the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Soil fungal network complexity and functional roles differ between black truffle plantations and forests

Vasiliki Barou

Jorge Prieto-Rubio

Mario Zabal-Aguirre

Javier Parladé

Ana Rincón

Black truffle (Tuber melanosporum Vittad.), a valued edible fungus, has been thoroughly studied for its ability to modify soil conditions and influence microbial communities in its environment as it dominates the space. While direct associations of black truffle with microbial guilds offer insights into its competitiveness, the role of these interactions in ecosystem functions remain unclear. This study aims to assess the patterns of soil fungal community within the black truffle brûlés across different producing systems (managed plantations vs wild forests) and seasons (autumn vs spring), to determine the role of T. melanosporum in the structure of the fungal networks, and to identify the contribution of main fungal guilds to soil functioning in these systems. To address this, network analysis was employed to construct the fungal co-occurrence networks in the brûlés of black truffle plantations and wild production areas in forests. Black truffle plantations showed greater fungal homogeneity, network complexity and links compared to forests, indicating enhanced stability, possibly due to reduced plant diversity and uniform conditions, while seasonality did not affect the fungal network structure. Despite its abundancein the brûlés, T. melanosporum was not a hub species in neither truffle-producing systems and exhibited few interactions, mainly with saprotrophs and plant pathogens. Saprotrophic fungi, with partial contributions from ectomycorrhizal and plant pathogen guilds, were the key contributors to carbon and nutrient cycling in both systems. These results improve our understanding of the ecology, biodiversity and functioning of black truffle-dominated soils that could enable more effective management strategies in black truffle plantations.

- Article

(2764 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1471 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Black truffle (Tuber melanosporum Vittad.) is a valued edible fungus naturally produced in Mediterranean ecosystems, where it forms ectomycorrhizal associations with host plants like Quercus spp. Due to its high market value, this fungus has been cultivated beyond its natural distribution area (Reyna and Garcia-Barreda, 2014), and its production has promoted the use of abandoned agricultural lands and contributed in maintaining the soil quality (Leonardi et al., 2021). Either grown in forests or plantations, the black truffle mycelium spreads throughout the area surrounding the colonised trees, reducing the vegetation and giving the appearance of a burnt area called “brûlé” (Streiblová et al., 2012; Schneider-Maunoury et al., 2018).

The colonisation and production success of black truffle has been extendedly studied in relation to the abiotic environment and its effects on the fungus' growth (García-Montero et al., 2007; Garcia-Barreda et al., 2019; Barou et al., 2024). In the light of the niche construction theory, where black truffle is thought to have the ability to modify the surrounding abiotic edaphic conditions (Bragato, 2014; García-Montero et al., 2024), soil biotic components can also be affected by black truffle in a shared niche (Mello et al., 2015). Under the same soil environment, in a process of colonising the space, the black truffle may show antagonistic and/or synergistic interactions with the surrounding microbial communities. For instance, a competitive interaction has been found between T. melanosporum and other ectomycorrhizal fungi (ECM) for host plant and niche colonisation in brûlés (Belfiori et al., 2012; De Miguel et al., 2014), as well as with other truffle species (Marjanović et al., 2020). Further potential competitive effects have been also observed with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) (Barou et al., 2023), molds, yeasts and plant pathogens, whose abundances have been negatively associated with that of T. melanosporum over time (Oliach et al., 2022).

Although the direct associations of black truffle with other microbial guilds have provided some valuable insights regarding its competitiveness, there is still a gap of knowledge on what their role is in the ecosystem functions. Previous work indicated that soil microbial shifts might have functional consequences, affecting important ecosystem processes (Pérez Izquierdo et al., 2017). For example, the competition between ECM and saprotrophic fungi in forest soils for water and nutrients has been considered to suppress decomposition rates, leading to greater carbon sequestration (Bödeker et al., 2016; Fernandez and Kennedy, 2016). However, this phenomenon is not consistent across the world's biomes, as it depends on several environmental and anthropogenic factors (Fernandez and Kennedy, 2016; Choreño-Parra and Treseder, 2024). In this sense, the projected increased temperatures, and decreased precipitations due to global warming (Guiot and Cramer, 2016) are expected to negatively impact the performance of vegetation and associated microorganisms, especially in highly water limited ecosystems, such as the Mediterranean ones (Querejeta et al., 2021). In this context, since ECM fungi are the main receivers of photosynthetic carbohydrates from the host (Itoo and Reshi, 2013), their reduction could accelerate the carbon cycling stimulating saprotrophic activity (Fernández and Kennedy, 2016). It is, therefore, important to study the associations between the soil fungal diversity and functionality considering the particular climate and soil conditions of a given ecosystem.

As it concerns the black truffle producing systems, seasonality can also influence the competitiveness of black truffle and soil microbial shifts, since the dynamics of the fungus change throughout its long life-cycle (Garcia-Barreda et al., 2020), and soil microbiota fluctuates across the seasons as a consequence of temperature, soil moisture and nutrient variation (Koranda et al., 2013; Luo et al., 2019), ultimately impacting soil functionality (Vořiškova et al., 2014; Siles and Margesin, 2017; Júnior et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2024a).

Considering all the above, the research on diversity and dynamics of soil microbial communities, together with the underlying ecological factors, is essential to better understand their functions (Orgiazzi et al., 2012) and to finally ameliorate black truffle production (Antony-Babu et al., 2013). In this sense, the use of network analysis in soil ecology research has increased substantially over the past decade (Guseva et al., 2022). This approach considers taxa that co-occur simultaneously at the same place as being connected by links, ultimately forming networks (Goberna and Verdú, 2022). Analysing these networks has been considered to provide valuable insights into microbial distribution across multiple sites (Wagg et al., 2019; Goberna and Verdú, 2022; Prieto-Rubio et al., 2024), and to allow the exploration of ecological community complexity (Guseva et al., 2022). Recently, Barou et al. (2025) have shown that, together with specific soil properties, black truffle abundance and Ascomycetes richness predict soil enzymatic activity in black truffle plantations. Indeed, the biodiversity and composition of biological communities are inherently associated with soil functioning (Wagg et al., 2021; Prieto-Rubio et al., 2024). In black truffle-dominated systems, the OTU co-occurrence network analysis may contribute to deciphering the patterns of fungal community composition, understanding their complexity, thus allowing a deeper understanding of soil functioning (Barberán et al., 2012; Guseva et al., 2022).

Given the potential habitat effect associated with different land uses on soil microbial community structure (Byers et al., 2024; Piñuela et al., 2024) and functioning (Flores-Rentería et al., 2018; Barou et al., 2025), the study of co-occurring taxa in managed vs wild truffle-producing environments may unravel the intricate ecological dynamics of truffle-dominated brûlés. More specifically, the variation of environmental conditions among these black truffle-producing systems may be linked to variations in functional fungal guilds that could play an important role in organic matter decomposition and nutrient mobilisation (Banerjee et al., 2016). This role, however, is often studied individually for specific guilds while ignoring others inhabiting the same environment (Fernandez and Kennedy, 2016). Studying soil carbon and nutrient cycling in relation to the whole fungal biodiversity is crucial for understanding the nutritional feedback of the plant-soil system and for optimising management strategies of truffle-producing plantations.

In a previous work, we have shown that black truffle abundance negatively relates to soil enzymatic activity (Barou et al., 2025). We now aim to go a step further and uncover the organisation of soil fungal communities, in both managed and wild black truffle-producing systems, to understand the role of T. melanosporum in structuring them, and how this translates into soil functioning. In terms of practical implementation, the precise microbial structure, and the contribution of fungal communities to soil functioning in these systems can valuably inform the development of optimal biofertilisation regimes for truffle cultivation.

The specific objectives of this study were (1) to analyse the effect of black truffle-producing ecosystem (managed vs wild), and seasonal effects (spring vs autumn) on soil fungal communities, and to decipher the role of T. melanosporum structuring them; and (2) to identify the main functional fungal guilds operating in soils of managed and wild truffle dominated systems, and their relative contribution to soil carbon and nutrient cycling.

In our first hypothesis, we expected soil fungal communities to be richer and more complex in forests than in plantations, considering that microorganisms and plants have interacted over long evolutionary time in wild ecosystems (Song et al., 2019; Pérez-Lamarque et al., 2022), and that the environmental conditions in wild ecosystems are less predictable than in managed ones. We also anticipated a differential seasonal impact on soil fungal communities between the two truffle-producing systems and, based on the differences observed in their soil parameters (Barou et al., 2024), we expected soil properties to play a significant role in structuring these communities.

Secondly, we hypothesised that T. melanosporum would markedly contribute to the soil fungal network structure acting as a hub species within the community, i.e., highly connected with other fungi, given the strong black truffle effect inside the brûlé (Streiblová et al., 2012; Barou et al., 2025). This is supported by the fact that hub species connecting multiple species in an ecosystem may play a key role in energy flow, meaningfully affecting biodiversity and productivity (Toju et al., 2018).

Finally, in our third hypothesis, we anticipated finding different representative ecological fungal guilds (i.e., fungi with distinct lifestyles) within the fungal networks in each system, given the distinct organic inputs in wild and managed truffle systems (Barou et al., 2024; Barou et al., 2025), and the distinct dominant mycorrhizal plant species in forests and agricultural systems postulating key microbial functional shifts and nutrient turnover (Phillips et al., 2013). Specifically, we expected a greater prevalence of ECM vs saprotrophs in the fungal network of forests compared to that of plantations, each differentially impacting the soil functioning (i.e., carbon and nutrient cycling) in the respective black truffle-producing systems.

2.1 Experimental design, soil sampling and processing

Eighteen sites along the natural distribution of the black truffle in Spain were selected. Per each site, two types of truffle-producing systems were considered: plantations (17 sites) and forests (10 sites) (Fig. S1 in the Supplement). All plantations are effective truffle producing holm oak monocultures, more than 10 years-old, where standard agriculture management practices for truffle culture (mainly irrigation, tilling and pruning) are regularly conducted. In forests, Quercus ilex L. dominates the uppermost canopy layer. The study sites have continental to Mediterranean climate, with seasonal variations in water availability and a mean altitude of 936 ± 251 (SD) m () (for more details see Barou et al., 2024 and Barou et al., 2025).

Four truffle-productive (according to local owners) Q. ilex trees were selected per site, and a total of 116 trees (68 in plantations and 48 in forests) were sampled in autumn 2019 and spring 2020. A metallic probe (4 cm diameter × 20 cm) was used to extract soil samples from the four orientations between the tree trunk and the limit of the brûlé, which were pooled into a unique composite soil sample per tree. A total of 232 soil samples were collected and stored at 4 °C until processing.

Soil samples were analysed in previous works (Barou et al., 2025) to determine their physico-chemical properties (summarised in Table S1 in the Supplement). As a proxy for soil functioning, the potential activities of eight exoenzymes related with the carbon (β-glucosidase, β-cellobiohydrolase, β-xylosidase, β-glucuronidase and laccase), nitrogen (chitinase and leucineaminopeptidase) and phosphorous (alkaline phosphatase) cycling were calculated, as previously detailed in Barou et al. (2025). Briefly, soil samples (1 g) were incubated overnight in specific buffers at 25 °C. Enzymatic activity was then determined using fluorogenic substrates or by a photometric assay (laccase), with a plate reader at specific excitation/emission wavelengths, and the results were normalised to soil and organic matter content (Pérez-Izquierdo et al., 2017; Barou et al., 2025).

2.2 Molecular and bioinformatics analysis

Soil DNA was extracted and metabarcoding sequencing (Illumina MiSeq) performed by targeting the fungal ITS1 region, as described in Barou et al. (2025), resulting in a final dataset of 231 samples, after a sequencing failure in one plantation sample from the spring campaign. Briefly, the DNA was extracted from 0.25 g of sieved soil using the DNeasy PowerSoil Pro kit (Qiagen, Barcelona, Spain), the fungal diversity was assessed through metabarcoding using the primers ITS1F/ITS2 (Gardes and Bruns, 1993), and blank controls were included in both assays to monitor possible contaminations.

Bioinformatics was conducted with the DADA2 pipeline (Callahan et al., 2016; R Core Team, 2022). Briefly, after primer's removal, sequences were filtered and merged, taxonomically assigned, and clustered into OTUs (97 % similarity), according to the v8.2 UNITE database. A final matrix of 8654 fungal OTUs and 7 151 228 reads was obtained, after removing OTUs with less than five reads. Once the taxonomic assignations were obtained, OTUs closely related to a recognised fungal guild (i.e., saprotrophs, ECM, AMF, plant pathogens, parasites, endophytes, epiphytes or lichens) were identified by the FUNGuild and FungalTraits databases (Tedersoo and Smith, 2013; Tedersoo et al., 2014; Nguyen et al., 2015; Põlme et al., 2020).

Before any further analyses, rarefaction was applied to check for suitable sequencing depth across all samples (Fig. S2 in the Supplement), and the whole database was normalised by dividing the number of sequences (i.e., reads) per OTU in a sample by the total number of sequences of that sample.

2.3 Network analysis

To further investigate the structure of soil fungal communities, co-occurrence network analysis was performed following the methodology described by Prieto-Rubio et al. (2024). For this, the OTU's abundance matrix was first rescaled by the respective minimum sequencing depth for each dataset (i.e., whole dataset, and datasets separated by plantation or forest samples). Low frequent OTUs that appeared in < 10 % of the samples in the respective datasets were discarded (Wagg et al., 2019). Then, to generate the fungal co-occurrence networks, the SPIEC-EASI algorithm was applied to each dataset with the spiec.easi function in the “SpiecEasi” R package (Kurtz et al., 2015). This method seeks to detect links (i.e., co-occurrence) between pairs of nodes (i.e., OTUs), at the same time accounts for the nature of the fungal database, where taxa abundances are not really independent (i.e., given that an increase in the relative abundance of one OTU necessarily implies a decrease in others because they are constrained to sum up to a constant of 100 %) and thus, discarding spurious associations between OTUs (Kurtz et al., 2015). In the resulting networks, positive edge weights indicate positive conditional dependence (co-occurrence), negative edge weights indicate negative conditional dependence (co-exclusion), and the absence of an edge indicates conditional independence. This network-based approach enables the identification of coexistence patterns among fungal species within the brûlé, under the assumption that T. melanosporum is present in all samples. The construction of networks was based on the Meinshausen and Bühlmann (2006) neighbourhood selection method. The lambda ratio was set to 0.01 and, to detect the most parsimonious network, 50 values of lambda for every 100 cross-validation permutations were fitted by using the Stability Approach to Regularisation Selection (StARS) (Liu et al., 2010). The inference of the fungal networks and their preparation for visualisation were performed as described in Birt and Dennis (2021). The resulting fungal networks were graphically represented using the Gephi software v0.10 (Bastian et al., 2009), applying both the Fruchterman-Reingold distribution and ForceAtlas2 attractionrepulsion algorithms in the simulations (Fruchterman and Reingold, 1991; Jacomy et al., 2014).

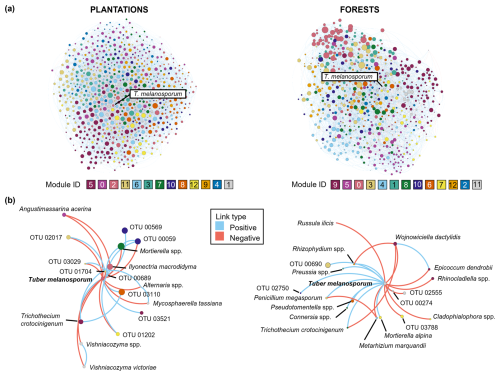

To measure the contribution of each OTU – including that of T. melanosporum – in the network structure, network centrality metrics (degree, eigenvector, closeness, and betweenness centralities; Brede, 2012) and the hub score metric as proxy of keystone taxa (Deguchi et al., 2014), were calculated in Gephi. In addition, the modularity algorithm proposed by Blondel et al. (2008) was also run in Gephi to determine the fungal network divisions into sub-communities, i.e., modules characterised by dense links inside the community compared to the sparser links with other communities (Newman, 2006). The nodes (equivalent to OTUs) belonging to the same module were assigned to a distinctive colour, and the node size was determined by the hub score of that OTU. On the other hand, the links between the nodes were coloured according to the type of association, i.e., positive or negative. To unravel the black truffle interactions with the fungal community, the networks were finally filtered by the links established only with T. melanosporum and positive and negative co-occurrences with other fungi were identified.

2.4 Statistical analysis

In order to assess the effects of the type of truffle production system (hereafter “type”) and different seasons of sampling (hereafter “season”) on soil fungal diversity (hypothesis 1), a linear mixed model (LMM) was first run, with OTU richness (α-diversity) as response variable, type and season as fixed factors (including their interaction), and the site as random factor. The LMM was performed with lmer function from “lme4” R package (Bates et al., 2015) and pairwise comparisons to find significant differences between the different groups were conducted with lsmeans (Lenth, 2016). β-diversity of soil fungal communities was then calculated based on the Bray–Curtis OTU's dissimilarity matrix, and nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) was used to draw the compositional differences within the respective type and season treatments, with the metaMDS function from “vegan” R package (Oksanen et al., 2022). Statistical significance of factors was determined by permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA, permutations = 9999) with the Adonis function using the same Bray–Curtis OTU's dissimilarity matrix, with site included as a strata variable to account for within-site variation. In addition, the vectors of pH, electric conductivity (EC), organic matter (OM), active carbonate, and N, P, K, Mg and Fe content were also fitted in the NMDS with the envfit function to identify the variables significantly correlated with the soil fungal community.

Figure 1(a) Sequencing yields and (b) main taxonomic groups of soil fungal communities, depending on the factors studied: type of black truffle producing system (plantation, forest) and season of sampling (autumn, spring). In (b) percentages represent the mean relative abundance of each phylum and the proportion of Tuber melanosporum (Tmel) abundance that was present in all samples. NA are not taxonomically identified fungal OTUs. N=231 samples, total fungal OTUs = 8654.

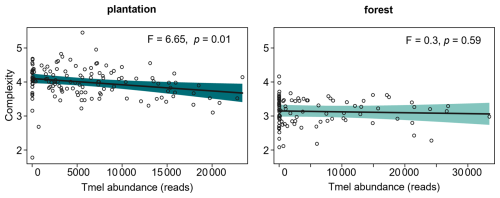

To investigate the impact of the factors type and season on the co-occurrence soil fungal network, we first calculated different structural network properties i.e., OTU richness, the number of links between OTUs and the network complexity (ratio of links to OTU richness) using the total dataset (N=231 samples). The structural network properties were used as response variables in LMMs built with the same fix (type, season) and random (site) factors as described above. Then, co-occurrence networks were separately built for plantations (N=135) and forests (N=96) datasets. To evaluate the contribution of T. melanosporum in the fungal network structure and identify potential hub taxa (hypothesis 2), besides each OTU hubscore, a comparative ranking list among OTUs was calculated (adapted from Brandon-Mong et al., 2020). Briefly, each OTU was first assigned to a rank based on the values of each of its network centrality metrics (degree, eigenvector, closeness, betweenness); then, the rankings of all metrics were summed for each OTU, resulting in a final total rank assigned to each OTU. The top-10 highly ranked OTUs were considered as hub species, and the position of T. melanosporum within this list was used to evaluate its contribution to the soil fungal network structure. In addition, LMMs were built to explore its contribution in the network complexity, using the abundance of T. melanosporum as a fixed factor and the site as random for plantations and forests, separately.

To test the hypothesis 3, the effect of factors type and season on the most representative ecological fungal guilds (i.e., saprotrophs, ECM, AMF, plant pathogens, parasites) and T. melanosporum was first analysed by LMMs, with the relative abundance of each guild as response variable and the model syntaxes similar to that previously explained. Then, to evaluate whether fungal guilds explained soil carbon and nutrient cycling, we performed a model training by the elastic net regularization method (hereafter as ENET model, Zou and Hastie, 2005). This method incorporates least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) and Ridge penalty-based regression modelling, that together allowed to determine how each OTU contributed to predict soil enzymatic activities, by avoiding overfitting and correlation effects between OTUs, and the influence of those that weakly explained variations in enzymatic activities (Zou and Hastie, 2005). For model training, we standardized fungal OTU matrices (plantation/forest) through the decostand function in the “vegan” R package. These matrices were fitted as predictors of soil enzymatic activities (response variables) by 100-fold simulated regressions across 100 alpha-penalty parameters by the optEnet function in the “glmnet” R package. The significant effects of OTUs on each soil enzymatic activity were determined by standardized effect size (SES) from the selected regression model. SES > 1.96 indicated OTUs that positively explained enzymatic activities, while SES < 1.96 did it in OTUs with negative relationships with enzymatic activities. These values allowed us to record all OTUs that predicted soil enzymatic activity and classed by forest/plantation and by functional group (Wagg et al., 2019; Prieto-Rubio et al., 2024).

The graphical representation of results (i.e., α-diversity, abundances of ecological fungal guilds and most abundant fungal taxa) was performed with the “microeco” R package (Liu et al., 2021). All analyses were performed with the R software version 4.2.1 (R Core Team, 2022).

Figure 2Structural properties of soil fungal networks in two types of black truffle producing systems (plantation, forest) and two seasons (autumn, spring): (a) OTU links = number of co-occurrences between OTUs, and (b) network complexity = ratio between the number of links and OTU richness. Bars represent the mean ± SE of each variable (N samples = 231; OTUs = 706, present in > 10 % of samples) and letters indicate significant differences between the treatments of a given factor, derived from linear mixed models and pairwise comparisons (see Table S2).

3.1 Diversity of soil fungal communities

A total of 8654 fungal OTUs were identified, with an average of 325 ± 77 (SD) OTUs per sample. The 38.2 % of all OTUs (N=3309) – that were also the most abundant – were shared in plantations and forests, and close to 30 % of OTUs (low abundant) were uniquely found in each respective truffle producing system (Fig. 1a). Approximately half of the fungal OTUs (the most abundant) were found in both seasons, while 21 %–25 % of them were only found either in autumn or spring, but their relative abundances were just 1 %–2 % of the total (Fig. 1a). Across the soil samples from the two truffle-producing systems and seasons of sampling, the most abundant phylum was Ascomycota, representing 64 %–73 % of the total fungal abundance, followed by Basidiomycota and Mortierellomycota, with 15 %–26 % and 5 %–8 % relative abundance, respectively (Fig. 1b). Tuber melanosporum accounted for 13 %–22 % of the total Ascomycota abundance (all samples yielded T. melanosporum reads), depending on the treatment (Fig. 1b). Among the assigned fungal genera in the total OTU dataset (71 % of OTUs), the top-ten most representative included Tuber, as the most abundant one in both types of truffle-producing systems and both seasons, followed by Mortierella, Solicoccozyma and Fusarium in plantations and Mortierella, Tomentella, Inocybe and Picoa in forests (Fig. S3 in the Supplement).

Contrary to that expected (hypothesis 1), no significant differences in fungal α-diversity were observed between truffle-producing plantations and forests (p=0.142), and only marginal differences due to season were observed (p=0.072) (Fig. S4a in the Supplement). No interaction among factors was detected. However, when β-diversity was analysed, significantly dissimilar fungal communities were found within the treatments of the respective factors studied: type (F = 13.05, p< 0.001, R2 = 0.053) and season (F = 3.8, p< 0.001, R2 = 0.016), and more homogeneous fungal communities were found in plantations than in forests, and in autumn than in spring (Fig. S4b). Fungal β-diversity of plantations was correlated with pH, K and active carbonates, while in forests it was mainly correlated with OM, EC, N, Fe and Mg (Fig. S4b). In terms of seasonal patterns, the fungal community of spring samples likely correlated with more extreme values of pH, OM and Fe, although not always in the same direction (Fig. S4b).

To build the overall co-occurrence fungal network, only frequent fungal OTUs present in at least 10 % of samples were retained, and the total fungal network (N=231 samples) was composed of 706 co-occurring OTUs that showed 4512 links among them. The type of truffle-producing system did significantly affect the structural properties of the network and, contrary to that expected (hypothesis 1), more complex fungal network and more links between taxa were observed in plantations than in forests (Fig. 2, Table S2 in the Supplement). No effect of season was observed on the fungal network properties (Fig. 2, Table S2).

Figure 3Soil fungal networks in the brûlé of black truffle producing plantations (left) and forests (right). For each truffle producing system, the total fungal network with co-occurrences (blue-positive links) and co-exclusions (orange-negative links) between OTUs (a) and the subnetwork composing of Tuber melanosporum with other fungal species (b) are depicted. Each node represents one fungal OTU, among which Tuber melanosporum is highlighted. The node size is related to the hub score index, and the node colour indicates a separate module inferred by Gephi (different colours were assigned to module IDs for each system).

Regarding the node centrality metrics, the top-10 taxa with the highest total ranking in all network metrics (degree, eigenvalue, closeness and betweenness) included nine Ascomycota (Stachybotrys chartarum Corda., Setophaeosphaeria badalingensis Crous and Y. Zhang ter, Arthrinium sp., Chaetosphaeronema sp., Penicillium jensenii K. V. Zaleski, Humicola fuscoatra Traaen, Botryotrichum atrogriseum J. F. H. Beyma, Microdochium novae-zelandiae Hern.-Restr., Thangavel and Crous, and one unclassified Ascomycota OTU), and one Mortierellomycota OTU (Mortierella sp.). Half of these fungi are classed as litter/soil saprotrophs, while the primary lifestyle of the other half is plant pathogens i.e., S. badalingensis, Arthrinium sp., M. novae-zelandiae, Chaetosphaeronema sp. (Põlme et al., 2020). As it concerns the contribution of T. melanosporum in the overall soil fungal network structure, when considering the sum of network properties (degree, eigenvector, closeness, and betweenness), it was in the 163rd position (out of 706), i.e., within the first 23 % of OTUs in network metrics' ranking, and dropped to 37 % (261st position) when only the OTU's hub score (proxy of keystone taxa) was considered. These results seemed to indicate that, contrary to that expected (hypothesis 2), T. melanosporum was not likely acting as a hub species structuring the total co-occurring fungal network inside the brûlé.

Figure 4Relations (mean predicted values) between Tuber melanosporum (Tmel) abundance and the soil fungal network complexity in black truffle producing plantations (N=135) and forests (N=96). The relationships were estimated by linear mixed models, with the site as a random factor. Tmel abundance measured as sequencing reads; no sample had zero Tmel values but low counts, with minimum 4 reads; network complexity was calculated as the ratio of fungal links by the OTU richness. The shaded area represents the 95 % confidence intervals.

3.2 Tuber melanosporum representativeness

To investigate more closely the representativeness of T. melanosporum in each type of truffle-producing system, separate network analyses were further conducted for plantations and forests. The resulting fungal networks were composed of 728 and 641 co-occurring OTUs in plantations and forests, respectively, which were distributed across 13 different modules in both cases (Fig. 3). Each module was composed of at least 25 OTUs and some modules were more central than others (i.e., modules with higher centrality metrics are more relevant and connected within the network), both in plantations (e.g., modules 3 and 6; PERMANOVA, p=0.003, R2 = 0.02) and in forests (e.g., modules 0, 3 and 8; PERMANOVA, p=0.001, R2 = 0.02) (Fig. 3). In addition, in both systems, the OTU' co-occurrences (e.g., positive links) outranked the co-exclusions (e.g., negative links), with plantations showing 10 258 positive vs 2270 negative links (ratio 4.5:1) and forests showing 7918 positive vs 1054 negative links (ratio 7.5:1). As regards T. melanosporum centrality, its position in the network metrics' ranking was 276th in plantations and 58th in forests, i.e., within the first 38 % and 9 % network influential OTUs, respectively, while this position shifted to 35.8 % and 21.2 %, respectively when only the hub score was taken into account. Given that, although in neither truffle-producing system it could be characterised as a hub species, it can be suggested that T. melanosporum likely had a more central role in forests than in plantations.

Tuber melanosporum was connected either positively (co-occurrence) or negatively (co-exclusion) with 2.3 % and 2.8 % of the total fungal OTUs in plantations and forests, respectively (Fig. 3; Table S3 in the Supplement). One third of these connections in plantations and more than half in forests represented co-occurrences of T. melanosporum with other fungi, while the rest of links represented co-exclusions (Table S3), with the ratio of the number of positive/negative links being approximately 0.4 and 1.25 in plantations and forests, respectively. Among these links, Trichothecium crotocinigenum (Schol-Schwarz) Summerb. was the only fungal OTU co-occurring with T. melanosporum in both producing systems (Table S3). Different Mortierella OTUs showed links with T. melanosporum in the co-occurring networks, both in plantations (negative link), and in forests (positive link). Particularly in plantations, T. melanosporum showed negative links with saprotrophic OTUs, both positive and negative links with OTUs characterised as plant pathogens, a negative link with a parasite and a positive link with one AMF OTU (Table S3). On the other hand, in forests, T. melanosporum was linked either positively or negatively with 300 saprotrophic, pathogens, parasites and ECM OTUs (Table S3).

The role of black truffle structuring the soil fungal network was further examined by regression analysis, which revealed that fungal network complexity was reduced as T. melanosporum abundance increased, but only in plantations and not in forests (Fig. 4).

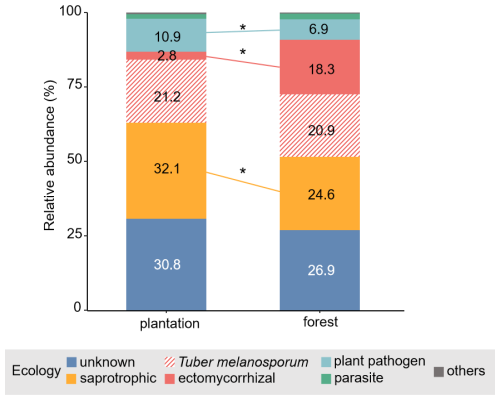

Figure 5Relative abundance of the main ecological fungal guilds, together with Tuber melanosporum, found in each truffle producing system. For a given fungal guild, asterisk represents significant differences between plantations and forests, derived from linear mixed models, with the site as a random factor. “Others” includes fungi classed as arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, endophytes, epiphytes and lichens.

3.3 Ecological fungal guilds and soil functioning

Approximately 54 % of fungal taxa in the networks of both plantations (N=395 out of 728 OTUs in total) and forests (N=346 out of 641 OTUs in total) were assigned to an ecological fungal guild, representing 69 % and 73 % of the total fungal abundance in the respective datasets. In plantations, the relative abundance of saprotrophic (F = 25.9, p< 0.001), but also of plant pathogens (F = 45.1, p< 0.001), was significantly higher than in forests (Fig. 5). As expected (hypothesis 3), a greater abundance of ectomycorrhizal OTUs (other than T. melanosporum) was found in forests than in plantations (F = 88.7, p< 0.001).

Figure 6Contributions of ecological fungal guilds to soil extracellular enzymatic activity in truffle-producing systems (plantations and forests). Heatmaps show the summed estimated values (positive in red and negative in blue) of fungal OTUs for each fungal guild, explaining at least one soil enzymatic activity by ENET models. SAP = saprotrophs, ECM = ectomycorrhizal fungi, PATH = plant pathogens, PAR = parasites. The estimated values are 0.8-scaled.

To test if soil ecological fungal guilds could explain soil carbon and nutrient cycling, the ENET model was performed with the most representative guilds, separately for each type of truffle producing system (Fig. 6). In plantations, saprotrophs did explain both positively (C-related β-glucosidase, β-cellobiohydrolase, β-xylosidase, laccase, and N-related leucineaminopeptidase) and negatively (P-related alkaline phosphatase, and N-related chitinase) the soil enzymatic activities (Fig. 6). By contrast, ECM fungi had a scarce effect explaining soil enzymatic activities. However, plant pathogens did have an overall negative contribution to many of the soil enzymatic activities measured. On the other hand, in forests, saprotrophs had a significant positive effect explaining most of the soil enzymatic activities, particularly cellobiohydrolase related to hemicellulose degradation (Fig. 6). ECM fungi did also explain positively most of the soil enzymatic activities (Fig. 6).

4.1 Diversity of soil fungal communities in wild and managed truffle producing ecosystems

In this study, we assessed the fungal community composition of black truffle brûlés in two types of truffle-producing systems (plantations and forests) and two sampling seasons (spring and autumn). Contrary to our first hypothesis, soil fungal richness was similar in plantations and forests, and between seasons. Although it is usually reported that soil fungal richness decreases when land use intensity increases (Bagella et al., 2014; Brinkmann et al., 2019), the opposite pattern or even unclear changes have also been observed in an extensive literature review (Balami et al., 2020). A study in Quercus-dominated habitats found a strong association of fungal richness with tree species richness (Saitta et al., 2018), and this could explain the similarity of fungal richness in our sampled sites, where Q. ilex was the dominant tree species both in plantations and forests. However, in our regional-scale study, soil fungal β-diversity did show significant differences between the type of truffle producing system and the seasons. A recent study of soil microbial diversity across Europe has identified land-use perturbation, climate, soil properties and vegetation cover as the main influencing factors on soil fungal diversity (Labouyrie et al., 2023). Our results agree with the differences in β-diversity of soil fungal community previously observed in Mediterranean and temperate climate sites, sampled across four seasons (Piñuela et al., 2024), showing a more dispersed fungal community in samples from wild sites than in those of plantations, although in that case no seasonal effects were detected, probably due to the limited number of plots included compared to our study.

Despite the spatial and seasonal differences in our studied sites, soil fungal communities were principally composed of Ascomycota, in agreement with previous works (Fu et al., 2016; Herrero de Aza et al., 2022), while some of the most abundant genera, apart from Tuber, were Mortierella, Solicoccozyma, Fusarium and Tomentella, similarly as detected in other studies (De Miguel et al., 2016; Herrero de Aza et al. 2022). According to Egidi et al. (2019), the dominance of Ascomycota in soil fungal communities is explained not only by their dispersal ability, but also their lifestyles and colonisation ability across multiple niches.

4.2 Soil fungal networks in black truffle-dominated systems

In our study, the fungal co-occurrence network across all sampled black truffle brûlés showed a strong dependency on the type of production system rather than the sampling season, which is consistent with the results of Piñuela et al. (2024). Network links and complexity were higher in plantations than in forests, which may indicate a more stable fungal community in the former system (Griffiths and Philippot, 2013). Recently, Byers et al. (2024) detected that the most densely connected networks are found in land uses under intensive agricultural management, or under naturally regenerating vegetation, rather than in native forests. However, contradictory results regarding soil microbial network complexity and land use intensity and disturbance have been observed in other studies. For example, the conversion of a tropical rainforest to rubber plantation increased the fungal network complexity (Lan et al., 2022), while the opposite occurred with the conversion of a deciduous forest to a coniferous plantation (Nakayama et al., 2019). Zhao et al. (2024) also identified soil fertility -followed by climate- as the primary driver influencing the complexity and stability of soil fungal networks in Mongolian pine plantations. However, they cautioned that the interpretation of network outputs should be approached carefully, as additional factors such as local environmental conditions or plant community composition may also influence the results. Different ecological processes can potentially contribute to changes in co-occurrence patterns of communities at the regional scale, including habitat filtering, competition or neutral processes (Horner-Devine et al., 2007; Maaß et al., 2014). Differences in soil fungal network structure among forest and plantations have been, however, regularly explained by the variation in soil properties (Wang et al., 2024b), or different vegetation cover, and subsequently in rhizosphere conditions (Nakayama et al., 2019; Tang et al., 2024) (i.e., habitat filtering). In this sense, it cannot be discarded that differences in vegetation structure between wild/cultivated sites, i.e., age of trees, canopy cover percentages, amount of soil covered by litter and/or grasses, periodic tillage, or other un-controlled factors have a role structuring soil fungal networks in our study systems. Further work is needed to disentangle the specific ecological processes regulating the biotic (and abiotic) interactions in truffle-dominated ecosystems.

Once T. melanosporum is well established within the brûlé, it spreads throughout the soil possibly acting as a strong environmental filter for plants and soil microbial communities (Napoli et al., 2010; Streiblová et al., 2012). It is worth noting that we observed varying levels of T. melanosporum abundance in well-developed brûlés, which raises questions about whether a simple phenotypic assessment of truffle-dominated soil is sufficient to identify positive samples, and whether higher pooling efforts in soil sampling and/or DNA extraction should be done to minimise soil spatial/temporal heterogeneity, or if amplification efficiency of the ITS1 region alone is adequate (Yang et al., 2018b) – issues that warrant further investigations. In a previous study (Barou et al., 2025), we did show that T. melanosporum abundance was negatively correlated with that of other fungi in wild and managed truffle-producing systems, and with the overall fungal richness in plantations. But surprisingly in this study, despite its presence in the brûlé, T. melanosporum did not appear as hub species (i.e., did not potentially organise community-scale processes of microbial and/or plant interactions in soil; Toju et al., 2018), neither in the whole soil fungal network nor in those separated by plantations and forests, probably because it has already reshaped the microbiome throughout its long-term establishment in the brûlé. Instead, rather saprotrophs and plant pathogens had a central role in the soil fungal network. In fact, in both truffle-producing systems studied, only a very small proportion of taxa of the total fungal community interacted with T. melanosporum. However, in plantations, soil fungal network complexity was negatively impacted by the abundance of black truffle, indicating that although it does not play a prominent role as a hub species, it probably exerts other indirect effects on the structure of the network. In addition, the prevalence of co-exclusions compared to co-occurrences of T. melanosporum with other fungi in plantations indicates the competitive effect of the fungus in this productive system, which may consequently affect the whole fungal network. To confirm this, further research employing pairwise experimental designs that include samplings in/out of the black truffle dominated areas, i.e., the brûlés, would be needed.

Among the most abundant genera, only different Mortierella OTUs were related with T. melanosporum in the co-occurring networks, both in plantations (negative link), and in forests (positive link). Broad geographic and host-plant ranges characterize this saprotrophic fungal genus, which often does not play determinant topological roles in local or regional plant–fungus networks (Toju et al., 2018). Mortierella species have been also reported to collaborate with AMF in phosphorus acquisition (Osorio and Habte, 2001; Tamayo-Velez and Osorio, 2017). In addition, the only common OTU linked with T. melanosporum in both type of production systems was Trichothecium crotocinigenum. According to the fungal trait databases, this fungus was assigned as plant pathogen (primary lifestyle) and litter saprotroph (secondary lifestyle), but it has also been described as an endophytic fungus with antipathogenic effects in potato crops (Yang et al., 2018a; Yang et al., 2020). Further research is needed to understand the positive association of T. melanosporum with this fungal species, as well as the interactions with Mortierella species within the brûlé.

4.3 Functional contribution of soil fungal guilds in the brûlé

Concerning forests and managed truffle-producing systems, significant differences in the abundance of most soil fungal guilds were observed. Saprotrophs and plant pathogens were significantly more abundant in plantations than forests, while the opposite happened for ECM fungi other than T. melanosporum. Since in plantations the host trees had been initially inoculated with T. melanosporum in nurseries, this fungus probably had priority advantage over other ECM species to colonise new root-tips of the host trees (Kennedy and Bruns, 2005). Additionally, soil legacies can play a role since plantations are established in previous agricultural lands usually dominated by saprotrophs, and devoid of ECM propagules compared to forests (Phillips et al., 2013). It has also been reported that intensive land use shapes soil microbial communities and increases the abundance of potential plant pathogens (Idbella and Bonanomi, 2023).

When the different fungal guilds were further tested for their contribution in soil functioning, saprotrophs did significantly predict most of the soil enzymatic activities tested in both truffle-producing systems. A recent study in Mediterranean oak stands showed that saprotrophs were the main fungi responsible for high C and N mineralisation (Adamo et al., 2022); this can be probably related to fast decomposition of high-quality litter by saprotrophs, releasing nutrients in the mineral soil that can be mined by other microorganisms, e.g., mycorrhizal fungi (Fernandez and Kennedy, 2016; Lebreton et al., 2021). It cannot be ruled out that other soil saprotrophs as bacteria can be facilitating N cycling in soil (Phillips et al., 2013). In addition, plant pathogens were negatively related to most soil enzymatic activities in plantations, where their abundance was higher than in forests. Contrary to woodlands, grasslands and croplands are related to a rapid turnover of nutrients and organic matter (Phillips et al., 2013), an easier nutrient leaching out, and a higher soil-borne potential fungal plant pathogens abundance (Romero et al., 2024). Thus, these ecosystems have been proposed to be more reliant than forests on soil health (i.e., capacity of soils to continuously support plant productivity and other ecosystem functions such as nutrient cycling; Lehmann et al., 2020) to regulate their productivity. Finally, ECM fungi were significantly associated with soil enzymatic activity, especially in forests. Recently, Prieto-Rubio et al. (2024) showed that the structure of ECM fungal networks predicted soil enzymatic activities in Mediterranean pine-Quercus mixed forests, although taxa acting as keystone within the fungal networks were not major determinants of soil functioning. In this sense, the association of ECM with the enzymatic activity in forests in our study could represent the indirect effect of T. melanosporum on the network structure. In any case, the extent to which the dominant effect of T. melanosporum is synergistically linked to the dynamics of saprotrophs and/or plant pathogens in plantations, as well as ECM in forests, and the potential functional consequences of these interactions, still requires much more investigation.

In this study, we aimed to define the structure of soil fungal communities associated with black truffle producing plantations and forests, and to decipher the functional relationship between fungal guilds and carbon and nutrient cycling in soils dominated by T. melanosporum. To our knowledge, this is the first study exploring the co-occurrence fungal network structure in black truffle brûlés and identifying fungal links with T. melanosporum. The soil fungal communities were more homogeneous (i.e., more similar taxa) and showed a more complex network structure in plantations than in forests, indicating more stable fungal communities, probably related to the uniform environmental conditions and reduced plant community diversity in monoculture plantations. T. melanosporum had a more central role in the fungal network of forests than in plantations, but in neither system was a hub species despite its dominance in the brûlés, while it showed only a few links with other fungi, mainly with saprotrophic and plant pathogens taxa. Among the ecological fungal guilds, mainly saprotrophs and partially ECM and plant pathogens explained the carbon and nutrient cycling in both truffle-producing systems. Further research based on pairwise experimental designs that include samplings in/out of the black truffle dominated areas, i.e., the brûlés, would help us to clarify the biotic and abiotic transformations induced by T. melanosporum in soils. The findings of this study on fungal biodiversity and the functioning of black truffle-colonised soils offer valuable practical insights, providing a robust scientific foundation to enhance decision-making and drive more effective management strategies, such as those related to fertilisation and soil microbiome management, for black truffle plantations.

The data (raw reads) are available in BioProject under the submission number PRJNA1381543 at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1381543 (last access: 16 December 2025).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-12-1-2026-supplement.

VB: Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. JPR: Writing – review and editing, Validation, Software, Methodology. MZA: Writing – review and editing, Validation, Software, Methodology, Data curation. JP: Writing – review and editing, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. AR: Writing – review and editing, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We gratefully acknowledge all the collaborating stakeholders for their help in defining black truffle productive trees and locations. We also thank Beatriz Pallol, Andrea Vázquez and Adoración Romero for their help in the lab work.

This research has been supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and University (MCIU) through the projects TUBERSYSTEMS (grant no. RTI2018-093907-B-C21/22) and TUBERLINKS (grant no. PID2022-136478OB-C31). This research is part of the thesis of the first author, Vasiliki Barou, who was enrolled in the program of Plant Biology and Biotechnology of Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and holded a pre-doctoral fellowship awarded by MCIU (grant no. PRE2019-091338).

The article processing charges for this open-access publication were covered by the CSIC Open Access Publication Support Initiative through its Unit of Information Resources for Research (URICI).

This paper was edited by Emily Solly and reviewed by Milan Borchert, Julia Schroeder, and one anonymous referee.

Adamo, I., Dashevskaya, S., and Alday, J. G.: Fungal perspective of pine and oak colonization in Mediterranean degraded ecosystems, Forests, 13, 88, https://doi.org/10.3390/f13010088, 2022.

Antony-Babu, S., Deveau, A., Van Nostrand, J. D., Zhou, J., Le Tacon, F., Robin, C., Frey-Klett, P., and Uroz, S.: Black truffle-associated bacterial communities during the development and maturation of Tuber melanosporum ascocarps and putative functional roles, Environ. Microbiol., 16, 2831–2847, https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.12294, 2013.

Bagella, S., Filigheddu, R., Caria, M. C., Girlanda, M., and Roggero, P. P.: Contrasting land uses in Mediterranean agro-silvopastoral systems generated patchy diversity patterns of vascular plants and below-ground microorganisms, Comptes Rendus Biologies, 337, 717–724, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crvi.2014.09.005, 2014.

Balami, S., Vašutová, M., Godbold, D., Kotas, P., and Cudlín, P.: Soil fungal communities across land use types, iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry, 13, 548–558, https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor3231-013, 2020.

Banerjee, S., Kirkby, C. A., Schmutter, D., Bissett, A., Kirkegaard, J. A., and Richardson, A. E.: Network analysis reveals functional redundancy and keystone taxa amongst bacterial and fungal communities during organic matter decomposition in an arable soil, Soil Biol. Biochem., 97, 188–198, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2016.03.017, 2016.

Barberán, A., Bates, S. T., Casamayor, E. O., and Fierer, N.: Using network analysis to explore co-occurrence patterns in soil microbial communities, ISME J., 6, 343–351, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2011.119, 2012.

Barou, V., Rincón, A., Calvet, C., Camprubí, A., and Parladé, J.: Aromatic plants and their associated arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi outcompete Tuber melanosporum in compatibility assays with truffle-oaks, Biology, 12, 628, https://doi.org/10.3390/biology12040628, 2023.

Barou, V., Rincón, A., and Parladé, J.: Modelling environmental drivers of Tuber melanosporum extraradical mycelium in productive holm oak plantations and forests, For. Ecol. Manag., 563, 121988, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2024.121988, 2024.

Barou, V., Zabal-Aguirre, M., Parladé, J., and Rincón, A.: Tuber melanosporum Vittad. abundance and specific soil parameters predict soil enzymatic activity in wild and managed truffle producing systems, Appl. Soil Ecol., 206, 105872, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2025.105872, 2025.

Bastian, M., Heymann, S., and Jacomy, M.: Gephi: An open source software for exploring and manipulating networks, Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 3, 361–362, https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v3i1.13937, 2009.

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., and Walker, S.: Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4, J. Stat. Softw., 67, https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01, 2015.

Belfiori, B., Riccioni, C., Tempesta, S., Pasqualetti, M., Paolocci, F., and Rubini, A.: Comparison of ectomycorrhizal communities in natural and cultivated Tuber melanosporum truffle grounds, FEMS Microbiol. Ecol., 81, 547–561, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6941.2012.01379.x, 2012.

Birt, H. W. G. and Dennis, P. G.: Inference and analysis of SPIEC-EASI microbiome networks, Methods Mol. Biol., 2232, 155–171, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-1040-4_14, 2021.

Blondel, V. D., Guillaume, J.-L., Lambiotte, R., and Lefebvre, E.: Fast unfolding of communities in large networks, J. Stat. Mech.: Theory Exp., 2008, P10008, https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/P10008, 2008.

Bödeker, I. T. M., Lindahl, B. D., Olson, Å., and Clemmensen, K. E.: Mycorrhizal and saprotrophic fungal guilds compete for the same organic substrates but affect decomposition differently, Funct. Ecol., 30, 1967–1978, https://doi.org/10.1111/13652435.12677, 2016.

Bragato, G.: Is truffle brûlé a case of perturbational niche construction?, For. Syst., 23, 349–356, https://doi.org/10.5424/fs/2014232-04925, 2014.

Brandon-Mong, G.-J., Shaw, G. T.-W., Chen, W.-H., Chen, C.-C., and Wang, D.: A network approach to investigating the key microbes and stability of gut microbial communities in a mouse neuropathic pain model, BMC Microbiol., 20, 295, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-020-01981-7, 2020.

Brede, M. (Ed): Book review: Networks – An introduction, Mark E. J. Newman, Oxford University Press, ISBN-978-0-19-920665-0, Artif. Life, 18, 241–242, https://doi.org/10.1162/artl_r_00062, 2012.

Brinkmann, N., Schneider, D., Sahner, J., Ballauff, J., Edy, N., Barus, H., Irawan, B., Budi, S. W., Qaim, M., Daniel, R., and Polle, A.: Intensive tropical land use massively shifts soil fungal communities, Sci. Rep., 9, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-39829-4, 2019.

Byers, A. K., Wakelin, S. A., Condron, L., and Black, A.: Land use change disrupts the network complexity and stability of soil microbial carbon cycling genes across an agricultural mosaic landscape, Microb. Ecol., 87, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-024-02487-9, 2024..

Callahan, B. J., McMurdie, P. J., Rosen, M. J., Han, A. W., Johnson, A. J. A., and Holmes, S. P.: DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data, Nat. Methods, 13, 581–583, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3869, 2016.

Choreño-Parra, E. M. and Treseder, K. K.: Mycorrhizal fungi modify decomposition: a meta-analysis, New Phytol., 242, 2763–2774, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.19748, 2024.

De Miguel, A. M., Águeda, B., Sánchez, S., and Parladé, J.: Ectomycorrhizal fungus diversity and community structure with natural and cultivated truffle hosts: Applying lessons learned to future truffle culture, Mycorrhiza, 24, 5–18, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00572-013-0554-3, 2014.

De Miguel, A. M., Águeda, B., Sáez, R., Sánchez, S., and Parladé, J.: Diversity of ectomycorrhizal Thelephoraceae in Tuber melanosporum-cultivated orchards of Northern Spain, Mycorrhiza, 26, 227–236, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00572-015-0665-0, 2016.

Deguchi, T., Takahashi, K., Takayasu, H., and Takayasu, M.: Hubs and authorities in the world trade network using a weighted HITS algorithm, PLOS ONE, 9, e100338, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0100338, 2014.

Egidi, E., Delgado-Baquerizo, M., Plett, J. M., Wang, J., Eldridge, D. J., Bardgett, R. D., Maestre, F. T., and Singh, B. K.: A few Ascomycota taxa dominate soil fungal communities worldwide, Nat. Commun., 10, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10373-z, 2019.

Fernandez, C. W. and Kennedy, P. G.: Revisiting the `Gadgil effect': Do interguild fungal interactions control carbon cycling in forest soils? New Phytol., 209, 1382–1394, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13648, 2016.

Flores-Rentería, D., Rincón, A., Morán-López, T., Hereş, A.-M., Pérez-Izquierdo, L., Valladares, F., and Curiel Yuste, J.: Habitat fragmentation is linked to cascading effects on soil functioning and CO2 emissions in Mediterranean holm-oak forests, PeerJ, 6, e5857, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.5857, 2018.

Fruchterman, T. M. J. and Reingold, E. M.: Graph drawing by force-directed placement, Softw. - Pract. Exper., 21, 1129–1164, https://doi.org/10.1002/spe.4380211102, 1991.

Fu, Y., Li, X., Li, Q., Wu, H., Xiong, C., Geng, Q., Sun, H., and Sun, Q.: Soil microbial communities of three major Chinese truffles in southwest China, Can. J. Microbiol., 62, 970–979, https://doi.org/10.1139/cjm-2016-0139, 2016.

Garcia-Barreda, S., Sánchez, S., Marco, P., and Serrano-Notivoli, R.: Agro-climatic zoning of Spanish forests naturally producing black truffle, Agric. For. Meteorol., 269–270, 231–238, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2019.02.020, 2019.

Garcia-Barreda, S., Camarero, J. J., Vicente-Serrano, S. M., and Serrano-Notivoli, R.: Variability and trends of black truffle production in Spain (1970–2017): Linkages to climate, host growth, and human factors, Agric. For. Meteorol., 287, 107951, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2020.107951, 2020.

García-Montero, L. G., Manjón, J. L., Pascual, C., and García-Abril, A.: Ecological patterns of Tuber melanosporum and different Quercus Mediterranean forests: Quantitative production of truffles, burn sizes and soil studies, For. Ecol. Manag., 242, 288–296, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2007.01.045, 2007.

García-Montero, L. G., Monleón, V. J., Valverde-Asenjo, I., Menta, C., and Kuyper, T. W.: Niche construction by two ectomycorrhizal truffle species (Tuber aestivum and T. melanosporum), Soil Biol. Biochem., 189, 109276, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2023.109276, 2024.

Gardes, M. and Bruns, T. D.: ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes – application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts, Mol. Ecol., 2, 113–118, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.1993.tb00005.x, 1993.

Goberna, M. and Verdú, M.: Cautionary notes on the use of co-occurrence networks in soil ecology, Soil Biol. Biochem., 166, 108534, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2021.108534, 2022.

Griffiths, B. S. and Philippot, L.: Insights into the resistance and resilience of the soil microbial community, FEMS Microbiol. Rev., 37, 112–129, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00343.x, 2013.

Guiot, J. and Cramer, W.: Climate change: the 2015 Paris Agreement thresholds and Mediterranean basin ecosystems, Science, 354, 465–468, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aah5015, 2016.

Guseva, K., Darcy, S., Simon, E., Alteio, L. V., Montesinos-Navarro, A., and Kaiser, C.: From diversity to complexity: Microbial networks in soils, Soil Biol. Biochem., 169, 108604, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2022.108604, 2022.

Herrero de Aza, C., Armenteros, S., McDermott, J., Mauceri, S., Olaizola, J., Hernández-Rodríguez, M., and Mediavilla, O.: Fungal and bacterial communities in Tuber melanosporum plantations from Northern Spain, Forests, 13, 385, https://doi.org/10.3390/f13030385, 2022.

Horner-Devine, M. C., Silver, J. M., Leibold, M. A., Bohannan, B. J. M., Colwell, R. K., Fuhrman, J. A., Green, J. L., Kuske, C. R., Martiny, J. B. H., Muyzer, G., Øvreås, L., Reysenbach, A.-L., and Smith, V. H.: A comparison of taxon cooccurrence patterns for macro- and microorganisms, Ecology, 88, 1345–1353, https://doi.org/10.1890/06-0286, 2007.

Idbella, M. and Bonanomi, G.: Uncovering the dark side of agriculture: How land use intensity shapes soil microbiome and increases potential plant pathogens, Appl. Soil Ecol., 192, 105090, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2023.105090, 2023.

Itoo, Z. A. and Reshi, Z. A.: The multifunctional role of ectomycorrhizal associations in forest ecosystem processes, Bot. Rev., 79, 371–400, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12229-013-9126-7, 2013.

Jacomy, M., Venturini, T., Heymann, S., and Bastian, M.: ForceAtlas2, a continuous graph layout algorithm for handy network visualization designed for the Gephi software, PLOS ONE, 9, e98679, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0098679, 2014.

Júnior, L., Vieira, G., Noronha, M. F., Cabral, L., Delforno, T. P., de Sousa, S. T. P., Júnior, P. I., Melo, I. S., and Oliveira, V. M.: Land use and seasonal effects on the soil microbiome of a Brazilian dry forest, Front. Microbiol., 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00648, 2019.

Kennedy, P. G. and Bruns, T. D.: Priority effects determine the outcome of ectomycorrhizal competition between two Rhizopogon species colonizing Pinus muricata seedlings, New Phytol., 166, 631–638, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01355.x, 2005.

Koranda, M., Kaiser, C., Fuchslueger, L., Kitzler, B., Sessitsch, A., Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S., and Richter, A.: Seasonal variation in functional properties of microbial communities in beech forest soil, Soil Biol. Biochem., 60, 95–104, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.01.025, 2013.

Kurtz, Z. D., Müller, C. L., Miraldi, E. R., Littman, D. R., Blaser, M. J., and Bonneau, R. A.: Sparse and compositionally robust inference of microbial ecological networks, PLOS Comput. Biol., 11, e1004226, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004226, 2015.

Labouyrie, M., Ballabio, C., Romero, F., Panagos, P., Jones, A., Schmid, M. W., Mikryukov, V., Dulya, O., Tedersoo, L., Bahram, M., Lugato, E., Van Der Heijden, M. G. A., and Orgiazzi, A.: Patterns in soil microbial diversity across Europe, Nat. Commun., 14, 3311, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-37937-4, 2023.

Lan, G., Yang, C., Wu, Z., Sun, R., Chen, B., and Zhang, X.: Network complexity of rubber plantations is lower than tropical forests for soil bacteria but not for fungi, SOIL, 8, 149–161, https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-8-149-2022, 2022.

Lebreton, A., Zeng, Q., Miyauchi, S., Kohler, A., Dai, Y.-C., and Martin, F. M.: Evolution of the mode of nutrition in symbiotic and saprotrophic fungi in forest ecosystems, Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst., 52, 385–404, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-012021-114902, 2021.

Lehmann, J., Bossio, D. A., Kögel-Knabner, I., and Rillig, M. C.: The concept and future prospects of soil health, Nat. Rev. Earth Environ., 1, 544–553, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-020-0080-8, 2020.

Lenth, R. V.: Least-Squares Means: The R Package lsmeans, J. Stat. Softw., 69, https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v069.i01, 2016.

Leonardi, M., Iotti, M., Pacioni, G., R. Hall, I., and Zambonelli, A.: Truffles: Biodiversity, ecological significances, and biotechnological applications, in: Industrially important fungi for sustainable development, edited by: Abdel-Azeem, A. M., Yadav, A. N., Yadav, N., and Usmani, Z., Fungal Biology, Springer, Cham, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-67561-5_4, 2021.

Liu, C., Cui, Y., Li, X., and Yao, M.: microeco: An R package for data mining in microbial community ecology, FEMS Microbiol. Ecol., 97, fiaa255, https://doi.org/10.1093/femsec/fiaa255, 2021.

Liu, H., Roeder, K., and Wasserman, L.: Stability approach to regularization selection (StARS) for high dimensional graphical models, Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst., 24, 1432–1440, 2010.

Luo, X., Wang, M. K., Hu, G., and Weng, B.: Seasonal change in microbial diversity and its relationship with soil chemical properties in an orchard, PLOS ONE, 14, e0215556, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215556, 2019.

Maaß, S., Migliorini, M., Rillig, M. C., and Caruso, T.: Disturbance, neutral theory, and patterns of beta diversity in soil communities, Ecol. Evol., 4, 4766–4774, https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.1313, 2014.

Marjanović, Ž., Nawaz, A., Stevanović, K., Saljnikov, E., Maček, I., Oehl, F., and Wubet, T.: Root-associated mycobiome differentiate between habitats supporting production of different truffle species in Serbian riparian forests, Microorganisms, 8, 1331, https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8091331, 2020.

Meinshausen, N. and Bühlmann, P.: High-dimensional graphs and variable selection with the Lasso, Ann. Stat., 34, https://doi.org/10.1214/009053606000000281, 2006.

Mello, A., Lumini, E., Napoli, C., Bianciotto, V., and Bonfante, P.: Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal diversity in the Tuber melanosporum brûlé, Fungal Biol., 119, 518–527, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.funbio.2015.02.003, 2015.

Nakayama, M., Imamura, S., Taniguchi, T., and Tateno, R.: Does conversion from natural forest to plantation affect fungal and bacterial biodiversity, community structure, and co-occurrence networks in the organic horizon and mineral soil?, Forest Ecol. Manag., 446, 238–250, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2019.05.042, 2019.

Napoli, C., Mello, A., Borra, A., Vizzini, A., Sourzat, P., and Bonfante, P.: Tuber melanosporum, when dominant, affects fungal dynamics in truffle grounds, New Phytol., 185, 237–247, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03053.x, 2010.

Newman, M. E. J.: Modularity and community structure in networks, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103, 8577–8582, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0601602103, 2006.

Nguyen, N. H., Smith, D., Peay, K., and Kennedy, P.: Parsing ecological signal from noise in next generation amplicon sequencing, New Phytol., 205, 1389–1393, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.12923, 2015.

Oksanen, J., Simpson, G. L., Blanchet, F. G., Kindt, R., Legendre, P., Minchin, P. R., O'Hara, R. B., Solymos, P., Stevens, M. H. H., Szoecs, E., and Wagner, H.: vegan: Community ecology package (R package version 2.6-4), CRAN [code], https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (last access: 5 January 2026), 2022.

Oliach, D., Castaño, C., Fischer, C. R., Barry-Etienne, D., Bonet, J. A., Colinas, C., and Oliva, J.: Soil fungal community and mating type development of Tuber melanosporum in a 20-year chronosequence of black truffle plantations, Soil Biol. Biochem., 165, 108510, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2021.108510, 2022.

Orgiazzi, A., Lumini, E., Nilsson, R. H., Girlanda, M., Vizzini, A., Bonfante, P., and Bianciotto, V.: Unravelling soil fungal communities from different Mediterranean land-use backgrounds, PLoS ONE, 7, e34847, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0034847, 2012.

Osorio, N. W. and Habte, M.: Synergistic influence of an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus and a P solubilizing fungus on growth and P uptake of Leucaena leucocephala in an Oxisol, Arid Land Res. Manag., 15, 263–274, https://doi.org/10.1080/15324980152119810, 2001.

Pérez-Izquierdo, L., Zabal-Aguirre, M., Flores-Rentería, D., González-Martínez, S. C., Buée, M., and Rincón, A.: Functional outcomes of structural shifts in fungal communities driven by tree genotype and spatial-temporal factors in Mediterranean pine forests, Environ. Microbiol., 19, 1639–1645, https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.13690, 2017.

Perez-Lamarque, B., Petrolli, R., Strullu-Derrien, C., Strasberg, D., Morlon, H., Selosse, M.-A. and Martos, F.: Structure and specialization of mycorrhizal networks in phylogenetically diverse tropical communities, Environ. Microbiome, 17, 38, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40793-022-00434-0, 2022.

Phillips, R. P., Brzostek, E., and Midgley, M. G.: The mycorrhizal-associated nutrient economy: A new framework for predicting carbon–nutrient couplings in temperate forests, New Phytol., 199, 41–51, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.12221, 2013.

Piñuela, Y., Alday, J. G., Oliach, D., Castaño, C., Büntgen, U., Egli, S., Martínez Peña, F., Dashevskaya, S., Colinas, C., Peter, M., and Bonet, J. A.: Habitat is more important than climate for structuring soil fungal communities associated in truffle sites, Fungal Biol., 128, 1724–1734, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.funbio.2024.02.006, 2024.

Põlme, S., Abarenkov, K., Henrik Nilsson, R., Lindahl, B. D., Clemmensen, K. E., Kauserud, H., Nguyen, N., Kjøller, R., Bates, S. T., Baldrian, P., Frøslev, T. G., Adojaan, K., Vizzini, A., Suija, A., Pfister, D., Baral, H.- O., Järv, H., Madrid, H., Nordén, J., Liu, J. K., Pawlowska, J., Põldmaa, K., Pärtel, K., Runnel, K., Hansen, K., Larsson, K. H., Hyde, K. D., Sandoval-Denis, M., Smith, M. E., Toome-Heller, M., Wijayawardene, N. N., Menolli, N., Reynolds, N. K., Drenkhan, R., Maharachchikumbura, S. S. N., Gibertoni, T. B., Læssøe, T., Davis, W., Tokarev, Y., Corrales, A., Soares, A. M., Agan, A., Machado, A. R., Argüelles-Moyao, A., Detheridge, A., de Meiras-Ottoni, A., Verbeken, A., Dutta, A. K., Cui, B. K., Pradeep, C. K., Marín, C., Stanton, D., Gohar, D., Wanasinghe, D. N., Otsing, E., Aslani, F., Griffith, G. W., Lumbsch, T. H., Grossart, H. P., Masigol, H., Timling, I., Hiiesalu, I., Oja, J., Kupagme, J. Y., Geml, J., Alvarez-Manjarrez, J., Ilves, K., Loit, K., Adamson, K., Nara, K., Küngas, K., Rojas-Jimenez, K., Bitenieks, K., Irinyi, L., Nagy, L. G., Soonvald, L., Zhou, L. W., Wagner, L., Aime, M. C., Öpik, M., Mujica, M. I., Metsoja, M., Ryberg, M., Vasar, M., Murata, M., Nelsen, M. P., Cleary, M., Samarakoon, M. C., Doilom, M., Bahram, M., Hagh-Doust, N., Dulya, O., Johnston, P., Kohout, P., Chen, Q., Tian, Q., Nandi, R., Amiri, R., Perera, R. H., Chikowski, R. S., Mendes-Alvarenga, R. L., Garibay-Orijel, R., Gielen, R., Phookamsak, R., Jayawardena, R. S., Rahimlou, S., Karunarathna, S. C., Tibpromma, S., Brown, S. P., Sepp, S. K., Mundra, S., Luo, Z. H., Bose, T., Vahter, T., Netherway, T., Yang, T., May, T., Varga, T., Li, W., Coimbra, V. R. M., de Oliveira, V. R. T., de Lima, V. X., Mikryukov, V. S., Lu, Y., Matsuda, Y., Miyamoto, Y., Kõljalg, U., and Tedersoo, L.: FungalTraits: A user-friendly traits database of fungi and fungus-like stramenopiles, Fungal Divers., 105, 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13225-020-00466-2, 2020.

Prieto-Rubio, J., Garrido, J. L., Alcántara, J. M., Azcón-Aguilar, C., Rincón, A., and López-García, Á.: Ectomycorrhizal fungal network complexity determines soil multi-enzymatic activity, SOIL, 10, 425–439, https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-10-425-2024, 2024.

Querejeta, J. I., Schlaeppi, K., López-García, Á., Ondoño, S., Prieto, I., van der Heijden, M. G. A., and del Mar Alguacil, M.: Lower relative abundance of ectomycorrhizal fungi under a warmer and drier climate is linked to enhanced soil organic matter decomposition, New Phytol., 232, 1399–1413, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17661, 2021.

R Core Team.: R: A language and environment for statistical computing, R foundation for statistical computing [Software], https://www.R-project.org (last access: 5 January 2026), 2022.

Reyna, S. and Garcia-Barreda, S.: Black truffle cultivation: A global reality, For. Syst., 23, 317–328, https://doi.org/10.5424/fs/2014232-04771, 2014.

Romero, F., Labouyrie, M., Orgiazzi, A., Ballabio, C., Panagos, P., Jones, A., Tedersoo, L., Bahram, M., Guerra, C. A., Eisenhauer, N., Tao, D., Delgado-Baquerizo, M., García-Palacios, P., and van der Heijden, M.: Soil health is associated with higher primary productivity across Europe, Nat. Ecol. Evol., 8, 1847–1855, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-024-02511-8, 2024.

Saitta, A., Anslan, S., Bahram, M., Brocca, L., and Tedersoo, L.: Tree species identity and diversity drive fungal richness and community composition along an elevational gradient in a Mediterranean ecosystem, Mycorrhiza, 28, 39–47, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00572-017-0806-8, 2018.

Schneider-Maunoury, L., Leclercq, S., Clément, C., Covès, H., Lambourdière, J., Sauve, M., Richard, F., Selosse, M.-A., and Taschen, E.: Is Tuber melanosporum colonizing the roots of herbaceous, non-ectomycorrhizal plants?, Fungal Ecol., 31, 59–68, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.funeco.2017.10.004, 2018.

Siles, J. A. and Margesin, R.: Seasonal soil microbial responses are limited to changes in functionality at two Alpineforest sites differing in altitude and vegetation, Sci. Rep., 7, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-02363-2, 2017.

Song, H., Singh, D., Tomlinson, K. W., Yang, X., Ogwu, M. C., Slik, J. W. F., and Adams, J. M.: Tropical forest conversion to rubber plantation in southwest China results in lower fungal beta diversity and reduced network complexity, FEMS Microbiol. Ecol., 95, fiz092, https://doi.org/10.1093/femsec/fiz092, 2019.

Streiblová, E., Gryndlerová, H., and Gryndler, M.: Truffle brûlé: An efficient fungal life strategy, FEMS Microbiol. Ecol., 80, 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01283.x, 2012.

Tamayo-Velez, A. and Osorio, N. W.: Co-inoculation with an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus and a phosphate-solubilizing fungus promotes the plant growth and phosphate uptake of avocado plantlets in a nursery, Botany, 95, 539–545, https://doi.org/10.1139/cjb-2016-0224, 2017.

Tang, X., Yang, J., Lin, D., Lin, H., Xiao, X., Chen, S., Huang, Y., and Qian, X.: Community assembly of ectomycorrhizal fungal communities in pure and mixed Pinus massoniana forests, J. Environ. Manag., 362, 121312, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.121312, 2024.

Tedersoo, L. and Smith, M. E.: Lineages of ectomycorrhizal fungi revisited: Foraging strategies and novel lineages revealed by sequences from belowground, Fungal Biol. Rev., 27, 83–99, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbr.2013.09.001, 2013.

Tedersoo, L., Bahram, M., Põlme, S., Kõljalg, U., Yorou, N. S., Wijesundera, R., Ruiz, L. V., Vasco-palacios, A. M., Thu, P. Q., Suija, A., Smith, M. E., Sharp, C., Saluveer, E., Saitta, A., Rosas, M., Riit, T., Ratkowsky, D., Pritsch, K., Põldmaa, K., Piepenbring, M., Phosri, C., Peterson, M., Parts, K., Pärtel, K., Otsing, E., Nouhra, E., Njouonkou, A. L., Nilsson, R. H., Morgado, L. N., Mayor, J., May, T. W., Majuakim, L., Lodge, D. J., Lee, S. S., Larsson, K. H., Kohout, P., Hosaka, K., Hiiesalu, I., Henkel, T. W., Harend, H., Guo, L. D., Greslebin, A., Grelet, G., Geml, J., Gates, G., Dunstan, W., Dunk, C., Drenkhan, R., Dearnaley, J., De kesel, A., Dang, T., Chen, X., Buegger, F., Brearley, F. Q., Bonito, G., Anslan, S., Abell, S., and Abarenkov, K.: Global diversity and geography of soil fungi, Science, 346, 1256688, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1256688, 2014.

Toju, H., Tanabe, A. S., and Sato, H.: Network hubs in root-associated fungal metacommunities, Microbiome, 6, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-018-0497-1, 2018.

Vořiškova, J., Brabcová, V., Cajthaml, T., and Baldrian, P.: Seasonal dynamics of fungal communities in a temperate oak forest soil, New Phytol., 201, 269–278, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.12481, 2014.

Wagg, C., Schlaeppi, K., Banerjee, S., Kuramae, E. E., and Van Der Heijden, M. G. A.: Fungal-bacterial diversity and microbiome complexity predict ecosystem functioning, Nat. Commun., 10, 4841, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12798-y, 2019.

Wagg, C., Hautier, Y., Pellkofer, S., Banerjee, S., Schmid, B., and Van Der Heijden, M. G.: Diversity and asynchrony in soil microbial communities stabilizes ecosystem functioning, eLife, 10, e62813, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.62813, 2021.

Wang, M., Masoudi, A., Wang, C., Zhao, L., Yang, J., and Yu, Z.: Seasonal variations affect the ecosystem functioning and microbial assembly processes in plantation forest soils, Front. Microbiol., 15, 1391193, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1391193, 2024a.

Wang, M., Sui, X., Wang, X., Zhang, X., and Zeng, X.: Soil fungal community differences in manual plantation larch forest and natural larch forest in northeast China, Microorganisms, 12, 1322, https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12071322, 2024b.

Yang, H.-X., Ai, H.-L., Feng, T., Wang, W.-X., Wu, B., Zheng, Y.-S., Sun, H., He, J., Li, Z.-H., and Liu, J.-K.: Trichothecrotocins A–C, antiphytopathogenic agents from potato endophytic fungus Trichothecium crotocinigenum, Org. Lett., 20, 8069–8072, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.orglett.8b03735, 2018a.

Yang, H.-X., He, J., Zhang, F.-L., Zhang, X.-D., Li, Z.-H., Feng, T., Ai, H.-L., and Liu, J.-K.: Trichothecrotocins D–L, antifungal agents from a potato-associated Trichothecium crotocinigenum, J. Nat. Prod., 83, 2756–2763, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jnatprod.0c00695, 2020.