the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Digging deeper: assessing soil quality in a diversity of conservation agriculture practices

Manon S. Ferdinand

Brieuc F. Hardy

Philippe V. Baret

Conservation Agriculture (CA) aims to enhance soil quality through three main principles: minimizing mechanical soil disturbance, maximizing soil organic cover, and diversifying crop species. However, the diversity of practices within CA makes the effect on soil quality hardly predictable. In this study, an evaluation of soil quality in CA fields across Wallonia (Belgium) was conducted for four distinct CA-types. Three soil quality indicators were examined: the soil structural stability, the soil organic carbon : clay ratio (SOC : Clay), and the labile carbon fraction (POXC). Results revealed significant variations among CA-types. The CA-type characterized by substantial temporary grassland and tillage-extensive crops (e.g., cereals, meslin, rape, flax) in the crop sequence had the highest soil structural stability, SOC : Clay ratio and POXC content. In contrast, the CA-type characterized by strict non-inversion tillage practices and frequent tillage-intensive crops (e.g., sugar beet, chicory, potatoes, carrots) had the lowest scores for the three indicators. Temporary grassland in the crop sequence appeared as the most influential factor improving soil quality. These findings highlight the need to consider the diversity of CA-types when evaluating the agronomic and environmental performance of CA systems, whose response depends on local soil and climatic conditions, the farming system, and the specific combination of practices implemented.

- Article

(1656 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(709 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Soils play a crucial role in supporting food production systems and providing ecosystem services, which promote agricultural system sustainability and resilience to climate change (Baveye et al., 2020; Weil and Brady, 2017). Soil quality is defined as the soil's capacity to perform multiple functions, such as supporting plant growth by the retention of water and the recycling of nutrients, storing carbon, and preserving water quality by filtration or degradation of contaminants. These functions, essential to human and ecosystem health, can be assessed through the analysis of soil chemical, physical, and biological parameters (Bongiorno et al., 2019; Doran and Parkin, 1994). However, soil quality is deteriorating and threatened (FAO and ITPS, 2015; IPCC, 2019). In the European Union, 62 % of soils are affected by at least one soil degradation process (EUSO, 2024). This is due to increased pressure on the land to support human infrastructures and activities, and also to unsustainable farming practices (Mason et al., 2023).

Conservation Agriculture (CA) has been proposed as an alternative farming system capable of achieving sustainable productivity while limiting soil degradation and improving soil quality (Chabert and Sarthou, 2020; Thierfelder et al., 2017). CA is based on three agronomic principles (or pillars) applied simultaneously: (i) minimizing mechanical soil disturbance by limiting the number and intensity of tillage operations, (ii) maximizing soil organic cover, and (iii) maximizing crop species diversification.

Reducing mechanical soil disturbance can result in the accumulation of organic matter (OM) in the topsoil (Chervet et al., 2016; Dimassi et al., 2014), which in turn can lead to improvements in several critical soil attributes. First, OM increases the stability of soil aggregates, which may decrease risks of soil erosion, and improve water infiltration and water availability for crops (Busari et al., 2015; FAO, 2019; Giller et al., 2009; González-Sánchez et al., 2017; Hobbs et al., 2008; Pisante et al., 2015). Additionally, the increase in OM in topsoil horizons may affect positively soil fertility, and in turn, productivity of some crops (González-Sánchez et al., 2017; Pisante et al., 2015).

The increase of soil cover by plants or crop residues serves as a physical shield against the erosivity of rainfall, mitigating aggregate disruption, soil crusting and surface runoff, therefore improving infiltration rates (Busari et al., 2015; González-Sánchez et al., 2017; Hobbs et al., 2008) and reducing erosion (Giller et al., 2009; Kassam et al., 2018; Pisante et al., 2015; Soane et al., 2012). Additionally, soil cover increases soil organic carbon (SOC) inputs and storage (Chenu et al., 2019) and promotes soil-dwelling fauna, such as earthworms, which, through their subterranean burrowing activities, further augment water infiltration (González-Sánchez et al., 2017).

Crop species diversification through the integration of plants with varied root structures contributes to the development of an extensive network of root canals and a larger pore connectivity (Jabro et al., 2021), which may result in more efficient water and nutrient uptake and therefore increase crop productivity in some cases (Bahri et al., 2019; González-Sánchez et al., 2017). Moreover, incorporating plants with deep and strong taproots (e.g. Brassicaceae such as mustard, radish, and turnip) mitigates soil compaction by penetrating compacted layers, creating root voids and channels once decomposed (Hamza and Anderson, 2005; Jabro et al., 2021). Additionally, species diversification enriches the overall diversity of soil biota, enhancing pest and disease control and facilitating nutrient recycling (Hobbs et al., 2008; Meena and Jha, 2018). These biological processes, driven by roots and earthworms, may effectively substitute the mechanical action of plowing (Chen and Weil, 2010), playing a crucial role in regenerating and maintaining soil structure.

Although CA represents a promising avenue to improve the sustainability of intensive agricultural systems, many technical challenges and knowledge gaps remain. Compared to conventional or organic agriculture, CA and its impact on soil quality have been poorly studied. CA practices are context-specific, and therefore, the impact of CA on soil quality varies to a large extent, with limited insight into the underlying mechanisms (Chabert and Sarthou, 2020; Chenu et al., 2019). The extent and significance of CA's impact on soil quality are known to fluctuate according to factors such as soil texture, climatic conditions, and specific CA practices (Chervet et al., 2016; Lahmar, 2010; Page et al., 2020). For instance, reduced tillage may occasionally increase soil compaction during a transition period, impeding both water infiltration and root growth (Pisante et al., 2015; Van den Putte et al., 2012).

Scant research has been conducted to assess CA systems that fully integrate all three principles (Adeux et al., 2022; Bohoussou et al., 2022). Many studies have primarily focused on comparing no-till and residue incorporation (e.g., chopped cereal straws) with conventional tillage and residue export, often overlooking the broader range of CA practices and particularly crop diversification (Page et al., 2020). However, soil quality is expected to improve the most when the three CA system's principles are associated and implemented together due to interactive and synergistic effects (Adeux et al., 2022; Chenu et al., 2019; Page et al., 2020). Therefore, on-farm studies of agricultural systems integrating the three principles of CA practices are critical to evaluate the amenities and performance of CA systems without bias.

One current issue is the lack of a clear definition of CA (Ferdinand, 2024; Sumberg and Giller, 2022). As a result, a diversity of practices exists within CA systems (Ferdinand and Baret, 2024), depending on local soil and climate conditions, the cropping context, and farmer economic and technical constraints (e.g., access to specific machinery). The CA principles are therefore often incompletely implemented. Accordingly, the impact of CA on soil quality, as well as other benefits associated with the cropping system (e.g., crop productivity), depend on the specific CA practices implemented (Craheix et al., 2016; Cristofari et al., 2017; Scopel et al., 2013).

In recent years, a significant number of farms showed an interest in CA practices in Wallonia, southern Belgium. In particular, no-till or reduced tillage showed promising results for decreasing erosion risk in intensive arable cropping systems (Vanwindekens and Hardy, 2023). So far, in 2021, 191 CA farms have been identified in Wallonia, representing 1.5 % of Walloon farms and covering an estimated 5 % of Walloon utilized agricultural area (Ferdinand, 2024). In a previous study, Ferdinand and Baret (2024) analyzed the diversity of practices within CA systems. They proposed a classification of CA-types according to the degree of implementation of each of the three CA principles. The categorization of CA-types highlights the diversity of cropping systems on CA farms, and helps to understand the relationship between a farm's productive orientation, the extent to which CA practices are implemented, and soil quality metrics.

Three reference CA-types were identified, controlled by three main factors: (i) the presence of temporary grassland in the crop sequence, (ii) the proportion of tillage-intensive crops (e.g., potatoes and beets), and (iii) the organic certification status (Ferdinand and Baret, 2024). CIO (Cash crops (i.e., annual crops grown to be sold for profit), tillage-Intensive crops, Organic) comprises organic farmers with a significant proportion of tillage-intensive crops. CIN (Cash crops, tillage-Intensive crops, Non-organic) includes non-organic farmers with a significant proportion of tillage-intensive crops. And GEM (temporary Grasslands, tillage-Extensive, Mixed) groups farmers (organic and non-organic) with a significant proportion of temporary grassland and tillage-extensive crops (e.g., winter cereals and rapeseed) in their crop sequence. Two intermediate groups (Ig) were also defined. The crop sequence of Ig1 farmers is characterized by a significant proportion of tillage-intensive crops, whereas some farmers also cultivate temporary grassland. Ig2 farmers grow mainly tillage-extensive crops without incorporating temporary grassland into their crop sequence (Ferdinand and Baret, 2024).

In this work, we aimed to assess how soil quality responds to different CA-types, and to identify CA practices that influence soil quality the most. To meet these goals, soil quality was investigated in a field network cultivated according to CA principles for at least five years in Wallonia, Belgium. To assess soil quality, three indicators were determined: (i) soil structural stability was measured by the QuantiSlakeTest (QST) method (Vanwindekens and Hardy, 2023), which provides an estimation of soil erodibility and resistance to compaction; (ii) the SOC : Clay ratio was used as an indicator of the organic status of soil and of the resilience of soil structural quality (Johannes et al., 2017); and (iii) the content of labile carbon was estimated by oxidation with 0.02 M permanganate (Culman et al., 2012), as a proxy of soil biological activity. Our working assumption was that reduced soil disturbance, longer soil cover, and cultivation of temporary grassland in the crop rotation are the main drivers of soil quality in CA systems.

2.1 Study area

The study was conducted in Wallonia (16 900 km2), the southern region of Belgium, characterized by an oceanic temperate climate. From northwest to southeast, precipitation increases (800 to 1400 mm) along with elevation (180 to 690 m) and a decrease in mean annual temperature (11 to 7.5 °C) (Chartin et al., 2017; SPW ARNE et al., 2024). In the same direction, a gradient in soil types spans from deep sand and silt loam soils completely free of rocks to shallow stony soils developed on schists, shales, or sandstones. Accordingly, agriculture shifts from very intensive arable cropping systems in the silt loam region (Vanwindekens and Hardy, 2023) to more extensive cattle breeding systems on shallow soils (Chartin et al., 2017; Goidts, 2009). Agricultural land covers 44 % of Wallonia's area (738 927 ha), with 35 % of permanent grassland, 24 % cereals, 21 % forage crops, and 14 % of industrial crops (Statbel, 2023). Organic farming extends over 12 % of Walloon cultivated areas (Apaq-W and Biowallonie, 2023).

2.2 Field surveys

2.2.1 CA Field selection

Twenty-eight farmers cultivating according to CA principles for more than five years were identified. In each farm, one field was selected for sampling based on the following criteria: (i) Sown with winter cereals (Triticum aestivum L.), spelt (Triticum spelta L.), einkorn wheat (Triticum monococcum L.), rye (Secale cereale L.), triticale (Triticosecale Wittm. ex A. Camus) or winter barley (Hordeum vulgare L.), including malting barley sown in winter; (ii) Accessible by car; (iii) With a maximum slope of 10 %; and (iv) Representative and relatively homogeneous in terms of soil type and SOC content.

2.2.2 Collection of CA practices

Each farmer was interviewed to collect their CA farming practices. Relevant information regarding the three principles of CA (soil disturbance, soil cover, and crop diversification) was collected to document the fifteen variables (five per pillar) needed to classify the field within the CA-types of Ferdinand and Baret (2024):

-

Mechanical soil disturbance is characterized by: (i) the frequency of tillage operations (named “Wheel Traffic”), (ii) the proportion of seeding operations compared to other tillage operations (“Seeding”), (iii) the frequency of use of powered tools (“Powered”), (iv) the frequency of use of plowing tools (“Plowing”), and (v) the plowing depth (“Plowing Depth”). To avoid confusion, we define “tillage” as any mechanical operation that fragments the soil, and “plowing” as a mechanical operation that inverts the soil horizons.

-

Soil organic cover is defined by: (i) the number of days the soil is covered by dead (e.g., crop residues, decaying leaves or manure) or living (e.g., annual crops, temporary grasslands or cover crops) mulch (“Total Cover”), (ii) the cover by living mulch only (“Living Cover”), (iii) the cover by temporary grassland (“Grassland Cover”), (iv) the soil cover during the erosion risk period (“ERP Cover”), and (v) the proportion of days when spring crops cover the soil during the ERP (“Spring Crops ERP Cover”).

-

Crop diversification is defined by: (i) the total number of species grown (i.e., annual main crops (A), temporary grassland (T), and cover crops) (“Total Species”), (ii) the number of short-term income crop species (“A+T Species”), (iii) the crop associations in A and T (“A+T Associations”), (iv) the mix of varieties in A and T (“A+T Mixes”), and (v) the number of tillage-intensive crops (“Tillage-intensive Crops”). Tillage-intensive crops are spring-sown crops that require deep soil preparation, a thin seedbed, and/or late harvesting, which often degrade soil structure. In Wallonia, these crops include sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.), chicory (Cichorium intybus L.), potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.), carrots (Daucus carota), onions (Allium cepa L.), maize (Zea mays L.), vegetables such as peas (Pisum sativum L.), beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), etc. In contrast, tillage-extensive crops include cereals (other than maize), meslin, rapeseed (Brassica napus L.), flax (Linum usitatissimum L.), etc.

2.2.3 Classification of CA-types

Farming practices were analyzed to classify them within one of the CA-types described by Ferdinand and Baret (2024). Briefly, the method classifies CA practices by an archetypal analysis combined with a hierarchical clustering analysis (Ferdinand and Baret, 2024). As a result, eleven fields fell into the CIN type, three within the GEM type, three within Ig1, and four within Ig2. Seven fields were not assigned to any CA-type, as archetypal analysis – while improving the identification of distinct practices – typically leaves a substantial share of practices unclassified, even when complemented by hierarchical clustering to reduce this proportion (Ferdinand and Baret, 2024).

2.2.4 Soil sampling

Soils were sampled from November 2021 to February 2022 in a one-hectare area within the selected fields and positioned at least ten meters from the field's edges. Sampling occurred at least two weeks after the last operation (e.g., sowing).

In each field, six 100 cm3 structured soil samples were randomly collected with steel Kopecky cylinders at a depth of 2–7 cm to measure soil structural stability. Soils were transported within the cylinders and carefully unmolded in the laboratory, sometimes after one or two days of air drying to limit sample disturbance.

For the determination of chemical soil properties, four composite samples were taken from each field. Each composite sample was bulked from five samples collected with a gouge auger from 0 to 30 cm in depth. The five samples were gently disaggregated by hand and carefully mixed in a bucket. About 1 L of fresh soil was kept for analysis.

2.3 Soil analysis

All samples were dried at room temperature for at least one week, then gently ground and sieved to 2 mm. The < 2 mm fraction was used to determine chemical soil properties. Before analysis, samples were further air-dried to constant weight. The weight of residual water was eliminated (ISO11465/1193, Association Française de Normalisation, 1993). Soil dry matter content was determined by drying about 1 g of soil at 105 °C overnight, then cooling the samples in a desiccator before weighing. Dry matter content was then used to correct the SOC and POXC contents.

2.3.1 General soil properties

Granulometry was analyzed by the Centre Provincial de l'Agriculture et de la Ruralité (CPAR) in La Hulpe (Belgium). Briefly, granulometry (clay [<2 µm], silt [2–50 µm], and sand [50–2000 µm] contents) was determined by sedimentation and sieving, according to Stokes law, by a method derived from the norm NF-X31-107:2003 (Association Française de Normalisation, 2003). Total C and N content were determined by dry combustion (vario MAX, © Elementar, MOCA, UCLouvain, Belgium). Inorganic carbon content was determined after a reaction with HCl in a closed chamber with a calcimeter working with an electronic pressure sensor (Sherrod et al., 2002). Inorganic carbon was subtracted from total C to obtain the soil organic carbon (SOC) content. Additional soil analyses (pH, exchangeable cations, CEC, and related measurements) were conducted but not detailed in the main text. These analyses are described in Sect. S1 of the Supplement.

The SOC : Clay ratio was calculated as the ratio between SOC and clay contents, expressed as dimensionless quantity (%SOC %clay). The SOC : Clay ratio has double interest. First, it indicates the organic status and carbon storage potential of soil (Prout et al., 2020; Pulley et al., 2023). Second, it indicates the soil's ability to develop a stable structure (Johannes et al., 2017; Vanwindekens and Hardy, 2023). In this work, the threshold values of 1 : 8 (good potential structural stability), 1 : 10 (moderate potential structural stability), and 1 : 13 (structural instability), proposed by Johannes et al. (2017), were used to classify the soil according to an expected level of soil structural resilience.

2.3.2 Permanganate oxidizable carbon

Permanganate oxidizable carbon (POXC) constitutes a labile sub-pool of SOC, defined as the carbon oxidized by 0.02 M potassium permanganate (KMnO4) (Huang et al., 2021). POXC was measured following Culman et al. (2012): 2.5 g of soil were incubated in 20 mL of 0.02 M KMnO4 for 10 min, and POXC was calculated from the remaining MnO concentration, determined by spectrophotometry at 550 nm. The labile SOC fraction was expressed as the ratio of POXC to SOC contents (POXC : SOC) and used as an indicator of nutrient cycling, soil structure, and microbial activity associated with soil degradation or restoration (Bongiorno et al., 2019; Weil et al., 2003).

2.3.3 Soil structural stability

Soil structural stability was measured by the QST method (Vanwindekens and Hardy, 2023). Once removed from the Kopecky cylinders, structured soils were left to air-dry for at least 30 d. Structured soil sample were then introduced, supported by a metallic 8 mm mesh basket, into distilled water, and soil mass evolution under water was recorded for 15 min by continuously weighing basket's content (Vanwindekens and Hardy, 2023). The curves of soil mass evolution over time were then used to calculate soil structural stability indicators, e.g., total relative mass loss, disaggregation speed, or time to meet a particular threshold value of mass loss (Vanwindekens and Hardy, 2023). In a comparison with the tests of Le Bissonnais, Vanwindekens and Hardy (2023) associated the beginning of the QST curves mainly to slaking, while the end of the curve is more related to the resistance to clay dispersion and differential swelling. In this work, the relative soil weight at the end of the experiment (Wend, unitless [g g−1]) was used as a global indicator of soil structural stability under wet conditions. Results for other indicators obtained from the QST curves can be found in Sect. S2.

2.4 Data analysis

Data analysis focuses only on fields falling within one of the CA-types (excluding the seven unclassified fields), as our goal is to use CA-types as an entry point to assess the impact of CA on specific soil quality indicators. Additionally, two more fields were excluded from the analysis due to incomplete data. Therefore, the results from 19 fields out of 28 were analyzed. First, soil properties were analyzed according to CA practices, beyond the categorization of CA-types. Pearson correlations were calculated between the soil attributes and the variables used to categorize CA practices. Second, soil properties were analyzed according to CA-types. Nevertheless, the sample is not balanced, with an unequal distribution of farmers between CA-types (notably, the CIO type was not represented). Therefore, we used descriptive statistics to provide an overview of the observed trends between CA-types, deliberately avoiding the use of inferential statistics in this analysis. To explore the relationship between labile and total soil organic carbon, we plotted POXC against SOC, following the approach of Jensen et al. (2019). The Pearson correlation analysis was performed using the corrplot package (Wei et al., 2017), and the results were visualized with the ggplot2 R package (Tollefson, 2021). Data was analyzed using R-4.3.2 (R Core Team, 2022).

3.1 Soil properties

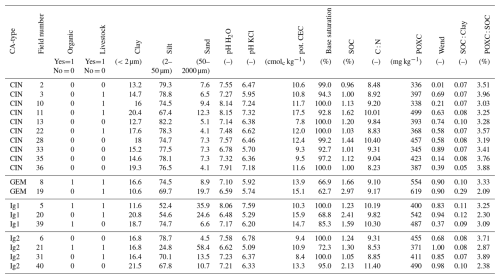

Table 1 displays the main soil properties of the experimental fields. Soil clay contents ranged from 10.6 % to 20.8 %, soil pH fluctuated between 6.48 and 8.15, pHKCl ranged from 5.09 to 7.59, potential CEC varied between 7.8 and 17.5 cmolc kg−1, and base saturation values were between 62.7 % and 100 %. SOC contents spanned from 0.96 % to 2.97 %, and POXC varied between 336 and 619 mg kg−1. Regarding the indicators, Wend values ranged from 0.01 to 1.00, SOC : Clay varied from 0.05 to 0.29, and POXC : SOC from 2.09 % to 3.96 %. The raw values for each sample are available in Sect. S3. Pearson correlation matrix of soil properties is presented in Sect. S4.

3.2 Correlation between soil properties and CA practices

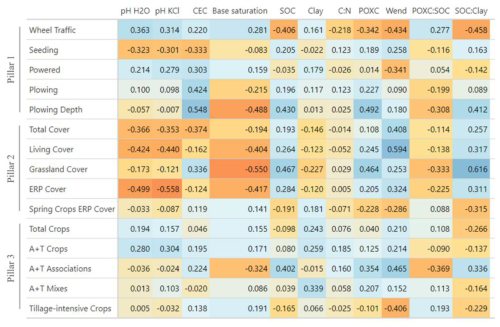

Table 2 presents Pearson correlations between the soil attributes and the variables used to categorize CA practices. None of the variables of farming practices correlated strongly with any of soil attributes (correlation coefficients systematically ), which indicates that the relationships between soil quality and farming practices are complex and multifactorial.

Table 2Pearson correlation coefficients between soil properties and CA practices. Legend: Annual crops (A), Erosion risk period (ERP), Temporary grassland (T).

Regarding the indicators of soil disturbance, wheel traffic correlates negatively with soil structural stability (Wend; ) and the SOC : Clay ratio (), whereas plowing depth positively correlates with the SOC : Clay ratio (r=0.41). Regarding the indicators of soil cover, both total and living cover correlated positively with soil structural stability (Wend; r=0.41 and 0.59). Temporary grassland cover correlated positively with the SOC : Clay ratio (r=0.62) but negatively with the POXC : SOC ratio (). Regarding crop diversification, crop association correlated positively with soil structural stability (Wend; r=0.47), in contrast to the occurrence of tillage-intensive crops that correlated negatively with soil structural stability (Wend; ).

The contents of SOC and POXC correlated more closely with CA practices than the POXC : SOC ratio did. Specifically, the SOC and POXC are more closely associated with wheel traffic ( and −0.34 compared to 0.28), plowing depth (r=0.43 and 0.49 compared to −0.31), grassland cover (r=0.47 and 0.46 compared to −0.33), and crop associations (r=0.40 and 0.35 compared to −0.37).

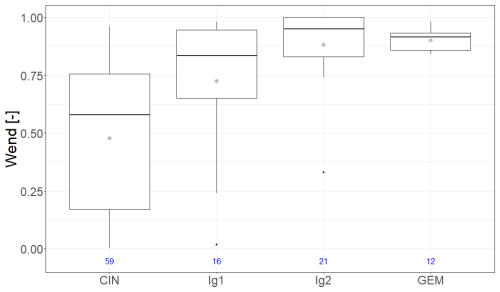

Figure 1Wend indicator calculated from QuantiSlakeTest curves for the four CA-types. Boxes show the median (thick line), average (grey diamond), and the number of individual samples per CA-type. Legend: Cash tillage-intensive crops non-organic farmers (CIN), temporary grassland and tillage-extensive crops with a mix of organic and non-organic farmers (GEM), intermediate group (Ig1 and Ig2).

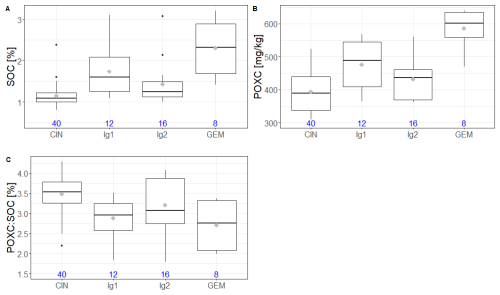

Figure 2(A) SOC contents, (B) POXC contents, and (C) POXC : SOC ratios across the four CA-types. Boxes show the median (thick line), average (grey diamond), and the number of individual samples per CA-type. Legend: Cash tillage-intensive crops non-organic farmers (CIN), temporary grassland and tillage-extensive crops with a mix of organic and non-organic farmers (GEM), intermediate group (Ig1 and Ig2).

3.3 Relationship between soil properties and CA types

3.3.1 Soil structural stability

Results of soil structural stability of the four CA-types are presented on Fig. 1. CIN samples had the lowest Wend values, indicating a smaller resistance to disaggregation in water than the other CA-types. The mean Wend values increased as follows: CIN ≪ Ig1 < Ig2 ≈ GEM. For further details on soil structural stability, the QST curves are displayed for different fields according to their respective CA-type (see Sect. S5).

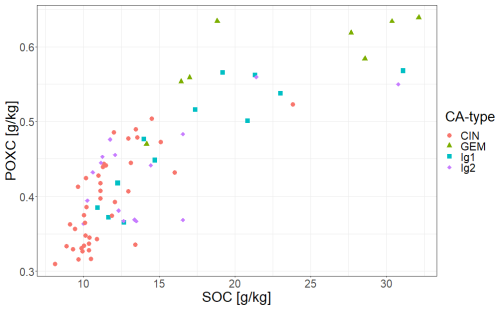

Figure 3Permanganate oxidizable carbon (POXC) as a function of soil organic content (SOC), according to the CA-types. Legend: Cash tillage-intensive crops non-organic farmers (CIN), temporary grassland and tillage-extensive crops with a mix of organic and non-organic farmers (GEM), intermediate group (Ig1 and Ig2).

3.3.2 Soil organic matter characteristics

The contents of SOC and POXC and the POXC : SOC ratio are presented by CA-types on Fig. 2. Contents of SOC and POXC follow a similar trend, with an increase in the order CIN ≈ Ig2 < Ig1 < GEM. Conversely, the POXC : SOC ratio increases in the opposite order (GEM ≈ Ig1 < Ig2 < CIN).

Although POXC is known to be partially sensitive to soil type (Culman et al., 2012), this effect appeared minimal in our dataset. The soils included in this study covered a relatively narrow range of textural classes, with clay content ranging from 11.6 % to 21.5 % (Table 1). Furthermore, we observed weak correlations between POXC and pH or granulometry fractions (see Sect. S4).

The relationship between POXC and SOC in Fig. 3 illustrates why the POXC fraction tends to decrease as SOC content increases. Initially, POXC levels rise rapidly with SOC levels, but the rate of increase gradually diminishes beyond approximately 0.6 g kg−1. This trend is notably pronounced in Ig1 and GEM fields.

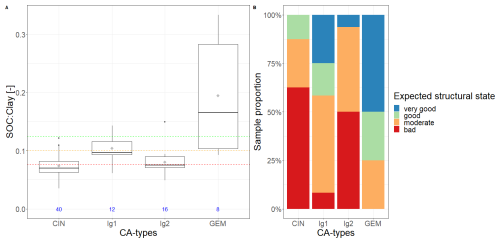

Figure 4(A) SOC : Clay ratio for each CA-type. Lines are SOC : Clay thresholds: Green = 1 : 8, orange = 1 : 10, red = 1 : 13. (B) Proportions of samples categorized by CA-type according to expected soil quality by SOC : Clay ratio, as defined by Johannes et al. (2017). Legend: Cash tillage-intensive crops non-organic farmers (CIN), temporary grassland and tillage-extensive crops with a mix of organic and non-organic farmers (GEM), intermediate group (Ig1 and Ig2).

3.3.3 The SOC : Clay ratio

While the Wend index reflects the actual stability of soil structure at the time of measurement, the SOC : Clay ratio provides complementary information on the soil's potential and resilience to form and maintain a stable structure. The fields were therefore classified according to threshold values of SOC : Clay ratios (1 : 13, 1 : 10, and 1 : 8) proposed by Johannes et al. (2017), corresponding to expected levels of soil structural (in)stability (Fig. 4). A significant proportion of CIN samples had SOC : Clay < 1 : 13 (i.e., depleted in SOC for their clay content), and a significant proportion of GEM samples had SOC : Clay ≥ (i.e., enriched in SOC for their clay content). The SOC : Clay ratios rose in the order CIN ≈ Ig2 < Ig1 ≪ GEM.

4.1 Soil structural stability in Conservation Agriculture beyond tillage

The soil of CA fields had a median structural stability value of 0.81 for the Wend indicator (Table 1), which is in line with average values (Wend=0.75, compared to 0.4 for plowed fields) observed in the topsoil of Luvisols under arable cropping managed with reduced tillage practices for 18 years in Wallonia (Vanwindekens and Hardy, 2023). This result is consistent with the reduction of soil mechanical disturbance for the fields under CA, although the comparison should be made cautiously, as the study of Vanwindekens and Hardy (2023) was conducted on a long-term field trial with a 2-year rotation (sugar beet – winter wheat) in the loess belt of Belgium, whereas the present study spans across several soil, agricultural and climatic contexts across the Walloon region. In particular, our dataset includes crop-livestock mixed farming systems with ley-arable rotation. In such systems, soil cover indicators have very high values, and OM inputs from ley and farmyard manure favor soil OM storage, which improves the overall resilience and stability of soil structure (in line with an increase in the SOC : Clay ratio). As a result, the use or non-use of a plow does not explain much of the variability in soil structural stability across the dataset. This relates to the common use of a plow for temporary grassland destruction, particularly in organic farming systems. This contrasts with studies comparing CA fields to a control under conventional farming in arable cropping systems (e.g., Mamedov et al., 2021), in which soil structure is less resilient to plowing because the OM content is generally low, due to limited organic inputs to soil (Vanwindekens and Hardy, 2023).

Among CA-types, the CIN (Cash crops, tillage-Intensive crops, Non-organic) group is the only one where all farmers systematically implement non-inversion tillage practices. These practices entail soil preparation through fragmentation, mixing and burial, without horizon inversion. However, CIN fields are more sensitive to soil disaggregation under water than Ig1, Ig2, and GEM types (Fig. 2), highlighting that soil structural stability is not only controlled by tillage, but also by other agronomic factors related to the other two pillars of CA. CIN group is characterized by a higher frequency of tillage-intensive crops and a lower soil cover compared to the other CA-types. These systems have a relatively low SOC : Clay ratio and, therefore, lower soil structural resilience. These results align with studies showing that soil quality benefits are greater when all CA pillars are implemented together (Adeux et al., 2022; Chenu et al., 2019; Page et al., 2020).

Interestingly, a positive correlation was identified between SOC content and plowing depth (Table 2). While this result may seem counterintuitive, it may reflect the specific management practices in certain CA-types, notably the mechanical destruction of temporary grassland by occasional plowing in the GEM group. Additionally, organic certification may further explain the positive correlation between plowing and SOC content. Organic farmers are more dependent on plowing to control weeds than conventional farmers, which may explain the higher frequency of full-inversion tillage in organic CA systems. However, fertilization in organic farms relies almost exclusively on organic inputs such as farmyard manure, which increases the return of OM to soil. This increases carbon inputs and improves SOC contents and stability (Chenu et al., 2019).

4.2 Soil quality variations in Conservation Agriculture driven by temporary grassland

Our measured POXC : SOC ratios (mean = 3.26 %) fall within the range reported in European studies (1.45 %–4.32 %; Bongiorno et al., 2019), in absence of specific references for Wallonia. Additionally, consistent with the findings of Jensen et al. (2019), we observed a decrease of the POXC : SOC ratio with SOC content (Fig. 3). Similar trends have previously been reported in pasture systems (Awale et al., 2017).

The highest values of SOC content (corresponding to lowest values of POXC : SOC) were measured in GEM and Ig1 fields, two groups with a ley-arable crop rotation. Accordingly, the absolute SOC content correlates positively with the occurrence of temporary grassland (Table 2). Carbon (C) input is recognized as the first driver controlling SOC storage (Derrien et al., 2023; Virto et al., 2012). The efficacy of temporary grasslands in storing SOC relates to high inputs of organic residues and the low C : N ratio of grass, which increases the relative anabolic use of C by microbes and thereby decreases the net SOC loss by microbial catabolism (Cotrufo et al., 2013; Liang et al., 2017). Beyond the total amount of C inputs, the quality of these inputs differs between cropland and grassland. Grassland receives approximately 1.4 times more organic carbon from root biomass compared to arable soils (Jacobs et al., 2020). The quality of C inputs – particularly the contribution of root-derived material – plays a role as critical as the amount of organic carbon input in shaping SOC stocks across land-use systems (Jacobs et al., 2020; Vanwindekens et al., 2024). These C inputs from the rhizosphere increase the labile, N-rich SOC fraction, which gradually contributes to enriching stable SOC stocks, dominated by mineral-associated SOC (Liang et al., 2017; van Wesemael et al., 2019).

The results also emphasized the key role of temporary grasslands in maintaining SOC contents above the threshold value of structural instability (Vertès et al., 2007). Indeed, the SOC : Clay ratio correlates positively with the occurrence of temporary grassland, but also correlates negatively with wheel traffic on the field (Table 2). As a result, fields with a SOC : Clay ratio < 1 : 13 (structural instability threshold) are absent from the GEM group, which counts a high proportion of soils > 1 : 10 in SOC : Clay (good structural quality) (Fig. 4; Dexter et al., 2008; Johannes et al., 2017; and Prout et al., 2020). In contrast, the CIN group, corresponding to intensive arable cropping systems with a high occurrence of tillage-intensive crops, shows the highest proportion of samples falling below the 1 : 10 threshold. These soils exhibit a high sensitivity to erosion and compaction, but also possess the potential to sequester organic carbon in complexed forms if soil management practices are adapted (Dexter et al., 2008).

Our findings are in line with recent studies indicating that the increase in SOC contents and carbon sequestration is primarily due to the other two principles of CA – soil organic cover and crop species diversification – achieved by increasing primary production through rotations and cover crops, increasing the biomass returned to the soil by crop residues and root material, and improving grassland management (Blanco-Canqui, 2024; Chenu et al., 2019). They also support the view that maintaining or achieving high SOC stocks is challenging in arable farming systems disconnected from animal husbandry. Indeed, in such systems temporary grassland is generally absent, crop succession has a high proportion of spring crops, and access to cattle manure may be limited.

4.3 Pros and cons of on-farm studies

One main strength of on-farm studies is that the cropping systems encompass the entire complexity of farming systems, which increases the credibility of the results for farmers and therefore the probability of adoption of innovative practices by peers. This approach contrasts with experiments conducted in controlled environments in research stations, such as long-term field experiments (LTE). LTEs enable the decoupling of factors by isolating agricultural practices and controlling various parameters studied to disentangle the individual effects of these practices. However, such experiments often inadequately represent on-farm field processes, as well as technical and economical constraints driving farmer's choices (Dupla et al., 2021, 2022). Interactions between agronomic factors may explain why findings from controlled experiments may differ substantially from those observed under on-farm conditions (Dupla et al., 2022). As an example, when tillage is considered individually in LTEs (Dimassi et al., 2014; Martínez et al., 2016), reduced tillage has a limited effect on SOC storage in the long-term compared to plowing in temperate regions. This contrasts with on-farm results, suggesting a positive impact of tillage reduction on SOC storage (Dupla et al., 2022). This discrepancy might relate to the time saved by not plowing, which allows for an earlier sowing of intercrops and therefore a larger amount of biomass returning to soil in the form of green manure. Another strength of our work is the effort provided to take the diversity of agricultural practices into account, which is rarely accounted for either within CA systems or in other farming systems (Riera et al., 2023).

On-farm studies are also restrictive in several ways. The main constraints are probably the poor control of field operations, alongside logistical constraints collecting samples and phytotechnical data over multiple years. For instance, the legacy of land use and practices before conversion to CA (e.g., from grassland to cropland) may still influence soil quality many years later. The large spatial extent of field networks also increases the range of soil and climate conditions, which may impact soil quality beyond farming practices (Chervet et al., 2016; Lahmar, 2010; Page et al., 2020). To assess the covariation between CA-type and climate conditions, a balanced sampling protocol would have been necessary. However, the GEM type appears more prevalent in southern Wallonia, while the CIN type predominantly occupies the northern part. In some respects, we are faced with a circularity as some practices are only present in certain soil types, and those soil types constrain the practices that can be implemented and affect the outcomes of these practices.

Nevertheless, we believe that the pros largely outweigh the cons to meet the objectives of our study. By documenting the effects of CA practices on soil quality through on-farm observations and by integrating the diversity of farmer-implemented practices within a single agricultural system, this work provides a realistic and systemic understanding of how CA is applied in practice in Wallonia and how it may affect soil quality.

In this work, we have taken on the challenge of assessing how the diversity of CA systems affects soil quality. Results revealed significant variations in soil quality among CA-types. Between the 15 variables used to classify CA systems, some proved to be decisive for soil quality. Particularly, the occurrence of temporary grassland in GEM-type fields was strongly related to the organic status of the soil. As a result, the soil samples of this CA-type exhibited the best scores of soil structural stability, regardless of tillage practices. In contrast, CIN-type fields, characterized by a high proportion of tillage-intensive crops in the rotation (e.g., sugar beet, chicory, potatoes, carrots), had a relatively low SOC : Clay ratio and soil structural stability despite the strict abandonment of full-inversion tillage.

These findings highlight the need to move beyond simplistic dichotomies when evaluating the agronomic and environmental performance of CA systems, whose responses depend on local soil, crops, and climatic conditions, as well as on the specific combination of practices implemented. Our study also revealed that the most important factors for the control of soil quality (e.g., tillage, C inputs, occurrence of temporary grassland, tillage-intensive crops) are intimately linked to (i) the productive orientation of the farm and (ii) the organic certification. These two elements were also dominant in the definition of CA-types by Ferdinand and Baret (2024). This is not surprising because both factors largely influence crop rotations, cultivar choices, and associated soil management practices, which, in turn, control soil quality. To refine the results of this work, a comparison between CA versus conventional farms from the same productive orientation, and within the same soil and climatic region, would be appropriate to assess the specific benefits of CA.

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| C | carbon |

| CA | Conservation Agriculture |

| CEC | cation exchange capacity |

| OM | organic matter |

| POXC | permanganate oxidizable carbon |

| QST | QuantiSlakeTest |

| SOC | soil organic carbon |

Data are available in Table S3 of the Supplement (additional Excel file).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-12-79-2026-supplement.

MSF: conceptualization, investigation, data curation, methodology, formal analysis, visualization, writing (original draft preparation). BFH: writing (review and editing), conceptualization, validation. PVB: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, validation, funding acquisition, writing (review and editing).

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Our first thanks go obviously to the farmers for their trust, their time, and their sharing. Without them, this research would not have been possible. The choice of measurements and the interpretation of the results were carried out with the help of several contributors: Yannick Agnan (UCL/ELI), Pierre Bertin (UCL/ELI), Frédéric Vanwindekens (CRA-W), Marie-Hélène Jeuffroy (INRAE), Aubry Vandeuren (UCL/ELI), Lola Leveau (UCL/ELI), Caroline Chartin (CRA-W), Maxime Thomas (UCL/ELI), Bas van Wesemaele (UCL/ELI), Klara Dvorakova (UCL/ELI) and Frédéric Gaspart (UCL/ELI). Thanks again to them for their time and ideas. Thanks to students Gabrielle Dubois, Charles Son, and Sami Royer for their help in collecting and analyzing the samples. This research involved a series of measurements in the laboratory, and therefore the invaluable help of several people including Karine Hénin (UCL/ELI), Elodie Devos (UCL/ELI), Marco Bravin (UCL), and the Centre Provincial de l'Agriculture et de la Ruralité (CPAR) in La Hulpe. Thanks also to Antoine Soetewey (UCL/ISBA) and Catherine Rasse (UCL/SMCS) for their advice on data analysis. Finally, we have used ChatGPT and DeepL Write to improve the readability of some text passages at the end of the writing process.

This research was funded by the UCLouvain, the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique – F.R.S – FNRS – Fonds pour la Formation à la Recherche dans l'Industrie et dans l'Agriculture-FRIA, and by the Chaire en Agricultures nouvelles of Baillet Latour Fund.

This paper was edited by Luis Merino-Martín and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Adeux, G., Guinet, M., Courson, E., Lecaulle, S., Munier-Jolain, N., and Cordeau, S.: Multicriteria assessment of conservation agriculture systems, Frontiers in Agronomy, 4, https://doi.org/10.3389/fagro.2022.999960, 2022.

Apaq-W and Biowallonie: Les chiffres du bio 2022 en Wallonie, Collaboration entre l'Apaq-W et Biowallonie, https://www.biowallonie.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/ChiffresDuBio-2022-BD.pdf (last access: 15 January 2026), 2023.

Association Française de Normalisation: ISO 11465:1993, https://www.iso.org/fr/standard/20886.html (last access: 15 January 2026), 1993.

Association Française de Normalisation: Qualité du sol – Détermination de la distribution granulométrique des particules du sol – Méthode à la pipette, Standard NF-X31-107, 2003.

Awale, R., Emeson, M. A., and Machado, S.: Soil Organic Carbon Pools as Early Indicators for Soil Organic Matter Stock Changes under Different Tillage Practices in Inland Pacific Northwest, Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 5, https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2017.00096, 2017.

Bahri, H., Annabi, M., Cheikh M'Hamed, H., and Frija, A.: Assessing the long-term impact of conservation agriculture on wheat-based systems in Tunisia using APSIM simulations under a climate change context, Science of the Total Environment, 692, 1223–1233, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.307, 2019.

Baveye, P. C., Schnee, L. S., Boivin, P., Laba, M., and Radulovich, R.: Soil Organic Matter Research and Climate Change: Merely Re-storing Carbon Versus Restoring Soil Functions, Frontiers in Environmental Science, 8, https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2020.579904, 2020.

Blanco-Canqui, H.: Assessing the potential of nature-based solutions for restoring soil ecosystem services in croplands, Science of The Total Environment, 921, 170854, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.170854, 2024.

Bohoussou, Y. N., Kou, Y.-H., Yu, W.-B., Lin, B., Virk, A. L., Zhao, X., Dang, Y. P., and Zhang, H.-L.: Impacts of the components of conservation agriculture on soil organic carbon and total nitrogen storage: A global meta-analysis, Science of The Total Environment, 842, 156822, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156822, 2022.

Bongiorno, G., Bünemann, E. K., Oguejiofor, C. U., Meier, J., Gort, G., Comans, R., Mäder, P., Brussaard, L., and de Goede, R.: Sensitivity of labile carbon fractions to tillage and organic matter management and their potential as comprehensive soil quality indicators across pedoclimatic conditions in Europe, Ecological Indicators, 99, 38–50, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.12.008, 2019.

Busari, M. A., Kukal, S. S., Kaur, A., Bhatt, R., and Dulazi, A. A.: Conservation tillage impacts on soil, crop and the environment, International Soil and Water Conservation Research, 3, 119–129, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iswcr.2015.05.002, 2015.

Chabert, A. and Sarthou, J.-P.: Conservation agriculture as a promising trade-off between conventional and organic agriculture in bundling ecosystem services, Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 292, 106815, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2019.106815, 2020.

Chartin, C., Stevens, A., Goidts, E., Krüger, I., Carnol, M., and van Wesemael, B.: Mapping Soil Organic Carbon stocks and estimating uncertainties at the regional scale following a legacy sampling strategy (Southern Belgium, Wallonia), Geoderma Regional, 9, 73–86, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geodrs.2016.12.006, 2017.

Chen, G. and Weil, R. R.: Penetration of cover crop roots through compacted soils, Plant Soil, 331, 31–43, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-009-0223-7, 2010.

Chenu, C., Angers, D. A., Barré, P., Derrien, D., Arrouays, D., and Balesdent, J.: Increasing organic stocks in agricultural soils: Knowledge gaps and potential innovations, Soil and Tillage Research, 188, 41–52, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2018.04.011, 2019.

Chervet, A., Ramseier, L., Sturny, W. G., Zuber, M., Stettler, M., Weisskopf, P., Zihlmann, U., Martínez, G. I., and Keller, T.: Rendements et paramètres du sol après 20 ans de semis direct et de labour, Recherche Agronomique Suisse, 7, 216–223, 2016.

Cotrufo, M. F., Wallenstein, M. D., Boot, C. M., Denef, K., and Paul, E.: The Microbial Efficiency-Matrix Stabilization (MEMS) framework integrates plant litter decomposition with soil organic matter stabilization: do labile plant inputs form stable soil organic matter?, Global Change Biology, 19, 988–995, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12113, 2013.

Craheix, D., Angevin, F., Doré, T., and de Tourdonnet, S.: Using a multicriteria assessment model to evaluate the sustainability of conservation agriculture at the cropping system level in France, European Journal of Agronomy, 76, 75–86, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2016.02.002, 2016.

Cristofari, H., Girard, N., and Magda, D.: Supporting transition toward conservation agriculture: a framework to analyze the learning processes of farmers, Hungarian Geographical Bulletin, 66, 65–76, https://doi.org/10.15201/hungeobull.66.1.7, 2017.

Culman, S. W., Snapp, S. S., Freeman, M. A., Schipanski, M. E., Beniston, J., Lal, R., Drinkwater, L. E., Franzluebbers, A. J., Glover, J. D., Grandy, A. S., Lee, J., Six, J., Maul, J. E., Mirsky, S. B., Spargo, J. T., and Wander, M. M.: Permanganate Oxidizable Carbon Reflects a Processed Soil Fraction that is Sensitive to Management, Soil Science Society of America Journal, 76, 494–504, https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2011.0286, 2012.

Derrien, D., Barré, P., Basile-Doelsch, I., Cécillon, L., Chabbi, A., Crème, A., Fontaine, S., Henneron, L., Janot, N., Lashermes, G., Quénéa, K., Rees, F., and Dignac, M.-F.: Current controversies on mechanisms controlling soil carbon storage: implications for interactions with practitioners and policy-makers. A review, Agron. Sustain. Dev., 43, 21, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-023-00876-x, 2023.

Dexter, A. R., Richard, G., Arrouays, D., Czyż, E. A., Jolivet, C., and Duval, O.: Complexed organic matter controls soil physical properties, Geoderma, 144, 620–627, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2008.01.022, 2008.

Dimassi, B., Mary, B., Wylleman, R., Labreuche, J., Couture, D., Piraux, F., and Cohan, J.-P.: Long-term effect of contrasted tillage and crop management on soil carbon dynamics during 41 years, Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 188, 134–146, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2014.02.014, 2014.

Doran, J. W. and Parkin, T. B.: Defining and Assessing Soil Quality, in: Defining Soil Quality for a Sustainable Environment, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 1–21, https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaspecpub35.c1, 1994.

Dupla, X., Gondret, K., Sauzet, O., Verrecchia, E., and Boivin, P.: Changes in topsoil organic carbon content in the Swiss leman region cropland from 1993 to present. Insights from large scale on-farm study, Geoderma, 400, 115125, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2021.115125, 2021.

Dupla, X., Lemaître, T., Grand, S., Gondret, K., Charles, R., Verrecchia, E., and Boivin, P.: On-Farm Relationships Between Agricultural Practices and Annual Changes in Organic Carbon Content at a Regional Scale, Front. Environ. Sci., 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.834055, 2022.

EUSO: EUSO Soil Health Dashboard, https://esdac.jrc.ec.europa.eu/esdacviewer/euso-dashboard/, last access: 13 December 2024.

FAO: Three principles of Conservation Agriculture, http://www.fao.org/conservation-agriculture/en/, last access: 6 December 2019.

FAO and ITPS: Status of the World's Soil Resources (SWSR) – Main Report, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and Intergovernmental Technical Panel on Soils, Rome, Italy, https://www.fao.org/3/i5199e/i5199e.pdf (last access: 15 January 2026), 2015.

Ferdinand, M.: The diversity of practices in conservation agriculture, Thesis, UCLouvain, http://hdl.handle.net/2078.1/287412 (last access: 15 January 2026), 2024.

Ferdinand, M. S. and Baret, P. V.: A method to account for diversity of practices in Conservation Agriculture, Agron. Sustain. Dev., 44, 31, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-024-00961-9, 2024.

Giller, K. E., Witter, E., Corbeels, M., and Tittonell, P.: Conservation agriculture and smallholder farming in Africa: The heretics' view, Field Crops Research, 114, 23–34, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2009.06.017, 2009.

Goidts, E.: Soil organic carbon evolution at the regional scale: overcoming uncertainties & quantifying driving forces, UCLouvain, http://hdl.handle.net/2078.1/21726 (last access: 15 January 2026), 2009.

González-Sánchez, E. J., Moreno-Garcia, M., Kassam, A., Holgado-Cabrera, A., Trivino-Tarradas, P., Carbonell-Bojollo, R., Pisante, M., Veroz-Gonzalez, O., and Basch, G.: Conservation Agriculture: Making Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Real in Europe, European Conservation Agriculture Federation (ECAF), 182 pp., https://ecaf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Conservation_Agriculture_climate_change_report.pdf (last access: 15 January 2026), 2017.

Hamza, M. A. and Anderson, W. K.: Soil compaction in cropping systems: A review of the nature, causes and possible solutions, Soil and Tillage Research, 82, 121–145, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2004.08.009, 2005.

Hobbs, P. R., Sayre, K., and Gupta, R.: The role of conservation agriculture in sustainable agriculture, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 363, 543–555, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2007.2169, 2008.

Huang, J., Rinnan, Å., Bruun, T. B., Engedal, T., and Bruun, S.: Identifying the fingerprint of permanganate oxidizable carbon as a measure of labile soil organic carbon using Fourier transform mid-infrared photoacoustic spectroscopy, European Journal of Soil Science, 72, 1831–1841, https://doi.org/10.1111/ejss.13085, 2021.

IPCC: Summary for Policymakers – Special Report on Climate Change and Land, https://www.ipcc.ch/srccl/chapter/summary-for-policymakers/ (last access: 15 January 2026), 2019.

Jabro, J. D., Allen, B. L., Rand, T., Dangi, S. R., and Campbell, J. W.: Effect of Previous Crop Roots on Soil Compaction in 2 Yr Rotations under a No-Tillage System, Land, 10, 202, https://doi.org/10.3390/land10020202, 2021.

Jacobs, A., Poeplau, C., Weiser, C., Fahrion-Nitschke, A., and Don, A.: Exports and inputs of organic carbon on agricultural soils in Germany, Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst., 118, 249–271, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10705-020-10087-5, 2020.

Jensen, J. L., Schjønning, P., Watts, C. W., Christensen, B. T., Peltre, C., and Munkholm, L. J.: Relating soil C and organic matter fractions to soil structural stability, Geoderma, 337, 834–843, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2018.10.034, 2019.

Johannes, A., Matter, A., Schulin, R., Weisskopf, P., Baveye, P. C., and Boivin, P.: Optimal organic carbon values for soil structure quality of arable soils. Does clay content matter?, Geoderma, 302, 14–21, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2017.04.021, 2017.

Kassam, A., Friedrich, T., and Derpsch, R.: Global spread of Conservation Agriculture, International Journal of Environmental Studies, 76, 29–51, https://doi.org/10.1080/00207233.2018.1494927, 2018.

Lahmar, R.: Adoption of conservation agriculture in Europe: Lessons of the KASSA project, Land Use Policy, 27, 4–10, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2008.02.001, 2010.

Liang, C., Schimel, J. P., and Jastrow, J. D.: The importance of anabolism in microbial control over soil carbon storage, Nat. Microbiol., 2, 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.105, 2017.

Mamedov, A. I., Fujimaki, H., Tsunekawa, A., Tsubo, M., and Levy, G. J.: Structure stability of acidic Luvisols: Effects of tillage type and exogenous additives, Soil and Tillage Research, 206, 104832, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2020.104832, 2021.

Martínez, I., Chervet, A., Weisskopf, P., Sturny, W. G., Etana, A., Stettler, M., Forkman, J., and Keller, T.: Two decades of no-till in the Oberacker long-term field experiment: Part I. Crop yield, soil organic carbon and nutrient distribution in the soil profile, Soil and Tillage Research, 163, 141–151, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2016.05.021, 2016.

Mason, E., Cornu, S., and Chenu, C.: Stakeholders' point of view on access to soil knowledge in France. What are the opportunities for further improvement?, Geoderma Regional, 35, e00716, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geodrs.2023.e00716, 2023.

Meena, R. P. and Jha, A.: Conservation agriculture for climate change resilience: A microbiological perspective, in: Microbes for Climate Resilient Agriculture, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 165–190, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119276050.ch8, 2018.

Page, K. L., Dang, Y. P., and Dalal, R. C.: The Ability of Conservation Agriculture to Conserve Soil Organic Carbon and the Subsequent Impact on Soil Physical, Chemical, and Biological Properties and Yield, Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 4, https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2020.00031, 2020.

Pisante, M., Stagnari, F., Acutis, M., Bindi, M., Brilli, L., Di Stefano, V., and Carozzi, M.: Conservation agriculture and climate change, in: Conservation Agriculture, Springer International Publishing, 579–620, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-11620-4_22, 2015.

Prout, J. M., Shepherd, K. D., McGrath, S. P., Kirk, G. J. D., and Haefele, S. M.: What is a good level of soil organic matter? An index based on organic carbon to clay ratio, European Journal of Soil Science, 72, 2493–2503, https://doi.org/10.1111/ejss.13012, 2020.

Pulley, S., Taylor, H., Prout, J. M., Haefele, S. M., and Collins, A. L.: The soil organic carbon: Clay ratio in North Devon, UK: Implications for marketing soil carbon as an asset class, Soil Use and Management, 39, 1068–1081, https://doi.org/10.1111/sum.12920, 2023.

R Core Team: R: The R Project for Statistical Computing, https://www.r-project.org/ (last access: 15 January 2026), 2022.

Riera, A., Duluins, O., Schuster, M., and Baret, P. V.: Accounting for diversity while assessing sustainability: insights from the Walloon bovine sectors, Agron. Sustain. Dev., 43, 30, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-023-00882-z, 2023.

Scopel, E., Triomphe, B., Affholder, F., Da Silva, F. A. M., Corbeels, M., Xavier, J. H. V., Lahmar, R., Recous, S., Bernoux, M., Blanchart, E., de Carvalho Mendes, I., and De Tourdonnet, S.: Conservation agriculture cropping systems in temperate and tropical conditions, performances and impacts. A review, Agron. Sustain. Dev., 33, 113–130, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-012-0106-9, 2013.

Sherrod, L. A., Dunn, G., Peterson, G. A., and Kolberg, R. L.: Inorganic Carbon Analysis by Modified Pressure-Calcimeter Method, Soil Science Society of America Journal, 66, 299–305, https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2002.2990, 2002.

Soane, B. D., Ball, B. C., Arvidsson, J., Basch, G., Moreno, F., and Roger-Estrade, J.: No-till in northern, western and south-western Europe: A review of problems and opportunities for crop production and the environment, Soil and Tillage Research, 118, 66–87, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2011.10.015, 2012.

SPW ARNE, DEMNA, and DEE: Environnement physique: Etat de l'environnement wallon : Indicateurs environnementaux, http://etat.environnement.wallonie.be/contents/indicatorcategories/composantes-environnementales-et/environnement-physique.html (last access: 15 January 2026), 2018.

Statbel: Chiffres clés de l'agriculture 2023, https://doc.statbel.fgov.be/publications/S510.01/S510.01F_Chiffres_cle_agri_2023.pdf (last access: 15 January 2026), 2023.

Sumberg, J. and Giller, K. E.: What is “conventional” agriculture?, Global Food Security, 32, 100617, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2022.100617, 2022.

Thierfelder, C., Chivenge, P., Mupangwa, W., Rosenstock, T. S., Lamanna, C., and Eyre, J. X.: How climate-smart is conservation agriculture (CA)? – its potential to deliver on adaptation, mitigation and productivity on smallholder farms in southern Africa, Food Security, 9, 537–560, 2017.

Tollefson, M. (Ed.): Graphics with the ggplot2 Package: An Introduction, in: Visualizing Data in R 4: Graphics Using the base, graphics, stats, and ggplot2 Packages, Apress, Berkeley, CA, 281–293, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4842-6831-5_7, 2021.

Van den Putte, A., Govers, G., Diels, J., Langhans, C., Clymans, W., Vanuytrecht, E., Merckx, R., and Raes, D.: Soil functioning and conservation tillage in the Belgian Loam Belt, Soil and Tillage Research, 122, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2012.02.001, 2012.

van Wesemael, B., Chartin, C., Wiesmeier, M., von Lützow, M., Hobley, E., Carnol, M., Krüger, I., Campion, M., Roisin, C., Hennart, S., and Kögel-Knabner, I.: An indicator for organic matter dynamics in temperate agricultural soils, Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 274, 62–75, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2019.01.005, 2019.

Vanwindekens, F., Lamotte, L. de, Serteyn, L., Goidts, E., Doncel, A., Chartin, C., Hardy, B., Leclercq, V., Smissen, H. V. D., and Huyghebaert, B.: Principes généraux pour maintenir – voire améliorer – le taux de matière organique dans les sols agricoles - Document d'orientation des agriculteurs et des agricultrices souhaitant souscrire à la MAEC-Sols en Wallonie, https://gitrural.cra.wallonie.be/portail-public/documents-u07/-/raw/main/doc_orientation_maec_sols.pdf (last access: 15 January 2026), 2024.

Vanwindekens, F. M. and Hardy, B. F.: The QuantiSlakeTest, measuring soil structural stability by dynamic weighing of undisturbed samples immersed in water, SOIL, 9, 573–591, https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-9-573-2023, 2023.

Vertès, F., Hatch, D., Velthof, G., Taube, F., Laurent, F., Loiseau, P., and Recous, S.: Short-term and cumulative effects of grassland cultivation on nitrogen and carbon cycling in ley-arable rotations, in: Grassland Science in Europe, Vol. 12, 227–246, https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/20083018734 (last access: 15 Januar 2026), 2007.

Virto, I., Barré, P., Burlot, A., and Chenu, C.: Carbon input differences as the main factor explaining the variability in soil organic C storage in no-tilled compared to inversion tilled agrosystems, Biogeochemistry, 108, 17–26, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-011-9600-4, 2012.

Wei, T., Simko, V., Levy, M., Xie, Y., Jin, Y., and Zemla, J.: Package “corrplot”, Statistician, 56, 18, https://peerj.com/articles/9945/Supplemental_Data_S10.pdf (last access: 15 January 2026), 2017.

Weil, R. R. and Brady, N. C.: The Nature and Properties of Soils, 15th edn., https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301200878_The_Nature_and_Properties_of_Soils_15th_edition (last access: 15 January 2026), 2017.

Weil, R. R., Islam, K. R., Stine, M. A., Gruver, J. B., and Samson-Liebig, S. E.: Estimating active carbon for soil quality assessment: A simplified method for laboratory and field use, American Journal of Alternative Agriculture, 18, 3–17, https://doi.org/10.1079/AJAA200228, 2003.