the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Comparative impact of bio-organic and inorganic fertilizer application on soil health, grain quality and yield stability in nutrient deficient regions

Azhar Hussain

Asma Sabir

Eman Alhomaidi

Maqshoof Ahmad

Soil fertility limitations in arid regions restrict wheat productivity and grain nutritional quality, with zinc (Zn) deficiency being a major concern. Sustainable soil amendments combining organic and microbial inputs offer potential to address these constraints. This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of bio-organic fertilization in enhancing wheat growth, yield, grain Zn biofortification, and soil fertility under deficient arid field conditions. Two field trials were conducted in Bahawalpur and Bahawalnagar, Pakistan, using a randomized complete block design. Treatments included compost, ZnO (2 %), ZnSO4, zinc-solubilizing bacteria (ZSB), and their combinations. Wheat growth, yield, grain nutrient concentrations, and soil fertility indicators (organic matter, microbial biomass nitrogen (MBN), microbial biomass carbon (MBC), and nutrient availability) were measured. Microbial populations were determined through colony-forming units. Correlation and principal component analysis (PCA) were applied to explore associations among variables. The integrated application of compost + ZnO + ZSB significantly improved wheat height (19 %), biomass (20 %), yield attributes (10 %), and grain Zn concentration (39 %) compared with the control. Soil fertility parameters also increased (organic matter, 39%; MBN, 32%; MBC, 27 %). Correlation and PCA highlighted strong positive relationships among microbial populations, soil fertility, and crop performance. Bio-organic fertilization provides an eco-friendly and effective strategy to improve wheat yield, Zn biofortification, and soil fertility in arid agroecosystems.

- Article

(1448 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Soil fertility degradation and micronutrient deficiency, particularly of zinc (Zn), are increasingly critical concerns in arid and semi-arid agroecosystems, where climatic stressors and anthropogenic pressures have exacerbated soil quality (Lal, 2024). In these fragile environments, characterized by low organic matter, poor water retention, and nutrient depletion, the production of staple crops, such as wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), is consistently threatened (Hossain et al., 2021). Zinc deficiency is among the most widespread micronutrient disorders affecting cereal crops globally, with particularly high prevalence in calcareous and coarse-textured soils typical of arid zones (Dhaliwal et al., 2022). It is estimated that over 50 % of soils cultivated for cereals in arid and semi-arid regions suffer from Zn insufficiency, which not only reduces crop productivity but also compromises grain Zn concentration, a factor that directly affects human nutrition in regions where wheat is a dietary staple (Younas et al., 2023).

To address such multifaceted challenges, integrated soil fertility management approaches have emerged, combining organic and inorganic strategies to enhance soil health, crop productivity, and environmental sustainability (Imran, 2024). Among these, composting has garnered attention due to its capacity to recycle organic waste into a valuable soil amendment that can improve physical structure, chemical fertility, and biological activity (Sharma et al., 2024). Compost application increases soil organic carbon (SOC), stabilizes soil aggregates, enhances microbial biomass carbon (MBC) and microbial biomass nitrogen (MBN), and provides a slow-release source of macro- and micronutrients (Khan et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2025). However, standard composts are often limited in their ability to address specific micronutrient deficiencies such as Zn, particularly in soils with high pH, where Zn becomes poorly available to plants due to adsorption and precipitation processes (Qian et al., 2023).

In this context, the concept of “bioactivation” of compost, which involves enriching compost with bioavailable forms of essential nutrients such as zinc (Zn), along with the inclusion of beneficial microorganisms, represents an innovative and promising solution (Manea and Bumbac, 2024). Bioactivated compost not only supplies nutrients but also enhances microbial functions, potentially improving nutrient cycling, enhancing soil enzymatic activity, and mitigating abiotic stress in plants (Clagnan et al., 2023). The microbial solubilization of Zn compounds, for example, through the action of zinc-solubilizing bacteria (ZSB), can significantly increase the bioavailability of Zn in the rhizosphere, promoting better root development and nutrient uptake (Singh et al., 2024). When applied to nutrient-deficient arid soils, bioactivated Zn-enriched compost may thus serve as a multifaceted amendment to restore soil fertility, stimulate microbial activity, and ultimately improve crop yield and quality (Maitra et al., 2024).

Despite its potential, the use of bioactivated Zn-enriched compost in arid regions remains underexplored, particularly in terms of its comparative effects on key soil health indicators such as organic matter content, SOC, MBC, MBN, and plant-available nutrients. Moreover, understanding the interaction between compost-borne microbial communities and Zn dynamics in the soil–plant system is essential for optimizing compost formulations and application strategies (Wang et al., 2024). The wheat crop, as a high-input cereal with substantial nutrient demand, serves as an ideal model for evaluating the effectiveness of such integrated nutrient management approaches under stress-prone environmental conditions.

Despite increasing interest in Zn-enriched organic amendments, most available studies have focused on humid or semi-controlled environments (Waterlot et al., 2024), while evidence from arid and semi-arid regions remains limited (Feliziani et al., 2025). High soil pH, low organic matter, and rapid micronutrient fixation pose unique challenges in these systems, often reducing the effectiveness of conventional Zn fertilizers (Sethi et al., 2025). Consequently, field-based evaluations of bioactivated Zn-enriched compost under arid conditions are still scarce, highlighting the need for location-specific validation (Sreenivasa, 2011; Prasath et al., 2018). Addressing these gaps is critical for developing scalable, cost-effective, and environmentally sustainable zinc management strategies for nutrient-deficient regions.

Recently, our research group reported the development of a bio-activated Zn-enriched compost from organic waste and its application in a field experiment on wheat in Zn-deficient soils (Naeem et al., 2025), where significant improvements in soil biochemical properties, Zn availability and wheat grain yield were observed. However, these experiments were conducted under closely monitored research-managed conditions, which may not fully reflect the variability and constraints of farmer-managed arid agroecosystems. The present study advances this earlier work by validating the performance of microbial-assisted Zn-enriched compost across two distinct farmer-field locations under real agronomic practices. This multi-location, field-scale assessment integrates soil biochemical indicators, crop productivity, grain Zn biofortification, and economic returns, thereby providing new insights into the scalability, adaptability, and on-farm feasibility of bio-organic Zn management strategies in nutrient-deficient arid soils.

Specifically, the research aims to: assess changes in soil organic matter, SOC, macro- and micronutrient content, microbial biomass carbon (MBC), and microbial biomass nitrogen (MBN) following compost application; determine the effectiveness of Zn enrichment and microbial activation in enhancing Zn availability and uptake; and quantify the response of wheat growth, yield, and Zn content under field conditions typical of arid agroecosystems. The working hypothesis is that microbial-assisted Zn-enriched compost leads to significant improvements in soil fertility and microbial health, resulting in higher wheat productivity and nutritional quality compared to conventional practices.

From an environmental perspective, the utilization of compost, particularly when derived from agricultural, municipal, or agro-industrial residues, contributes to sustainable waste management by diverting organic matter from landfills and mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. Composting stabilizes organic residues, reducing methane generation and leachate formation, while also sequestering carbon in soils – an important consideration in climate change mitigation. Furthermore, the inclusion of beneficial microbes and micronutrient enrichment in compost contributes to soil biodiversity and resilience, supporting the ecological functions that underpin sustainable

2.1 Compost Preparation

To prepare zinc-enriched compost from domestic organic waste (Fruit and vegetable waste), a systematic approach comprising composting, zinc fortification, and microbial bioactivation was used. Initially, segregated domestic organic waste (vegetable peels, fruit residues, kitchen scraps) is collected and pre-processed by shredding to reduce particle size for faster decomposition. A composting drum was used, where the organic material was layered with urea (1 % ) to speed up the composting process. Moisture is maintained at 40 %–50 %, and the pile is turned periodically to ensure aerobic conditions. After the thermophilic phase (21 d), during the mesophilic stage, zinc was introduced in the form of zinc oxide (ZnO) at a predetermined concentration (2 % ). This timing ensures optimal microbial assimilation and mineral retention within the compost matrix. The composting continues for 28 d until maturation, characterized by a dark brown color and crumbly texture. For bioactivation, a microbial consortium of Zinc solubilizing bacteria (ZSB) is prepared by culturing strains such as Bacillus subtilis (IUB2; accession no. MN696212 and IUB6; accession no. MN696214), Bacillus velezensis (IUB3; accession no. MN696213), Bacillus vallismortis (IUB10; accession no. MN696215) and Bacillus megaterium (IUB11; accession no. MN696216) in a nutrient broth for 24–48 h at 28–30 °C until reaching an optical density of 0.8–1.0 at 600 nm. The mature compost is inoculated with the ZSB consortium (0.1 % ) by spraying the bacterial suspension uniformly over the compost during final turning. Moisture is adjusted to around 40 % to support microbial activity, and the compost is incubated for an additional 2 d under shaded conditions to stabilize the bioactivation process. The final microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost is then dried, sieved, and stored for agronomic use. This dual enrichment process enhances the compost's micronutrient content and microbial efficiency for sustainable soil fertility management.

The bacterial strains used in the present study had already been characterized for zinc and phosphorus solubilization, catalase and urease activity, exopolysaccharide, siderophore and indole 3 acetic acid production and plant growth promotion (Naseem et al., 2022). The elevated levels of nitrogen (3.36 %), phosphorus (23 mg kg−1), potassium (221 mg kg−1), iron (12.43 mg kg−1) and zinc (23.14 mg kg−1) observed in the Zn-enriched compost, as compared to the unenriched compost, are primarily due to incorporation of nutrient-rich materials during the enrichment procedure. Zinc oxide was added, and beneficial rhizobacteria were introduced to enhance the solubilization and availability of nutrients. The increased Zn and Fe concentrations are a direct result of these inputs, while the rise in N, P and K levels can be attributed to enhanced microbial activity. This microbial stimulation promotes the decomposition of organic matter and accelerates nutrient cycling. Additionally, the introduced microbes contribute by mobilizing phosphorus and micronutrients through the secretion of organic acids and chelating agents. As a result, the enrichment process not only enhances the compost's nutrient content but also improves its microbial efficacy, resulting in improved nutrient availability.

2.2 Field trial

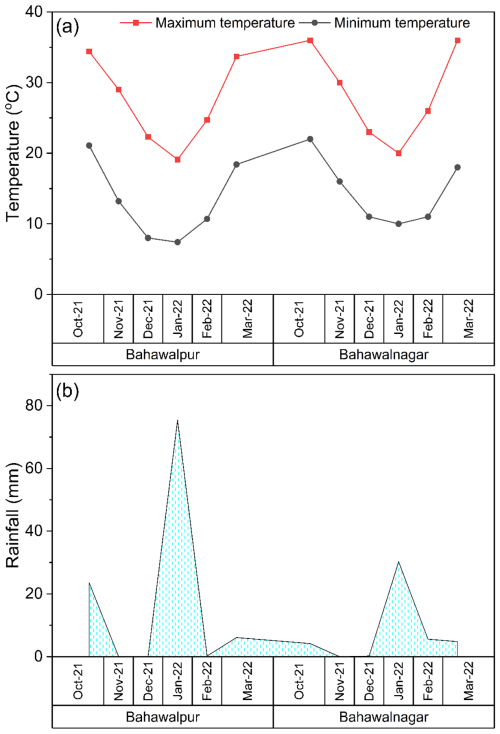

Two field experiments were conducted at separate arid locations, Bahawalpur (29.3544° N, 71.6911° E) and Bahawalnagar (29.1903° N, 72.6343° E), to evaluate the effects of ten (10) different treatments on crop performance. The weather data, including monthly average temperature and rainfall (mm) during the cropping season (2021–2022), were presented in Fig. 1. The treatments included the sole and combined application of a market source of zinc (ZnSO4), a cheap source of zinc (ZnO), compost, zinc solubilizing rhizobacteria, and microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost. The experiment consists of ten treatments; T0: Control; T1: ZnSO4; T2: ZnO; T3: Compost; T4: ZSB; T5: compost + 2 % ZnO; T6: ZnSO4+ ZSB; T7: ZnO + ZSB; T8: compost + ZSB; T9: compost + 2 % ZnO + ZSB (microbial-assisted Zn-enriched compost). A randomized complete block design (RCBD) was used with three replications per treatment at each site to ensure statistical reliability. The control treatment (T0) represents the prevailing farmers' field practice in the study area, where recommended doses of N, P, and K fertilizers are applied without supplemental zinc or organic amendments. This treatment, therefore, reflects the actual baseline production system commonly adopted by farmers in arid regions.

Figure 1Climate data from experimental sites during the 2021–2022 cropping season. Data is presented as the monthly average temperature (a) and total rainfall (mm) in a month (b).

Before sowing, composite soil samples were collected from the 0–15 cm depth across each site and analyzed for baseline fertility status. The soils at both locations were characterized as deficient arid soils with the average properties: pH (7.69 and 8.1), electrical conductivity (EC) (1.27 and 1.42 dS m−1), organic matter (0.43 % and 0.51 %), total nitrogen (0.032 % and 0.035 %), available phosphorus (8.8 and 9.8 mg kg−1), available potassium (73 and 85 mg kg−1), DTPA-extracted zinc (0.63 and 0.71 mg kg−1) and DTPA extracted iron (0.56 and 0.51 mg kg−1) in trial I (Bahawalpur) and II (Bahawalnagar), respectively. Based on soil test results and crop nutrient requirements, recommended doses of fertilizers (e.g., 120 kg of N ha−1, 90 kg of P ha−1, and 60 kg of K ha−1) were applied. Phosphorus and potassium were incorporated at the time of seedbed preparation using diammonium phosphate (DAP) and sulfate of potash (SOP), respectively, while nitrogen was split-applied: one-third as a basal dose using urea at sowing, and the remaining two-thirds in two equal splits at tiller formation and early flowering stages to minimize losses and enhance nutrient use efficiency. A basal dose of ZnSO4 (33 % Zn) and microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost were applied @ 12 and 250 kg ha−1, respectively. Chemical fertilizer application was reduced by 5 % in the treatment where Microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost was used. All agronomic practices were kept uniform across treatments.

2.3 Soil and plant samples collection and analysis

The growth parameters, such as plant height, number of tillers and biomass, were recorded at harvest. Yield attributes, including 1000-grain weight, grain yield per hectare, and harvest index, were measured post-harvest. For nutrient analysis, plant tissues (e.g., grain) were collected at harvest, dried, ground, and analyzed for macro- and micronutrient content using standard procedures. Rhizosphere soil samples were carefully collected at harvest by gently shaking the soil adhered to the root zone, then analyzed for microbial population (CFU g−1 soil), total organic carbon, available NPK, DTPA extracted Fe and Zn, and microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen.

2.4 Plant analysis

The determination of nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) in grain samples was conducted using a wet digestion method involving sulfuric acid (H2SO4) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Oven-dried grain samples (0.5 g) were placed in digestion tubes and initially treated with concentrated H2SO4 (6 mL) to break down organic matter. Hydrogen peroxide (2 mL) was added dropwise to enhance oxidation and complete the digestion. The mixture was heated until the solution became clear, indicating complete digestion. The digested samples were allowed to cool, diluted with distilled water, and filtered. The clear filtrate was analyzed for total N using the Kjeldahl method, P content was determined colorimetrically using the molybdenum blue method, and K was quantified using a flame photometer. This method ensures efficient mineralization of organic components and accurate estimation of macronutrients essential for grain quality assessment (Ryan et al., 2001).

The analysis of zinc (Zn) and iron (Fe) concentrations in grain samples was conducted using the diacid digestion method, employing a mixture of nitric acid (HNO3) and perchloric acid (HClO4). Oven-dried and ground grain sample (0.5 g) was accurately weighed into a digestion flask. A 10 mL aliquot of concentrated HNO3 was added, and the mixture was allowed to pre-digest overnight at room temperature to initiate breakdown of organic matter. The following day, 4 mL of concentrated HClO4 was added, and the sample was subjected to controlled heating on a digestion block, gradually increasing the temperature up to 350 °C until white fumes appeared, indicating the completion of organic matrix oxidation. The digestion was continued until a clear solution was obtained. After cooling, the digested sample was diluted with deionized water and filtered. The final volume was made up to a known volume (50 mL) with deionized water. The concentrations of Zn and Fe in the digest were then determined using an atomic absorption spectrophotometer (AAS). All glassware was acid-washed to minimize contamination, and analytical-grade reagents were used throughout the procedure. The instrument was standardized by using respective standard solutions of Fe and Zn (Antreich, 2012).

2.5 Soil chemical analysis

For the soil biochemical analysis, soil samples were systematically collected from designated study sites using a clean stainless-steel auger to minimize contamination. Samples were air-dried, sieved through a 2 mm mesh to remove debris and stones, and stored in polythene bags for laboratory analysis. Chemical properties were assessed by measuring soil organic matter content through the Walkley-Black method (Jha et al., 2014). Available nutrients, including nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K), were quantified using Kjeldahl digestion for N (Estefan et al., 2013), Olsen methods for P (Olsen, 1954), and flame photometry for K after ammonium acetate extraction (Shuman and Duncan, 1990).

2.6 Soil biochemical analysis

For the analysis of soil microbial biomass carbon (MBC) and microbial biomass nitrogen (MBN), soil samples were collected from the study area and air-dried before sieving through a 2 mm mesh. The fumigation-extraction method was employed, where one set of samples was fumigated with chloroform vapor for 24 h to lyse microbial cells, while the other set served as non-fumigated controls (Brookes et al., 1985). Following fumigation, both sets were extracted with 0.5 M K2SO4 solution, and the extracts were analyzed for dissolved organic carbon and nitrogen using a total organic carbon analysis and the Kjeldahl method, respectively. Microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen were calculated by subtracting the values of non-fumigated samples from fumigated ones. All analyses were conducted in triplicate to ensure accuracy and reproducibility, and standard quality control procedures were followed throughout the process.

For the analysis of soil ammonium (NH) and nitrate (NO) nitrogen, soil extracts were prepared by shaking 10 g of soil with 100 mL of 2 M potassium chloride (KCl) solution for 30 min to displace exchangeable ammonium and nitrate ions. The suspension was then filtered through a Whatman No. 42 filter paper. Ammonium nitrogen concentration in the filtrate was determined colorimetrically using the indophenol blue method, while nitrate nitrogen was measured by the phenol disulfonic acid method and readings were taken on UV spectrophotometer at 220 nm (Kachurina et al., 2000). All analyses were performed in triplicate to ensure accuracy, and results were expressed in mg kg−1 of soil. Quality control included calibration curves using standard NH and NO solutions, reagent blanks, and periodic checks with known reference materials.

2.7 Economic analysis

The economic analysis was estimated, and subsequently, the costs and returns of various items used in this study for wheat cultivation, as normally practiced by farmers (control), and the application of a market source of zinc and microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost (Khan et al., 2012) were apportioned. Gross margin was calculated by the following formula to make comparisons.

Economic comparisons were made using the control treatment as a benchmark representing farmers' conventional fertilization practices. This approach ensures that profitability assessments realistically reflect on-farm decision-making conditions rather than idealized experimental scenarios.

2.8 Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis in this study was conducted using a combination of multivariate techniques. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was employed to test for significant differences between group means. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was done to reduce dimensionality and identify the gradients of variation in the dataset, facilitating visualization of patterns and clustering. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to quantify the strength and direction of linear associations between pairs of continuous variables. All analyses were performed using OriginPro 2021b and Statistix 8.1 software, with significance levels set at α= 0.05.

The results from both field trials consistently demonstrated the positive role of microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost in improving wheat growth, nutrient accumulation, and soil health. Treatments integrating compost, zinc sources, and zinc-solubilizing bacteria (ZSB) performed better than sole or dual applications, highlighting the synergistic effect of organic matter and microbial activity. The results demonstrated the influence of microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost on plant performance, grain nutritional quality, and soil fertility parameters.

3.1 Comparative effect of bio-organic and organic fertilizers on soil biochemical properties

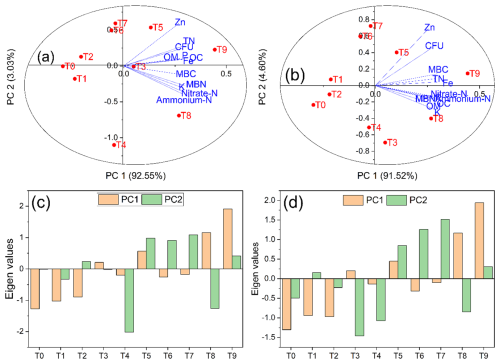

In both Trial I (Bahawalpur) and Trial II (Bahawalnagar), the application of microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost significantly improved soil fertility parameters compared to the control and sole application of inorganic fertilizer (Table 1). The highest enhancement in organic matter (OM), total organic carbon (TOC), and macro- and micronutrient contents (N, P, K, Fe, and Zn) was observed in the treatment combining compost with 2 % ZnO and zinc-solubilizing bacteria (ZSB). In Trial I, the treatment Compost + 2 % ZnO + ZSB (T9) resulted in a remarkable increase in soil OM and TOC by 38.6 % over the control. Nitrogen (N) content increased by 17.1 %, phosphorus (P) by 23.2 %, and potassium (K) by 17.9 %. Micronutrient concentrations were also significantly enhanced, with iron (Fe) increasing by 22.6 % and zinc (Zn) by an impressive 22.0 % relative to the control. Similarly, in Trial II, the same treatment (Compost + 2 % ZnO + ZSB) demonstrated the most effective results, improving OM by 38.3 %, TOC by 31.8 %, N by 20.4 %, P by 20.2 %, and K by 22.0%. Increases in Fe and Zn were recorded at 25.8 % and 20.6 %, respectively, compared to untreated soil.

Table 1Effect of Microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost on soil biochemical properties.

Data is presented as mean of three replicates ± standard error. Means sharing same letter(s) within a column are statistically non-significant at 5 % probability. * P<0.05; P<0.01; P<0.001; P<0.0001;

ns: non-significant

In Trial I, the treatment (compost + 2 % ZnO + ZSB) led to a maximum CFU count (34.1 × 106 CFU g−1 soil), showing an increase of 50.3 % over the control. Microbial biomass carbon (MBC) and microbial biomass nitrogen (MBN) were significantly elevated, with increases of 21 % and 26 %, respectively, compared to the untreated control. Additionally, ammonium-N and nitrate-N concentrations increased by 25 % and 23 %, respectively. Similarly, in Trial II, the Compost + 2 % ZnO + ZSB treatment again resulted in the highest values, with CFU increasing by 39%, MBC by 27 %, MBN by 32 %, ammonium-N by 28.2 %, and nitrate-N by 27.7 % relative to the control.

Among individual and dual component treatments, Compost + ZSB and compost + 2 % ZnO showed superior performance compared to sole applications. Compost + ZSB increased MBC by 16 % in Trial I and 22 % in Trial II, whereas compost + 2 % ZnO enhanced nitrate-N by 12 % in both trials. The integration of compost, zinc (in the form of ZnO), and zinc-solubilizing bacteria (ZSB) synergistically improved soil biochemical properties, underscoring the potential of microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost as a sustainable soil amendment in enhancing soil fertility and microbial function.

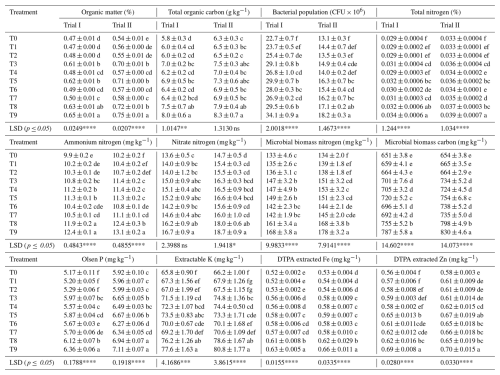

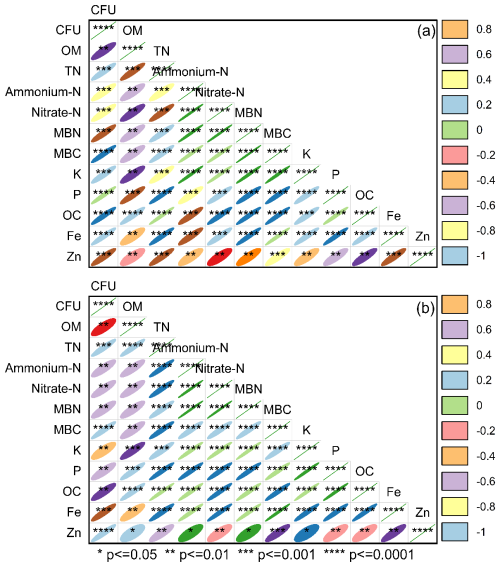

3.2 Multivariate analysis of the studied parameters compares the effectiveness of bio-organic and inorganic fertilizers to improve soil health

The significance of the results was further confirmed through multivariate analysis. Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed clear separation among treatments, indicating distinct influences of different zinc and organic amendments on soil biochemical properties (Fig. 2). In trial I, the two principal components (PC1 and PC2) accounted for 95.58 % of the total variance, with PC1 alone contributing 92.55 %. Treatments involving combinations of compost and zinc sources, especially Compost + 2 % ZnO + ZSB and Compost + ZSB, were closely associated with higher scores on PC1, primarily driven by elevated levels of soil organic matter (OM), total organic carbon (TOC), nitrogen (N), and available phosphorus (P). These treatments clustered in the positive quadrant of the biplot, indicating strong synergistic effects on soil fertility indicators. On the other hand, the control and mineral ZnSO4-alone treatment showed negative associations with PC1 and PC2, reflecting minimal improvements in soil nutrient status. Zinc oxide in combination with ZSB (ZnO + ZSB) showed a moderate effect, clustering near the origin, suggesting limited but positive contributions to zinc availability and other nutrients.

Figure 2Principal component analysis (PCA) demonstrates the effectiveness of microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost to improve soil biochemical properties. (a) PCA – trial I (Bahawalpur); (b) PCA – trial II (Bahawalnagar); (c) eigenvalues – trial I; (d) eigenvalues – trial II; Zn: DTPA-extracted zinc; TN: total nitrogen; CFU: colony forming units; OM: organic matter; TOC: total organic carbon; MBC: microbial biomass carbon; MBN: microbial biomass nitrogen; Fe: DTPA extracted iron; P: Olsen phosphorous; K: extractable potassium.

In Trial II, PCA highlighted similar patterns with the two principal components explaining 96.12 % of the total variance, where PC1 accounted for 91.52 % and PC2 for 4.60 %. Compost-based treatments again formed a distinct cluster, particularly Compost + 2 % ZnO + ZSB and Compost + ZSB, indicating their significant influence on soil OM, TOC, and micronutrient (Fe and Zn) concentrations. Control and ZnSO4 alone consistently showed the lowest contributions across both principal components, reinforcing their limited efficacy in improving soil fertility. Overall, the PCA confirmed that treatments integrating organic matter (compost) and biological agents (ZSB) with zinc sources (ZnO) led to more comprehensive improvements in soil nutrient status compared to inorganic treatments.

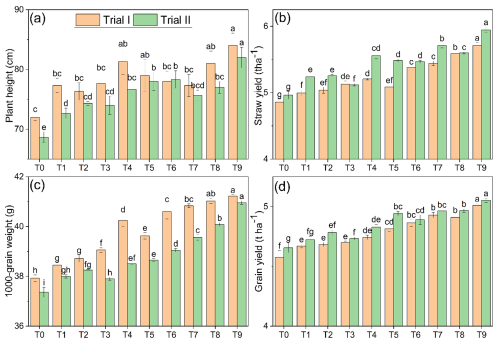

3.3 Effectiveness of bio-organic fertilizer to improve plant growth and yield

In both Trial I (Bahawalpur) and Trial II (Bahawalnagar), the application of microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost demonstrated a significant improvement in wheat growth, particularly in terms of plant height, shoot dry biomass, 1000-grain weight and grain yield (Fig. 3). Among the treatments, the combined application of Compost + 2 % ZnO + ZSB (T9) yielded the most pronounced effects. In Trial I, the Compost + 2 % ZnO + ZSB treatment increased plant height by 16.7 % and shoot dry biomass by 17.6 % compared to the control. Similarly, in Trial II, this treatment resulted in a 19.4 % increase in plant height and a 19.8 % increase in shoot dry biomass over the control. The next most effective treatments were Compost + ZSB (T8) and Compost + ZnO (T5). Compost + ZSB enhanced plant height by 12.5 % and 12.1 % and shoot biomass by 15.1 % and 12.8 % in Trials I and II, respectively. Compost + ZnO led to increases of 9.7 % and 13.6 % in plant height, and 4.7 % and 10.5 % in biomass for Trials I and II, respectively.

Figure 3Effect of microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost on the growth and yield of wheat. The same letter(s) on the bars represent statistically non-significant variation at 5 % probability (n= 3, p≤ 0.05). Trial I: Bahawalpur; Trial II: Bahawalnagr; (a) plant height; (b) straw yield; (c) 1000-grain weight; (d) grain yield.

In Trial I, the highest 1000-grain weight was recorded in the compost + 2 % ZnO + ZSB (T9) treatment, showing an 8.7 % increase over the control. This was followed by compost + ZSB (8.2 %) and ZnO + ZSB (7.7 %). In terms of grain yield per hectare, the compost + 2 % ZnO + ZSB treatment led to a significant 9.5 % increase compared to the control. Other notable increases in yield included compost + ZSB (7.3 %), ZnSO4+ ZSB (6.3 %), and ZnO + ZSB (7.7 %). Trial II confirmed the trends observed in Trial I. The compost + 2 % ZnO + ZSB treatment again yielded the highest 1000-grain weight, with a 9.6 % increase over the control. Compost + ZSB and ZnSO4+ ZSB treatments improved 1000-grain weight by 7.3 % and 5.9 %, respectively. Grain yield was similarly enhanced, with the compost + 2 % ZnO + ZSB treatment resulting in a 8.5 % increase over the control. The compost + ZSB (6.7 %), ZnSO4+ ZSB (5.0 %), and ZnO + ZSB (6.6 %) treatments also showed considerable improvements.

In contrast, sole applications of ZnO, ZnSO4, or compost alone had moderate effects on both parameters, with increases ranging between 1 %–3 % depending on the trial and variable measured. The ZSB treatment alone showed a limited but positive effect, suggesting that microbial inoculants are more effective when combined with zinc sources and organic amendments.

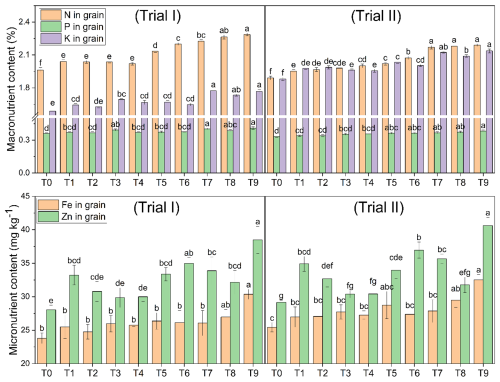

3.4 Comparative improvement in grain quality by the application of bioorganic and inorganic fertilizers

Based on the results obtained from both Trial I (Bahawalpur) and Trial II (Bahawalnagar), the application of microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost significantly improved the concentration of macronutrients (N, P, K) and micronutrients (Fe and Zn) in wheat grains compared to the control and individual application of inorganic fertilizers (Fig. 4). In Trial I, the combined treatment of Compost + 2 % ZnO + ZSB (T9) demonstrated the highest nutrient enhancement across all measured parameters. This treatment led to an increase of 16.5 % in nitrogen (N), 13.9 % in phosphorus (P), and 11.3 % in potassium (K) contents compared to the control. In terms of micronutrients, grain iron (Fe) content (30.4 mg kg−1) and zinc (Zn) content (38.5 mg kg−1) were recorded, which were increased by 27.6 % and 37.3 %, respectively, relative to the control. Similarly, in Trial II, the Compost + 2% ZnO + ZSB treatment consistently outperformed all other treatments. Compared to the control, it increased grain nitrogen by 15.9 %, phosphorus by 15.0 %, potassium by 13.7 %, iron by 27.9 %, and zinc by 39.4 %. The treatments ZnO + ZSB and ZnSO4+ ZSB also showed considerable improvements over the sole applications of ZnO or ZnSO4, suggesting the synergistic effect of zinc-solubilizing bacteria (ZSB) in mobilizing native and supplemented zinc sources.

Figure 4Effect of microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost on the macro- and micronutrient concentration in wheat grain. The same letter(s) on the bars represent statistically non-significant variation at 5 % probability (n= 3, p≤ 0.05). Trial I: Bahawalpur; Trial II: Bahawalnagar.

The Compost + ZSB treatment also enhanced nutrient accumulation in grains, albeit to a lesser extent than the Compost + 2 % ZnO + ZSB. Sole compost and ZSB treatments moderately increased nutrient content compared to the control, while the sole application of ZnSO4 and ZnO resulted in lower improvements than when these sources were bioactivated. Overall, the combined application of compost, ZnO, and ZSB (Compost + 2 % ZnO + ZSB) was the most effective strategy for promoting the biofortification of wheat grains with essential nutrients in both trials.

3.5 Correlation analysis demonstrates the interactive effect of improved soil fertility parameters on yield

Correlation analysis revealed significant positive relationships among soil biochemical parameters, bacterial population in term of colony forming units (CFU g−1 soil), microbial biomass carbon (MBC), and microbial biomass nitrogen (MBN) and key soil nutrients (N, P, K, Fe, and Zn) with crop yield (Fig. 5). Specifically, CFU exhibited a strong positive correlation with MBC (r= 0.82, p< 0.01) and MBN (r= 0.76, p<0.01), indicating that enhanced microbial abundance supports higher microbial biomass. MBC and MBN were significantly correlated with available nitrogen (r= 0.79 and 0.74, respectively; p< 0.01), suggesting active microbial involvement in nutrient mineralization and cycling. Available phosphorus and potassium were also positively correlated with microbial indicators (MBC–P: r= 0.68; MBN–K: r= 0.63; p< 0.05), underscoring the role of microbial processes in improving nutrient availability. Moreover, micronutrients such as Fe and Zn showed moderate but significant correlations with MBC (r= 0.59 and 0.57, respectively; p< 0.05), suggesting microbial-mediated enhancement of micronutrient solubility. Importantly, crop yield demonstrated strong positive correlations with MBC (r= 0.85), MBN (r= 0.80), and CFU (r= 0.78), as well as with macronutrients N (r= 0.83), P (r= 0.77), and K (r= 0.75). These findings collectively indicate that microbial activity and biomass are closely linked to nutrient availability and are reliable predictors of soil fertility and crop productivity.

Figure 5Pearson's correlation analysis was used to describe the relationship between the studied soil parameters. The thickness of the ellipses represents the correlation coefficient (R) and the asterisks represent the significance based on p-value. (a) Trial I (Bahawalpur); (b) Trial II (Bahawalnagar).

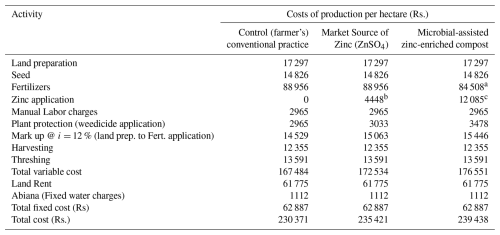

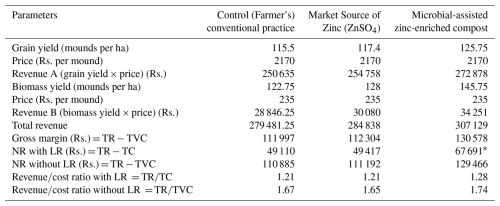

3.6 Comparison of bio-organic and inorganic (ZnSO4) fertilizers for cost of production and net returns for one hectare of wheat

In the study area, the total cost of cultivating one hectare of control (untreated), ZnSO4 (market source of zinc) and microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost (bio-organic fertilizer) of wheat comprised several components, including land preparation, sowing, seed, fertilizer application, plant protection (weedicide and pesticide), manual labor, irrigation, and harvesting and threshing operations (Table 2). The production cost per hectare was calculated as Rs. 230 371 for control wheat, Rs. 235 353 for ZnSO4-treated wheat, and Rs. 239 438 for the microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost-treated wheat. The treated wheat incurred higher costs than the control (untreated) wheat, mainly due to the application of zinc fertilizers. For wheat cultivation, the total production cost also accounted for opportunity costs, calculated as a 12 % markup from land preparation to fertilizer application. These amounted to Rs. 14 529 for control, Rs. 15 063 for ZnSO4, and Rs. 15 446 for the microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost. Manual labor costs were Rs. 2965, Rs. 3033, and Rs. 3478, respectively. As detailed in Table 3, the total cost (TC) was broken down into Total Variable Cost (TVC) and Total Fixed Cost (TFC). The TVC included expenses related to land preparation, seed, fertilizers, labor, markup, and harvesting and threshing. The estimated TVC per hectare was Rs. 167 484 for control, Rs. 172 534 for ZnSO4, and Rs. 176 551 for the microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost. TFC, on the other hand, included fixed expenses such as land rent and abiana (government water charges), which collectively amounted to Rs. 62 887 per hectare. Land rent was treated as an opportunity cost, as most farmers in the region owned their land. The total cost of production (TC) was derived by summing the TVC and TFC.

Table 2Comparison of the per-hectare cost of production of wheat treated as a control (no application of zinc), ZnSO4 and microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost.

The cost of production was calculated using the current rates of commodities in the local market. a Reduced application of chemical fertilizers by 5 %; b Price of ZnSO4; c Price of microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost.

Table 3Gross margin, net income and revenue to cost () ratio.

Yield is presented as average of both trials conducted in Bahawalpur and Bahawalnagar. * Significant increase in net income by the application of microbial-assisted zin-enriched compost.

The gross margin, net return, and revenue-to-cost () ratio were calculated for the cultivation of one hectare of wheat treated as control, ZnSO4, and microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost (Table 3). Based on Eq. (1), the gross margins were estimated at Rs. 111 997 for control, Rs. 112 304 for ZnSO4 and Rs. 130 578 for the microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost. Net returns were determined by deducting the total costs (TC) from total revenue (TR). When land rent (LR) was included, the net returns amounted to Rs. 49 110 for control, Rs. 49 417 for ZnSO4, and Rs. 67 691 for the microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost. Excluding land rent, the net returns increased to Rs. 110 885, Rs. 111 192, and Rs. 129 466, respectively. Likewise, the revenue-to-cost ratios, including land rent, were 1.21 for control and ZnSO4, and 1.28 for the microbial-assisted zin-enriched compost. Without considering land rent, these ratios improved to 1.67, 1.65, and 1.74, respectively. The similarity in revenue-to-cost ratios between the ZnSO4 treatment and the control reflects the limited economic benefit of conventional zinc fertilization under calcareous arid soils, where zinc fixation reduces plant availability. This outcome underscores the necessity of biologically assisted Zn delivery systems, which demonstrated superior profitability in the present study.

The results of both trials distinctly highlight the agronomic and soil-enhancing potential of bioorganic fertilizer, particularly when integrated with zinc oxide (ZnO) and zinc-solubilizing bacteria (ZSB). The treatment combination of Compost + 2 % ZnO + ZSB consistently outperformed all other treatments across all growth, yield, nutrient uptake, and soil fertility parameters. These findings underscore the efficacy of an integrated nutrient management approach combining organic, inorganic, and biological amendments in enhancing wheat productivity and soil health.

Soil chemical properties were significantly influenced by the bio-organic fertilizer application. The observed increase in zinc (Zn) availability can be attributed to two complementary mechanisms: the gradual and sustainable release of Zn from ZnO particles and the active microbial solubilization of Zn compounds facilitated by Zn-solubilizing bacteria (ZSB) (Huang et al., 2022). These processes ensure a continuous supply of bioavailable Zn, reducing the risk of nutrient fixation in soil. In addition, the enhanced availability of nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) is primarily linked to accelerated microbial mineralization of organic matter, enzymatic hydrolysis of complex organic compounds, and the decomposition of compost materials (Reimer et al., 2023). Collectively, these mechanisms enhance soil nutrient cycling and ensure the synchronized release of nutrients that match plant demand.

Biological indicators of soil fertility, including colony-forming units (CFU), microbial biomass carbon (MBC), and microbial biomass nitrogen (MBN), were improved by the Compost + 2 % ZnO + ZSB treatment. This demonstrates not only the proliferative effect of compost as a microbial substrate but also the synergistic interactions between microbial inoculants and native soil microbiota, which enhance microbial colonization and community stability (Dincă et al., 2022; Lu et al., 2025). ZSB plays a critical mechanistic role by releasing organic acids (Sethi et al., 2025), siderophores (Zhu et al., 2025), and hydrolytic enzymes that mobilize nutrients (Mujumdar et al., 2024), improve rhizosphere activity, and stimulate beneficial plant–microbe interactions (Jalal et al., 2024; Feng et al., 2024). Furthermore, the observed increases in nitrate-N and ammonium-N concentrations indicate enhanced nitrogen transformation pathways, including ammonification, nitrification, and mineralization processes, actively mediated by microbial communities (Duan et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2025). These transformations improve nitrogen turnover and ensure steady nutrient availability to crops, thereby supporting higher productivity and nutrient use efficiency.

The pronounced improvement in soil biochemical properties under the integrated application of compost + ZnO + ZSB can be attributed to synergistic interactions between organic matter inputs, microbial activity, and zinc chemistry in alkaline arid soils. Compost provides a stable carbon source that stimulates microbial proliferation and enzymatic activity, thereby accelerating organic matter decomposition and nutrient mineralization (Gao et al., 2024; Meng et al., 2025). The concurrent increase in microbial biomass carbon (MBC) and microbial biomass nitrogen (MBN) observed in this study reflects enhanced microbial turnover and nutrient immobilization-mineralization dynamics, which are critical indicators of soil functional fertility (Edrisi et al., 2019).

Zinc oxide, when applied alone, is often poorly soluble in calcareous soils due to precipitation and adsorption reactions; however, the presence of zinc-solubilizing bacteria markedly alters this behavior. ZSB are known to release low-molecular-weight organic acids, protons, and chelating compounds that lower rhizosphere pH and convert insoluble Zn compounds into plant-available forms (Sethi et al., 2025). The higher DTPA-extractable Zn and Fe concentrations observed in compost + ZnO + ZSB treatments therefore reflect biologically mediated micronutrient mobilization rather than simple fertilizer addition. Similar synergistic effects of organic amendments and microbial inoculants on micronutrient availability have been reported in other arid and semi-arid systems (Kumar et al., 2025).

Long-term studies have demonstrated that repeated compost and microbial inputs progressively enhance soil organic carbon sequestration, microbial functional diversity, and nutrient buffering capacity, leading to sustained yield improvements over time (Wang et al., 2022, 2025; Shu et al., 2022). Continuous organic inputs promote stable soil aggregates, improved water-holding capacity, and resilient microbial communities, which are particularly critical in arid agroecosystems (Liang et al., 2025). Although the present study was conducted over a single cropping season, the observed improvements in microbial biomass and soil organic matter suggest strong potential for cumulative long-term benefits, as reported in extended compost-based fertilization trials.

Plant growth, measured in terms of plant height and shoot dry biomass, was significantly improved by the Compost + 2 % ZnO + ZSB treatment. These improvements are attributable to enhanced nutrient availability, particularly zinc and nitrogen, resulting from the synergistic effect of the organic matrix, micronutrient enrichment, and microbial solubilization. Zinc plays a critical role in auxin synthesis and enzyme activation (Wang et al., 2023b), and its increased availability in a bioavailable form likely stimulated vegetative growth. Moreover, the compost component improved soil physical structure and provided a steady nutrient supply (Kelbesa, 2021), while ZSB enhanced micronutrient solubility through the production of organic acids and siderophores (Asghar et al., 2024).

The sole application of ZnSO4 or ZnO resulted in comparatively modest gains, indicating the limitations of mineral zinc sources in calcareous or alkaline soils where Zn availability is inherently low due to fixation (Gupta et al., 2024). In contrast, microbial inoculation with ZSB in conjunction with ZnO improved plant growth, suggesting the pivotal role of ZSB in solubilizing ZnO particles (Sethi et al., 2025). Compost + ZSB treatment also performed well, reaffirming the benefits of incorporating biological inputs into organic nutrient management systems.

In terms of yield, the Compost + 2 % ZnO + ZSB treatment consistently showed the highest grain yield. Enhanced grain filling and development can be attributed to the continuous availability of zinc, phosphorus, and nitrogen, facilitated by microbial mineralization and compost-mediated nutrient retention (Campana et al., 2025). Furthermore, the observed increase in 1000-grain weight in treatments involving ZSB aligns with previous research, which reported that ZSB not only solubilizes native zinc but also stimulates root growth and enhances nutrient uptake efficiency (Singh et al., 2024).

Nutrient accumulation in grains, particularly of nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), iron (Fe), and zinc (Zn), was significantly higher in the Compost + 2 % ZnO + ZSB treatment. The improvement in nutrient uptake is primarily linked to enhanced microbial activity, which mobilizes native and added micronutrients and the organic matter that prevents nutrient leaching and enhances cation exchange capacity (Dhaliwal et al., 2024). These results are crucial in the context of human nutrition, particularly in zinc-deficient regions, and support the promotion of agronomic biofortification strategies.

The superior wheat growth and yield response observed under compost + ZnO + ZSB treatment can be mechanistically linked to improved soil biological functioning and micronutrient availability. Zinc plays a pivotal role in enzyme activation, protein synthesis, and auxin metabolism, directly influencing tillering, biomass accumulation, and grain development (Gupta et al., 2025; Sohail et al., 2025). The sustained availability of Zn through microbial solubilization, rather than transient availability from soluble ZnSO4, explains the superior performance of integrated treatments over mineral fertilization alone.

Additionally, compost-mediated improvements in soil structure and water-holding capacity likely alleviated abiotic stress typical of arid soils, indirectly supporting plant growth and nutrient uptake (Rehman et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023a). The observed enhancement in 1000-grain weight and grain yield under ZSB-based treatments aligns with earlier studies demonstrating that microbial inoculants improve root architecture, nutrient acquisition efficiency, and assimilate partitioning during grain filling (Galindo-Castañeda et al., 2022).

The findings of the study validate the hypothesis that integrating organic matter (compost), micronutrient supplementation (ZnO), and microbial inoculants (ZSB) offers a sustainable, efficient, and environmentally friendly strategy to improve crop growth, yield, nutrient density, and soil health. This integrated approach is promising in zinc-deficient soils and can serve as a cornerstone of sustainable agricultural and biofortification efforts in developing regions. Future studies should explore the scalability of the strategy under different agroecological zones and cropping systems, as well as its long-term impacts on soil microbial ecology and plant health.

The economic analysis of wheat cultivation under different zinc fertilization treatments demonstrated that although input costs were higher for treated plots, especially for microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost, the overall profitability was enhanced, particularly under bio-organic fertilization. This aligns with research, which reported that the addition of external nutrient sources in wheat production generally increases variable costs, especially when micronutrient fortification is involved (Ali and Tsou, 1997). Despite the increased costs, the economic benefits in terms of gross margins and net returns were significantly higher for the microbial-assisted zinc-compost treatment. This improvement may be attributed to enhanced nutrient use efficiency and improved plant growth parameters due to the synergistic effects of compost and beneficial microbes. It is evident from the literature that microbial inoculants can promote nutrient solubilization and uptake, translating into higher yields (Sammauria et al., 2020) and better financial returns. The higher net income in the microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost treatment relative to the control suggests that bio-organic-assisted biofortification not only improves soil health and crop yield but also enhances farm-level economic resilience. This strategy offers a sustainable solution for nutrient-deficient soils, supporting the transition towards low-input, high-efficiency farming systems (Akbar et al., 2020).

Although initial input costs were higher with microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost, the significant gains in yield and net return justify its adoption. The data strongly support integrating microbial-assisted composts into conventional fertilization regimes to improve agronomic performance and economic returns under resource-constrained conditions. The present study was conducted under specific soil and climatic conditions and over limited cropping seasons, which may restrict the generalization of results across diverse agroecological zones. Long-term effects on soil microbial diversity, nutrient cycling, and micronutrient buildup were not assessed, and the findings were restricted to wheat without testing in other cropping systems. Future research should therefore focus on multi-location and multi-season trials, long-term soil health monitoring, and extending the approach to different crops. Additionally, developing cost-effective microbial inoculant formulations and delivery mechanisms will be crucial to enhance adoption, particularly by resource-constrained farmers.

The integrated application of microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost (Compost + 2 % ZnO + ZSB) enhances wheat growth, yield, grain nutrient biofortification, and soil fertility compared to sole amendments. This combined treatment consistently outperformed others across both trials, markedly increasing plant height, biomass, grain weight, and yield, while significantly elevating macronutrient (N, P, K) and micronutrient (Fe, Zn) concentrations in grains. Soil chemical and biological parameters also showed pronounced improvements, with enhanced organic matter, microbial biomass, and nutrient availability, underscoring the synergistic effects of organic, microbial, and zinc amendments. These findings highlight the efficacy of integrated nutrient management strategies involving microbial-assisted zinc-enriched compost for sustainable wheat production and soil health restoration, offering promising avenues for addressing micronutrient deficiencies in cereal crops.

The authors confirm that the data, figures, and tables included in this manuscript are original and have not been previously published. The primary data are accessible and can be provided upon request. Relevant data is submitted on the NCBI website, and accession numbers MN696212, MN696213, MN696214, MN696215 and MN696216 are included in the text.

All authors contributed to research and manuscript preparation. Conceptualization: AH, ZI. Methodology: AH, MA, AS. Investigation: AH, AS, MA. Data Curation: AH, MA, EA. Formal Analysis: AH, ZI, AS. Writing – Original Draft: AH, ZI. Writing – Review & Editing: AS, EA, MA. Supervision: MA. Funding Acquisition: EA, MA. All authors reviewed and commented on the previous version of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript for publication.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

The authors express their appreciation to Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2026R317), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, the Department of Soil Science, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Pakistan, and the National Research Program for Universities (NRPU) project number 6292/Punjab/NRPU/R&D/HEC/2016 for providing research facilities.

This work was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting project number (PNURSP2026R317), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

This paper was edited by Maria Jesus Gutierrez Gines and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Akbar, F., Rahman, A. U., and Rehman, A.: Genetic Engineering of Rice to Survive in Nutrient-Deficient Soil, Rice Research for Quality Improvement: Genomics and Genetic Engineering: Volume 1: Breeding Techniques and Abiotic Stress Tolerance, Springer, Singapore, 437–464, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-4120-9_19, 2020.

Ali, M. and Tsou, S. C.: Combating micronutrient deficiencies through vegetables – a neglected food frontier in Asia, Food Policy, 22, 17–38, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-9192(96)00029-2, 1997.

Antreich, S.: Heavy metal stress in plants-a closer look, Protocol of the project practicum “Heavy metal stress in plants”, University of Vienna, 13 pp., https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:55057154, 2012.

Asghar, M. U., Hussain, A., Anwar, H., Dar, A., Ahmad, H. T., Nazir, Q., Tariq, N., and Jamshaid, M. U.: Investigating the Efficacy of Dry Region Zinc Solubilizing Bacteria for Growth Promotion of Maize and Wheat under Axenic Conditions, Plant Health, 3, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.33687/planthealth.03.01.5158, 2024.

Brookes, P. C., Landman, A., Pruden, G., and Jenkinson, D.: Chloroform fumigation and the release of soil nitrogen: a rapid direct extraction method to measure microbial biomass nitrogen in soil, Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 17, 837–842, https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-0717(85)90144-0, 1985.

Campana, E., Ciriello, M., Lentini, M., Rouphael, Y., and De Pascale, S.: Sustainable Agriculture Through Compost Tea: Production, Application, and Impact on Horticultural Crops, Horticulturae, 11, 433, https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11040433, 2025.

Chen, Y., Zhao, X., Zhang, J., Wang, H., Ye, Z., Ma, W., Mao, R., Zhang, S., Dahlgren, R. A., and Gao, H.: Combined application of nitrate and schwertmannite promotes As (III) immobilization and greenhouse gas emission reduction in flooded paddy fields, Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 13, 119845, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2025.119845, 2025.

Clagnan, E., Cucina, M., De Nisi, P., Dell'Orto, M., D'Imporzano, G., Kron-Morelli, R., Llenas-Argelaguet, L., and Adani, F.: Effects of the application of microbiologically activated bio-based fertilizers derived from manures on tomato plants and their rhizospheric communities, Scientific Reports, 13, 22478, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50166-5, 2023.

Dhaliwal, S. S., Sharma, V., and Shukla, A. K.: Impact of micronutrients in mitigation of abiotic stresses in soils and plants – A progressive step toward crop security and nutritional quality, Advances in Agronomy, 173, 1–78, https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.agron.2022.02.001, 2022.

Dhaliwal, S. S., Dubey, S. K., Kumar, D., Toor, A. S., Walia, S. S., Randhawa, M. K., Kaur, G., Brar, S. K., Khambalkar, P. A., and Shivey, Y. S.: Enhanced Organic Carbon Triggers Transformations of Macronutrients, Micronutrients, and Secondary Plant Nutrients and Their Dynamics in the Soil under Different Cropping Systems-A Review, Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition, 24, 5272–5292, https://doi.org/10.1007/s42729-024-01907-6, 2024.

Dincă, L. C., Grenni, P., Onet, C., and Onet, A.: Fertilization and soil microbial community: a review, Applied Sciences, 12, 1198, https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031198, 2022.

Duan, F., Peng, P., Yang, K., Shu, Y., and Wang, J.: Straw return of maize and soybean enhances soil biological nitrogen fixation by altering the N-cycling microbial community, Applied Soil Ecology, 192, 105094, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2023.105094, 2023.

Edrisi, S. A., Tripathi, V., and Abhilash, P. C.: Performance analysis and soil quality indexing for Dalbergia sissoo Roxb. grown in marginal and degraded land of eastern Uttar Pradesh, India, Land, 8, 63, https://doi.org/10.3390/land8040063, 2019.

Estefan, G., Sommer, R., and Ryan, J.: Methods of Soil, Plant, and Water Analysis: A manual for the West Asia and North Africa Region, 3rd edn., Beirut, Lebanon: International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), 65–119, https://www.scribd.com/document/832438758/Soil-Plant-and-Water-Analysis-ICARDA-2013 (last access: 12 February 2026), 2013.

Feliziani, G., Bordoni, L., and Gabbianelli, R.: Regenerative Organic Agriculture and Human Health: The Interconnection Between Soil, Food Quality, and Nutrition, Antioxidants, 14, 530, https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox14050530, 2025.

Feng, W., Zhang, J., Yanqiong, Z., Honghui, W., Xiyu, Z., Yilin, C., Huanhuan, D., Liyun, G., Dahlgren, R. A., and Hui, G.: Arsenic mobilization and nitrous oxide emission modulation by different nitrogen management strategies in a flooded ammonia-enriched paddy soil, Pedosphere, 34, 1051–1065, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedsph.2023.09.008, 2024.

Galindo-Castañeda, T., Lynch, J. P., Six, J., and Hartmann, M.: Improving soil resource uptake by plants through capitalizing on synergies between root architecture and anatomy and root-associated microorganisms, Frontiers in Plant Science, 13, 827369, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.827369, 2022.

Gao, X., Zhang, J., Liu, G., Kong, Y., Li, Y., Li, G., Luo, Y., Wang, G., and Yuan, J.: Enhancing the transformation of carbon and nitrogen organics to humus in composting: Biotic and abiotic synergy mediated by mineral material, Bioresource Technology, 393, 130126, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2023.130126, 2024.

Gupta, G., Virkhare, U., Nimbulkar, P., Jogaiah, S., Khare, E., Dutta, A., and Kher, D.: Role of Zinc-solubilizing bacteria as biostimulants for plant growth promotion and sustainable agriculture, Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology, 141, 102996, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmpp.2025.102996, 2025.

Gupta, N., Gupta, A., Sharma, V., Kaur, T., Rajan, R., Mishra, D., Singh, J., and Pandey, K.: Biofortification of Legumes: Enhancing Protein and Micronutrient Content, in: Harnessing Crop Biofortification for Sustainable Agriculture, Springer, 225–253, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-3438-2_12, 2024.

Hossain, A., Skalicky, M., Brestic, M., Maitra, S., Ashraful Alam, M., Syed, M. A., Hossain, J., Sarkar, S., Saha, S., and Bhadra, P.: Consequences and mitigation strategies of abiotic stresses in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under the changing climate, Agronomy, 11, 241, https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11020241, 2021.

Huang, H., Chen, J., Liu, S., and Pu, S.: Impact of ZnO nanoparticles on soil lead bioavailability and microbial properties, Science of The Total Environment, 806, 150299, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150299, 2022.

Imran: Integration of organic, inorganic and bio fertilizer, improve maize-wheat system productivity and soil nutrients, Journal of Plant Nutrition, 47, 2494–2510, https://doi.org/10.1080/01904167.2024.2354190, 2024.

Jalal, A., Júnior, E. F., and Teixeira Filho, M. C. M.: Interaction of zinc mineral nutrition and plant growth-promoting bacteria in tropical agricultural systems: a review, Plants, 13, 571, https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13050571, 2024.

Jha, P., Biswas, A., Lakaria, B. L., Saha, R., Singh, M., and Rao, A. S.: Predicting total organic carbon content of soils from Walkley and Black analysis, Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis, 45, 713–725, https://doi.org/10.1080/00103624.2013.874023, 2014.

Kachurina, O., Zhang, H., Raun, W., and Krenzer, E.: Simultaneous determination of soil aluminum, ammonium-and nitrate-nitrogen using 1 M potassium chloride extraction, Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis, 31, 893–903, https://doi.org/10.1080/00103620009370485, 2000.

Kelbesa, W. A.: Effect of compost in improving soil properties and its consequent effect on crop production – A review, Journal of Natural Sciences Research, 12, 15–25, https://doi.org/10.7176/JNSR/12-10-02, 2021.

Khan, I., Jan, A. U., Khan, I., Ali, K., Jan, D., Ali, S., Khan, and M. N.: Wheat and berseem cultivation: A comparison of profitability in district Peshawar, Sarhad Journal of Agriculture, 28, 83–88, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A292939605/AONE?u=googlescholar&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=5c270c85, (last access: 12 February 2026), 2012.

Khan, M. T., Aleinikovienė, J., and Butkevičienė, L.-M.: Innovative organic fertilizers and cover crops: Perspectives for sustainable agriculture in the Era of climate change and organic agriculture, Agronomy, 14, 2871, https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14122871, 2024.

Kumar, N. V., Patil, M., Nadagouda, B., and Beerge, R.: Synergistic Effects of Different Composts and Microbial Inoculants on Crop Yield, Soil Fertility, and Microbial Populations, Compost Science & Utilization, 33, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1080/1065657X.2025.2567534, 2025.

Lal, R.: Soil Degradation Effects on Human Malnutrition and Under-Nutrition, Medical Research Archives, 12, https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v12i10.5753, 2024.

Liang, X., Yu, S., Ju, Y., Wang, Y., and Yin, D.: Integrated management practices foster soil health, productivity, and agroecosystem resilience, Agronomy, 15, 1816, https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15081816, 2025.

Lu, S., Zhu, G., Qiu, D., Li, R., Jiao, Y., Meng, G., Lin, X., Wang, Q., Zhang, W., and Chen, L.: Optimizing irrigation in arid irrigated farmlands based on soil water movement processes: Knowledge from water isotope data, Geoderma, 460, 117440, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2025.117440, 2025.

Maitra, S., Shankar, T., Hossain, A., Sairam, M., Sagar, L., Sahoo, U., Gaikwad, D. J., Pramanick, B., Mandal, T. K., and Sarkar, S.: Climate-smart millets production in future for food and nutritional security, in: Adapting to climate change in agriculture-theories and practices, edited by: Sheraz Mahdi, S., Singh, R., and Dhekale, B., Springer, Cham, 11–41, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-28142-6_2, 2024.

Manea, E. E. and Bumbac, C.: Sludge Composting – Is This a Viable Solution for Wastewater Sludge Management?, Water, 16, https://doi.org/10.3390/w16162241, 2024.

Meng, G., Zhu, G., Jiao, Y., Qiu, D., Wang, Y., Lu, S., Li, R., Liu, J., Chen, L., Wang, Q., Huang, E., and Li, W.: Soil salinity patterns reveal changes in the water cycle of inland river basins in arid zones, Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 29, 5049–5063, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-29-5049-2025, 2025.

Mujumdar, S. S., Tikekar, S., and Tapkir, S.: Role of Bacteria in Plant Nutrient Mobilization: A Review, Open Access Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 9, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.23880/oajmb-16000303, 2024.

Naeem, M., Iqbal, Z., Hussain, A., Jamil, M., Ahmad, H. T., Ismail, A. M., El-Mogy, M. M., El Ganainy, S. M., El-Beltagi, H. S., and Hadid, M. L.: Conversion of organic waste into bio-activated zinc-enriched compost to improve the health of deficient soils and wheat yield, Global Nest Journal, 27, 07425, https://doi.org/10.30955/gnj.07425, 2025.

Naseem, S., Hussain, A., Iqbal, Z., Mustafa, A., Mumtaz, M. Z., Manzoor, A., Jamil, M., and Ahmad, M.: Exopolysaccharide and Siderophore Production Ability of Zn Solubilizing Bacterial Strains Improve Growth, Physiology and Antioxidant Status of Maize and Wheat, Polish Journal of Environmental Studies, 31, 1–14, https://doi.org/10.15244/pjoes/140563, 2022.

Olsen, S. R.: Estimation of available phosphorus in soils by extraction with sodium bicarbonate, US Department of Agriculture, https://www.scienceopen.com/document?vid=d646b24b-2996-4ffe-84bb-311a5ce64188 (last access: 16 February 2026), 1954.

Prasath, D., Kandiannan, K., Leela, N., Aarthi, S., Sasikumar, B., and Babu, K. N.: Turmeric: Botany and production practices, Horticultural Reviews, 46, 99–184, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119521082.ch3, 2018.

Qian, S., Zhou, X., Fu, Y., Song, B., Yan, H., Chen, Z., Sun, Q., Ye, H., Qin, L., and Lai, C.: Biochar-compost as a new option for soil improvement: Application in various problem soils, Science of the Total Environment, 870, 162024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162024, 2023.

Rehman, S. U., De Castro, F., Aprile, A., Benedetti, M., and Fanizzi, F. P.: Vermicompost: Enhancing plant growth and combating abiotic and biotic stress, Agronomy, 13, 1134, https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13041134, 2023.

Reimer, M., Kopp, C., Hartmann, T., Zimmermann, H., Ruser, R., Schulz, R., Müller, T., and Möller, K.: Assessing long term effects of compost fertilization on soil fertility and nitrogen mineralization rate, Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science, 186, 217–233, https://doi.org/10.1002/jpln.202200270, 2023.

Ryan, J., Estefan, G., and Rashid, A.: Soil and Plant Analysis Laboratory Manual, 2nd edn., International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), Beirut, Lebanon, https://repo.mel.cgiar.org/items/149b8091-6d46-4a67-9c1e-733c899b5428 (last access: 12 February 2026), 2001.

Sammauria, R., Kumawat, S., Kumawat, P., Singh, J., and Jatwa, T. K.: Microbial inoculants: potential tool for sustainability of agricultural production systems, Archives of Microbiology, 202, 677–693, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00203-019-01795-w, 2020.

Sethi, G., Behera, K. K., Sayyed, R., Adarsh, V., Sipra, B., Singh, L., Alamro, A. A., and Behera, M.: Enhancing soil health and crop productivity: the role of zinc-solubilizing bacteria in sustainable agriculture, Plant Growth Regulation, 105, 601–617, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10725-025-01294-7, 2025.

Sharma, A., Soni, R., and Soni, S. K.: From waste to wealth: exploring modern composting innovations and compost valorization, Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management, 26, 20–48, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-023-01839-w, 2024.

Shu, X., He, J., Zhou, Z., Xia, L., Hu, Y., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y., Luo, Y., Chu, H., and Liu, W.: Organic amendments enhance soil microbial diversity, microbial functionality and crop yields: A meta-analysis, Science of the Total Environment, 829, 154627, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154627, 2022.

Shuman, L. and Duncan, R.: Soil exchangeable cations and aluminum measured by ammonium chloride, potassium chloride, and ammonium acetate, Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis, 21, 1217–1228, https://doi.org/10.1080/00103629009368300, 1990.

Singh, S., Chhabra, R., Sharma, A., and Bisht, A.: Harnessing the power of zinc-solubilizing bacteria: a catalyst for a sustainable agrosystem, Bacteria, 3, 15–29, https://doi.org/10.3390/bacteria3010002, 2024.

Sohail, H., Noor, I., Hussain, H., Zhang, L., Xu, X., Chen, X., and Yang, X.: Genome editing in horticultural crops: Augmenting trait development and stress resilience, Horticultural Plant Journal, 12, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpj.2025.09.001, 2025.

Sreenivasa, M. N.: Organic farming: for sustainable production and environmental protection, in: Microorganisms in Sustainable Agriculture and Biotechnology, edited by: Satyanarayana, T. and Johri, B., Springer, Dordrecht, 55–76, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2214-9_4, 2011.

Wang, D., Lin, J. Y., Sayre, J. M., Schmidt, R., Fonte, S. J., Rodrigues, J. L., and Scow, K. M.: Compost amendment maintains soil structure and carbon storage by increasing available carbon and microbial biomass in agricultural soil – A six-year field study, Geoderma, 427, 116117, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2022.116117, 2022.

Wang, J., Yang, X., Huang, S., Wu, L., Cai, Z., and Xu, M.: Long-term combined application of organic and inorganic fertilizers increases crop yield sustainability by improving soil fertility in maize–wheat cropping systems, Journal of Integrative Agriculture, 24, 290–305, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jia.2024.07.003, 2025.

Wang, Y. X., Yu, T. F., Wang, C. X., Wei, J. T., Zhang, S. X., Liu, Y. W., Chen, J., Zhou, Y. B., Chen, M., Ma, Y. Z., Lan, J. H., Zheng, J. C., Li, F., and Xu, Z. S.: Heat shock protein TaHSP17.4, a TaHOP interactor in wheat, improves plant stress tolerance, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 246, 125694, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.125694, 2023a.

Wang, Z., Wang, Y., Du, Q., Yan, P., Yu, B., Li, W.-X., and Zou, C.-Q.: The auxin signaling pathway contributes to phosphorus-mediated zinc homeostasis in maize, BMC Plant Biology, 23, 1–20, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-023-04039-8, 2023b.

Wang, Z., Fu, X., and Kuramae, E. E.: Insight into farming native microbiome by bioinoculant in soil-plant system, Microbiological Research, 285, 127776, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2024.127776, 2024.

Waterlot, C., Ghinet, A., Dufrénoy, P., Hechelski, M., Daïch, A., Betrancourt, D., and Bulteel, D.: Sustainable pathways to oxicams via heterogeneous biosourced catalysts-Recyclable and reusable materials, Journal of Cleaner Production, 437, 140684, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.140684, 2024.

Younas, N., Fatima, I., Ahmad, I. A., and Ayyaz, M. K.: Alleviation of zinc deficiency in plants and humans through an effective technique; biofortification: A detailed review, Acta Ecologica Sinica, 43, 419–425, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chnaes.2022.07.008, 2023.

Zhao, H., Li, J., Li, X., Hu, Q., Guo, X., Wang, Y., Zhao, Y., and Gan, G. Y.: Response of Soil Organic Carbon and Bacterial Community to Amendments in Saline-Alkali Soils of the Yellow River Delta, European Journal of Soil Science, 76, e70147, https://doi.org/10.1111/ejss.70147, 2025.

Zhu, X.-X., Shi, L.-N., Shi, H.-M., and Ye, J.-R.: Characterization of the Priestia megaterium ZS-3 siderophore and studies on its growth-promoting effects, BMC Microbiology, 25, 133, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-024-03669-8, 2025.