the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Preface: Illuminating soil's hidden dimensions, a decade of progress and future directions in agrogeophysics research

Alejandro Romero-Ruiz

Dave O'Leary

Dongxue Zhao

Sarah Garré

One century ago, within the context of crop yield investigations conducted at Rothamsted Research in the UK, William Haines and Bernard Keen measured the spatial variability of soil mechanical resistance attaching a dynamometer to a plough, and argued: “a measurement of the degree of variation of soil characteristics over any area on which variety, or manurial, or implement trials are being made, would be of the greatest value”. This initial idea has since grown, acknowledging the links between agricultural management and soil variability, giving rise to the field of Agrogeophysics. This discipline has evolved to harness geophysical methods for non-invasive, multiscale mapping and monitoring of key soil properties as well as physical, chemical and biological processes occurring in the plant-soil-atmosphere continuum. These range from soil texture, soil structure, and water fluxes to soil organic carbon and nutrient dynamics, all which are highly relevant for climate regulation, as well as food and water security. In this preface, we present an overview of advances to the field of Agrogeophysics in the last decade and discuss how the contributions to the Special Issue “Agrogeophysics: Illuminating soil's hidden dimensions” may help addressing major agricultural and related environmental challenges. We expect agrogeophysical studies to continue growing to help lessen the pressure of our agricultural lands caused by food demands of a growing population and climate change induced decline.

- Article

(2021 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Soil, alongside air and water, is one of the three pillars of environmental quality (Bünemann et al., 2018) and is recognised as a significant, yet poorly understood natural resource of the planet. It hosts ∼ 25 % of the global biodiversity and acts as the growth medium for ∼ 95 % of global food production (EU, 2005; JRC, 2012). As the industry responsible for feeding the planet, agriculture is considered the main “user” of this natural resource, managing the soil to ensure food production meets growing global demand (Van Dijk et al., 2021). To achieve this, it is crucial to develop a comprehensive understanding of the impacts of agricultural land use and management practices in the spatial and temporal variation of soil physical, biological and chemical properties and related soil functioning, the contribution of agricultural practices to climate change mitigation as well as their own resilience to climate change. This poses many challenges to the agricultural sector.

Agricultural practices intensify as a result of the increase in global food demand, often resulting in land use changes, overfertilization, increased water use, soil degradation, and decreased biodiversity. This intensification leads to ground and surface water contamination caused by nitrogen leaching from fertilisers (Wang et al., 2019), elevated greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by degraded soils and drained peat soils (Pulido-Moncada et al., 2022; Swindles et al., 2019), soil organic carbon (SOC) stocks decline (Sanderman et al., 2017) and a decline in crop yields by soil degradation (Obour and Ugarte, 2021). The economic implications are substantial both through decline in productivity and in the form of public health costs related to environmental degradation (Farber et al., 2002; Graves et al., 2015; Pretty et al., 2000; Preza-Fontes et al., 2023). These challenges highlight the urgent need for sustainable management practices achieving productivity with environmental stewardship, helping to mitigate the adverse impacts of modern agriculture on ecosystems and human health.

A significant challenge in achieving agricultural sustainability lies in the accurate characterization and monitoring of soil properties and processes (Giuffré et al., 2021), including their state, seasonal and spatial variability, and their responses to different management practices and environmental stressors. While traditional soil sampling methods provide reliable and detailed data, they are limited in their ability to capture extensive areas or monitoring temporal changes efficiently. Geophysical techniques offer a valuable addition to soil sampling, as they can detect subsurface physical, chemical and biological properties across larger areas in a minimally invasive way. Advances in computing power, machine learning, and autonomous survey technologies (e.g., uncrewed aerial vehicles; UAV's) have further enhanced the ability to implement geophysical surveys and to process complex datasets, increasing the accessibility, robustness and efficiency of these methods for agricultural applications. As a result, geophysics has found its place in agricultural studies profiting on its capabilities for the multi-scale delineation of soil properties and states (e.g., soil texture, soil structure, soil water content, SOC) using tomographic and mapping approaches, as well as monitoring water and nutrient partitions resulting from soil-plant-atmosphere interactions. These developments have contributed to the emergence and growth of Agrogeophysics (Becker et al., 2025; Garré et al., 2021) that harnesses geophysical methods to support sustainable agricultural practices.

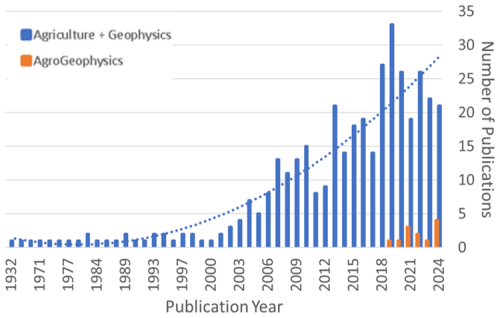

The beginning of the field of Agrogeophysics may be attributed to the seminal work of Haines and Keen (1925) that investigated the variability of soil mechanical resistance in Rothamsted Research using a dynamometer attached to a plough. Yet, the first time “Agriculture” and “Geophysics” were used combined (on Titles, Abstract and Keywords) is from a surveyors manual published in 1935 (Darwin, 1935). Since then, there have been 386 publications (Fig. 1) that combined agriculture and geophysics with a notable rise occurring since the early 2000's, which also coincides with a general increase in publications in environmental sciences. The increased attention in agrogeophysical research has been strongly promoted by increases in computer power driving the rise in the use of geophysics across multiple disciplines and growing the recognition of the value of geophysical techniques to assist addressing challenges posed by agriculture. An extensive analysis by Becker et al., (2025) on peer-reviewed publications and patents concerning Agrogeophysics, confirms the growth of the field and its adaptability, with applications ranging from mapping and monitoring of soil physical, biological and chemical properties, plant phenotyping, yield prediction, and precision agriculture. As agriculture continues to diversify and face new pressures, this adaptability of geophysical methods offers the potential for innovative solutions across all farming systems, contributing to the global efforts for developing sustainable agricultural practices.

Figure 1Number of Scopus search results for “Agriculture” AND “Geophysics” (Blue) vs. search for “Agrogeophysics” (Orange) organised by year of publication.

The Special Issue “Agrogeophysics: Illuminating soil hidden dimensions” bundles research works representative of the most recent advances in this field, highlighting advances and gaps in the research which may act as stepping points for future research. In this preface article, we first provide a glance of the developments on agrogeophysical research achieved in the previous decade. This short review sets the ground to discuss how the articles in this special issue contribute to the field of Agrogeophysics and may help in addressing some of the most prominent challenges in agriculture.

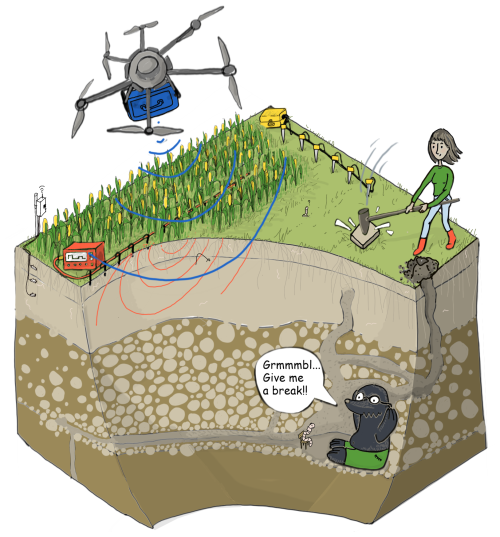

Geophysical methods are currently the only means for non-destructive and large-scale characterization of soils, bridging spatial gaps of small-scale soil sensors and broad scale airborne or satellite data. Because of this, they are increasingly used in the context of agricultural research (Fig. 2). This section provides a non-exhaustive overview of the some of the most exciting recent developments of geophysical methods and innovations proposed in the last decade and since the last special issue on Agrogeophysics (Garré et al., 2021).

Figure 2Illustration of acquisition of geophysical data with commonly used methods ERT, GPR, seismic, soil sensors. The soil is presented as a complex environment hosting cropland and grassland, as well as micro, meso and macrofauna. Geophysical methods are currently the only means for non-destructive and large-scale characterization of soils (Illustration by Sarah Garré, inspired by HYDRAS illustration Miel Vandepitte).

2.1 Advances in established Agrogeophysical methods

Geoelectrical and electromagnetic methods such as direct current resistivity (DC-resistivity), ground penetrating radar (GPR), and electromagnetic induction (EMI) have been at the forefront of agrogeophysics. They are well-established, with robust data processing tools, and are relatively easy to adapt for multiple spatial and temporal scales. These methods sense geophysical properties (i.e., electrical resistivity and dielectric constant) that are strongly dependent on soil properties of interest for agricultural research (Romero-Ruiz et al., 2018). In addition, pedophysical relations abound linking the soil electrical resistivity and dielectric constant to soil properties and states of interest (such as soil texture, soil moisture, salinity, and porosity). Although dealing with uncertainty in pedophysical relationships remains challenging, the usage of these methods will continue to be central in agrogeophysics.

Recent developments of geoelectrical methods have focused on the profile scale to characterize soil-plant-interactions by monitoring soil electrical properties at a high temporal resolution. This has enabled to capture distinctive soil water dynamics patterns that can be associated to agricultural management impacting soil habitats (e.g., tillage and compaction; Blanchy et al., 2020a; Romero-Ruiz et al., 2022), water inputs by irrigation management (Chou et al., 2024), and climate stresses such as drought (Mary et al., 2023). The versatility of the EMI method for rapidly covering large areas has instead facilitated its integration with other data types for delineating soil properties and states of interest at the field scale. For example, EMI data has been integrated with plant information from drone-borne near infrared survey to delineate soil compaction (von Hebel et al., 2021), and with gamma ray spectrometry data to map SOC content variations at the field scale (Rentschler et al., 2020).

Likewise, the GPR, targeting the soil dielectric properties, has seen significant developments in the last decade (Klotzsche et al., 2018). Because the dielectric constant of soil is very sensitive to soil moisture, GPR provides a powerful tool to monitor and map soil moisture variations in agricultural fields. Field-scale shallow soil moisture mapping has received considerable attention in GPR research. Examples of this include the developing of processing algorithms to overcome high attenuation of data in clayey soils (Algeo et al., 2016), and the development of systems and data processing schemes for drone-borne GPR data acquisition and soil moisture estimation (Wu et al., 2019). In addition, due to the differences in water retention properties associated with different soil textures, GPR is also a useful tool to detect and map soil layering, and delineate within-soil sharp interfaces. Recent GPR applications capitalizing on this include the delineation of interfaces resulting from compaction (Wang et al., 2016), the detection of “lost” drainage pipe systems in agricultural lands (Koganti et al., 2021), and the delineation of peatland extension and depths (Henrion et al., 2024).

2.2 Emerging methods in Agrogeophysics

Seismic methods are underused, yet very relevant for agrogeophysics. They offer unique capabilities to probe the mechanical state of the soil at scales for which information is otherwise unavailable. This is very important to assess the soil mechanical resistance (modified by compaction or soil structure breakage) that ultimately determines the suitability of soil systems to host crops, and the synergies between roots, micro and mesofauna for improved soil health. Hence, efforts dealing with seismic research have focused on understanding the footprint of experimental compaction using tomographic approaches. This allows to investigate 2D spatial variability of soil mechanical resistance at the plot scale (Carrera et al., 2024). In addition, seismic properties are very sensitive to the soil water moisture through the so-called suction stress resulting from capillary forces at the pore scale (Romero-Ruiz et al., 2021; Solazzi et al., 2021). An ongoing area of research is dedicated of profiting on this to uses seismic methods for monitoring soil moisture dynamics (Pasquet et al., 2016). This concept has already been successfully employed in recent developments of Distributed Acoustic Sensing (DAS) surveying to monitor soil moisture variations related to slope stability (Kang et al., 2025). Seismic methods will remain a relevant method in agrogeophysics, and

the ideas mentioned above will continue developing for applications in agricultural research, despite potential difficulties of interpreting variations of seismic properties linked to both water content/potential variations and soil (structure) mechanical status resulting from soil consolidation, tillage or compaction.

Spectral induced polarization is growing in its applications in agrogeophysics because of its unique ability of capturing soil biochemical processes that other methods are not sensitive to (Kessouri et al., 2019; Revil et al., 2017). While data collection and data interpretation remain challenging, recent progress has been made on capturing SOC stocks using tomographic configurations that is linked with hotspots of microbial activity (Katona et al., 2021), and for estimation of root distribution across the soil profile (Michels et al., 2025; Tsukanov and Schwartz, 2021).

Gamma ray (radiometrics) has proven effective for soil texture mapping, as gamma emissions correlate with parent material and clay content, enabling differentiation of soil types and subsoil constraints when combined with EMI and machine learning approaches (Jones et al., 2020; Rouze et al., 2017). For soil moisture mapping, gamma rays are affected by the presence of moisture in the pore space of soils (Zreda et al., 2012). By acquiring data over time, either as in-situ measurements or via multiple survey campaigns, radiometrics may have the ability give insight into soil moisture changes over time (Andreasen et al., 2025). This is an area of ongoing research. Additionally, gamma radiometrics complements electromagnetic data by improving discrimination between moisture and textural effects, supporting precision irrigation and amelioration strategies (Franz et al., 2020). Gamma radiometric surveys have been applied to estimate SOC indirectly, as mineralogical variations influence SOC distribution, making radiometrics a valuable input for predictive SOC models in digital soil mapping frameworks (Jones et al., 2020). Airborne gamma ray surveys have also shown ability to predict the presence of peat soils at multiple scales (regional to field), with modern sensors now being adapted for drone surveys, increasing the use of this method at field scales (O'Leary et al., 2025b).

Cosmic Ray Neutron Sensing (CRNS) has emerged as a robust method for soil moisture mapping at field to landscape scales, bridging the gap between point-based sensors and satellite observations. By detecting epithermal neutrons moderated by hydrogen atoms in soil water, CRNS provides non-invasive, spatially integrated soil moisture estimates over footprints of tens of hectares and depths of 10–30 cm (Zreda et al., 2012). Recent studies demonstrate its integration into hydrological models, where CRNS data improved soil moisture and evapotranspiration simulations, highlighting its potential for irrigation scheduling and drought monitoring (Franz et al., 2020). Compared to traditional methods, CRNS reduces sampling bias from soil heterogeneity and offers continuous monitoring, making it a key tool for precision agriculture and water resource management (Franz et al., 2020).

2.3 Methodological developments: data combination, machine learning and modelling

Recent progress is not only situated in the measurement methods or application areas, but also in the methodological aspects of data processing and interpretation. Developments on data fusion typically comprise the cooperative processing of different geophysical methods to advantage complementary sensitivities of physical properties (Henrion et al., 2024), multi-scale combination of geophysical methods with other techniques to advance upscaling for mapping applications (Cimpoiasu et al., 2021; Comas et al., 2017; Khatkar et al., 2025), and profiting on complementary sensitivity to plant/crop properties by drone-borne or remotely sensed multispectral data to characterize crop systems (Falco et al., 2021; von Hebel et al., 2021).

The increased capabilities for multi-data acquisition and the resulting increased volume of data collected demands the development of data processing approaches that allow the interpretation of the measured data sets. This has led to novel data processing algorithms for a new acquisition set-up, such as the data processing tools for drone-born GPR data (Wu and Lambot, 2022), and SIP tomography (Moser et al., 2023). Unsupervised machine learning algorithms can be used to classify dense multi-dimensional spatial data, such as those acquired during agrogeophysical surveys, into zones with similar geophysical response. These techniques were initially adapted from satellite remote sensing (Brogi et al., 2019) and later incorporated advanced neural network classification methods which resulted in increased predictability between EMI and soil physical properties (O'Leary et al., 2024).

Open-source software for geophysical data processing is a key aspect that has contributed to the development of Agrogeophysics. Most available software packages provide tools dealing with modelling the “established agrogeophysical methods” such as DC-resistivity (Blanchy et al., 2020c; Ingeman-Nielsen and Baumgartner, 2006), EMI (Elwaseif et al., 2017; Hanssens et al., 2019; McLachlan et al., 2021) and GPR (Plattner, 2020). In addition to such single-method packages, multi-method packages enable processing different types of geophysical data together (coupled or joint modelling and inversion) (Cockett et al., 2015; Rücker et al., 2017). Interpreting geophysical data remains a central challenge in agrogeophysics. In this context, coupling geophysical modelling frameworks with modelled soil (hydrological) processes can greatly contribute to realising the full potential of geophysical data. This is often done by introducing conceptual models of the soil-plant system and exploring how these models impact both soil functions in agroecosystems and their corresponding geophysical signatures. Such type of frameworks have been successfully used to estimate soil hydraulic and crop properties to guide the quantitative assessment of water fluxes (Blanchy et al., 2020b; Chou et al., 2024; Kuhl et al., 2018), linking field-scale variations of soil physical properties with larger scale satellite-based crop information (Brogi et al., 2020), and can be useful to constrain soil information in agroecological studies dealing for example with pests proliferation and soil-animal interactions (Hbirkou et al., 2011; Romero-Ruiz et al., 2024).

In this section, we highlight how the contributions to this Special Issue integrate into the field of Agrogeophyisics. The articles are contextualized by how each may help addressing the most prominent challenges for sustainable agriculture. These articles will help to pave the way to more integrated and systematic application of geophysical methods in agricultural studies.

3.1 Water fluxes in agroecosystems

Water management is one of the major challenges in sustainable agriculture. The retention and fluxes of water across the soil profile determine plant available water, environment for microbial communities, trace gas production and flux, and groundwater recharge. These all have prominent roles in soil services such as food production, climate regulation and water purification (Vereecken et al., 2022). Quantifying and monitoring soil water dynamics is crucial to better understand or manage these processes and geophysical methods are particularly well-established in this context, where large-scale mapping of soil moisture is highly relevant. In the manuscript entitled “High-resolution near-surface electromagnetic mapping for the hydrological modeling of an orange orchard”, Peruzzo et al. (2025) present a promising approach to capture soil moisture variations in agroforestry systems for calibrating hydrogeophysical models. While mapping soil moisture dynamics with diverse geophysical methods is a promising field of research, special care needs to be considered including accuracy, and accounting for undesired effects of additional variables such as temperature, salinity, texture, etc. In the work “Pooled error variance and covariance estimation of sparse in situ soil moisture sensor measurements in agricultural fields in Flanders”, Hendrickx et al. (2025) compared soil moisture data from soil samples and point sensors from agricultural fields across Flanders, Belgium to demonstrate how point-scale sensor measurements contain systematic spatiotemporal related errors that are also management zone specific. Using a hydrological inverse modelling example, the authors highlight how accounting for these errors is relevant to reduce uncertainty in parameter estimation. This is highly relevant for soil moisture estimation as agrogeophysical methods rely on the calibration of physically-based or empiric pedophysical relationships between soil moisture and soil electrical resistivity or dielectric constant.

Disentangling the effects of different soil traits on the electrical measurements made by geophysical methods remains a challenge when obtaining accurate estimates of soil moisture. In many agricultural contexts, it is crucial to identify and separate the signal coming from both water content and water conductivity variations. In the manuscript “An in-situ methodology to separate the contribution of soil water content and salinity to EMI-based soil electrical conductivity”, Autovino et al. (2025) provided a methodology to disentangle effects of salinity and soil water content in EMI signal using a semi-empirical pedophysical model that explicitly accounts for both parameters. It is expected that future studies will account for these errors to improve prediction of water dynamics in soil systems using ERT, EMI and GPR methods.

While there is a clear tendency to advance large-scale quantification of soil moisture, accounting for different sources of errors, using methods such as EMI, GPR, cosmic ray, and gamma ray, it is also expected that plot scale studies for detailed monitoring of soil moisture dynamics are needed. These studies offer robust approach to assess water partitions that are associated with interactions between climatic regimes, soil texture, water use efficiency by plants and soil structure. This is particularly relevant in the context of climate change where climate extremes such as droughts and flooding are expected. Blanchy et al. (2025) highlight the value of geophysical methods for extreme climate research in their manuscript “Closing the phenotyping gap with non-invasive belowground field phenotyping”. Therein the authors used ERT to monitor soil moisture variations of distinct plant genotypes under experimentally induced drought regimes. The resulting ERT transects and temporally monitored changes in electrical conductivity during the growing season provided evidence of crop variety-specific responses to the induced water stresses, indicating that some crops may be more resilient to predicted climate extremes. This controlled geophysical plot-scale monitoring experiment is an important element that informs of below ground water usage by crops in phenotyping experiments and may as well be relevant in biodiversity studies where capturing spatial heterogeneity in water usage is crucial (Weisser et al., 2017). In addition, plot scale studies will remain relevant to explore how geophysical methods can help advancing mechanistic models of agricultural systems by helping the inference of conceptual models used in simulations as well as the parameter estimation.

3.2 Nutrient cycling

Agricultural fertilization is acknowledged to be the major disruptor on the global nutrient cycling. This raises concerns related to the increase on greenhouse gasses emissions from the soil as well as nitrate and phosphate leaching that contaminates groundwater (Stein and Klotz, 2016). A complete understanding of the relative contributions impacting nutrient use efficiency remains elusive as it depends on the soil texture, soil structure, climate, crop and induced fertilization practices. In this sense, geophysical methods that can map textural changes and soil layering across large areas are relevant. Such methods offer indirect information on how applied fertilizers may interact with different zones within an agricultural land. Geophysical methods can also be integrated into nutrient cycling studies by assisting the quantification of soil moisture dynamics and hence infer water retention and transport properties that ultimately determine the movement of nutrients across the soil profiles.

Obtaining direct information about the nutrient dynamics in the soils is more challenging as electrical and dielectric properties sensed by the most established methods are not so sensitive to nutrient concentrations in the soil. In the manuscript “Assessing soil fertilization effects using time-lapse electromagnetic induction”, Kaufmann et al. (2025) explored the possibility of using EMI and ERT to quantify legacy effects of fertilizations practices in an experimental field in Germany. They found that EMI data generally did not carry information about fertilization practices, yet ERT data could successfully identify the impact of fertilization practiced of low and high application rates. Their results are promising and will offer a new avenue of research on how to use electrical methods to help monitoring fertilization practices in agricultural soils. Another promising application of geophysical methods quantifying nutrient use efficiency was proposed by Mendoza Veirana et al. (2025) in their manuscript “Exploring the link between cation exchange capacity and magnetic susceptibility”. In their work, they explored the sensitivity of the soil magnetic susceptibility to cation exchange capacity (CEC) that is typically deemed as a surrogate variable for soil nutrient retention capacities. Their study demonstrated a high correlation between CEC measured in soil samples and field and laboratory measured magnetic susceptibility for various agricultural soils in Belgium.

3.3 Soil (structure) degradation

Another major soil service is to provide habitats for all types of living organisms including grass, crops and micro, meso and macro-fauna. Soil degradation is of particular importance for agricultural applications and can be typically seen as soil structure degradation. Soil structure, the spatial organization of pore spaces and soil solid phase and its mechanical status, is a very important soil trait that slowly develops as a result of biological activity and synergistically provides a better habitat for the organisms that the soil is hosting (Kibblewhite et al., 2008). Despite its relevance for soil functioning, soil structure is very fragile and therefore can be greatly disturbed by the most common agricultural practices such as compaction by harvesting operations, and overgrazing. In this context, recent studies have been prominently dedicated to developing techniques for quantifying soil compaction. Most studies focus on quantifying soil compaction before and after experimental compaction. These studies exploit the ability of electrical geophysical methods to capture compaction induced increases in the connectivity of the electrically conductive solid phase of the soil, and higher soil water saturation. In the manuscript “Uncovering soil compaction: performance of electrical and electromagnetic geophysical methods”, Carrera et al. (2024) present an advancement on this area by comparing ERT and EMI methods to infer soil compaction from the measured electrical resistivity of the soil in an experimental field in Italy. The observed anomalies can be associated with compaction through soil bulk density data independently collected from soil samples. They discussed the need to consider the higher spatial resolution offered by ERT against the practicality and ability to cover large areas of EMI when a study is conceived.

Once again, a major challenge in utilizing geophysical methods to detect and monitor soil structure degradation for remediation and prevention, is the limited ability to disentangle the signal of interest (in this case soil structure) from other soil properties that vary as a function of space and time. Future research should be dedicated to providing robust tools to circumvent this issue through the combination of different geophysical methods for simultaneous interpretation by coupled tomographic and/or machine learning approaches. Finally, mechanistic modelling of soil structure deformation, compaction, tillage, pore structure dynamics is rapidly developing field. Coupling such models with pedophysical, soil process models, and geophysical models is another avenue for future research that puts soil structure dynamics at the center and can provide information on its impact on larger-scale easy to measure geophysical properties.

3.4 Soil carbon cycling

SOC dynamics are highly relevant in the context of climate change as agricultural practices are typically known to negatively impacts soil carbon storage and produce losses due to land use changes and soil degradation. Most of the current sustainable agricultural practices (such as crop rotation, reduced tillage, usage of organic fertilizers, and rotational grazing, etc) are developed to promote soil carbon sequestration to ameliorate the impact of agriculture to climate change (Dupla et al., 2024). Assessing the impact of such management strategies on the SOC stocks as a function of time and space remains very challenging. Geophysical methods are developing to address this spatial gap at multiple scales. At the plot scale, the development of reliable SIP tomography is gaining territory as it has been demonstrated that the complex electrical conductivity is correlated to SOC in both organic and mineral soils (Katona et al., 2021). This experimental evidence remains anecdotic and the chemo-physical mechanisms behind this correlation are not fully understood. However, this research area holds great potential in agrogeophysics and future research may be dedicated to the design of laboratory and field experiments that can provide further insights on the links of SIP signals and SOC content and lead to the development of empirical or physically based relationships between these two that can be systematically used as those used for other methods. In addition, drone borne GPR and radiometrics have been successfully use to map and monitor change in SOC content associated with the thickness and spatial extent of peatland (Henrion et al., 2024).

Geophysical methods may find their application on soil carbon sequestration through restoration and management of organic soils through the assessment of the efficacy of such intervention practices. O'Leary et al. (2025b) discussed this approach in their manuscript “Assessing the impact of rewetting agricultural fen peat soil via open drain damming: an agrogeophysical approach”. In this work they monitored the effectives of a damming technique for rewetting an agricultural peat soil in Ireland using EMI methods. With the help of seasonally monitored EMI data and an unsupervised ML algorithm they identified localized infiltration 20 m away from the dam, highlighting the need for spatial geophysical data to assess the impacts of rewetting efforts.

3.5 Food production

Food security in a world with a growing population, increasing demand for products with large environmental footprints, and changing climate is arguably the most impactful challenge for agricultural research during this century (Luchtenbelt et al., 2024). Sustainable food production intersects the challenges of efficient soil water and nutrient management, soil health maintenance and restoration, and soil carbon sequestration. Precision agriculture has been both addressed from the soil perspective using geophysical methods to monitor soil properties and states and from the plant perspective using ground based, drone borne and remotely sensed data to infer plant traits. The combinations of both perspectives should be however desired as they complement each other and can only together offer accurate insights more “precise” management strategies. Although not very common, such combination has been explored recently in the literature. In their manuscript “Combining electromagnetic induction and remote sensing data for improved determination of management zones for sustainable crop production”, Dogar et al. (2025) explored the possibility of combining EMI data with remotely sensed NDVI data for management zone delineation while discussing the potential gains of data combination as compared with management zones derived from one data source only. Their results demonstrated that crop yields maps are heavily influenced by soil texture as sensed by the EMI data and proposed a methodology to systematically infer management zones by clustering normalized parameters obtained from these two data types using an unsupervised machine learning algorithm.

As we mark ten years of progress in agrogeophysics, the field stands at a pivotal juncture. The integration of geophysical methods into agricultural research has not only illuminated the hidden dimensions of soil-plant-atmosphere systems but also fostered collaboration between disciplines and innovation in data processing and modelling. Looking ahead, the challenge lies in translating these scientific advances into scalable, field-ready solutions that support sustainable agriculture and climate resilience. By continuing to refine methodologies, embrace emerging technologies, and strengthen global partnerships, agrogeophysics can play a transformative role in shaping the future of food systems and environmental stewardship.

Conceptualization: ARR, DOL, SG. Writing original draft: ARR, DOL. Review and editing: all authors.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

ARR acknowledges support from FARMWISE (EU Horizon Europe/Swiss SERI GA no. 101135533), the European Joint Program for SOIL (EJP SOIL, subproject SoilCompaC, GA no. 86269) and the SNSF Scientific Exchanges grant (no. 222642).

This research has been supported by the EU HORIZON EUROPE European Research Council (grant nos. 86269 and 101135533) and the Swiss National Science Fundation Scientific Exchanges grant (grant no. 222642).

Algeo, J., Van Dam, R. L., and Slater, L.: Early-time GPR: a method to monitor spatial variations in soil water content during irrigation in clay soils, Vadose Zone Journal, 15, https://doi.org/10.2136/vzj2016.03.0026, 2016.

Andreasen, M., Van der Veeke, S., Limburg, H., Koomans, R., and Looms, M. C.: Soil Moisture Time Series Using Gamma-Ray Spectrometry Detection Representing a Scale of Tens-of-Meters, Water Resources Research, 61, e2024WR039534, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024WR039534, 2025.

Autovino, D., Coppola, A., De Mascellis, R., Farzamian, M., and Basile, A.: An in-situ methodology to separate the contribution of soil water content and salinity to EMI-based soil electrical conductivity, EGUsphere [preprint], https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2025-2696, 2025.

Becker, S. M., Franz, T. E., Ge, Y., Luck, J. D., and Heeren, D. M.: Geophysical tools for agricultural management: Trends, challenges, and opportunities, Vadose Zone Journal, 24, e70029, https://doi.org/10.1002/vzj2.70029, 2025.

Blanchy, G., Deroo, W., De Swaef, T., Lootens, P., Quataert, P., Roldán-Ruíz, I., Versteeg, R., and Garré, S.: Closing the phenotyping gap with non-invasive belowground field phenotyping, SOIL, 11, 67–84, https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-11-67-2025, 2025.

Blanchy, G., Watts, C. W., Richards, J., Bussell, J., Huntenburg, K., Sparkes, D. L., Stalham, M., Hawkesford, M. J., Whalley, W. R., and Binley, A.: Time-lapse geophysical assessment of agricultural practices on soil moisture dynamics, Vadose Zone Journal, 19, e20080, https://doi.org/10.1002/vzj2.20080, 2020a.

Blanchy, G., Watts, C. W., Ashton, R. W., Webster, C. P., Hawkesford, M. J., Whalley, W. R., and Binley, A.: Accounting for heterogeneity in the θ–σ relationship: Application to wheat phenotyping using EMI, Vadose Zone Journal, 19, e20037, https://doi.org/10.1002/vzj2.20037, 2020b.

Blanchy, G., Saneiyan, S., Boyd, J., McLachlan, P., and Binley, A.: ResIPy, an intuitive open source software for complex geoelectrical inversion/modeling, Computers & Geosciences, 137, 104423, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2020.104423, 2020c.

Brogi, C., Huisman, J. A., Pätzold, S., von Hebel, C., Weihermüller, L., Kaufmann, M. S., van der Kruk, J., and Vereecken, H.: Large-scale soil mapping using multi-configuration EMI and supervised image classification, Geoderma, 335, 133–148, 2019.

Brogi, C., Huisman, J., Herbst, M., Weihermüller, L., Klosterhalfen, A., Montzka, C., Reichenau, T., and Vereecken, H.: Simulation of spatial variability in crop leaf area index and yield using agroecosystem modeling and geophysics-based quantitative soil information, Vadose Zone Journal, 19, e20009, https://doi.org/10.1002/vzj2.20009, 2020.

Bünemann, E. K., Bongiorno, G., Bai, Z., Creamer, R. E., Deyn, G. D., de Goede, R., Fleskens, L., Geissen, V., Kuyper, T. W., Mäder, P., Pulleman, M., Sukkel, W., van Groenigen, J. W., and Brussaard, L.: Soil quality – A critical review, Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 120, 105–125, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.01.030, 2018.

Carrera, A., Peruzzo, L., Longo, M., Cassiani, G., and Morari, F.: Uncovering soil compaction: performance of electrical and electromagnetic geophysical methods, SOIL, 10, 843–857, https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-10-843-2024, 2024.

Carrera, A., Barone, I., Pavoni, M., Boaga, J., Ferro, N. D., Cassiani, G., and Morari, F.: Assessment of different agricultural soil compaction levels using shallow seismic geophysical methods, Geoderma, 447, 116914, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2024.116914, 2024.

Chou, C., Peruzzo, L., Falco, N., Hao, Z., Mary, B., Wang, J., and Wu, Y.: Improving evapotranspiration computation with electrical resistivity tomography in a maize field, Vadose Zone Journal, 23, e20290, https://doi.org/10.1002/vzj2.20290, 2024.

Cimpoiasu, M. O., Kuras, O., Wilkinson, P. B., Pridmore, T., and Mooney, S. J.: Hydrodynamic characterization of soil compaction using integrated electrical resistivity and X-ray computed tomography, Vadose Zone Journal, https://doi.org/10.1002/vzj2.20109, 1–15, 2021.

Cockett, R., Kang, S., Heagy, L. J., Pidlisecky, A., and Oldenburg, D. W.: SimPEG: An open source framework for simulation and gradient based parameter estimation in geophysical applications, Computers & Geosciences, 85, 142–154, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2015.09.015, 2015.

Comas, X., Terry, N., Hribljan, J. A., Lilleskov, E. A., Suarez, E., Chimner, R. A., and Kolka, R. K.: Estimating belowground carbon stocks in peatlands of the Ecuadorian páramo using ground-penetrating radar (GPR), Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, 122, 370–386, 2017.

Darwin, E. R. H.: The Training of Surveyors, Australian Surveyor, 5, 336–344, https://doi.org/10.1080/00050326.1935.10436433, 1935.

Dogar, S. S., Brogi, C., O'Leary, D., Hernández-Ochoa, I. M., Donat, M., Vereecken, H., and Huisman, J. A.: Combining electromagnetic induction and satellite-based NDVI data for improved determination of management zones for sustainable crop production, SOIL, 11, 655–679, https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-11-655-2025, 2025.

Dupla, X., Bonvin, E., Deluz, C., Lugassy, L., Verrecchia, E., Baveye, P. C., Grand, S., and Boivin, P.: Are soil carbon credits empty promises? Shortcomings of current soil carbon quantification methodologies and improvement avenues, Soil Use and Management, 40, e13092, https://doi.org/10.1111/sum.13092, 2024.

Elwaseif, M., Robinson, J., Day-Lewis, F. D., Ntarlagiannis, D., Slater, L. D., Lane, J. W., Minsley, B. J., and Schultz, G.: A matlab-based frequency-domain electromagnetic inversion code (FEMIC) with graphical user interface, Computers & Geosciences, 99, 61–71, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2016.08.016, 2017.

EU: EU Soil Strategy for 2030, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52021DC0699 (last access: 27 July 2023), 2021.

Falco, N., Wainwright, H. M., Dafflon, B., Ulrich, C., Soom, F., Peterson, J. E., Brown, J. B., Schaettle, K. B., Williamson, M., Cothren, J. D., Ham, R. G., McEntire, J. A., and Hubbard, S. S.: Influence of soil heterogeneity on soybean plant development and crop yield evaluated using time-series of UAV and ground-based geophysical imagery, Scientific Reports, 11, 7046, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-86480-z, 2021.

Farber, S. C., Costanza, R., and Wilson, M. A.: Economic and ecological concepts for valuing ecosystem services, Ecological Economics, 41, 375–392, 2002.

Franz, T. E., Wahbi, A., Zhang, J., Vreugdenhil, M., Heng, L., Dercon, G., Strauss, P., Brocca, L., and Wagner, W.: Practical Data Products From Cosmic-Ray Neutron Sensing for Hydrological Applications, Frontiers in Water, 2, https://doi.org/10.3389/frwa.2020.00009, 2020.

Garré, S., Hyndman, D., Mary, B., and Werban, U.: Geophysics conquering new territories: The rise of “agrogeophysics,” Vadose Zone Journal, e20115, https://doi.org/10.1002/vzj2.20115, 2021.

Giuffré, G., Ricci, A., Bisoffi, S., Dönitz, E., Voglhuber-Slavinsky, A., Helming, K., Evgrafova, A., Ratinger, T., and Robinson, D. A.: Mission area: Soil health and food, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, https://doi.org/10.2777/038626, 2021.

Graves, A. R., Morris, J., Deeks, L. K., Rickson, R. J., Kibblewhite, M. G., Harris, J. A., Farewell, T. S., and Truckle, I.: The total costs of soil degradation in England and Wales, Ecological Economics, 119, 399–413, 2015.

Haines, W. B. and Keen, B. A.: Studies in soil cultivation. II. A test of soil uniformity by means of dynamometer and plough, The Journal of Agricultural Science, 15, 387–394, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021859600006821, 1925.

Hanssens, D., Delefortrie, S., De Pue, J., Van Meirvenne, M., and De Smedt, P.: Frequency-Domain Electromagnetic Forward and Sensitivity Modeling: Practical Aspects of Modeling a Magnetic Dipole in a Multilayered Half-Space, IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Magazine, 7, 74–85, https://doi.org/10.1109/MGRS.2018.2881767, 2019.

Hbirkou, C., Welp, G., Rehbein, K., Hillnhütter, C., Daub, M., Oliver, M. A., and Pätzold, S.: The effect of soil heterogeneity on the spatial distribution of Heterodera schachtii within sugar beet fields, Applied Soil Ecology, 51, 25–34, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2011.08.008, 2011.

Hendrickx, M. G. A., Vanderborght, J., Janssens, P., Bombeke, S., Matthyssen, E., Waverijn, A., and Diels, J.: Pooled error variance and covariance estimation of sparse in situ soil moisture sensor measurements in agricultural fields in Flanders, SOIL, 11, 435–456, https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-11-435-2025, 2025.

Henrion, M., Li, Y., Koganti, T., Bechtold, M., Jonard, F., Opfergelt, S., Vanacker, V., Van Oost, K., and Lambot, S.: Mapping and monitoring peatlands in the Belgian Hautes Fagnes: Insights from Ground-penetrating radar and Electromagnetic induction characterization, Geoderma Regional, 37, e00795, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geodrs.2024.e00795, 2024.

Ingeman-Nielsen, T. and Baumgartner, F.: CR1Dmod: A Matlab program to model 1D complex resistivity effects in electrical and electromagnetic surveys, Computers & Geosciences, 32, 1411–1419, 2006.

Jones, E., Hulme, P., Malone, B., Filippi, P., and McBratney, A.: Mapping soil properties and their impact on yield-combining Dual EM, gamma radiometrics, elevation and soil colour to select sampling sites to predict soil properties and investigate their impact on yield across the paddock, Grains Research Update, 49, https://grdc.com.au/resources-and-publications/grdc-update-papers (last access: 11 September 2025), 2020.

JRC: The State of Soil in Europe, European Soil Data Centre (ESDAC), https://esdac.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ESDB_Archive/eusoils_docs/other/EUR25186.pdf (last access: 1 October 2023), 2012.

Kang, J., Walter, F., Halter, T., Paitz, P., and Fichtner, A.: Soil slope monitoring with Distributed Acoustic Sensing under wetting and drying cycles, Earth Surf. Dynam., 13, 1133–1155, https://doi.org/10.5194/esurf-13-1133-2025, 2025.

Katona, T., Gilfedder, B. S., Frei, S., Bücker, M., and Flores-Orozco, A.: High-resolution induced polarization imaging of biogeochemical carbon turnover hotspots in a peatland, Biogeosciences, 18, 4039–4058, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-18-4039-2021, 2021.

Kaufmann, M. S., Klotzsche, A., van der Kruk, J., Langen, A., Vereecken, H., and Weihermüller, L.: Assessing soil fertilization effects using time-lapse electromagnetic induction, SOIL, 11, 267–285, https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-11-267-2025, 2025.

Kessouri, P., Furman, A., Huisman, J. A., Martin, T., Mellage, A., Ntarlagiannis, D., Bücker, M., Ehosioke, S., Fernandez, P., Flores-Orozco, A., Kemna, A., Nguyen, F., Pilawski, T., Saneiyan, S., Schmutz, M., Schwartz, N., Weigand, M., Wu, Y., Zhang, C., and Placencia-Gomez, E.: Induced polarization applied to biogeophysics: recent advances and future prospects, Near Surface Geophysics, 17, 595–621, https://doi.org/10.1002/nsg.12072, 2019.

Khatkar, A., Beucher, A., Koganti, T., Munkholm, L. J., and Lamandé, M.: Mapping basic properties of Danish sandy soils using on-the-go proximal sensors and terrain attributes, Geoderma Regional, 42, e00981, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geodrs.2025.e00981, 2025.

Kibblewhite, M. G., Ritz, K., and Swift, M. J.: Soil health in agricultural systems, Biological Sciences, 363, 685–701, 2008.

Klotzsche, A., Jonard, F., Looms, M. C., and Kruk, J. V. D.: Measuring soil water content with ground penetrating radar: a decade of progress, Vadose Zone Journal, 17, https://doi.org/10.2136/vzj2018.03.0052, 2018.

Koganti, T., Ghane, E., Martinez, L. R., Iversen, B. V., and Allred, B. J.: Mapping of Agricultural Subsurface Drainage Systems Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Imagery and Ground Penetrating Radar, Sensors, 21, https://doi.org/10.3390/s21082800, 2021.

Kuhl, A. S., Kendall, A. D., Dam, R. L. V., and Hyndman, D. W.: Quantifying soil water and root dynamics using a coupled hydrogeophysical inversion, Vadose Zone Journal, 17, https://doi.org/10.2136/vzj2017.08.0154, 2018.

Luchtenbelt, H., Doelman, J., Bos, A., Daioglou, V., Jägermeyr, J., Müller, C., Stehfest, E., and van Vuuren, D.: Quantifying food security and mitigation risks consequential to climate change impacts on crop yields, Environmental Research Letters, 20, 014001, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ad97d3, December 2024.

Mary, B., Iván, V., Meggio, F., Peruzzo, L., Blanchy, G., Chou, C., Ruperti, B., Wu, Y., and Cassiani, G.: Imaging of the electrical activity in the root zone under limited-water-availability stress: a laboratory study for Vitis vinifera, Biogeosciences, 20, 4625–4650, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-20-4625-2023, 2023.

McLachlan, P., Blanchy, G., and Binley, A.: EMagPy: Open-source standalone software for processing, forward modeling and inversion of electromagnetic induction data, Computers & Geosciences, 146, 104561, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2020.104561, 2021.

Mendoza Veirana, G. M., Grison, H., Verhegge, J., Cornelis, W., and De Smedt, P.: Exploring the link between cation exchange capacity and magnetic susceptibility, SOIL, 11, 629–637, https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-11-629-2025, 2025.

Michels, V., Weigand, M., Lärm, L., Muller, O., and Kemna, A.: Non-Invasive Phenotyping of Sugar Beet and Maize Roots Using Field-Scale Spectral Electrical Impedance Tomography, Plant, Cell & Environment, 48, 7588–7604, https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.70049, 2025.

Moser, C., Binley, A., and Orozco, A. F.: 3D electrode configurations for spectral induced polarization surveys of landfills, Waste Management, 169, 208–222, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2023.07.006, 2023.

Obour, P. B. and Ugarte, C. M.: A meta-analysis of the impact of traffic-induced compaction on soil physical properties and grain yield, Soil and Tillage Research, 211, 105019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2021.105019, 2021.

O'Leary, D., Brogi, C., Brown, C., Tuohy, P., and Daly, E.: Linking electromagnetic induction data to soil properties at field scale aided by neural network clustering, Frontiers in Soil Science, 4, https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoil.2024.1346028, 2024.

O'Leary, D., Tuohy, P., Fenton, O., Healy, M. G., Pierce, H., Shnel, A., and Daly, E.: Assessing the impact of rewetting agricultural fen peat soil via open drain damming: an agrogeophysical approach, EGUsphere [preprint], https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2025-1966, 2025a.

O'Leary, D., Brown, C., Hodgson, J., Connolly, J., Gilet, L., Tuohy, P., Fenton, O., and Daly, E.: Airborne radiometric data for digital soil mapping of peat at broad and local scales, Geoderma, 453, 117129, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2024.117129, 2025b.

Pasquet, S., Bodet, L., Bergamo, P., Gurin, R., Martin, R., Mourgues, R., and Tournat, V.: Small-scale seismic monitoring of varying water levels in granular media, Vadose Zone Journal, 15, https://doi.org/10.2136/vzj2015.11.0142, 2016.

Peruzzo, L., Werban, U., Pohle, M., Pavoni, M., Mary, B., Cassiani, G., Consoli, S., and Vanella, D.: High-resolution frequency-domain electromagnetic mapping for the hydrological modeling of an orange orchard, SOIL, 11, 811–831, https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-11-811-2025, 2025.

Plattner, A. M.: GPRPy: Open-source ground-penetrating radar processing and visualization software, The Leading Edge, 39, 332–337, 2020.

Pretty, J. N., Brett, C., Gee, D., Hine, R. E., Mason, C. F., Morison, J. I. L., Raven, H., Rayment, M. D., and van der Bijl, G.: An assessment of the total external costs of UK agriculture, Agricultural Systems, 65, 113–136, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0308-521X(00)00031-7, 2000.

Preza-Fontes, G., Christianson, L. E., and Pittelkow, C. M.: Investigating tradeoffs in nitrogen loss pathways using an environmental damage cost framework, Agricultural & Environmental Letters, 8, e20103, https://doi.org/10.1002/ael2.20103, 2023.

Pulido-Moncada, M., Petersen, S. O., and Munkholm, L. J.: Soil compaction raises nitrous oxide emissions in managed agroecosystems. A review, Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 42, 1–26, 2022.

Rentschler, T., Werban, U., Ahner, M., Behrens, T., Gries, P., Scholten, T., Teuber, S., and Schmidt, K.: 3D mapping of soil organic carbon content and soil moisture with multiple geophysical sensors and machine learning, Vadose Zone Journal, 19, e20062, https://doi.org/10.1002/vzj2.20062, 2020.

Revil, A., Coperey, A., Shao, Z., Florsch, N., Fabricius, I. L., Deng, Y., Delsman, J., Pauw, P., Karaoulis, M., de Louw, P. G. B., Baaren, E. S. van, Dabekaussen, W., Menkovic, A., and Gunnink, J. L.: Complex conductivity of soils, Water Resources Research, 53, 7121–7147, 2017.

Romero-Ruiz, A., Linde, N., Keller, T., and Or, D.: A Review of Geophysical Methods for Soil Structure Characterization, Reviews of Geophysics, 56, 672–697, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018RG000611, 2018.

Romero-Ruiz, A., Linde, N., Baron, L., Solazzi, S. G., Keller, T., and Or, D.: Seismic Signatures Reveal Persistence of Soil Compaction, Vadose Zone Journal, 20, e20140, https://doi.org/10.1002/vzj2.20140, 2021.

Romero-Ruiz, A., Linde, N., Baron, L., Breitenstein, D., Keller, T., and Or, D.: Lasting effects of soil compaction on soil water regime confirmed by geoelectrical monitoring, Water Resources Research, 58, e2021WR030696, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021WR030696, 2022.

Romero-Ruiz, A., O'Leary, D., Daly, E., Tuohy, P., Milne, A., Coleman, K., and Whitmore, A. P.: An agrogeophysical modelling framework for the detection of soil compaction spatial variability due to grazing using field-scale electromagnetic induction data, Soil Use and Management, 40, e13039, https://doi.org/10.1002/vzj2.20140, 2024.

Rouze, G. S., Morgan, C. L. S., McBratney, A. B., and Neely, H. L.: Exploratory Assessment of Aerial Gamma Radiometrics across the Conterminous United States, Soil Science Society of America Journal, 81, 94–108, https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2016.07.0206, 2017.

Rücker, C., Günther, T., and Wagner, F. M.: pyGIMLi: An open-source library for modelling and inversion in geophysics, Computers & Geosciences, 109, 106–123, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2017.07.011, 2017.

Sanderman, J., Hengl, T., and Fiske, G. J.: Soil carbon debt of 12,000 years of human land use, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114, 9575–9580, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1706103114, 2017.

Solazzi, S. G., Bodet, L., Holliger, K., and Jougnot, D.: Surface-Wave Dispersion in Partially Saturated Soils: The Role of Capillary Forces, Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 126, e2021JB022074, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JB022074, 2021.

Stein, L. Y. and Klotz, M. G.: The nitrogen cycle, Current Biology, 26, R94–R98, 2016.

Swindles, G. T., Morris, P. J., Mullan, D. J., Payne, R. J., Roland, T. P., Amesbury, M. J., Lamentowicz, M., Turner, T. E., Gallego-Sala, A., Sim, T., Barr, I. D., Blaauw, M., Blundell, A., Chambers, F. M., Charman, D. J., Feurdean, A., Galloway, J. M., Gałka, M., Green, S. M., Kajukało, K., Karofeld, E., Korhola, A., Lamentowicz, Ł., Langdon, P., Marcisz, K., Mauquoy, D., Mazei, Y. A., McKeown, M. M., Mitchell, E. A. D., Novenko, E., Plunkett, G., Roe, H. M., Schoning, K., Sillasoo, Ü., Tsyganov, A. N., van der Linden, M., Väliranta, M., and Warner, B.: Widespread drying of European peatlands in recent centuries, Nature Geoscience, 12, 922–928, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-019-0462-z, 2019.

Tsukanov, K. and Schwartz, N.: Modeling Plant Roots Spectral Induced Polarization Signature, Geophysical Research Letters, 48, e2020GL090184, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL090184, 2021.

Van Dijk, M., Morley, T., Rau, M. L., and Saghai, Y.: A meta-analysis of projected global food demand and population at risk of hunger for the period 2010–2050, Nature Food, 2, 494–501, 2021.

Vereecken, H., Amelung, W., Bauke, S. L., Bogena, H., Brüggemann, N., Montzka, C., Vanderborght, J., Bechtold, M., Blöschl, G., Carminati, A., Javaux, M., Konings, A. G., Kusche, J., Neuweiler, I., Or, D., Steele-Dunne, S., Verhoef, A., Young, M., and Zhang, Y.: Soil hydrology in the Earth system, Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 3, 573–587, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-022-00324-6, 2022

von Hebel, C., Reynaert, S., Pauly, K., Janssens, P., Piccard, I., Vanderborght, J., van der Kruk, J., Vereecken, H., and Garré, S.: Toward high-resolution agronomic soil information and management zones delineated by ground-based electromagnetic induction and aerial drone data, Vadose Zone Journal, 20, e20099, https://doi.org/10.1002/vzj2.20099, 2021.

Wang, P., Hu, Z., Zhao, Y., and Li, X.: Experimental study of soil compaction effects on GPR signals, Journal of Applied Geophysics, 126, 128–137, 2016.

Wang, Y., Ying, H., Yin, Y., Zheng, H., and Cui, Z.: Estimating soil nitrate leaching of nitrogen fertilizer from global meta-analysis, Science of The Total Environment, 657, 96–102, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.029, 2019.

Weisser, W. W., Roscher, C., Meyer, S. T., Ebeling, A., Luo, G., Allan, E., Beßler, H., Barnard, R. L., Buchmann, N., Buscot, F., Engels, C., Fischer, C., Fischer, M., Gessler, A., Gleixner, G., Halle, S., Hildebrandt, A., Hillebrand, H., de Kroon, H., Lange, M., Leimer, S., Roux, X. L., Milcu, A., Mommer, L., Niklaus, P. A., Oelmann, Y., Proulx, R., Roy, J., Scherber, C., Scherer-Lorenzen, M., Scheu, S., Tscharntke, T., Wachendorf, M., Wagg, C., Weigelt, A., Wilcke, W., Wirth, C., Schulze, E.-D., Schmid, B., and Eisenhauer, N.: Biodiversity effects on ecosystem functioning in a 15-year grassland experiment: Patterns, mechanisms, and open questions, Basic and Applied Ecology, 23, 1–73, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2017.06.002, 2017.

Wu, K. and Lambot, S.: Analysis of Low-Frequency Drone-Borne GPR for Root-Zone Soil Electrical Conductivity Characterization, IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 60, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2022.3198431, 2022.

Wu, K., Rodriguez, G. A., Zajc, M., Jacquemin, E., Clément, M., Coster, A. D., and Lambot, S.: A new drone-borne GPR for soil moisture mapping, Remote Sensing of Environment, 235, 111456, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2019.111456, 2019.

Zreda, M., Shuttleworth, W. J., Zeng, X., Zweck, C., Desilets, D., Franz, T., and Rosolem, R.: COSMOS: the COsmic-ray Soil Moisture Observing System, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 16, 4079–4099, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-16-4079-2012, 2012.