the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Living cover crops alter the fate of pesticide residues in soil: influence of pesticide physicochemical properties

Noé Vandevoorde

Igor Turine

Alodie Blondel

Yannick Agnan

Living cover crops play a key role in reducing nitrogen leaching to groundwater during fallow periods. They also enhance soil microbial activity through root exudates, improving soil structure and increasing organic matter content. While the degradation of pesticides in soil relies primarily on microbial biodegradation, the extent to which cover crops influence this degradation remains poorly quantified. The objective of this study was to evaluate to what extent pesticide residues with contrasting physicochemical properties are affected by living cover crops. We conducted a greenhouse experiment testing two cover crop densities against a bare soil control, and quantified residues (by LC-QTOFMS) of 18 pesticide ingredients (active substances and safeners) in both soil and soil solution. We then related the observed reduction in residues to key physicochemical properties of the pesticide ingredients. Our results show that thin cover crops (0.4 tDM ha−1) reduce pesticide leaching 80 d after sowing relative to bare soil, retaining residues in the topsoil. Moreover, well-developed cover crops (1 tDM ha−1) reduce soil pesticide residues by more than 33 % for compounds with low to high water solubility (s⩽1400 mg L−1) and low to moderate soil mobility (Koc⩾160 mL g−1). This effect is likely due to enhanced pesticide degradation of the retained pesticide in the rhizosphere. These findings confirm previous studies focused on individual compounds, individual cover crop types or individual soil compartments, while providing new thresholds for physicochemical properties associated with significant pesticide degradation. By directly enhancing pesticide degradation within the soil compartment where pesticides are applied, cover crops limit their transfer to other environmental compartments, particularly groundwater.

- Article

(1991 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(2751 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Pesticides play a major role in modern agriculture, helping to stabilise crop yields, optimise farm labour and support overall agricultural production (Cooper and Dobson, 2007; Oerke, 2006). However, their use is associated with multiple – and well-documented – negative impacts on the environment and human health (Damalas and Koutroubas, 2016; Kim et al., 2017; Mandal et al., 2020; Stoate et al., 2001). Among these, the widespread contamination of ecosystems and consequent degradation of ecosystem services (Leenhardt et al., 2023; Power, 2010; Silva et al., 2019) directly affects the quality of drinking water supplies (Joerss et al., 2024; Pedersen et al., 2016; Syafrudin et al., 2021), poses risks to general human health (Gerken et al., 2024; Rani et al., 2021; Scorza et al., 2023; Shekhar et al., 2024) and results in significant social costs (Alliot et al., 2022; Bourguet and Guillemaud, 2016).

Pesticides applied to plants and agricultural soils undergo various environmental fates depending on their physicochemical properties: (1) they may be degraded by photolysis, hydrolysis, abiotic oxidation or biodegradation into a range of degradation products; (2) they may be bound to soil minerals and organic matter or be absorbed by plant roots; or (3) they may be transferred off-site by volatilisation, run-off, erosion or leaching to groundwater bodies. While these processes (aside from soil sorption) reduce pesticide content in agricultural soil, they contribute to diffuse contamination of other environmental compartments (Leenhardt et al., 2023). Like for nitrogen, the risk of pesticide leaching in temperate regions is highest in autumn and early winter, when increased precipitation, lower temperatures and slowed crop growth – inducing reduced evapotranspiration – promote aquifer recharge (Thorup-Kristensen et al., 2003). This issue is further exacerbated by the persistence of pesticide residues in soil long after application, sustaining diffuse contamination even after the pesticides have been banned (de Albuquerque et al., 2020; Sabatier et al., 2021). This underlines the need to explore strategies to limit the persistence and mobility of pesticides in topsoil as soon as possible after application and during aquifer recharge periods. Among these strategies, bio- and phyto-remediations offer a promising avenue.

Bioremediation transforms contaminants into non-toxic substances through the activity of soil microorganisms. Phytoremediation extends this process, encompassing plants and their rhizosphere (Cycoń et al., 2017; Eevers et al., 2017; Jia et al., 2023). This involves (1) rhizodegradation, rhizostabilisation and rhizofiltration which degrade, stabilise or concentrate contaminants near the roots, respectively, and (2) plant uptake and metabolism, aided by endophytic microorganisms. In particular, rhizofiltration is induced by soil water flux driven by the plant evapotranspiration (Tarla et al., 2020). Root exudates provide nutrients that stimulate microbial activity and promote synergistic interactions within rhizospheric microbial communities, enhancing the degradation of persistent compounds. In addition, plant and microbial enzymes co-degrade pesticides in the rhizosphere, with root dynamics improving soil aeration and facilitating oxidative degradation (Eevers et al., 2017; Jia et al., 2023; McGuinness and Dowling, 2009). Rhizoremediation can thus be considered as a biostimulation strategy in which plants stimulate native microbial communities via root exudates, amplifying bioremediation (Cycoń et al., 2017; Tarla et al., 2020). Phytoremediation approaches are particularly suited to mitigating diffuse pollution from cumulative agricultural applications, offering scalable, cost-effective solutions that stabilise and degrade pesticides while preventing their transfer to other environmental compartments (Eevers et al., 2017; McGuinness and Dowling, 2009; Tarla et al., 2020).

Originally introduced to reduce soil erosion and nitrate leaching (as catch crops), cover crops are closely related to the principles of phytoremediation. By maintaining a living plant cover during the fallow period when leaching risks are highest, they stimulate soil microbial activity and offer a practical way to integrate phytoremediation into annual agricultural cycles without taking land out of production. In addition to their biostimulative effects, cover crops induce physical, chemical and biological changes in the soil environment and contribute to ecosystem services such as nutrient cycling, water regulation or pest and disease suppression (Dabney et al., 2001; Hao et al., 2023; Justes and Richard, 2017; Reeves, 1994). These changes also influence pesticide dynamics, including mobility, retention and degradation within the soil. While the effects of established cover crops on newly applied pesticides have been studied (e.g. Cassigneul et al., 2015, 2016; Perkins et al., 2021; Whalen et al., 2020), research on the effects of newly sown cover crops on existing pesticide residues remains limited.

In this limited research, studies suggest several mechanisms by which cover crops can reduce pesticide transport, including increasing soil organic matter, biostimulation and improving soil structure. These processes contribute to greater pesticide adsorption, faster degradation and reduced leaching. For example, a one year field study by Bottomley et al. (1999) showed that winter rye (Secale cereale) enhanced subsurface microbial activity, thereby promoting the mineralisation of the herbicide 2,4-D. Similarly, multi-year field studies reported reductions in pesticide concentrations under cover crops compared to bare soil: Potter et al. (2007) observed decreases of up to 33 % for the herbicide atrazine in groundwater under sunn hemp (Crotalaria juncea), while White et al. (2009) reported reductions of up 41 % for the herbicide metolachlor. However, these studies focused on individual molecules, specific cover types and single soil compartment (soil or soil solution), limiting the generalisability of their results.

Long-term field experiments, such as those conducted by Alletto et al. (2012) and Agnan et al. (2019), have extended these studies by examining multiple factors influencing pesticide retention and mobility, in both soil and soil solution. Alletto et al.'s study (2012), conducted over four years, showed that cover crops such as oats (Avena sativa) could reduce losses of the herbicide isoxaflutole by 25 % to 50 % compared to bare soil. They highlighted the importance of soil organic matter and cover biomass production in reducing leaching: cover crops producing over 2 tDM ha−1 significantly reducing leaching, whereas no significant effect was observed at 0.3 tDM ha−1 (DM: dry matter). These results illustrate the potential of cover crops to improve soil properties, increasing the travel time of pesticides through biologically active soil layers and facilitating their degradation before reaching groundwater. Agnan et al. (2019) extended this research to 32 active substances and soil solution analyses. They identified organic matter content and evapotranspiration from cover crops as critical factors in the retention of pesticides in the biologically active layers. In addition, they observed a resurgence of certain molecules under fully developed cover crops, suggesting that evapotranspiration can bring back up substances that have started to leach down in the soil profile. This underlines the criticality of the transition between (cash) crop and cover crop periods, when reduced evapotranspiration can lead to increased leaching before the cover crop has had time to take full effect. Although five different cover crop mixes were grown, data in Pelletier and Agnan's study (2019) were insufficient to make comprehensive comparison between them.

Despite progress in the literature, two main limitations remain: (1) near-field condition research is often limited to a narrow range of pesticide molecules and cover crop properties, with inconsistent assessments of soil compartments; and (2) the influence of cover crops is rarely analysed in relation to the physical and chemical properties of the molecules. These gaps prevent a broader understanding of the general applicability of cover crop based remediation strategies across pesticide molecules with contrasting properties.

To address these gaps, we conducted a controlled, three-month greenhouse experiment designed to evaluate the ability of newly sown cover crops to influence the dynamics of existing pesticide residues in soil and soil solution. Specifically, we focused on determining whether differences in pesticide behaviour could be related to their physicochemical properties. For this purpose, we monitored the temporal evolution of 18 active substances and two safeners under three modalities: a control (bare soil) and two contrasting living cover crops densities.

Based on the literature, we considered that cover crops may reduce pesticide leaching primarily by: (1) modifying soil water fluxes through evapotranspiration, thereby concentrating pesticides near the roots; and (2) prolonging their retention within the microbiologically active rhizosphere where bio-degradation is enhanced. Furthermore, following the literature review by Tarla et al. (2020), we considered that rhizosphere-mediated processes play a more important role than plant uptake in controlling pesticide residue dynamics under cover crops. Our main hypothesis was that the influence of cover crops on pesticide dynamics depends on both the physicochemical properties of the molecules and the characteristics of the cover crop. Accordingly, our main objective was to identify trends linking pesticide physicochemical properties with their responses to cover-crop treatments. This included evaluating thresholds in both key molecular properties and cover-crop development that determine whether cover crops exert a measurable effect on residue dynamics in both soil and soil solution compartments. Because our focus was on pesticide residue behaviour within soil compartments, rather than on quantifying microbial processes or plant uptake, microbiological monitoring and plant tissue analyses were not included in the study.

In this paper, we present our numerical results with their standard deviation and propagated uncertainties as: value ±sd standard deviation ±Δ (propagated) measurement uncertainty. When calculating a value from experimental data xi, the propagation of uncertainties Δf due to random and independent measurement errors Δxi, is determined using the general propagation formula:

2.1 Experimental setup

The soil was collected from the top 30 cm of an agricultural plot following a white mustard seed crop (UCLouvain University Farms, Corroy-le-Grand, Belgium; 50.6740° N, 4.6368° E) on 18 December 2023 (day −18; Fig. 1). It constituted a silty soil developed on Quaternary loess characterised by slightly acidic conditions (), low total carbon content (0.89 %), balanced carbon/nitrogen ratio () and a CEC of 11.1 cmolc kg−1. To minimise pesticide contamination, the soil was taken from a certified organic plot (organic conversion 2019–2021) and all modalities were conducted using the same soil. Plants and debris were manually removed from the collected soil, which was then mixed and placed in 10 L plastic pots (0.07 m2 area, 18 cm soil depth), each containing 9.64 ±sd 0.40 ±Δ 0.02 kg of fresh soil (n=35). The pots were then transferred to the greenhouse.

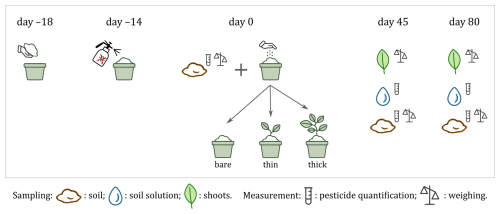

Figure 1Experiment setup, sampling and measurement timeline. Homogenised organic soil was potted on day −18 and treated with 18 pesticide ingredients on day −14, then sown on day 0 with two cover types (a thick winter spelt and a thin multi-species mix) or left bare (control; n=35 pots total). Greenhouse growth was monitored and soil, soil solution and plant biomass were sampled on days 0, 45 and 80. Day 0 corresponds to 5 January 2024.

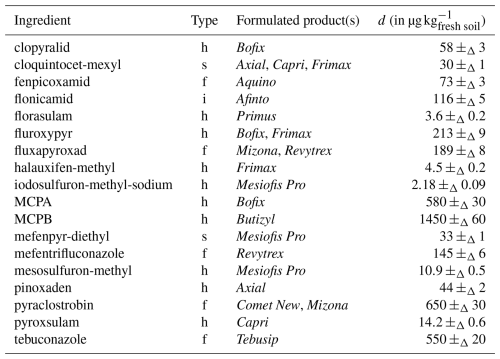

To simulate various pesticide residues from previous crops, a mixture of formulated pesticide products was sprayed on the pot's bare soil in the greenhouse on 22 December 2023 (day −14). The formulated pesticides were selected on the basis of the contrasted physicochemical properties of the active substances, their availability at the University Farms, their possible quantification using a single multi-residue analysis and excluding any root herbicides that could inhibit the germination and growth of the experimental cover crops, regardless of their degradation time. This resulted in the selection of 13 products – containing 18 contrasting different know ingredients: 16 active substances (ten herbicides, five fungicides and one insecticide) and two safener –, applied at their maximum authorised dose (d in kg ha−1, across all authorised crops; Table 1; for details, see Table S1 in Sect. S1 in the Supplement). The composition of the formulated products and the maximum doses authorized (Table S1 in Sect. S1) were obtained from https://fytoweb.be/en (last access: 1 March 2025), the official website of the Belgian Federal Public Services for Health, Food Chain Safety and the Environment for plant protection and fertilising products. For simplicity, interactions between substances were not considered and none were observed during preparation of the spray mixture.

Table 118 applied known ingredients (day −14), with corresponding applied doses (d).

h: herbicide; f: fungicide; i: insecticide; s: safener.

Three cover modalities were tested (Fig. 1). Two types of cover crops with rapid growth: (1) ten pots with winter spelt (Triticum spelta) and (2) ten pots with a multi-species cover (20 % buckwheat, Fagopyrum esculentum; 20 % phacelia, Phacelia tanacetifolia; 20 % vetch, Vicia villosa; and 40 % white mustard, Sinapis alba; seed ); in addition to 15 pots kept bare as a control (for a total of 35 pots in the experiment). In the following, we refer to the cover crops as cover types, while cover types together with the control are collectively referred to as cover modalities. The two cover types were sown on 5 January 2024 (day 0) at a density of 191 ±sd 12 ±Δ 1 kgseeds ha−1 (winter spelt; n=10) and 147 ±sd3 ±Δ 1 kgseeds ha−1 (multi-species mix; n=10), respectively, with the expectation of similar shoot biomass. However, they reached a shoot biomass of 0.43 ±sd 0.04 ±Δ 0.07 tDM ha−1 and 0.25 ±sd 0.08 ±Δ 0.04 tDM ha−1, respectively, on day 45 (n=5), and a shoot biomass of 1.12 ±sd 0.02 ±Δ0.18 tDM ha−1 and 0.36 ±sd 0.09 ±Δ 0.06 tDM ha−1, respectively, on day 80 (n=5). This difference in biomass production may be due to the phytotoxic effect of the applied pesticides to the multi-species mix. Consequently, we analysed pesticide content in relation to biomass difference (referred to as cover density) rather than species difference between the covers, comparing the thick winter spelt cover and the thin multi-species cover mix with the bare control.

The pots were kept in a greenhouse maintained at 20.8 ±sd 1.6 °C and 55 % ±sd 11 % humidity, with 12 h of light per day. They were watered with rain water twice a week at an average rate of ca. 1 L per week, corresponding to an average rainfall of 14 mm per week, leading to an average soil moisture content of 26.36 %DM ±sd 1.76 %DM ±Δ 0.01 %DM (; n=35). To prevent water runoff and uncontrolled leaching, each pot was placed in an individual saucer with a capacity sufficient to retain any excess irrigation water. Saucers were monitored after each watering throughout the experiment and no overflow was observed, confirming that drainage water was fully retained.

Raw data regarding the experimental setup are detailed in Table S2 in Sect. S1.

2.2 Soil, soil solution and plant sampling

An initial soil sampling was performed on five control pots at the time of sowing (day 0; Fig. 1). Subsequently, the sampling was carried out in five pots per cover modality on 19 February 2024 (day 45) and on 25 March 2024 (day 80). On days 45 and 80, three types of samples were collected per pot: (1) plant shoots (for biomass quantification), (2) soil solution sample (for pesticide quantification) and (3) soil sample (for pesticide quantification).

Plant shoots were sampled by cutting the cover at the soil surface. After removal of any dirt, the plant parts were dried in an oven at 60 °C for 24 h, then weighed.

Soil solution was sampled using rhizons (micro suction cups consisting of a 2.5 mm diameter, 10 cm long hydrophilic polyether sulphone membrane with a 0.15 µm porosity; 19.21.21F, Rhizosphere®, Wageningen, the Netherlands, https://www.rhizosphere.com/rhizons/, last access: 1 March 2025), installed vertically in the top 10 cm in the centre of each pot. Soil solution samples were collected using 60 mL polypropylene syringes (BD Plastipak luer lock) manually activated to create a suction of ca. −700 hPa maintained for 16 h using a wooden wedge, 8 h after a 1 L watering. Five replicates were collected per modality for each sampling, except for the control on day 45 and the thin cover on day 80 where only four replicates were collected due to faulty rhizons, connecting pipes and/or syringes (6.7 % ±sd 5.8 % drop-out rate per cover modality). Samples were then transferred to glass vials and kept in the dark in a cold storage (4 °C) until analysis.

When multiple sample types were collected (day 45 and day 80), soil was sampled last, after the plant shoots and soil solution. Each pot was individually emptied into a large container to remove the main roots and to thoroughly mix the soil. From this, 1 kg of fresh soil was sampled on day 0 and day 45, and 200 g on day 80. Fresh soil samples were then frozen at −18 °C and kept in the dark until analysis. An extra 500 g fresh soil sample was collected from each pot to assess soil moisture content (MC) by weighing the soil mass before and after drying in an oven at 70 °C for 48 h: .

As all modalities were conducted on the same homogenised soil, and given that significant changes in bulk soil properties generally require several years of cover cropping (Blanco-Canqui et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2020), we considered the 80 d cover crop growth period insufficient to induce meaningful divergence in soil physicochemical parameters (e.g. pH, organic matter, nutrients). Consequently, these parameters were not monitored beyond the initial soil characterisation.

2.3 Pesticide quantification

Soil and soil solution samples were analysed at the laboratory of the Walloon Agricultural Research Centre (CRA-W) in Gembloux (Belgium) for quantification of the 18 applied active substances and safeners. The quantification of metabolites was not pursued due to laboratory protocol limitations. Frozen soil samples were thawed, extracted by QuEChERS and analysed by liquid chromatography (LC) coupled to a quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (QTOFMS). Soil solution samples were analysed within seven days after collection, extracted with acetonitrile, filtered and analysed on the same LC-QTOFMS instrument. Detail of the analytical method is given in Sect. S2.

Raw quantification data and limits of quantifications (LQ) are available in Tables S3 and S4 in Sect. S1. For data analysis, concentrations below the LQ (<LQ) were assigned a value of and non-detected (ND) values were assigned . Throughout the paper, quantifications of active substance and safeners in soil samples are expressed as compound mass per unit fresh soil mass (), while in soil solution samples they are expressed as compound mass per unit soil solution volume ().

The presence of residual moisture in micropores after gravitational drainage means that fresh soil samples contain compounds both adsorbed to soil particles and dissolved in the residual soil solution. For low solubility compounds, the contribution of the residual solution to the measured soil content is minimal effect on quantification. However, for highly soluble, low-volatility substances (e.g. flonicamid, pyroxsulam), their concentration in the residual solution may exceed that adsorbed to soil particles, potentially introducing bias the analysis. Drying soil samples prior to analysis does not resolve this issue, as low-volatility compounds remain in the soil while other substances may volatilise during the drying, introducing further bias. This limitation applies broadly to studies quantifying pesticides in soil and complicates comparisons with soil solution measurements. In this study, it prevented us from determining a total mass balance simply by combining soil content and soil solution concentration, as the residual soil solution would effectively be double counted. Nevertheless, to allow direct comparison between compartments, we converted soil solution concentration to an equivalent fresh soil content (in µg kg−1) by multiplying by the fraction of soil solution per unit mass of fresh soil, noting that the soil content inherently includes some of the soil solution.

2.4 Pesticide properties data source

Physicochemical properties of the active substances and safeners, and the threshold interpretations were extracted from the Pesticide Properties DataBase (PPDB; Lewis et al., 2016) on 3 May 2024 and are summarised in Tables S5 and S6 in Sect. S1. These properties include: typical soil persistence (DT50soil, in days) and soil sorption coefficient (Koc, in mL g−1) for the persistence and mobility in soil, respectively; water solubility at 20 °C (s, in mg L−1) and groundwater ubiquity score (GUS, dimensionless) for the transfer to soil solution and tendency to leach; vapour pressure at 20 °C (p, in mPa) and Henry's law constant (kH, in Pa m3 mol−1) for the transfer to air; n-octanol–water partition coefficient (i.e. lipophilicity) at pH 7 and 20 °C (Kow, dimensionless), bioconcentration factor (BCF, in L kg−1) and relative molecular mass (m, dimensionless) for the uptake into plants.

2.5 Data treatment

Interquartile range outlier analysis conducted in MS Excel per sampling date and compartment (across all modalities) showed that a minority (no more than five) of the 18 active substances and safeners were affected by outlier values per sample. Consequently all samples were retained in the dataset and no outlier were excluded.

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to assess patterns in the quantification data across compartments, modalities and sampling dates. Prior to analysis, the data were subjected to a centred log-ratio transformation using the R function compositions::clr (van den Boogaart et al., 2005) to account for compositional constraints. The PCA was then performed in R using FactoMineR (Lê et al., 2008), ensuring that data were centred and scaled, and the results were visualised using factoextra (Kassambara and Mundt, 2016) and ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016). Permutational multivariate analyses of variance (PERMANOVA) were performed on the PCA to discuss results, using the R function vegan::adonis2 (Oksanen et al., 2025). The homogeneity of the multivariate dispersion between the analysed groups was confirmed (p-value>0.52), supporting the robustness of the observed patterns.

Standard deviation for the differences in pesticide content between cover modalities (cover types versus control) was calculated as the propagation of the standard deviations of the cover type and the control (with no correlation factor as the cover modality samples were unpaired):

To assess whether the differences in pesticide content were statistically significant, we performed individual unilateral t-tests for each cover-crop type versus the control (implemented in MS Excel using the T.DIST.RT function). We limited the analysis to pairwise comparisons with the control because the two cover-crop types differ not only in density but also in species composition, making direct statistical comparisons between them difficult to interpret. These tests therefore evaluate whether the concentration difference between each cover type and the control is significantly different from zero (positive or negative).

Data visualisations were performed in R (R 4.4.2, R Core Team, 2024), using ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016).

3.1 Active substance behaviour by compartment

Raw quantification data are available in Table S3 (Sect. S1) and additional visualisations of the results can be found in Figs. S2 and S3 (Sect. S6).

3.1.1 Soil content

Applied doses (day −14) ranged from 2.18 ±Δ 0.09 µg kg−1 (iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium) to 1450 ±Δ 60 µg kg−1 (MCPB; Table 1). By day 0, average pesticide contents in soil samples (in all modalities) ranged from 0.25 ±sd 0.20 µg kg−1 (pinoxaden) to 730 ±sd 260 µg kg−1 (MCPA), corresponding to residues from 0 % (no detection: iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium and mefenpyr-diethyl) to 130 % ±Δ 50 % (MCPA) of the initial applied mass, with a median of 48 % over the 18 active substances and safeners. All but three molecules (pinoxaden, iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium and mefenpyr-diethyl) were quantified in all samples. In particular, seven active substances (clopyralid, fluroxypyr, fluxapyroxad, MCPA, mefentrifluconazole, mesosulfuron-methyl and tebuconazole) showed residue levels compatible with 100 % of the initial mass, linked to high applied dose (d⩾145 µg kg−1), very low volatility ( mPa) and/or moderate to long persistence in soil (DT50soil>30 d). In contrast, pinoxaden, iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium and mefenpyr-diethyl, characterised by low applied dose (d<5 µg kg−1), high water solubility (s>1000 mg L−1) and/or short soil persistence (DT50soil<30 d), had quantification rates of 80 %, 20 % and 0 %, respectively.

By day 45, soil contents had decreased from below 0.20 µg kg−1 (cloquintocet-mexyl and pinoxaden; lowest LQ) to 310 ±sd 80 µg kg−1 (tebuconazole). This corresponded to residues from 0 % (no detection) to 62 % ±Δ 15 % (fluxapyroxad) of the initial applied mass, with a median below 0.5 %. This aligns with literature showing that most pesticide loss occurs within the first weeks after application via evaporation, photolysis and hydrolysis (Bedos et al., 2002; Ferrari et al., 2003; Gish et al., 2011). Seven active substances (fenpicoxamid, fluxapyroxad, MCPA, mefentrifluconazole, mesosulfuron-methyl, pyraclostrobin and tebuconazole) were quantified in all samples, exhibiting at least two of the following characteristics: high applied doses (d⩾145 µg kg−1), low water solubility (s<10 mg L−1), high soil sorption (Koc>4000 mL g−1) and/or long soil persistence (DT50soil>100 d) – except for MCPA, which has a high solubility (s=250 000 mg L−1) but was applied at the third highest dose (d=580 µg kg−1), leaving detectable residues. Five active substances (clopyralid, flonicamid, fluroxypyr, MCPB and pyroxsulam) had quantification rates between 20 % and 80 %, while six molecules (cloquintocet-mexyl, florasulam, halauxifen-methyl, iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium, mefenpyr-diethyl and pinoxaden) were not quantified in any sample. With the exception of clopyralid, fluroxypyr and mefenpyr-diethyl, these molecules have a persistence in soil of 5 d or less, explaining their rapid disappearance. Despite its short persistence in soil (DT50soil=3.5 d) and medium applied dose (d=73 µg kg−1), fenpicoxamid was quantified in 100 % of the soil samples due to its high soil sorption (Koc=53 233 mL g−1) and very low water solubility (s=0.041 mg L−1). The low quantification rates of clopyralid and fluroxypyr in soil samples are probably due to their high water solubility (s>1000 mg L−1) and relatively high LQ in soil samples (LQ⩾2.5 µg kg−1).

By day 80, soil contents ranged from below 0.20 µg kg−1 (cloquintocet-mexyl and pinoxaden; lowest LQ) to 490 ±sd 150 µg kg−1 (tebuconazole). This corresponded to residues from 0 % (no detection) to 120 % ±Δ 30 % (fluxapyroxad) of the initial mass (median<0.1 %). The seven active substances quantified at a rate of 100 % on day 45 were still quantified in all samples on day 80, with the addition of MCPB (highest applied compound). The remaining ten molecules were quantified in no more than 13 % of the samples. Compared to day 45, soil contents appeared to increase for five of the eight molecules systematically quantified above their LQ (fenpicoxamid, fluxapyroxad, mefentrifluconazole, MCPB and tebuconazole), particularly under the thin cover and the control; the observed increases ranged from 36 % ±Δ 48 % for fenpicoxamid to 220 % ±Δ 140 % for MCPB (excluding the thick cover on day 80 from the averages). These apparent increases even exceeded the initial mass applied (day −14) for fluxapyroxad, mefentrifluconazole and tebuconazole, reaching contents of 140 % ±Δ 20 %, 120 % ±Δ 20 % and 110 % ±Δ 20 % of the initial mass, respectively. These molecules generally show the longest soil persistence (DT50soil>100 d) and/or the highest soil sorption (Koc>4000 mL g−1) of all applied compounds, with the exception of MCPB, whose presence in soil was renewed by the degradation of MCPA, of which it is a major metabolite. This apparent anomaly is likely due to differences in soil sampling procedures between the first two soil samplings (day 0 and day 45) and the third sampling (day 80). On day 80, the reduced soil mass sampled preferentially selected smaller aggregates, mainly from the topsoil where soil-adsorbed pesticide contents are higher (rather than larger aggregates from the subsoil, which have lower soil-adsorbed pesticide contents). This may have introduced a bias that artificially increased the quantified contents of persistent, poorly soluble and/or soil-adsorbed pesticides compared to the more homogeneous samples of day 0 and day 45. As a result, the temporal trends observed in the soil compartment are likely biased; however, as sampling was consistent between modalities at each individual date, comparisons between modalities at a given date remain valid.

In comparison to our results, Silva et al. (2019), reported higher pesticide contents in agricultural topsoils collected in situ across Europe in 2015. These elevated contents are likely to be due to differences in study design: our soil samples were taken from an organic soil with a single pesticide application on day −14, whereas Silva et al.'s study targeted conventional agricultural fields with recurrent pesticide use, selecting countries and crops with the highest pesticide application per hectare in Europe. As a result, they reported quantified residue contents as high as 2000 (glyphosate) compared with our highest applied dose of 1450 µg kg−1 (MCPB). In addition, our study simulated cover crop conditions during a fallow period, with soil sampled under fully developed cover 94 d after the pesticide treatment (day 80); in contrast, samples of Silva et al. were collected between April and October, coinciding with the period of application of most pesticides. Agnan et al. (2019) reported pesticide contents similar to ours in soil under maize cultivation, up to 270 (S-metolachlor) eight days after application; these values are comparable to those observed in our study on day 0 (14 d after application), where contents reached a maximum of 730 µg kg−1 (MCPA).

3.1.2 Soil solution concentration

By day 45, concentrations in soil solution samples ranged from below 0.025 µg L−1 (halauxifen-methyl, lowest LQ) to 27 ±sd 13 µg L−1 (clopyralid), corresponding to residues from 0 % (no detection) to 10 % ±Δ 5 % (clopyralid) of the initial mass (median<0.1 %). Seven active substances (clopyralid, florasulam, fluroxypyr, fluxapyroxad, mesosulfuron-methyl, pyroxsulam and tebuconazole) were quantified in all samples. These molecules are characterised by high applied dose (d>145 µg kg−1), high leachability (GUS>2.8) and/or high solubility (s>1000 mg L−1). Four others (flonicamid, MCPA, MCPB and mefentrifluconazole) had quantification rates between 7 % and 93 %, while five molecules (cloquintocet-mexyl, halauxifen-methyl, iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium, mefenpyr-diethyl and pyraclostrobin) were not quantified in any sample. The non-detected substances are characterised by a persistence in soil of 5 d or less, a low leachability (GUS<1.8) and/or low solubility (s<10 mg L−1).

By day 80, concentrations had dropped further from below 0.025 µg L−1 (halauxifen-methyl, lowest LQ) to 9.9 ±sd 4.1 µg L−1 (tebuconazole), corresponding to residues from 0 % (no detection) to 3 % ±Δ 5 % (mesosulfuron-methyl) of the initial mass (median<0.1 %). Three of the seven active substances quantified at a rate of 100 % on day 45 (fluxapyroxad, mesosulfuron-methyl and tebuconazole) were still quantified in all samples on day 80. The other four are characterised by short soil persistence (DT50soil<30 d) and high soil mobility (Koc<75 mL g−1), resulting in faster degradation and transfer out of the sampled topsoil. Eight active substances (clopyralid, flonicamid, florasulam, fluroxypyr, MCPA, mefentrifluconazole, pyraclostrobin and pyroxsulam) were detected with rates between 13 % and 80 %, while five other molecules (cloquintocet-mexyl, halauxifen-methyl, iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium, MCPB and mefenpyr-diethyl) were never detected, consistent with day 45 trends.

Compared to our results, Agnan et al. (2019) reported similar pesticide concentrations in soil solution collected at a depth of 50 cm, with median values ranging from 0.01 µg L−1 (2,4-D) to 5.20 µg L−1 (S-metolachlor) over their four-year maize field study (LQ from 0.01 to 0.60 µg L−1). Similarly, Giuliano et al. (2021) observed maximum soil solution concentrations at 1 m depth between 1.31 µg L−1 (glyphosate) and 28.96 µg L−1 (mesotrione) during their eight-year maize field study (LQ from 0.01 to 0.05 µg L−1). In contrast, Vryzas et al. (2012) reported significantly higher concentrations, reaching up to 1166 µg L−1 (atrazine) at 35 cm depth in their four-year maize field study (LQ from 0.005 to 0.05 µg L−1). This discrepancy can be attributed to preferential flow mechanisms facilitated by deep clay cracks in high clay soils under their semi-arid conditions (Vryzas et al., 2012). Compared to these studies, our relatively high LQ (from 0.025 to 1.5 µg L−1) limited our ability to follow all 18 active substances and safeners in the soil solution compartment.

3.1.3 Differences in compartments

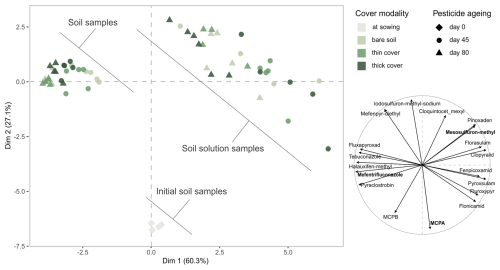

To analyse both compartments simultaneously and to integrate data from all sampling dates, we performed a PCA on all quantification results (Fig. 2). Sampling date, compartment and physicochemical properties were not included as input variables but used only for visual grouping in the score plot. The right panel of the figure shows the projection of each compound on the first two dimensions of the PCA. Looking the loading plot (Fig. 2, right panel) and the physicochemical properties of the compounds (Table S5 in Sect. S1), we see that the first dimension of the PCA, accounting for 60 % of the variance, separated the molecules in two groups: (1) negative values corresponded to substances such as mefentrifluconazole and tebuconazole, which have high soil sorption, high lipophilicity, low water solubility and/or long soil persistence; and (2) positive values corresponded to substances such as clopyralid or pyroxsulam, which have low soil sorption, low lipophilicity, high water solubility and/or short soil persistence. The second dimension, accounting for 27 % of the variance, further differentiated the active substances: (1) negative values corresponded mainly to MCPA and MCPB, which have high applied doses and low molecular masses while (2) positive values corresponded to substances such as iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium and mesosulfuron-methyl, which have lower applied doses and higher molecular masses.

Figure 2Principal component analysis (PCA) of all quantified samples: we observe that the relative profile of compounds in soil and soil solution samples changed over time. Left: score plot of the samples, illustrating their distribution along the first two principal components based on their compound profile. Right: loading plot of the quantified compounds, indicating how each contributes to the separation of samples along the first two principal components. The three molecules in bold in the right panel were selected for the individual analysis detailed in Sects. S3 and S4. The thick cover modality refers to the winter spelt cover (reaching a shoot biomass of 1.12 tDM ha−1 on day 80) and the thin cover modality refers to the multi-species mix (reaching a shoot biomass of 0.36 tDM ha−1 on day 80).

The first principal component clearly separated soil and soil solution samples, indicating that compartment was the main contributor to variance. Initial soil samples (day 0) clustered on the negative side of the second dimension, characterised by highly applied, low molecular mass molecules. Over time soil samples moved to the upper left of the score plot (day 45), reflecting an increased contribution from molecules with higher soil sorption, bioconcentration or persistence, before shifting further to the left (day 80). In contrast, soil solutions samples shifted to the upper right (day 45), influenced by molecules with lower soil sorption, bioconcentration or persistence, before shifting up and left (day 80), suggesting a decreased influence of highly applied, low molecular mass molecules applied at higher doses.

These visual patterns were statistically supported by PERMANOVA, which demonstrated that soil compartment, sampling date and cover modality each independently and significantly influenced the distribution of pesticide molecule levels. Compartment alone accounted for 68.5 % of the variance (p-value<0.001), while date and modality explained 19.4 % (p-value<0.001) and 16.0 % (p-value<0.01), respectively. Combined, these three factors explained 88.3 % of the variance, increasing to 91.5 % when interactions were included. These results confirm that the separation observed in PCA space reflects differentiated trajectories of molecule evolution across soil compartments, sampling times and cover modalities.

3.2 Hypothesised mechanism

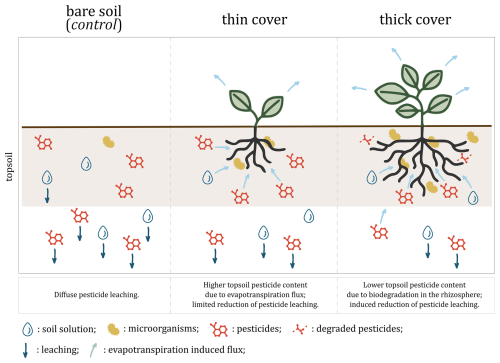

The shifts analysed in the previous section highlight the dynamic speciation and redistribution of compounds within each soil compartment over time. PERMANOVA results showed that, after soil compartments and sampling dates, cover modalities were the third most statistically significant factor explaining the variability in pesticide content between samples. Focusing on soil samples, the evolution of pesticide content over time and between cover modalities – detailed in Sects. S3 and S4 – showed a dual trend after 80 d: (1) higher retention under thin cover (relative to thick cover and control), and (2) greater reduction under thick cover (relative to thin cover and control). These patterns fit with our two main considerations from the literature: (1) that rhizofiltration, driven by evapotranspiration, contributes to pesticide retention under less developed covers, and (2) that enhanced microbial biodegradation under thicker, more developed covers drives pesticide degradation. This leads to the following hypothesised mechanism:

-

As the cover develops, we hypothesise that the thin cover modifies soil water fluxes through evapotranspiration, a process that is likely to acts as rhizofiltration by retaining in the rhizosphere pesticide substances that would otherwise leach deeper into the soil profile (Tarla et al., 2020). The higher contents under the thin cover crop would therefore reflect a greater retention compared to the leaching observed under the control, rather than an absolute increase in residue (Fig. 3, left and central panels). This would be consistent with previous studies showing that cover crops increase soil permeability while decreasing drainage by removing soil moisture through evapotranspiration (Alletto, 2007; Unger and Vigil, 1998) and may induce the resurgence of certain pesticide molecules that have started to leach down in the soil profile (Agnan et al., 2019). However, this retention effect only became apparent 80 d after sowing, suggesting that it would depend not only on the stage of development of the cover, but also on an adaptation period required to modify soil water fluxes and reverse initial leaching. While this effect was evident in soil samples, it was not significant in soil solution samples under the thin cover on day 80 or under the thick cover on day 45 (at equivalent biomass density of ca. 0.4 tDM ha−1). As evapotranspiration, leaching, microbial activity and metabolites were not analysed, we cannot confirm this hypothesised mechanism.

-

As the cover continues to grow and its root system develops, rhizospheric microbial activity increases, enhancing the biodegradation of pesticide residues (Cycoń et al., 2017; Eevers et al., 2017; McGuinness and Dowling, 2009). This process likely reduced the pesticide content in the soil under the thick cover compared to the control, as biodegradation would counteract the increased retention of the cover (Fig. 3, right panel). This biodegradation probably acts in parallel to enzyme-driven catalysis from root exudates, fungi or other microorganisms, and to interaction with rhizospheric organic matter and plant uptake. As microbial abundance and diversity were not monitored and pesticide content in plant material (roots nor shoots) was not quantified, these mechanisms remain undifferentiated.

Figure 3Hypothesised mechanism: cover crops reduce pesticide leaching by altering soil water fluxes through evapotranspiration and concentrating pesticides near roots where they are efficiently degraded by edaphic microbiota. The thick cover modality refers to the winter spelt cover (reaching a shoot biomass of 1.12 tDM ha−1 on day 80) and the thin cover modality refers to the multi-species mix (reaching a shoot biomass of 0.36 tDM ha−1 on day 80).

The dual pattern of pesticide retention under the thin cover and degradation under the thick cover was particularly evident after 80 d, when the root system of the cover crops had developed sufficiently. This was mainly observed in soil samples, where pesticide contents were higher than in soil solution. In soil solution samples, the effect was detectable at concentrations above the LQ, with only a few statistically significant differences between the cover types and the control, warranting further investigation. In this study, a biomass of at least 1.12 ±sd 0.02 ±Δ 0.18 tDM ha−1 was required to achieve a significant reduction of the active substances in both soil and soil solution by day 80. This threshold is lower than the 2 tDM ha−1 biomass reported by Alletto et al. (2012) as necessary to observe similar effect in field experiments. Note that our thin and thick covers are composed of different species: species-specific characteristics beyond growth rate and root density may influence these effects. The observed patterns were consistent for molecules with contrasting physicochemical properties (see Sects. S3 and S4), suggesting that these effects may be generalised to other pesticide compounds, with varying magnitudes (see also Figs. S2 and S3 in Sect. S6). The magnitude of the effect correlated with soil mobility and water solubility, suggesting that the properties of the compounds may help predict whether cover crops will significantly alter their fate in soil.

3.3 Physicochemical properties

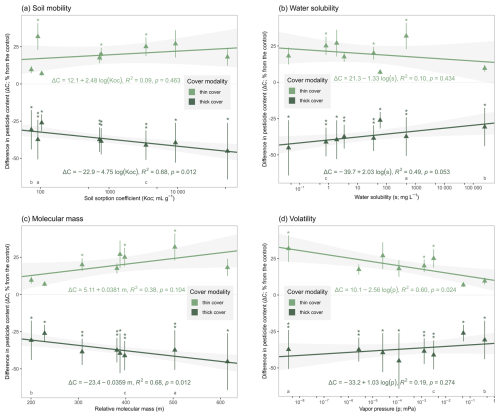

Building on the previous results, this section examines the relationship between the physicochemical properties of the applied pesticide compounds and the differences between their soil content under both cover types and the control on day 80. Although only eight active substances showed quantified soil contents on day 80, analysis of individual physicochemical trends provide insights into the processes influencing the interaction between soil covers and pesticide compound behaviours. Specifically, we examined four physicochemical properties – soil mobility (Koc), water solubility (s), molecular mass (m) and volatility (p) – which correspond to persistence in soil, transfer to soil solution, tendency for plant uptake and transfer to air, respectively (Fig. 4). In general, the deviation from the control (i.e. the absolute value of the difference in content ) increased with lower soil mobility (i.e. higher Koc; Fig. 4a) and higher molecular mass (Fig. 4c), whereas it decreased with higher water solubility (Fig. 4b) and higher vapour pressure (Fig. 4d).

Figure 4Differences in pesticide soil contents compared to the control (bare soil) on day 80, for the eight active substance with 100 % quantification rate and for both cover types, in function of the active substance's: (a) soil mobility (as log (Koc)), (b) water solubility (as log (s)), (c) molecular mass (m) and (d) volatility (as log (p)). The coloured lines represent linear fits for both cover types, with 90 % confidence intervals. Stars above the error bars depict statistically significant unilateral differences between the cover type and the control at each date (∗: ;  : ). Three contrasting molecules (see Sects. S3 and S4) are tagged with a letter below them (mesosulfuron-methyl: a; MCPA: b; mefentrifluconazole: c). The thick cover modality refers to the winter spelt cover (reaching a shoot biomass of 1.12 tDM ha−1 on day 80) and the thin cover modality refers to the multi-species mix (reaching a shoot biomass of 0.36 tDM ha−1 on day 80).

: ). Three contrasting molecules (see Sects. S3 and S4) are tagged with a letter below them (mesosulfuron-methyl: a; MCPA: b; mefentrifluconazole: c). The thick cover modality refers to the winter spelt cover (reaching a shoot biomass of 1.12 tDM ha−1 on day 80) and the thin cover modality refers to the multi-species mix (reaching a shoot biomass of 0.36 tDM ha−1 on day 80).

For soil mobility, the soil sorption coefficients for the 18 applied active substances and safeners ranged from 1.6 (flonicamid) to 53 000 mL g−1 (fenpicoxamid) and substances quantified by day 80 had sorption coefficients above Koc⩾74 mL g−1 (MCPA). By day 80, the most mobile molecules had been transferred out of the soil or degraded, limiting the effect the cover crops could have on them. A linear fit, with its 90 % confidence interval, of the deviation from the control under the thick cover (R2=0.68, p-value<0.05; Fig. 4a) indicated that compounds with soil sorption coefficient greater than mL g−1 experienced a reduction in soil content of at least 33 %. Higher soil sorption ensured lower mobility and longer retention of the molecules within the microbiologically active rhizosphere, allowing the effects of the thick cover to fully manifest. While sorbed molecules are typically less bioavailable, higher soil organic matter from root systems and exudates can both enhance pesticide adsorption and facilitate desorption. This dual process can enhance biodegradation by supporting microorganisms in soils with high organic matter content, enabling them to break down pesticides more efficiently (Eevers et al., 2017).

Water solubility of the 18 studied active substances and safeners ranged from 0.041 (fenpicoxamid) to 250 000 mg L−1 (MCPA), with this range being largely observed up to day 80. A linear fit (R2=0.49, p-value≃0.05; Fig. 4b) indicated that compounds with solubility under mg L−1 had their soil content reduced by at least 33 % under the thick cover. More soluble compounds leached more rapidly outside of the rhizosphere, reducing the effect of the cover on their soil content.

Relative molecular mass of the studied compounds ranged from 190 (clopyralid) to 620 (fenpicoxamid) and substances quantified by day 80 had molecular mass above m⩾200 (MCPA). A linear fit (R2=0.68, p-value<0.05; Fig. 4c) indicated that compounds with molecular mass above m⩾280 ±Δ 140 had their soil content reduced by at least 33 % under the thick cover. However, the 18 molecules analysed in this study show a general inverse relationship between molecular mass and solubility. This may suggest that compounds with lower molecular mass may be less degraded due to increased leaching and not to the intrinsic effects of molecular mass. This would explain the discrepancy with some existing literature, such as that reported by the meta-analysis by Jia et al. (2023).

For volatility, the vapour pressure of the studied compounds ranged from (mesosulfuron-methyl) to 1.4 mPa (clopyralid), with substances quantified up to day 80 having vapour pressures less than p⩽0.4 mPa (MCPA). A linear fit (R2=0.60, p-value<0.05; Fig. 4d) indicated that compounds with vapour pressures greater than mPa had their soil content increased by less than 20 % higher under the thin cover, suggesting that volatilisation resulted in a greater loss of soil content before the cover crop could take effect. While the cover still had an effect on the more volatile substances, it was less pronounced that for the less volatile molecules.

While most deviations from the control in soil samples under the thick cover were significantly different from zero on day 80, differences under the thin cover or in soil solution samples were generally not statistically significant. The same pattern was observed at day 45. While this may suggest a lack of effect of the cover crops at lower biomass or earlier time, it could also be due to insufficient statistical power in the experimental setup. To guide future experimental design, we calculated the minimum sample sizes required to achieve at least 80 % statistical power under similar conditions of pesticide compound levels, variances between independent replicates and cover developments (see Sect. S5 for details). For soil samples, adequate statistical power was already achieved on day 80 with five replicates (except for MCPA, which required eight replicates); however, for soil solution samples, a median sample size of 14 replicates was required (with a maximum of 118 for tebuconazole; see Table S8 in Sect. S5).

In conclusion, cover crops affect the presence of pesticide compounds in the soil over a wide range of physicochemical properties, as highlighted by the non-zero deviation from the control for both cover types and all quantified substances on day 80 in the soil samples. Our results suggest that even persistent or adsorbed pesticides continue to be degraded as long as cover crops are maintained. Under the thick cover, compounds with moderate to non-mobility in soil (Koc⩾160 mL g−1), low to high water solubility (s⩽1400 mg L−1) and/or moderate to high molecular mass (m⩾280) experienced at leas a 33 % reduction in soil content by day 80, compared to the control (where leaching occurred). In Wallonia (southern half of Belgium), 141 authorised active substances – including 30 % of the most frequently used active substances in the period 2015–2020 (Corder, 2023) – fall within all three thresholds and mainly concern potato, sugar beet and winter cereal crops (Lewis et al., 2016, last access: 3 May 2024; https://fytoweb.be/en, last access: 1 November 2024). The adoption of dense cover crops during the fallow period in Wallonia could therefore play a important role in degrading pesticide before they leach to groundwater.

3.4 Agronomic interest

The results of the previous sections show that thick cover crops can significantly reduce the environmental impact of pesticides by decreasing their presence in the soil and limiting their transfer to groundwater. While pesticide concentration in soil solution may appear negligible compared to soil content, cumulative leaching can lead to significant groundwater contamination, particularly during aquifer recharge periods. The observed reductions in pesticide levels highlight the potential of thick cover crops to protect water quality during the fallow period. Although this effect maybe limited for highly volatile pesticides (which are lost to the atmosphere before cover crops can affect them) and for highly soluble molecules (which may leach before cover crops establish), it represents an important step in phytoremediation. Unlike long-term strategies such as multi-year miscanthus (Miscanthus×giganteus) plantations for trace metal remediation or soil excavation, cover crops provide a flexible approach without limiting field availability. As the effects of cover crops on pesticide dynamics only become apparent after a period of growth and adaptation, cover crops should be established as soon as possible after harvest to maximise pesticide degradation.

Cover crops influence soil microbial dynamics by altering microbial abundance, activity and diversity (Finney et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2020), thereby likely increasing the biodegradation of pesticide residues. However, this increased degradation should not be used as a justification for maintaining or increasing pesticide use as numerous studies have shown that pesticide use can negatively affect soil microbial communities, altering microbial diversity and enzymatic activity in soils (Chowdhury et al., 2008; Cycoń et al., 2017; Das et al., 2016). In addition, pesticide residues can directly inhibit the establishment of subsequent crops, including cover crops, thereby reducing biomass production and transpiration rates (Feng et al., 2024; Palhano et al., 2018; Rector et al., 2020; Silva, 2023), which may explain the underdevelopment observed in our thin multi-species cover mix. Therefore, to optimise their phytoremediation potential, cover crops should be integrated into broader agroecological strategies, such as integrated pest management (IPM), to reduce reliance on pesticides and increase ecosystem resilience. Reducing pesticide use – through pest pressure management, agricultural system redesign improved application techniques – is the primary strategy for mitigating pesticide-related environmental externalities and protecting surface and groundwater quality. This includes prioritising non-chemical methods for cover crop termination to avoid introducing new pesticide residues into the soil.

The efficiency of phytoremediation depends on both the botanical family of the cover crop and the microbial strains present in the soil (Hussain et al., 2009; Jia et al., 2023; Wojciechowski et al., 2023). Certain plant species are more effective than others at retaining or degrading specific pesticide compounds, with annuals often showing higher remediation efficiencies than perennials due to their rapid biomass growth and high transpiration rates (Jia et al., 2023). Our results suggest that cover crops can reduce pesticide residues across a broad range of molecules and that choosing fast-growing species with dense root systems can further enhance their remediation potential, as has also been observed in weed management (MacLaren et al., 2019).

In addition to their role in phytoremediation, cover crops also affect the fate of pesticides through processes not investigated in this study, such as plant uptake. Pesticide translocation within plants depends on physicochemical properties such as lipophilicity (Kow), water solubility and molecular mass. Although accumulation is generally greater in roots (Chuluun et al., 2009), compounds with Kow values between 1 and 3 can be transported from roots to shoots (Jia et al., 2023). Although our study did not address the ultimate fate of pesticide-contaminated biomass, the risk of hazardous pesticide residues accumulating in cover crops is likely to be minimal if the preceding crop was considered safe for food or feed and since plant uptake generally plays a smaller role in pesticide dissipation than soil degradation (Tarla et al., 2020). However, a notable exception concerns late-flowering cover crops that could provide contaminated floral resources for pollinators following a non-entomophilic main crop (Morrison et al., 2023; Sanchez-Bayo and Goka, 2014; Zioga et al., 2023; Tarano et al., 2025). In such cases, selection of non-flowering covers or topping before flowering may help reduce risks.

Finally, following our hypothesised mechanism, any practice that increases living cover and microbial activity may contribute to pesticide degradation. Crop diversification, vegetative buffers or permanent cover all promote a more active soil microbiota, thereby facilitating pesticide degradation and (directly or indirectly) reducing leaching (Krutz et al., 2006; Venter et al., 2016). This approach could be particularly relevant for plots transitioning to organic farming, accelerating the reduction of pesticide residues in the soil. Cover crops also play a critical role in reducing erosion-related pesticide runoff, making them valuable in protecting surface water quality as well. By acting directly in the soil compartment where pesticides are applied, such measures also help to reduce pesticide contamination in other environmental compartments. This can directly improve drinking water quality, rather than having to treat water at the point of extraction, and it is conceivable that agri-environmental subsidies for long-term, dense cover crops could be partly funded through drinking water tariffs, as this practice reduces downstream costs associated with water remediation and sanitation.

3.5 Limitations and perspectives

This study provides valuable insights into the role of cover crops in pesticide fate and persistence, but has several limitations.

Although our interpretation of pesticide behaviour draws on the widely acknowledged role of rhizosphere-mediated microbial processes in pesticide biodegradation, we were unable to directly monitor microbial activity. Further research integrating both pesticide quantification and microbial activity measurements would provide valuable mechanistic understanding of the processes driving residue dynamics under cover crops. Similarly, although we tested two different types of cover crops, their different growth patterns led us to asses cover density rather than the specific effects of cover species. Further experiments comparing single and multi-species covers, both at different densities, would improve our understanding of these processes.

Building on this limitation, our analysis focused on above-ground biomass density as the primary indicator, despite the cover crops comprising different species. This approach was motivated by the markedly different development patterns of the two cover types. Interestingly, at comparable biomass densities (day 45 for the thick cover and day 80 for the thin cover), pesticide behaviour appeared similar. This suggests that shoot biomass density – used here as a proxy for root development – may be more influential than species composition in determining pesticide dynamics. Therefore, selecting cover crop species that can tolerate residual pesticides and establish rapidly may have a greater impact on mitigating pesticide transfer than maximising species diversity. While this prevents a direct evaluation of species-specific effects, it highlights the importance of biomass development. Furthermore, the poor establishment of the thin cover crop may have resulted from the phytotoxic effects of the applied pesticides. This hypothesis warrants further investigation, including the use of control pots growing cover crops without pesticide residues.

Metabolites can be more toxic and persistent than parent compounds, and biodegradation typically involves successive transformations – oxidation, reduction, hydrolysis, conjugation or polymerization – which further influence persistence (Fenner et al., 2013; Tixier et al., 2000, 2002). The lack of their analysis is a key limitation of our study. For example, mefentrifluconazole produces trifluoroacetate (TFA), as highly persistent polyfluorinated metabolite, raising concerns about drinking water contamination by per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in Europe (Burtscher-Schaden et al., 2024; Joerss et al., 2024; Freeling and Björnsdotter, 2023; PAN Europe and Générations Futures, 2023). While our results suggest that thick cover crops accelerate the degradation of mefentrifluconazole (see Sect. S4), the fate of its metabolites remains uncertain. Future research should therefore include these metabolites and evaluate the role of co-formulants to better understand degradation dynamics.

Although greenhouse experiments cannot fully replicate field conditions, mesoscale setups are relevant for studying pesticide fate and ecotoxicological effects (Chaplin-Kramer et al., 2019). In our study, 10 L pots allowed controlled assessments but limited leaching assessments due to the shallow soil depth. The inability to collect soil solutions at multiple depths highlights the need for field validation, as deeper soil profiles may influence observed effects such as increased leaching or resurgence of residues from lower horizons due to evapotranspiration-induced water fluxes (Agnan et al., 2019). Moreover, the soil disturbance involved in collecting and setting up the pots may have influenced our results. However, this disturbance is comparable to the effects of a 25 cm-deep tillage prior to sowing cover crops, thus not completely out of realistic agricultural conditions. Root channels and earthworm burrows, common under field conditions, also enhance microbial degradation (Mallawatantri et al., 1996), while simultaneously creating preferential flow paths that may accelerate pesticide transport beyond microbial activity zones. A better understanding of the vertical transfer dynamics, runoff and temporal concentration variations is essential to assess the cover crop ecosystem service of groundwater pollution mitigation. Furthermore, while our controlled experiment isolated soil effects, variations in soil properties (e.g. pH, organic matter content) and environmental factors (e.g. temperature, rainfall, field heterogeneity) are likely to influence pesticide behaviour in situ.

While our study assessed pesticide persistence using a linear framework based on individual physicochemical properties, we acknowledge that complex interactions between pesticides and other contaminants may introduce non-linear effects. Furthermore, our approach focused on generalisable trends and did not take into account the molecular specificity of individual active substances, although structural features such as aromatic rings and halogen atoms (e.g. chlorine, fluorine) have a strong influence on pesticide persistence and biodegradability (Calvet et al., 2005; Naumann, 2000).

To refine our understanding of pesticide retention and degradation mechanisms under different cover conditions, future research should prioritise the following key areas:

-

direct measurement of soil microbial biomass and activity to better characterise microbial interaction with the cover and contributions to pesticide degradation;

-

systematic assessment of pesticide metabolites to confirm hypotheses on degradation (vs. transfers) and evaluate their persistence and potential ecological impact;

-

lowering the LQ in soil solution analyses to improve interpretation and allow more accurate tracking of pesticide concentrations in soil solution and leaching potential. This requires increased sampling volumes, either by using additional rhizons in field settings or by installing full-scale lysimeters, or improved laboratory protocols and/or machinery;

-

increasing sampling frequency to refine degradation kinetics and establish biomass thresholds relevant to pesticide degradation, and sample soil and soil solution at different depths to better assess the vertical mobility of pesticide residues;

-

testing different cover crop species and densities to precise specifications required for optimal pesticide degradation. Multi year field trials under different climatic conditions, as well as multi-site trials with different pedoclimatic and microbiota conditions would provide a more comprehensive assessment. Control treatments with cover crops grown on untreated soils would help to isolate the effects of pesticide residues on biomass production, evapotranspiration and microbial activity;

-

investigate pesticide uptake by cover crops (while differentiating root and shoot uptake) to complete mass balance assessments and evaluate potential risks, including exposure pathways for pollinators.

Addressing these limitations will improve our understanding of the influence of cover crops on the fate of pesticide residues in the soil and help support more sustainable agricultural management practices.

In this paper, we investigated the influence of newly sown cover crops on soil pesticide residues from previous growing seasons by comparing pesticide levels in soil and soil solution over a three months greenhouse experiment under three modalities: a thin cover, a thick cover and a control (bare soil; Fig. 1).

Our results show that living cover crops alter the fate of pesticide residues in soil through two complementary mechanisms: retention of residues in the topsoil under low biomass, and enhanced degradation under higher biomass, both influenced by the physicochemical properties of the pesticides. These mechanisms limit pesticide movement beyond the soil profile, highlighting the potential of cover crops to mitigate pesticide transfer to groundwater and other environmental compartments. Furthermore, our results provide thresholds for both cover crop densities and pesticides influenced by cover crops: well-developed living cover crops 80 d after sowing with a biomass of more than 1 tDM ha−1 significantly reduced soil residue contents by at least 33 % for compounds with low to high water solubility (s⩽1400 mg L−1) and low to moderate soil mobility (Koc⩾160 mL g−1). In Wallonia, 30 % of the most frequently used active substances fall within these thresholds, mainly concerning potato, sugar beet and winter cereal crops. These results confirm previous results on individual compounds, individual cover crop type and individual soil compartment, while introducing thresholds for physicochemical properties associated with significant pesticide degradation.

The hypothesised mechanism of pesticide residue degradation by cover crop builds on existing literature. We considered that cover crops reduce pesticide leaching by altering soil water fluxes though evapotranspiration and by concentrating pesticides near the roots, thereby prolonging their residence in the microbiologically active rhizosphere where biodegradation is enhanced (Fig. 3). The observed reduction in pesticide soil content is likely to be driven by edaphic microorganisms, as cover crops promote biodegradation by stimulating native soil microbiota, rather than direct uptake by plants. Major limitations of this study include the lack of direct measurements of soil microbial biomass and activity, and the lack of systematic assessment of pesticide metabolites.

By acting directly in the soil where pesticides are applied and during the fallow period when leaching risks are highest, cover crops limit pesticide transfers to other environmental compartments, particularly groundwater. As pesticide degradation is carried out by diverse microbial communities, these results highlight the importance of maintaining biologically active soils. They also highlight the need to carefully consider the critical transition period between crop harvest and cover crop establishment, as reduced evapotranspiration can increase pesticide leaching before the cover crop is fully developed. This underlines the importance of sowing cover crops as soon as possible after harvest to maximise their impact on pesticide residues, as their effect only becomes apparent after a period of growth and adaptation.

All raw data are available in the Supplement.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-12-17-2026-supplement.

NV: Funding Acquisition, Conceptualization, Investigation (equal), Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Visualization, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review and Editing. IT: Investigation (equal), Writing – Review and Editing (supporting). AB: Formal Analysis (pesticide quantification), Writing – Review and Editing (supporting). YA: Supervision, Funding Acquisition, Conceptualization, Investigation (supporting), Writing – Review and Editing.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

The authors express their gratitude to the Baillet Latour Fund, the Belgian Province of Luxembourg and the CER Groupe for their financial support. They also thank Huges Falys and the UCLouvain University Farms for their time and for providing the soil for the experiment, as well as Marc Migon and the UCLouvain Plant Cultivation Facilities (SEFY) for their time and for providing greenhouse space. Additionally, they are grateful to Frédéric Brodkom and the UCLouvain Science and Technology Library for their time and resources in supporting the open-access article processing charges. Noé Vandevoorde would like to extend special thanks to Éric Vandevoorde for his assistance in managing the phytoweb.be database, Céline Chevalier for her graphic support, and Basile Herpigny, Océane Duluins, Philippe V. Baret, Pierre Bertin and Lionel Alletto for their helpful feedback on earlier versions of this paper. The authors also thank Eglantina Lopez Echartea, Abel Veloso and the other (anonymous) reviewers, as well as the editors, for their constructive feedback that improved the paper.

This research was financially supported by the Baillet Latour Fund, the Belgian Province of Luxembourg, the CER Groupe and the BST-ELI fund for Open-Access publication.

This paper was edited by Lisa Ciadamidaro and reviewed by Eglantina Lopez Echartea, Abel Veloso, and two anonymous referees.

Agnan, Y., Alletto, L., Boithias, L., Budzinski, H., Giuliano, S., Deswarte, C., and Pelletier, A.: Suivis pluriannuels des transferts verticaux de pesticides dans des sols de vallée alluviale en monoculture de maïs irriguée [Multi-year monitoring of vertical pesticide transfer in irrigated maize monoculture soils in alluvial valley], in: 49e congrès du Groupe Français de Recherche sur les Pesticides, Montpellier, France, https://biogeoscience.eu/Files/Other/conferences/2019_Agnan_et_al_GFP.pdf (last access: 1 March 2025), 2019. a, b, c, d, e, f

Alletto, L.: Dynamique de l'eau et dissipation de l'isoxaflutole et du dicétonitrile en monoculture de maïs irrigué : effets du mode de travail du sol et de gestion de l'interculture [Water dynamics and dissipation of isoxaflutole and dicetonitrile in irrigated maize monoculture: effects of tillage method and intercrop management], Ph.D. thesis, INAPG, AgroParisTech, Paris, France, https://pastel.hal.science/pastel-00003244 (last access: 1 March 2025), 2007. a

Alletto, L., Benoit, P., Justes, E., and Coquet, Y.: Tillage and fallow period management effects on the fate of the herbicide isoxaflutole in an irrigated continuous-maize field, Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 153, 40–49, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2012.03.002, 2012. a, b

Alliot, C., Mc Adams-Marin, D., Borniotto, D., and Baret, P. V.: The social costs of pesticide use in France, Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 6, https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022.1027583, 2022. a

Bedos, C., Cellier, P., Calvet, R., Barriuso, E., and Gabrielle, B.: Mass transfer of pesticides into the atmosphere by volatilization from soils and plants: overview, Agronomie, 22, 21–33, https://doi.org/10.1051/agro:2001003, 2002. a

Blanco-Canqui, H., Ruis, S. J., Koehler-Cole, K., Elmore, R. W., Francis, C. A., Shapiro, C. A., Proctor, C. A., and Ferguson, R. B.: Cover crops and soil health in rainfed and irrigated corn: What did we learn after 8 years?, Soil Science Society of America Journal, 87, 1174–1190, https://doi.org/10.1002/saj2.20566, 2023. a

Bottomley, P. J., Sawyer, T. E., Boersma, L., Dick, R. P., and Hemphill, D. D.: Winter cover crop enhances 2,4-D mineralization potential of surface and subsurface soil, Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 31, 849–857, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0038-0717(98)00184-9, 1999. a

Bourguet, D. and Guillemaud, T.: The Hidden and External Costs of Pesticide Use, in: Sustainable Agriculture Reviews, vol. 19, edited by: Lichtfouse, E., Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland, 35–120, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-26777-7_2, 2016. a

Burtscher-Schaden, H., Clausing, P., Lyssimachou, A., and Roynel, S.: TFA: A Forever Chemical in the Water We Drink, Tech. rep., GLOBAL 2000, PAN Germany, PAN Europe, Vienna, Austria, https://www.pan-europe.info/sites/pan-europe.info/files/public/resources/reports/Report_TFA_The%20Forever%20Chemical%20%20in%20the%20Water%20We%20Drink.pdf (last access: 1 March 2025), 2024. a

Calvet, R., Barriuso, E., Bedos, C., Benoit, P., Charnay, M.-P., and Coquet, Y.: Les pesticides dans le sol: conséquences agronomiques et environnementales [Pesticides in the soil: agronomic and environmental consequences], France agricole éditions, Paris, France, ISBN 2-85557-119-7, https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-02834096v1 (last access: 1 March 2025), 2005. a

Cassigneul, A., Alletto, L., Benoit, P., Bergheaud, V., Etiévant, V., Dumény, V., Le Gac, A. L., Chuette, D., Rumpel, C., and Justes, E.: Nature and decomposition degree of cover crops influence pesticide sorption: Quantification and modelling, Chemosphere, 119, 1007–1014, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.08.082, 2015. a

Cassigneul, A., Benoit, P., Bergheaud, V., Dumeny, V., Etiévant, V., Goubard, Y., Maylin, A., Justes, E., and Alletto, L.: Fate of glyphosate and degradates in cover crop residues and underlying soil: A laboratory study, Science of The Total Environment, 545–546, 582–590, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.12.052, 2016. a

Chaplin-Kramer, R., O'Rourke, M., Schellhorn, N., Zhang, W., Robinson, B. E., Gratton, C., Rosenheim, J. A., Tscharntke, T., and Karp, D. S.: Measuring What Matters: Actionable Information for Conservation Biocontrol in Multifunctional Landscapes, Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 3, https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2019.00060, 2019. a

Chowdhury, A., Pradhan, S., Saha, M., and Sanyal, N.: Impact of pesticides on soil microbiological parameters and possible bioremediation strategies, Indian Journal of Microbiology, 48, 114–127, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12088-008-0011-8, 2008. a

Chuluun, B., Iamchaturapatr, J., and Rhee, J. S.: Phytoremediation of Organophosphorus and Organochlorine Pesticides by Acorus gramineus, Environmental Engineering Research, 14, 226–236, https://doi.org/10.4491/eer.2009.14.4.226, 2009. a

Cooper, J. and Dobson, H.: The benefits of pesticides to mankind and the environment, Crop Protection, 26, 1337–1348, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2007.03.022, 2007. a

Corder: Estimation quantitative des utilisations de produits phytopharmaceutiques par les différents secteurs d'activité [Quantitative estimate of the use of plant protection products by different sectors of activity], Annual repport CSC 03.09.00-21-3261, Public Services of Wallonia, SPW (ARNE-DEMNA & DEE), Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, https://www.corder.be/sites/default/files/2024-02/estimation-quantitative-des-utilisations-de-ppp-par-les-differents-secteurs-d%27activite.pdf (last access: 1 March 2025), 2023. a

Cycoń, M., Mrozik, A., and Piotrowska-Seget, Z.: Bioaugmentation as a strategy for the remediation of pesticide-polluted soil: A review, Chemosphere, 172, 52–71, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.12.129, 2017. a, b, c, d

Dabney, S. M., Delgado, J. A., and Reeves, D. W.: Using Winter Cover Crops to Improve Soil and Water Quality, Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis, 32, 1221–1250, https://doi.org/10.1081/CSS-100104110, 2001. a

Damalas, C. A. and Koutroubas, S. D.: Farmers' Exposure to Pesticides: Toxicity Types and Ways of Prevention, Toxics, 4, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics4010001, 2016. a

Das, R., Das, S. J., and Das, A. C.: Effect of synthetic pyrethroid insecticides on N2-fixation and its mineralization in tea soil, European Journal of Soil Biology, 74, 9–15, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejsobi.2016.02.005, 2016. a

de Albuquerque, F. P., de Oliveira, J. L., Moschini-Carlos, V., and Fraceto, L. F.: An overview of the potential impacts of atrazine in aquatic environments: Perspectives for tailored solutions based on nanotechnology, Science of The Total Environment, 700, 134868, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134868, 2020. a