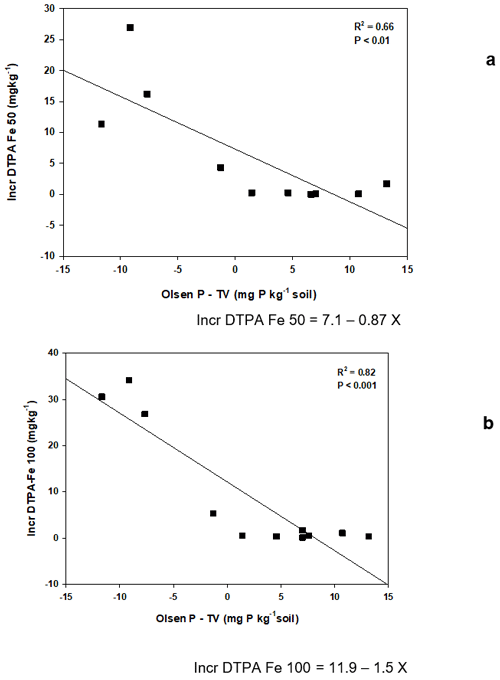

3.3 Phosphorus Fertilizer Replacement Value on a Dry Matter Basis

When soils were discriminated by carbonate content, differences in this index were not significant. Meanwhile, soils with pH lower than 6.6 showed PFRVDM at the highest P rate, significantly higher than those with pH>7.86 (Table 4). However, PFRVDM at both rates was not correlated with pH. It was negatively correlated with clay content (; P<0.01) and the value of the difference between soil Olsen P and its threshold value (Olsen P−TV; ; P<0.05) at the lowest P fertilizer rate (50 mg P kg−1) (in both cases an outlier with PFRVDM>540 was excluded), meanwhile it was negatively correlated only with Olsen P−TV (; P<0.05) at the highest P fertilizer rate (100 mg P kg−1). Thus, Olsen P−TV was the only variable that was correlated with PFRVDM at both P fertilizer rates, and PFRVDM decreased significantly with increased values of the difference (Olsen P−TV; Fig. 1). It was observed that for soils with Olsen P−TV less than 0 (which were also the soils with pH<6.6), PFRVDM was always positive at both P fertilizer rates, with average values of 26 % and 40 % at the lowest and the highest P fertilizer rates, respectively. However, for soils with Olsen P−TV higher than 0, most of the soils showed negative PFRVDM at the lowest P rate and three soils at the highest rate (Fig. 1). At the lowest P fertilizer rate, the soil with an Olsen P−TV of −9.2 resulted in a PFRVDM of 54 %. At the highest rate of P fertilizer application, soils with showed PFRVDM of around 50 % (Fig. 1).

Table 4Effect of soils on the mineral P fertilizer replacement value (PFRV) expressed in % estimated based on different approaches (DM yield. P uptake. Olsen P) and on the increase in the DTPA extractable Fe after crop harvest for both P fertilizer rates (50 and 100 mg P kg−1 soil).

Mean ± standard error

NS. not significant

The subindices for the P fertilizer replacement value abbreviation (PFRV) indicates: DM. on a dry matter basis. Puptake. on a P uptake basis. and Olsen P on a Olsen P after crop harvest basis.

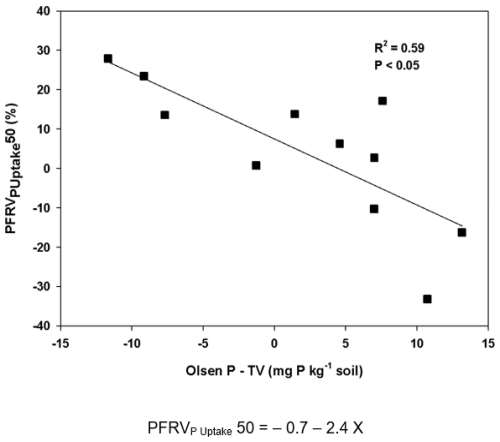

3.4 Phosphorus Fertilizer Replacement Value on a P Uptake Basis

The P fertilizer replacement value on a P uptake basis (PFRVP Uptake) was significantly affected by soil (Table S2). However, when soils were grouped by carbonate content or pH, the effect of soil type was not significant (Table 4). At the lowest P fertilizer rate, the relationship between PFRVP Uptake and soil properties was similar to that observed for PFRVDM: it was negatively correlated with clay content and Olsen P−TV ( and −0.77, respectively, P<0.01 in both cases; an outlier with excluded). The values of PFRVP Uptake for the lowest P fertilizer rate were in most cases above 0, with an average of 16 % for Olsen P−TV less than 0 and −18 % for Olsen P−TV higher than 0 (Fig. 2). At the highest P fertilizer rate, PFRVP Uptake was not related to any soil property, and its values ranged between −50 and 50, with an average of 11 % and −3 % for soils with Olsen P−TV less and higher than 0, respectively. When clay content and Olsen P−TV were considered in a multiple regression, both explained 53 % of the variance in PFRVP Uptake at the highest rate (; R2=0.53; P<0.05).

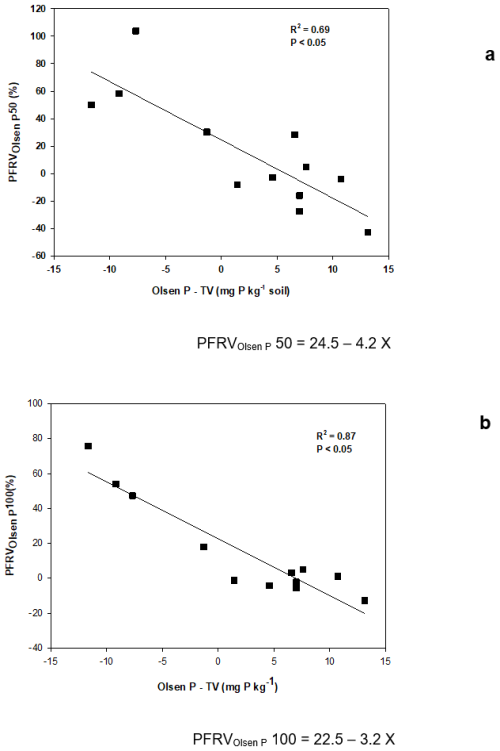

3.5 Phosphorus Fertilizer Replacement Value on an Olsen P Basis

The P fertilizer replacement value on an Olsen P basis (PFRVOlsen P) was also significantly affected by soil (Table S2). When soils were differentiated between calcareous and non-calcareous, differences in this index between both types of soil were not significant at both P fertilizer rates (Table 4). However, when discrimination was done on a pH basis, soils with pH<6.6 had significantly higher PFRVOlsen P than those with pH>7.86 at both P fertilizer rates (Table 4). The PFRVOlsen P at the lowest P fertilizer rate was negatively correlated with clay content (; P<0.01), pH (; P<0.01), and Olsen P−TV (; P<0.001). Correlations were similar for PFRVOlsen P at the highest P fertilizer rate: clay content (; P<0.05), pH (; P<0.001), and Olsen P−TV (; P<0.001). Overall, the highest correlation coefficients were observed for Olsen P−TV, which explained 69 % and 87 % of the variance at the lowest and the highest P fertilizer rate, respectively (Fig. 3). For Olsen P−TV less than 0, the average PFRVOlsen P for the lowest and the highest fertilizer rate was 61 % and 49 %, respectively; meanwhile, for Olsen P−TV higher than 0, it was −8.5 % and −2.1 %, respectively.

3.6 Increment in DTPA Extractable Fe

The effect of soil on the increment in DTPA extractable Fe with vivianite application relative to the control without fertilizer application was very significant (Table S2). While the increase was negligible in calcareous soils or in soil with pH>7.86, this increase was significant in non-calcareous soils or in soils with pH<6.6 (Table 4). The increase in DTPA extractable Fe was negatively correlated with pH, clay, and Olsen P−TV. At the lowest P rate, the correlation coefficients were −0.58 (P<0.05) for clay, −0.76 (P<0.01) for pH, and −0.81 (P<0.01) for Olsen P−TV. At the highest rate, correlation coefficients were −0.84 for pH and −0.9 for Olsen P−TV (P<0.001 in both cases). At both vivianite rates, DTPA extractable Fe was significantly increased at Olsen P−TV less than 0 (Fig. 4).

Although the effect of the mineral soluble fertilizer on DM yield, P uptake, and Olsen P outperformed that of vivianite, this product achieved a P fertilizer replacement value on a DM basis (PFRVDM) of around 50 % in some soils. This means that, in these soils, vivianite can replace half of the soluble mineral fertilizer, implying a promising result for its use as a P fertilizer. The assessment of the efficiency of vivianite relative to mineral fertilizer should be done based on the P fertilizer replacement value (PFRV) since soil properties differentially affect the fate of both soluble mineral fertilizer and vivianite. The PFRV estimated with the three approaches (DM, P uptake, and Olsen P) ranged widely among soils. This reveals a different effect of soil properties on the dynamics and, consequently, on the efficiency of both types of fertilizers. In particular, the best results of vivianite on PFRVDM were obtained in the four soils with acidic pH (<6.6) and in two calcareous soils (Soil 3 and 4) (Table S2). The highest increase of DTPA Fe with vivianite relative to control and mineral soluble fertilizer was observed in three acidic soils. This reveals that conditions prone to vivianite dissolution, i.e., acidic pH in soils, determine its efficiency as a P and Fe fertilizer.

Overall, results were lower when the PFRV was estimated on a P uptake basis, and only values above 20 % were found in two soils at the lowest P fertilizer rate (Fig. 2). Lower PFRV values on a P uptake basis can be expected since, with the P rates applied, particularly the highest P rate, a luxury consumption can be promoted, i.e., P accumulation in plants exceeding the minimal for maximum DM yield (Penn et al., 2022). On the other hand, negative values are expected when the P supply capacity of soils is high enough to cover crop needs, and this explains that, frequently, PFRV values were negative when Olsen P−TV was higher than 0 (soil P test above the threshold value), that is, when soil P is expected to cover crop needs. An increase in Olsen P above the P threshold value did not result in a further increase in crop yield (Johnston, 2001, 2005; Tandy et al., 2021). This could partly explain why soils with an already high P status in the current study did not lead to an increased PFRV.

An analysis of the PFRV on an Olsen P basis allows one to think that results could even be more positive with the application of vivianite as P fertilizer since average values were 49 % and 61 % at the highest and lowest P rate, respectively, when the soil Olsen P was below the threshold value which corresponded with soils with pH lower than 6.6 (Table 4). This is much higher than PFRV on a DM or P uptake basis and reveals that the long-term effect of vivianite, beyond the studied crop cycle, could be very interesting in acidic soils with P levels below the threshold value. Thus, one short-term growing cycle probably does not fully reflect the potential of vivianite as a P fertilizer, which can have a relevant residual effect according to the effect on the soil P test in soils with low P status.

It can be supposed that the PFRV of vivianite was determined by its solubility, with a crop response above the threshold values not being expected. However, the values of the PFRV on an Olsen P basis reveal that there is limited solubilization when the soil Olsen P value is above the threshold value (PFRVOlsen P around 0). Theoretically, for soluble fertilizers such as superphosphate, solubilization is not necessarily limited in soils with Olsen P above the threshold value. These results with Olsen P after harvesting agree with the observed increase in DTPA extractable Fe. This increased DTPA extractable Fe comes from the dissolution of vivianite (de Santiago and Delgado, 2010). This increase was negligible when the soil Olsen P was above the threshold value. Thus, it seems that fertilizer dissolution determined the response of crops to applied vivianite, and this dissolution was expected to be increased at acidic pH (pH<6.6), which corresponded to soils with Olsen P values below the threshold value for fertilizer response. In fact, the highest PFRV on Olsen P basis (around 100 %) was found in the more acidic soil. Metz et al. (2023) found that the dissolution rate of vivianite under anoxic conditions increased strongly with a decreasing pH, and at pH 5, all solid materials of vivianite were found to have completely dissolved. This observation was similar when a vivianite dissolution experiment was conducted under oxic conditions (personal communication with Rouven Metz). This could invariably mean that an acidic pH favours the dissolution of vivianite, leading to the release of P from vivianite, thereby making P available in the soil solution where plants can take up P. This situation seems to be different in alkaline soils (the other eight soils with pH≥7.86) because of a lower rate of dissolution (Metz et al., 2023).

However, pH should not be the only factor affecting P recovery from vivianite. In fact, soil 4 was calcareous and showed a PFRVDM of 34 % at the lowest fertilizer rate. This was also the only calcareous soil in which vivianite at both rates increased DM yield relative to control (Table S1). In addition, PFRV on a DM and P uptake basis was related to Olsen P−TV but not to pH. Thus, it seems that soil pH may have a crucial role in the dissolution of vivianite, as mentioned above, but there are other factors contributing to its use as fertilizer by crops, in particular, the available P status of soil (reflected in the Olsen P−TV values). This difference between Olsen P and threshold value explained more variance in the PFRV on DM and P uptake basis than pH. In any case, it is not easy to separate the effect of soil pH from that of low P availability since pH and Olsen P−TV were positively correlated.

In P-limiting soils, mechanisms to obtain adequate P for growth are triggered (Raghothama and Karthikeyan, 2005; Balemi and Negisho, 2012). This involves the modification of the plant root system (Lynch, 2011; López-Arredondo et al., 2014) and the increased exudation of organic acids (Neumann and Römheld, 1999; Dechassa and Schenk, 2004), which promotes the mobilization of poorly soluble P from soil (Kpomblekou-A and Tabatabai, 2003; Johnson and Loeppert, 2006). According to Schütze et al. (2020), organic ligands released by roots, such as citrate, enhance the dissolution of vivianite. Talboys et al. (2016) observed an increased organic acid concentration in the rhizosphere when struvite, a poorly soluble P compound, was supplied as a P fertilizer instead of soluble fertilizers. Thus, when a poorly soluble fertilizer such as vivianite is applied, an increased expression of P mobilizing mechanisms in P-poor soils can be expected. This contributes to explaining the increase in PFRV with decreased Olsen P−TV values.

The role of soil microorganisms in the rhizosphere in promoting the dissolution and use of P from vivianite by crops cannot be ruled out. They play an important role in the solubilization and mobilization of P (Richardson, 2007; García-López et al., 2018, 2021), thus increasing the bioavailability of P (Deubel and Merbach, 2005), especially in P-poor soils. In P-deficient soils, microbial communities are often dominated by phosphate-solubilizing bacteria and fungi, capable of producing organic acids and enzymes that solubilize P, thus making it available for plant uptake (Weigh et al., 2023). This is not always the case under P-abundant conditions (Sun et al., 2022b; Yadav and Yadav, 2024). Thus, the particular structure of microbial communities in P-deficient soils can contribute to better dissolution of vivianite and, consequently, to its efficiency as a P fertilizer.

The negative correlation observed between replacement values and clay content in some cases can be determined by the correlation between this soil property and the Olsen P−TV values. In addition, the soils with pH above neutrality had the highest clay content. Furthermore, clay is a soil property usually positively correlated with P buffer capacity and P adsorption, thus affecting P dynamics and availability to plants (Recena et al., 2015, 2016).

In the current study, the DTPA extractable Fe supports the increased dissolution of vivianite under acidic conditions, which were also the soils with the lowest P availability to plants. Vivianite has a considerable content of Fe (Eynard et al., 1992), and the release of Fe is expected following its dissolution. However, at alkaline pH, there is a preferential release of P over Fe leading to the structural oxidation of Fe and the subsequent formation of a Fe(III)-bearing phosphate phase (Thinnappan et al., 2008). In fact, the efficiency of synthetic vivianite as a source of Fe for plants in calcareous soils (Rombolà et al., 2003; Díaz et al., 2009), has been ascribed to the formation of poorly crystalline oxides such as ferrihydrite and lepidocrocite (Eynard et al., 1992; Roldán et al., 2002). These oxides have a high specific surface and high P adsorption capacity. Thus, reaction products of vivianite dissolution in alkaline soils can contribute to a decreased PFRV in these soils.

The results obtained are promising with a view of using vivianite from water purification treatments as P fertilizer. Its efficiency as fertilizer was in line with other fertilizers obtained from recycling (Hernández-Mora et al., 2024; Frick et al., 2025). However, this efficiency varies greatly depending on soil properties and reveals the need of tailoring its use to specific soil conditions. Although further field research is necessary for more solid recommendations, based on the present results, it seems to be a recommendable fertilizer in acidic P-poor soils. Even in non-acidic P-poor soils, it can have positive effects as a P fertilizer. An advantage is that its dissolution seems to be enhanced by plants and microbial P-mobilizing mechanisms that are triggered in P-poor soils when poorly soluble fertilizers are applied. This means that its dissolution is faster when plants are present, thus reducing environmental risks when soils have a low P adsorption capacity. Since it is a poorly soluble product, vivianite should be incorporated into the soil close to the areas of maximum root development to enhance its solubilization and use by plants, as previously done for recommendation as Fe fertilizer (Rosado et al., 2002; Díaz et al., 2009). However, in the EU, for its practical use and recommendation, a normative change is necessary to avoid restrictions on the use of products with high Fe content. From an economic point of view, P recovery from wastewater through vivianite precipitation is gaining interest since its separation is easier than other byproducts, such as struvite, through its magnetic properties, and this can contribute to a more competitive price as a fertilizer.

Overall, vivianite was not as efficient as P fertilizer as a soluble mineral fertilizer. The application of vivianite as a P fertilizer was more effective in acidic soils with soil P tests below the threshold value for fertilizer response. The effect of vivianite on dry matter yield could be equivalent, on average, to 40 % of the same amount applied as mineral soluble fertilizer in these soils. The effect on Olsen P in soil could be equivalent, on average, to 61 % of the same amount applied as soluble mineral fertilizer. This is explained not only by the increased solubility of this fertilizer under acidic conditions but also by a low P availability to plants, which can trigger plant and microbial mobilization mechanisms, leading to increased efficiency of vivianite as a P fertilizer. These results are encouraging for promoting the use of vivianite from wastewater treatment as a P fertilizer, the application of which should be adapted to the soil properties, and is especially recommended for acidic soils low in P.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-11-975-2025-supplement.

Conceptualization, TA, RR and AD; data curation, TA; formal analysis, TA, JMQ and AD; investigation, TA, RR, JMQ, AMG-L and AD; methodology, TA, RR and AMG-L; supervision, AD and MCdC; writing – original draft, TA, MCdC and AD; writing – review and editing, TA, AMG-L, MCdC and AD. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

The authors would like to appreciate Wetsus (a non-academic partner – NAPO) of the P-TRAP project for providing the vivianite from water purification used in this study. Our sincere gratitude also goes to Vidal Barrón for assisting with the characterization of the fertilizer product used in the study. We would also like to thank Prof. Dr Erik Smolders for the opportunity to carry out some of the laboratory analysis at his laboratory during a 3 month secondment at KU Leuven in Belgium.

This research was funded by the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innvation Programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 813438 and is a part of the P-TRAP (Diffuse phosphorus input to surface waters – new concepts in removal, recycling, and management) Project.

This paper was edited by Ping He and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Ayeyemi, T., Recena, R., García-López, A. M., and Delgado, A.: Circular Economy Approach to Enhance Soil Fertility Based on Recovering Phosphorus from Wastewater, Agronomy, 13, 1513, https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13061513, 2023.

Ayeyemi, T., Recena, R., García-López, A. M., Quintero, J. M., del Campillo, M. C., and Delgado, A.: Efficiency of Vivianite from Water Purification Depending on Its Mixing with Superphosphate and Application Method, Agronomy, 14, 2639, https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14112639, 2024.

Balemi, T. and Negisho, K.: Management of soil phosphorus and plant adaptation mechanisms to phosphorus stress for sustainable crop production: a review, J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr., https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-95162012005000015, 2012.

Bibi, S., Irshad, M., Ullah, F., Mahmood, Q., Shahzad, M., Tariq, M. A. U. R., Hussain, Z., Mohiuddin, M., An, P., Ng, A. W. M., Abbasi, A., Hina, A., and Gonzalez, N. C. T.: Phosphorus extractability in relation to soil properties in different fields of fruit orchards under similar ecological conditions of Pakistan, Front. Ecol. Evol., 10, 1077270, https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2022.1077270, 2023.

Bindraban, P. S., Dimkpa, C., Nagarajan, L., Roy, A., and Rabbinge, R.: Revisiting fertilisers and fertilisation strategies for improved nutrient uptake by plants, Biol. Fertil. Soils, 51, 897–911, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-015-1039-7, 2015.

Bueis, T., Bravo, F., Pando, V., Kissi, Y.-A., and Turrión, M.-B.: Phosphorus availability in relation to soil properties and forest productivity in Pinus sylvestris L. plantations, Annals of Forest Science, 76, 97, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-019-0882-3, 2019.

Cordell, D., Drangert, J.-O., and White, S.: The story of phosphorus: Global food security and food for thought, Global Environmental Change, 19, 292–305, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.10.009, 2009.

De Santiago, A. and Delgado, A.: Interaction between beet vinasse and iron fertilisers in the prevention of iron deficiency in lupins, J. Sci. Food Agric., 90, 2188–2194, https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.4068, 2010.

Dechassa, N. and Schenk, M. K.: Exudation of organic anions by roots of cabbage, carrot, and potato as influenced by environmental factors and plant age, Z. Pflanzenernähr. Bodenk., 167, 623–629, https://doi.org/10.1002/jpln.200420424, 2004.

Delgado, A. and Gómez, J. A.: The Soil. Physical, Chemical and Biological Properties, in: Principles of Agronomy for Sustainable Agriculture, edited by: Villalobos, F. J. and Fereres, E., Springer International Publishing, Cham, 15–26, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-46116-8_2, 2016.

Delgado, A. and Scalenghe, R.: Aspects of phosphorus transfer from soils in Europe, J. Plant Nutr. Soil. Sci., 171, 552–575. 2008.

Deinert, L., Ashekuzzaman, S. M., Forrestal, P., and Schmalenberger, A.: One-time application of struvites, ashes and superphosphate had no major impact on the microbial phosphorus mobilization capabilities over 15 months in a grassland field trial, Applied Soil Ecology, 212, 106198, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2025.106198, 2025.

Deubel, A. and Merbach, W.: Influence of Microorganisms on Phosphorus Bioavailability in Soils, in: Microorganisms in Soils: Roles in Genesis and Functions, edited by: Varma, A. and Buscot, F., Soil Biology, vol. 3, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-26609-7_9, 2005.

Díaz, I., Barrón, V., Del Campillo, M. C., and Torrent, J.: Vivianite (ferrous phosphate) alleviates iron chlorosis in grapevine, Vitis, 48, 107–113, 2009.

Dijkstra, N., Slomp, C. P., and Behrends, T.: Vivianite is a key sink for phosphorus in sediments of the Landsort Deep, an intermittently anoxic deep basin in the Baltic Sea, Chemical Geology, 438, 58–72, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2016.05.025, 2016.

Egger, M., Jilbert, T., Behrends, T., Rivard, C., and Slomp, C. P.: Vivianite is a major sink for phosphorus in methanogenic coastal surface sediments, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 169, 217–235, 2015.

Eshun, L. E., García-López, A. M., Recena, R., Coker, V., Shaw, S., Lloyd, J., and Delgado, A.: Assessing microbially mediated vivianite as a novel phosphorus and iron fertilizer, Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric., 11, 47, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40538-024-00558-0, 2024.

Eynard, A., Del Campillo, M. C., Barron, V., and Torrent, J.: Use of vivianite (Fe3(PO4)2.8H20) to prevent iron chlorosis in calcareous soils, Fertilizer Research, 31, 61–67, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01064228, 1992.

Faller, L., Kowalchuk, G. A., and Kuramae, E. E.: Phosphate-cycling activity of the soil microbiome in response to the recycled phosphates struvite and vivianite, Applied Soil Ecology, 213, 106296, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2025.106296, 2025.

Fodoué, Y., Nguetnkam, J. P., Tchameni, R., Basga, S. D., and Penaye, J.: Assessment of the fertilizing effect of vivianite on the growth and yield of the bean “Phaseolus vulgaris” on oxisoils from Ngaoundere (central north Cameroon), Int. Res. J. Earth Sci., 3, 18–26, 2015.

Frick, H., Bünemann, E. K., Hernandez-Mora, A., Eigner, H., Geyer, S., Duboc, O., and Ylivainio, K.: Bio-based fertilisers can replace conventional inorganic P fertilisers under European pedoclimatic conditions, Field Crops Research, 325, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2025.109803, 2025.

Gee, G. W. and Bauder, J. W.: Particle-Size Analysis, in: Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 1. Physical and Mineralogical Methods, Agronomy Monograph No. 9, 2nd edn., edited by: Klute, A., American Society of Agronomy/Soil Science Society of America, Madison, WI, 383–411, https://doi.org/10.2136/sssabookser5.1.2ed.c15, 1986.

García-López, A. M., Avilés, M. and Delgado, A.: Effect of various microorganisms on phosphorus uptake from insoluble Ca-phosphates by cucumber plants, J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci., 179, 454–465, https://doi.org/10.1002/jpln.201500024, 2016.

García-López, A. M., Recena, R., Avilés, M. and Delgado. A.: Effect of Bacillus subtilis QST713 and Trichoderma asperellum T34 on P uptake by wheat and how it is modulated by soil properties, J. Soils Sediments, 18, 727–738, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-017-1829-7, 2018.

García-López, A. M., Recena, R. and Delgado, A.: The adsorbent capacity of growing media does not constrain myo-inositol hexakiphosphate hydrolysis but its use as a phosphorus source by plants, Plant Soil, 459, 277–288, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-020-04764-1, 2021.

García-López, A. M., Recena, R., Quintero, J. M., and Delgado, A.: Phytate efficiency as a phosphorus source for wheat varies with soil properties, Geoderma, 457, 117291, 2025.

Heckenmüller, M., Narita, D., and Klepper, G.: Global availability of phosphorus and its implications for global food supply: An Economic Overview, Kiel Working Paper, (1897), 1–26, 2014.

Heiberg, L., Koch, C. B., Kjaergaard, C., Jensen, H. S., and Hansen, H. C. B.: Vivianite precipitation and phosphate sorption following iron reduction in anoxic soils, Journal of Environmental Quality, 41, 938–949, 2012.

Hernandez-Mora, A., Duboc, O., Lombi, E., Bünemann, E. K., Ylivainio, K., Symanczik, S., Delgado, A., Abu Zahra, N., Nikama, J., Zuin, L., Doolette, C.L., Eigner, H. and Santner, J.: Fertilization efficiency of thirty marketed and experimental recycled phosphorus fertilizers, Journal of Cleaner Production, 467, 142957, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.142957, 2024.

Hijbeek, R., Ten Berge, H. F. M., Whitmore, A. P., Barkusky, D., Schröder, J. J., and Van Ittersum, M. K.: Nitrogen fertiliser replacement values for organic amendments appear to increase with N application rates, Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst., 110, 105–115, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10705-017-9875-5, 2018.

Jiang, Y., Zhang, Y. G., Zhou, D., Qin, Y., and Liang, W. J.: Profile distribution of micronutrients in an aquic brown soil as affected by land use, Plant Soil Environ., 55, 468–476, https://doi.org/10.17221/57/2009-PSE, 2009.

Johnson, S. E. and Loeppert, R. H.: Role of Organic Acids in Phosphate Mobilization from Iron Oxide, Soil Science Soc. of Amer. J., 70, 222–234, https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2005.0012, 2006.

Johnston, A. E.: Principles of crop nutrition for sustainable food production, Proceedings of the International Fertiliser Society, 459, 39, 2001.

Johnston, A. E.: Phosphate nutrition of arable crops, in: Phosphorus: agriculture and the environment, Agronomy Series (46), edited by: Sims, J. T. and Sharpley, A. N., Madison, USA, ASA, CSSA, SSSA, 495–519, https://doi.org/10.2134/agronmonogr46.c15, 2005.

Jowett, C., Solntseva, I., Wu, L., James, C., and Glasauer, S.: Removal of sewage phosphorus by adsorption and mineral precipitation, with recovery as a fertilizing soil amendment, Water Sci. Technol., 77, 1967–1978, https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2018.027, 2018.

Keyzer, M.: Towards a Closed Phosphorus Cycle, De Economist, 158, 411–425, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-010-9150-5, 2010.

Kpomblekou-A, K. and Tabatabai, M. A.: Effect of low-molecular weight organic acids on phosphorus release and phytoavailabilty of phosphorus in phosphate rocks added to soils, Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 100, 275–284, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-8809(03)00185-3, 2003.

Lindsay, W. L. and Norvell, W. A.: Development of a DTPA Soil Test for Zinc, Iron, Manganese, and Copper, Soil Science Society of America Journal, 42, 421–428, 1978.

Liu, L., Gao, Y., Yang, W., Liu, J. and Wang, Z. : Community metagenomics reveals the processes of nutrient cycling regulated by microbial functions in soils with P fertilizer input, Plant Soil, 499, 139–154, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-023-05875-1, 2024.

López-Arredondo, D. L., Leyva-González, M. A., González-Morales, S. I., López-Bucio, J., and Herrera-Estrella, L.: Phosphate Nutrition: Improving Low-Phosphate Tolerance in Crops, Annu. Rev. Plant Biol., 65, 95–123, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-035949, 2014.

Lynch, J. P.: Root Phenes for Enhanced Soil Exploration and Phosphorus Acquisition: Tools for Future Crops, Plant Physiology, 156, 1041–1049, https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.111.175414, 2011.

Mahdi, C. H. H. and Uygur, V.: Effect some soil properties (organic matter, soil texture, lime) on the geochemical phosphorus fractions, Bionatura, 3, https://doi.org/10.21931/RB/2018.03.04.7, 2018.

Metz, R., Kumar, N., Schenkeveld, W. D. C., and Kraemer, S. M.: Rates and Mechanism of Vivianite Dissolution under Anoxic Conditions, Environ. Sci. Technol., 57, 17266–17277, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.3c04474, 2023.

Monreal, C., Derosa, M., Mallubhotla, S. C., Bindraban, P. S. and Dimkpa, C.: Nanotechnologies for increasing the crop use efficiency of fertilizer-micronutrients, Biol. Fertil. Soils, 52, 423–437, 2016.

Murphy, J. A. and Riley, J. P. A.: A Modified Single Solution Method for the Determination of Phosphate in Natural Waters, Analytica Chimica Act., 27, 31–36, 1962.

Muys, M., Phukan, R., Brader, G., Samad, A., Moretti, M., Haiden, B., Pluchon, S., Roest, K., Vlaeminck, S. E. and Spiller, M. A.: Systematic comparison of commercially produced struvite: Quantities, qualities and soil-maize phosphorus availability, Science of the Total Environment, 756, 143726, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143726, 2021.

Nanzyo, M., Onodera, H., Hasegawa, E., Ito, K., and Kanno, H.: Formation and dissolution of vivianite in paddy field soil, Soil Science Society of America Journal, 77, 1452–1459, 2013.

Neumann, G. and Römheld, V.: Root excretion of carboxylic acids and protons in phosphorus-deficient plants, Plant and Soil, 211, 121–130, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004380832118, 1999.

Olaniyan, J. O., Ogunkunle A. O., and Aduloju, M. O.: Response of soil types to fertilizer application as conditioned by precipitation in the Southern Guinea Savanna Ecology of Nigeria, Proceedings of the International Soil Tillage Research Organisation (ISTRO) Symposium), 419–428, 2011.

Or, D., Smets, B. F., Wraith, J. M., Dechesne, A. and Friedman, S. P: Physical constraints affecting bacterial habitats and activity in unsaturated porous media – a review, Adv. Water Resour., 30, 1505–1527, 2007.

Penn, C. J., Camberato, J. J. and Wiethorn, M. A.: How Much Phosphorus Uptake Is Required for Achieving Maximum Maize Grain Yield? Part 1: Luxury Consumption and Implications for Yield, Agronomy, 13, 95, https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13010095, 2022.

Peth, S., Horn, R., Beckmann, F., Donath, T., Fischer, J. and Smucker, A. J. M.: Three-dimensional quantification of intraaggregate pore-space features using synchrotron-radiation-based microtomography, Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 72, 897–907, https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2007.0130, 2008.

Pizzeghello, D., Berti, A., Nardi, S., and Morari, F.: Relationship between soil test phosphorus and phosphorus release to solution in three soils after long-term mineral and manure application, Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 233, 214–223, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2016.09.015, 2016.

Raghothama, K. G. and Karthikeyan, A. S.: Phosphate Acquisition, Plant Soil, 274, 37–49, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-004-2005-6, 2005.

Recena, R., Torrent, J., del Campillo, M. C. and Delgado, A.: Accuracy of Olsen P to assess plant P uptake in relation to soil properties and P forms. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 35, 4, 1571–1579, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-015-0332-z, 2015.

Recena, R., Díaz, I., Del Campillo, M. C., Torrent, J., and Delgado, A.: Calculation of threshold Olsen P values for fertilizer response from soil properties, Agron. Sustain. Dev., 36, 54, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-016-0387-5, 2016.

Recena, R., Díaz, I., and Delgado, A.: Estimation of total plant available phosphorus in representative soils from Mediterranean areas, Geoderma, 297, 10–18, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2017.02.016, 2017.

Recena, R., Cade-Menun, B. J., and Delgado, A.: Organic Phosphorus Forms in Agricultural Soils under Mediterranean Climate, Soil Science Society of America Journal, 82, 783–795, https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2017.10.0360, 2018.

Recena, R., García-López, A. M., Quintero, J. M., Skyttä, A., Ylivainio, K., Santner, J., Buenemann, E., and Delgado, A.: Assessing the phosphorus demand in European agricultural soils based on the Olsen method, Journal of Cleaner Production, 379, 134749, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134749, 2022.

Richardson, A. E.: Making microorganisms mobilize soil phosphorus, in: First International Meeting on Microbial Phosphate Solubilization, vol. 102, edited by: Velázquez, E. and Rodríguez-Barrueco, C., Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 85–90, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-5765-6_10, 2007.

Roldán, R., Barrón, V., and Torrent, J.: Experimental alteration of vivianite to lepidocrocite in a calcareous medium, Clay miner., 37, 709–718, https://doi.org/10.1180/0009855023740072, 2002.

Rombolà, A. D., Toselli, M., Carpintero, J., Ammari, T., Quartieri, M., Torrent, J.and Marangoni, B.: Prevention of iron-deficiency induced chlorosis in kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa) through soil application of synthetic vivianite in a calcareous soil, Journal of Plant Nutrition, 26, 2031–2041, https://doi.org/10.1081/PLN-120024262, 2003.

Rosado, R., Del Campillo, M. C., Martínez, M. A., Barrón, V., and Torrent, J.: [No title found], Plant and Soil, 241, 139–144, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016058713291, 2002.

Rothe, M., Frederichs, T., Eder, M., Kleeberg, A. and Hupfer, M.: Evidence for vivianite formation and its contribution to long-term phosphorus retention in a recent lake sediment: A novel analytical approach, Biogeosciences, 11, 5169–5180, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-11-5169-2014, 2014.

Schröder, J. J., Cordell, D., Smit, A. L., and Rosemarin, A.: Sustainable Use of Phosphorus. Wageningen University and Research Centre, Stockholm Environment Institute, Report 357, 2010.

Schütze, E., Gypser, S., and Freese, D.: Kinetics of Phosphorus Release from Vivianite, Hydroxyapatite, and Bone Char Influenced by Organic and Inorganic Compounds, Soil Systems, 4, 15, https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems4010015, 2020.

Sharma, S. B., Sayyed, R. Z., Trivedi, M. H., and Gobi, T. A.: Phosphate solubilizing microbes: sustainable approach for managing phosphorus deficiency in agricultural soils, SpringerPlus, 2, 587, https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-2-587, 2013.

Soil Survey Staff: Keys to Soil Taxonomy, 12th Edition, USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, Washington DC., 2014.

Soo, A. and Shon, H. K.: A nutrient circular economy framework for wastewater treatment plants, Desalination, 592, 118090, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2024.118090, 2024.

StatPoint Technologies: Statgraphics Centurion 18, StatPoint Technologies [software], https://www.statgraphics.com/centurion-xviii (last access: 21 November 2025), 2017.

Strong, D. T., Wever, H. D., Merckx, R. and Recous, S.: Spatial location of carbon decomposition in the soil pore system, Eur. J. Soil Sci., 55, 739–750, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2389.2004.00639.x, 2004.

Sumner, M. E. and Miller, W. P.: Cation Exchange Capacity and Exchange Coefficients, in: Methods of Soil Analysis Part 3: Chemical Methods, SSSA Book Series 5, edited by: Sparks, D. L., Soil Science Society of America, Madison, Wisconsin, 1201–1230, 1996.

Sun, T., Fei, K., Deng, L., Zhang, L., Fan, X., and Wu, Y.: Adsorption-desorption kinetics and phosphorus loss standard curve in erosive weathered granite soil: Stirred flow chamber experiments, Journal of Cleaner Production, 347, 131202, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131202, 2022a.

Sun, R., Zhang, W., Liu, Y., Yun, W., Luo, B., Chai, R., Zhang, C., Xiang, X., and Su, X.: Changes in phosphorus mobilization and community assembly of bacterial and fungal communities in rice rhizosphere under phosphate deficiency, Front. Microbiol., 13, 953340, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.953340, 2022b.

Syers, J. K., Johnston, A. E. and Curtin, D.: Efficiency of soil and fertilizer phosphorus use: reconciling changing concepts of soil phosphorus behaviour with agronomic information (FAO Fertilizer and Plant Nutrition Bulletin 18), Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome, Italy, 2008.

Talboys, P. J., Heppell, J., Roose, T., Healey, J. R., Jones, D. L., and Withers, P. J. A.: Struvite: a slow-release fertiliser for sustainable phosphorus management?, Plant Soil, 401, 109–123, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-015-2747-3, 2016.

Tandy, S., Hawkins, J. M., Dunham, S. J., Hernandez-Allica, J., Granger, S. J., Yuan, H., McGrath, S.P. and Blackwell, M. S.: Investigation of the soil properties that affect Olsen P critical values in different soil types and impact on P fertiliser recommendations, European Journal of Soil Science, 72, 1802–1816, https://doi.org/10.1111/ejss.13082, 2021.

The Economist: A huge Norwegian phosphate rock find is a boon for Europe, https://www.economist.com/europe/2023/06/08/a-huge-norwegian-phosphate-rock-find-is-a-boon-for-europe (last access: 20 May 2024), 2023.

Thinnappan, V., Merrifield, C. M., Islam, F. S., Polya, D. A., Wincott, P., and Wogelius, R. A.: A combined experimental study of vivianite and As (V) reactivity in the pH range 2–11, Applied Geochemistry, 23, 3187–3204, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2008.07.001, 2008.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision, Key Findings and Advance Tables, Working Paper no. ESA/P/WP/248, 2017.

Walkley, A. J. and Black, I. A.: Estimation of soil organic carbon by the chromic acid titration method, Soil Sci., 37, 29–38, https://doi.org/10.1097/00010694-193401000-00003, 1934.

Weigh, K. V., Batista, B. D., Hoang, H., and Dennis, P. G.: Characterisation of Soil Bacterial Communities That Exhibit Chemotaxis to Root Exudates from Phosphorus-Limited Plants, Microorganisms, 11, 2984, https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11122984, 2023.

Wilfert, P., Dugulan, A. I., Goubitz, K., Korving, L., Witkamp, G. J., and Van Loosdrecht, M. C. M.: Vivianite as the main phosphate mineral in digested sewage sludge and its role for phosphate recovery, Water Research, 144, 312–321, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2018.07.020, 2018.

Withers, P. J., Elser, J. J., Hilton, J., Ohtake, H., Schipper, W. J., and Van Dijk, K. C.: Greening the global phosphorus cycle: how green chemistry can help achieve planetary P sustainability, Green Chemistry, 17, 2087–2099, 2015.

Wu, Y., Luo, J., Zhang, Q., Aleem, M., Fang, F., Xue, Z., and Cao, J.: Potentials and challenges of phosphorus recovery as vivianite from wastewater: A review, Chemosphere, 226, 246–258, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.03.138, 2019.

Xie, J., Zhuge, X., Liu, X., Zhang, Q., Liu, Y., Sun, P., Zhao, Y. and and Tong, Y.: Environmental sustainability opportunity and socio-economic cost analyses of phosphorus recovery from sewage sludge, Environmental Science and Ecotechnology, 16, 100258, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ese.2023.100258, 2023.

Yadav, A. and Yadav, K.: Regulation of Plant-Microbe Interactions in the Rhizosphere for Plant Growth and Metabolism: Role of Soil Phosphorus, in: Phosphorus in Soils and Plants, edited by: A. Anjum, N., Masood, A., Umar, S., and A. Khan, N., IntechOpen, https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.112572, 2024.

Yang, S., Yang, X., Zhang, C., Deng, S., Zhang, X., Zhang, Y., and Cheng, X.: Significantly enhanced P release from vivianite as a fertilizer in rhizospheric soil: Effects of citrate, Environ. Res., 113567, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.113567, 2022.

Zhang, Y., Huang, S., Guo, D., Zhang, S., Song, X., Yue, K., Zhang, K., and Bao, D.: Phosphorus adsorption and desorption characteristics of different textural fluvo-aquic soils under long-term fertilization, J. Soils Sediments, 19, 1306–1318, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-018-2122-0, 2019.