the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Long-term pig manure application increases SOC through aggregate protection and Fe-C associations in a subtropical red soil (Udic Ferralsols)

Hui Rong

Zhangliu Du

Weida Gao

Lixiao Ma

Xinhua Peng

Yuji Jiang

Demin Yan

Manure is known to improve soil organic carbon (SOC) in Fe-rich red soils, but the underlying stabilization mechanisms remain poorly understood. A long-term field experiment was conducted with four treatments: no amendment (Control), low manure (LM, 150 kg N ha−1 yr−1), high manure (HM, 600 kg N ha−1 yr−1), and high manure with lime (HML, 600 kg N ha−1 yr−1 plus 3000 kg Ca (OH)2 ha−1 (3 yr)−1). The quantity and quality of SOC were characterized by physical fractionation, 13C NMR spectroscopy and thermogravimetry (TG) analysis from 0–20 cm depth. 18 year manure application increased total SOC by 65.1 %–126.7 %, with the increase primarily occurring in the particulate organic matter (POM) fraction. Specifically, POM C increased substantially by 208 %–592 %, compared to a 32.0 %–66.8 % increase in MAOM C. POM C was stabilized through the process of hierarchical aggregation. Fresh manure inputs acted as binding nuclei, leading to an increase in macroaggregates (>0.25 mm) concurrently with a reduction in microaggregates (0.05–0.25 mm), physically isolating labile C from microbial decomposition. Concurrently, manure amendments triggered Fe-mediated chemical stabilization. The elevated pH (4.8 to 5.4–7.1) in the manure treatments enhanced non-crystalline Fe oxide (Feo) content by 25.4 %, which positively correlated with MAOM C (R2 = 0.56, P<0.05). Despite chemical composition shift toward aliphaticity and reduced aromaticity, thermally stable organic matters increased by 8 %–12 %, revealing the critical role of Feo in offsetting inherent molecular lability when aggregate protection was removed by destruction prior to TG analysis. Overall, this study proposes a dual SOC stabilization framework via physical and chemical Fe-carbon associations in a subtropical red soil.

- Article

(2022 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(391 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Soil organic carbon (SOC), the largest carbon reservoir in the terrestrial ecosystems, plays critical roles in climate mitigation and soil multifunctionality (Amelung et al., 2020; Lal, 2004). Red soils (Udic Ferralsols, according to Chinese Soil Taxonomy) have low SOC content due to intense weathering and rapid mineralization in tropical and subtropical South China (Yan et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013). While manure has been widely used to enhance SOC in these soils (Bai et al., 2023; Nichitha et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023), the underlying mechanisms governing its stabilization remain elusive. Currently, the discrepancies existed regarding the manure-induced SOC accrual through chemical recalcitrance, physical protection (by aggregation processes), or organo-mineral interactions – given the Fe-enrich red soils and their pH-dependent reactivity (Kleber et al., 2021; Six et al., 2002; Song et al., 2022). Considering the red soils covering 22 % of China's cropland and low inherent SOC levels, it is essential to unveil Fe-C interactions that regulate SOC stabilization through organic amendments.

Existing studies showed some conflicting evidences on SOC stabilization pathways. For instance, Mustafa et al. (2021) reported increased aromatic C (chemically recalcitrant) with manure application, whereas Yan et al. (2013) observed preferential accumulation of labile O-alkyl C. This paradox highlighted uncertainties on how manure inputs altered SOC composition. It is reported that Fe oxides contributed to SOC stabilization in red soils (Zhang et al., 2013). These reactive Fe phases can form stable covalent bonds between their surface hydroxyls and organic functional groups, protecting SOC from microbial decomposition (Ruiz et al., 2024). In comparison with crystalline Fe oxides (Fed), non-crystalline Fe oxides (Feo) exhibit organic matter adsorption capacity primarily attributed to their larger specific surface area (Zhang et al., 2013). Previous studies have demonstrated that long-term application of organic fertilizers – including manure, compost, and straw – significantly increased non-crystalline iron oxides (Feo) in agricultural soils (Chen et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019). These studies further revealed that redox cycling promoted the reductive dissolution of crystalline iron (Fed), followed by its reprecipitation as amorphous Feo during oxidative periods. On the other hand, soil pH was identified as a key factor dynamically influencing the ratio (Liu et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2023). Although organic amendments are known to elevate pH in acidic red soils, the specific effect of soil pH modulating the formation and stabilization of Feo remains unclear. Additionally, previous studies widely isolated chemical recalcitrance, aggregation protection, or organo-mineral interactions separately, largely neglecting the integrative assessments including these pathways. To address this knowledge gap, an integrative approach combining physical fractionation, molecular characterization, and thermal stability analysis is essential for elucidating the coupled effects of manure on SOC quantity and quality.

Physically separating soil organic matter (SOM) into mineral-associated organic matter (MAOM) and particulate organic matter (POM) fractions could help to predict SOC dynamics, and clarify SOC stabilization mechanisms. The POM associated SOC (defined as POM C) physically protected in the macroaggregates, while MAOM associated SOC (defined as MAOM C) chemically protected via organo-mineral bonding (Chenu et al., 2019; Lavallee et al., 2019; Poeplau et al., 2018). Although physical fractionation could effectively isolate operationally defined these SOC pools (Poeplau et al., 2018), it failed to reveal the chemical heterogeneity of SOC (Cotrufo et al., 2019; Lavallee et al., 2019). Thus, solid-state 13C NMR spectroscopy could address this gap by quantifying SOC functional groups (e.g. alkyl, O-alkyl, aromatic C), after completely disrupting organo-mineral interaction by HF pretreatment (Kögel-Knabner, 1997). Additionally, the thermogravimetry (TG) could rapidly assess the thermal stability of SOC without requiring pretreatment (Gao et al., 2015). On the other hand, some advanced techniques such as nano-scale secondary ion mass spectrometry (Nano-SIMS) and high-resolution mass spectrometry could identify the spatial visualization of organo-mineral associations and molecular characterization, these approaches heavily required complex instrumentation and are not cost-effective for the comparative analysis of multiple samples. Therefore, combined NMR with TG approaches to efficiently evaluate the chemical composition and thermal stability of SOC in response to manure management.

The specific objectives of this study were: (1) to evaluate the changes of Fe oxides and its effect on MAOM formation; (2) to explore how soil aggregation affected POM formation; (3) to evaluate the effect of manure application on SOC composition and stability. We hypothesized that: (1) Manure application could enhance MAOM C formation by increasing non-crystalline Fe oxides (Feo), induced by elevated pH; (2) Manure application would strengthen the physical protection due to the improved soil aggregation, which triggered labile SOC protection; (3) The application of pig manure would boost the recalcitrance of SOC, thus the thermal stability.

2.1 Site description and experimental design

The long-term field experiment is located at Yingtan National Agroecosystem Field Experiment Station of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (28°15′20′′ N, 116°55′30′′ E) in Jiangxi Province, China. The site has a typically subtropical humid monsoon climate with a mean annual temperature of 17.6 °C and precipitation of 1795 mm (Jiang et al., 2018). The soil is derived from Quaternary red clay, and is classified as Udic Ferralsols according to Chinese Soil Taxonomy. The soil contains 36.3 % clay, 45.2 % silt and 21.2 % sand.

The field experiment was initiated in April 2002. The soils used in this experiment were transported from adjacent forestland and repacked (to a depth of 2 m) for all the plots. This design ensures a uniform initial soil condition and eliminates the influence of prior land use history. Four treatments were compared: (1) no manure amendment (Control), (2) low pig manure with 150 kg N ha−1 a−1 (LM), (3) high pig manure with 600 kg N ha−1 a−1 (HM), and (4) high pig manure with 600 kg N ha−1 a−1 and lime applied at 3000 kg Ca (OH)2 ha−1 (3 a)−1 (HML). The four treatments received solely pig manure as the nitrogen source, with no synthetic fertilizers applied. The pig manure, collected from nearby pig farms, contained an average total carbon of 386.5 g kg−1, total nitrogen of 36.2 g kg−1 and total phosphorus of 21.6 g kg−1 on a dry matter basis. The annual amount of pig manure applied to each treatment was calculated based on its nitrogen content. Since all aboveground residues (stalks and leaves) and manually recoverable roots were completely removed from the field after harvest, the total carbon inputs to the soil were derived mainly from pig manure. This resulted in average annual carbon inputs of around 1.6 and 6.4 Mg C ha−1 for the LM and HM treatments, respectively (see Supplement for calculation details). The field experiment was set up following a completely randomized design, with each treatment has three replicate plots. The field was planted with corn (Zea mays L.) monoculture annually from April to July. The pig manure was applied annually each April onto the soil surface (0–10 cm depth) and subsequently incorporated into the topsoil through plowing and harrowing. All the management measures, including sowing, harvesting and weeding, were manually operated.

2.2 Sampling

Sampling was conducted in July 2019, after the harvest of corn. Triplicate topsoil samples (0–20 cm) were randomly collected with a shovel from each plot and composited together to form one bulk sample. The soil samples were air-dried at room temperature and were gently crushed with a rubber mallet to pass through an 8 mm sieve, preserving aggregates >8 mm for further analysis. Visible plant residues, roots and stones were removed (Soil Survey Staff, 2011). No visible manure residues were observed.

2.3 Soil properties measurements

SOC and Total nitrogen (TN) were determined by an elemental analyzer (Vario MACRO, Elementar, Germany). Soil pH was measured using a glass electrode (PHS-3D, SANXIN, China) with soil : deionized water ratio of 1 : 2.5. Crystalline (Fed) and non-crystalline Fe oxides (Feo) were extracted by DCB (Dithionite-citrate-bicarbonate) and oxalate, respectively (Yan et al., 2013), and then were determined by graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry (GFAAS) (PinAAcle 900T, PerkinElmer, America). Water stability of aggregates was tested using the fast-wetting method following Le Bissonnais (1996). Aggregate stability was expressed as mean weight diameter (MWD). Detailed experimental processes and calculation can be found in Zhou et al. (2019).

2.4 Physical fractionation

Soil was fractionated into MAOM (<53 µm) and POM (> 53 µm) fraction following Cambardella and Elliott (1992) and Cotrufo et al. (2019). Briefly, 10 g sieved samples (< 2 mm) were dispersed in dilute sodium hexametaphosphate ((NaPO3)6, 0.5 %) at a soil : solution ratio of 1 : 4 by shaking for 18 h (25 °C, 180 r min−1). This procedure primarily disrupts macroaggregates (>250 µm), but remaining that stable microaggregates (<53 µm). After dispersing, soil slurry was passed through a 53 µm sieve and rinsed several times with deionized water. The fraction passing through the sieve was collected as MAOM fraction, and that remaining on the sieve was collected as POM fraction. Both fractions were centrifuged and the solution was decanted, and then the remaining material was oven-dried to constant weights at 60 °C. SOC concentration of each fraction was measured using the wet oxidation method. Dried mass proportions of each fraction (g fraction g−1 soil) were calculated as follows:

where fM and fP were the dried mass proportions of MAOM and POM fraction (g fraction g−1 bulk soil), respectively; mM and mP (g) were the dried masses of MAOM and POM fractions; mbulk (g) was the dried mass of bulk soil.

SOC in the MAOM and POM fractions were called as MAOM C and POM C, respectively in this paper. MAOM C and POM C were calculated by multiplying the dried mass proportions of each fraction (g fraction g−1 soil) by the respective SOC concentrations (g C kg−1 fraction) as follows (Garten and Wullschleger, 2000; Lian et al., 2015):

where fM and fP were calculated by Eqs. (1) and (2); SOCM and SOCP were the SOC concentrations in the MAOM and POM fraction (g C kg−1 fraction), respectively.

The contributions of MAOM C and POM C to total SOC (%) was calculated as:

where MAOM C and POM C were derived from Eqs. (3) and (4), respectively; total SOC was the content of SOC in the bulk soil.

2.5 SOC chemical composition and chemical stability

SOC chemical composition was analyzed with a solid-state cross-polarization magic angle spinning (CPMAS) 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. Prior to NMR analysis, <2 mm air-dried soils were pretreated with hydrofluoric acid (HF) to remove paramagnetic Fe3+ (iron oxides) following Gao et al. (2021). While HF pretreatment can dissolve short-range-order minerals and potentially disrupt certain organo-mineral associations, it is an essential step to improve the signal-to-noise ratio and spectral resolution required for the reliable quantification of carbon functional groups. Firstly, 20 g soil was mixed with 100 mL 10 % () HF solution in a polyethylene bottle and then shaken for 0.5 h d−1 for three days. Afterwards, the supernatant liquid was discarded and another 100 mL 10 % HF solution was added again. The above procedures were repeated for 15 times. The residue was rinsed 10 times with deionized water until the pH was close to neutral. The remaining soil was freeze-dried and then ground in an agate mortar to pass through a 100-mesh sieve (0.149 mm) for further analysis. This fine grinding ensured homogeneous packing in the NMR rotor, minimizing signal heterogeneity (Simpson and Simpson, 2012).

Carbon functional groups were determined with the Bruker Ascend 500 MHz NMR spectrometer (Bruker BioSpin, Rheinstetten, Germany). Dry powdered samples were placed in a 4 mm sample rotor operating at a 13C resonance frequency of 125.8 MHz. The NMR spectrometer run at a spinning rate of 5 kHz, and 10 500 scans were collected for each sample. The spectra were collected over an acquisition time of 12 ms and a recycle delay of 0.8 s. All obtained spectra were processed with phase and baseline corrections. To allow for a direct comparison of the relative distribution of carbon functional groups, the total spectral intensity of each spectrum was normalized to that of the Control soil sample. The normalized spectra were then integrated across and we assigned the obtained spectra to four different carbon functional groups, i.e., alkyl C (0–45 ppm), O-alkyl C (45–110 ppm), aromatic C (110–160 ppm) and carbonyl C (160–220 ppm) according to Kögel-Knabner (1997). The relative concentrations of the different functional groups were calculated as the percentage of their peak areas to the total aeras using MestReNova 14.0 software (Mestrelab Research, 2019, Spain). Indices used to evaluate SOC recalcitrance include: alkyl C O-alkyl C, aromaticity, aromatic C O-alkyl C, aliphatic C aromatic C and aliphaticity (Baldock et al., 1997; Du et al., 2017). Aromaticity = aromatic C (alkyl C + O-alkyl C + aromatic C); Aliphatic C = alkyl C + O-alkyl C; Aliphaticity = (alkyl C + O-alkyl C) (alkyl C + O-alkyl C + aromatic C). The alkyl C O-alkyl C ratio reflects the degree of microbial transformation, with higher values indicating advanced decomposition and accumulation of recalcitrant alkyl compounds (Baldock et al., 1997). The aromatic C O-alkyl C ration aligns with the alkyl C O-alkyl C ration in reflecting the degree of SOC decomposition, whereas the aliphatic C aromatic C ratio presents a contrary perspective to them. Aromaticity is a chemical concept denoting the resistance to microbial degradation (Kögel-Knabner, 1997). Aliphaticity is used to quantify the proportion of labile aliphatic components relative to stable aromatic moieties.

2.6 Thermogravimetry analysis

TG analysis was performed using a Netzsch TG 209F1 (Netzsch-Gerätebau GmbH, Selb, Germany). Air-dried soil samples were first sieved through a 2 mm mesh, and then ground in a ball mill to pass through a 50 µm sieve. The grounded soil samples (5–10 mg) were placed in an Al2O3 crucible covered with an aluminum lid and were oxidized in an atmosphere of 20 mL min−1 of synthetic air (20 % O2 and 80 % N2) and 20 mL min−1 of N2 as a protective gas. The temperature program included a heating rate of 10 °C min−1 from 40 up to 800 °C. The sample mass percentage relative to the initial mass as a function of temperature was recorded simultaneously, and its first derivative (DTG) was calculated to represent the mass loss rate.

Three processes were detected in the temperature range of 40 to 800 °C: hygroscopic moisture evaporation, SOM decomposition and carbonate breaking down (Gao et al., 2015; Siewert, 2004). Based on the observed DTG curve, the weight loss between 180 and 530 °C, representing the temperature range during which SOM was decomposed, was defined as the total mass of SOM (Exotot). The mass loss between 180 and 380 °C was a consequence of thermally labile SOM oxidation (Exo1) and that between 380 and 530 °C was caused by the combustion of more stable organic matter (Exo2) (Gao et al., 2015; Volkov et al., 2020). We used two parameters, the ratio of Exo1 and Exotot (Exo1 Exotot) and the temperature at which half of the SOM was decomposed (TG-T50), to characterize the thermal stability of SOM. Higher Exo1 Exotot and lower TG-T50 values indicate that the sample has more thermally labile or unstable SOM (Gao et al., 2015; Siewert, 2004).

2.7 Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out with R Studio software (R Development Core Team, version 4.1.2). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to assess the effect of amendments on soil physico-chemical properties, SOC physical fractions, chemical composition and thermal indices. The independence of samples, normality of residuals and homogeneity of variances were checked by Chisq, Shapiro-Wilk and Bartlett test, respectively. Fisher's least significant difference (LSD) method was used for the multiple comparisons of means with a 0.05 significance level. Linear regression analysis was conducted to investigate the correlations between SOC and iron oxides, soil aggregation, and the relationships between pH and iron oxides. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to evaluate the relationship between the quantity and quality of SOC and factors related to chemical protection and physical protection. Pearson correlation analyses were performed to explore the relationships between chemical composition and thermal indices.

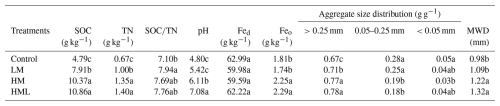

3.1 Long-term pig manure application increased SOC, TN, pH, non-crystalline (Feo) and improved soil aggregation

Long-term manure amendment altered the soil physico-chemical properties (Table 1). Relative to the Control, the SOC concentration was 64.9 %, 116.2 % and 126.6 % higher in the LM, HM and HML treatments, respectively (P<0.05), and TN concentration was 48.0 %–108.2 % higher (P<0.05). The pH values were 0.62–2.28 units higher than that in the Control (P<0.05). Application of pig manure had no significant effect on crystalline iron oxides (Fed) content (P>0.05), but the HM and HML treatments showed significantly greater non-crystalline iron oxides (Feo), with an increase of 25.4 % relative to the Control (P<0.05). Compared to the Control, the HM and HML treatments had significantly higher macroaggregates (>0.25 mm) content by 15.8 % and 16.8 %, respectively, and greater mean weight diameter (MWD) by 24.3 % and 35.0 % (P<0.05). In contrast, microaggregates (0.05–0.25 mm) was lower under the HM and HML treatments, with reduction of 30.4 % and 36.4 %, respectively (P<0.05).

Table 1Soil organic carbon (SOC), total nitrogen (TN), the ration of SOC to TN (SOC TN), pH, crystalline iron oxides (Fed), non-crystalline iron oxides (Feo), aggregate size distribution and mean weight diameter (MWD) of water-stable aggregates under no manure (Control), low manure (LM), high manure (HM) and high manure plus lime (HML) treatments.

Values are the means (n=3). Different lowercase letters after values in the same row indicate a significant difference among four manure treatments (P<0.05).

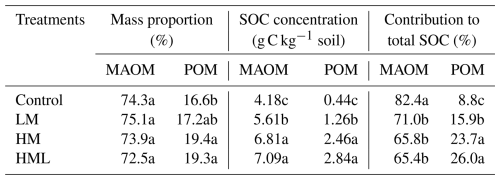

3.2 Long-term pig manure application affected SOM physical fractions: MAOM and POM

The distribution of MAOM and POM fractions was significantly influenced by manure and lime amendments (P<0.05, Table 2). Across all treatments, MAOM dominated the soil mass proportion (72.5 %–75.1 %), whereas the proportion of POM was progressively higher, ranging from 16.6 % in the Control to 19.3 %–19.4 % under the HM and HML treatments.

Table 2Mass proportion, SOC concentration and contribution of the mineral-associated organic matter (MAOM) (<53 µm) fraction, particulate organic matter (POM) (>53 µm) fraction under no manure (Control), low manure (LM), high manure (HM) and high manure plus lime (HML) treatments.

Values are the means (n=3). Different lowercase letters after values in the same row indicate a significant difference among four manure treatments (P<0.05). Calculations follow the methodology described in Sect. 2.4.

Manure application improved SOC concentration in both fractions. SOC in the MAOM fraction was 32.0 %–66.8 % greater, and that in the POM fraction was 208 %–592 % greater relative to the Control. The contribution of MAOM to total SOC was lower in the HM and HML treatments (65.5 %–65.8 %) than in the Control (82.4 %), while the contribution of POM was nearly threefold higher (increasing from 8.8 % to 23.7 %–26.0 %). Lime addition (HML vs. HM) did not significantly alter mass proportions but further enhanced POM C concentration (+15.4 %) and its contribution to total SOC (+9.7 %).

3.3 Effect of long-term pig manure application on SOC chemical composition and recalcitrance

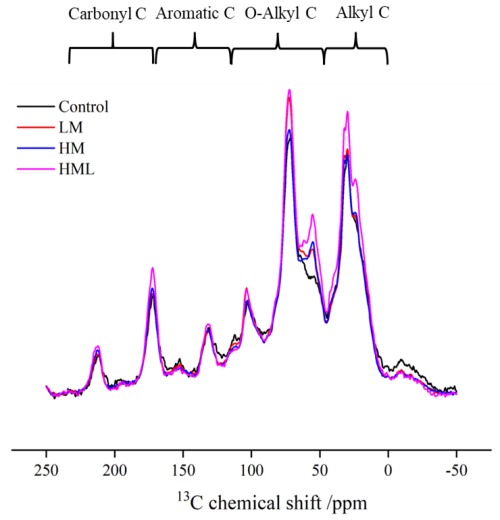

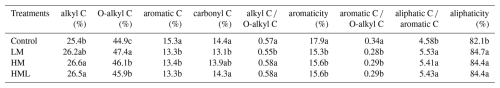

The solid-state 13C NMR spectra showed different signal patterns for the different treatments (Fig. 1) and quantified the ratios of the different SOC functional groups shown in Table 3. Relative to the Control, the HM and HML treatments had a significantly higher proportion of alkyl C by 4.6 %–4.9 % (P<0.05), while the LM treatment showed no significant difference (P>0.05). The proportion of O-alkyl C was also significantly higher under the LM, HM and HML treatments, with increases of 5.5 %, 2.6 % and 2.2 %, respectively (P<0.05). In contrast, the proportions of aromatic C and carbonyl C were lower in the manure-amended treatments, with reduction of 12.4 %–13.2 % and 0.9 %–8.7 %, respectively (P<0.05).

Figure 1CPMAS-13C-NMR spectra under no manure (Control), low manure (LM), high manure (HM) and high manure plus lime (HML) treatments. Alkyl (0–45 ppm); O-alkyl C (45–110 ppm); aromatic C (110–160 ppm) and carbonyl C (160–220 ppm).

Table 3The contents of various C functional groups in CPMAS-13C-NMR spectra under no manure (Control), low manure (LM), high manure (HM) and high manure plus lime (HML) treatments. Alkyl (0–45 ppm); O-alkyl C (45–110 ppm); aromatic C (110–160 ppm) and carbonyl C (160–220 ppm).

Values are the means (n=3). Different lowercase letters after values in the same row indicate a significant difference among four manure treatments (P<0.05). Aromaticity = aromatic C (alkyl C + O-alkyl C + aromatic C); aliphatic C = (alkyl C + O-alkyl C); aliphaticity = (alkyl C + O-alkyl C) (alkyl C + O-alkyl C + aromatic C).

Relative to the Control, the alkyl C O-alkyl C ratio was significantly lower under the LM treatment (P<0.05), whereas the HM and HML treatments had no significant effect on the ratio (P>0.05, Table 3). The aromaticity was decreased by 14.4 %, 12.9 % and 13.2 % under LM, HM and HML treatments, respectively (P<0.05, Table 3). Similarly, the aromatic C O-alkyl C ratio was 14.7 %–17.7 % lower in the manured treatment (P<0.05, Table 3). Conversely, both the aliphatic C aromatic C ratio and aliphaticity were higher in the manured treatments, with elevations of 18.1 %–20.7 % and 2.44 %–3.66 %, respectively (P<0.05, Table 3).

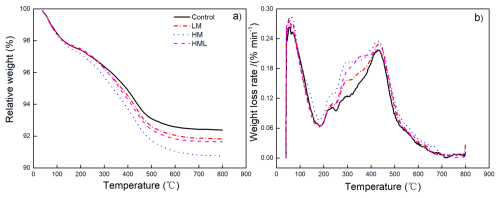

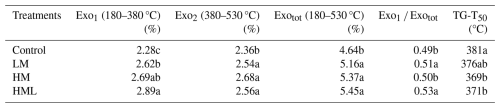

3.4 The effect of long-term pig manure application on SOC thermal stability

The shapes of TG and its first derivatives (DTG) curves showed distinct weight losses rate as temperature increased to above 100 °C, in the order of HM > HML > LM > Control (Fig. 2). Relative to the Control treatment, pig manure application significantly increased the total mass losses in the range of 180 to 530 °C (Exotot) by 11.1 %–17.4 % (P<0.05, Table 4), and significantly increased the mass losses during 180–380 °C (Exo1) and 380–530 °C (Exo2) by 14.6 %–26.5 % and 7.8 %–13.7 %, respectively (P<0.05, Table 4). The ratio of Exo1 Exotot was significantly elevated in the LM and HM treatments (P<0.05), whereas the HM treatment showed no significant effect relative to the Control (P>0.05, Table 4). HM and HML treatments significantly decreased TG-T50 by 10.7–12.0 °C (P<0.05), while LM treatments showed no significant difference compared to Control (P>0.05, Table 4).

Figure 2Thermogravimetry (TG) curves (a) and corresponding derivative thermogravimetry (DTG) curves (b) of soil organic matter (SOM) under no manure (Control), low manure (LM), high manure (HM) and high manure plus lime (HML) treatments.

Table 4The mass losses during specific temperature ranges under no manure (Control), low manure (LM), high manure (HM) and high manure plus lime (HML) treatments. Exo1 represents thermally labile soil organic matter (SOM); Exo2 represents thermally stable SOM; Exotot represents total SOM. TG-T50 indicates the temperature at which half of the total SOM is lost.

Values are the means (n=3). Different lowercase letters after values in the same row indicate a significant difference among four manure treatments (P<0.05).

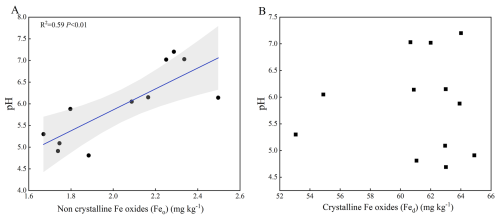

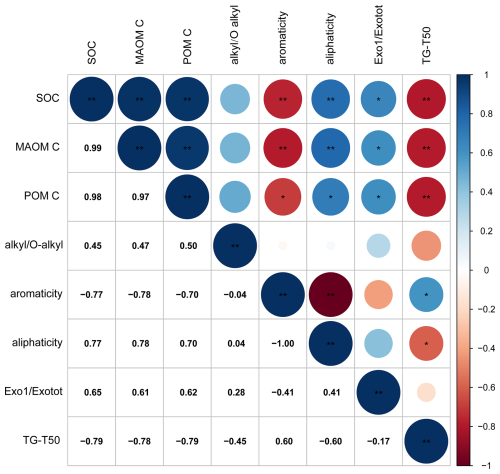

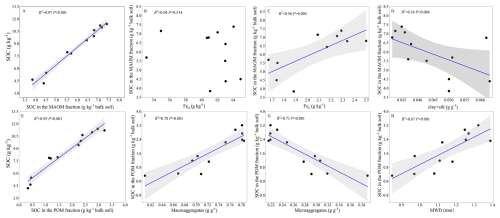

3.5 Relationships between SOC and factors related to the mineral protection and physical protection of SOC

Figure 3 showed correlations between SOC and possible variables associated with the chemical protection and physical protection of SOC. SOC in the bulk soil was significantly positively correlated with MAOM C (R2=0.97, Fig. 3A). MAOM C showed no relationship with Fed (R2=0.04, Fig. 3B), but it was positively correlated with Feo (R2=0.56, Fig. 3C). A weaker correlation was observed between MAOM C and the content of clay and silt (R2=0.34, P=0.46, Fig. 3D). Notably, Feo concentration was significantly and positively correlated with pH (R2=0.59, P<0.01; Fig. 4A). Conversely, the concentration of Fed was not correlated with pH (P>0.05; Fig. 4B).

Figure 3The relationships between SOC and variables related to the chemical protection and physical protection.

SOC in the bulk soil was significantly positively correlated with POM C (R2=0.95, Fig. 3E). POM C was significantly associated with soil aggregation, evidenced by the positive correlation with macroaggregates (>0.25 mm) (R2=0.78, Fig. 3F) and MWD (R2=0.67, Fig. 3H), whereas a negative correlation was observed with microaggregates (<0.25 mm) (, Fig. 3G).

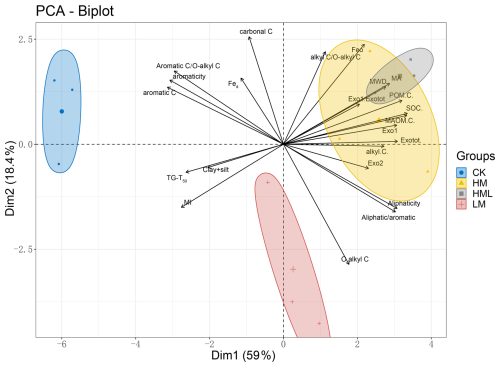

A PCA plot diagram (Fig. 5) revealed distinct associations between SOC quantity/quality and stabilization mechanisms. SOC vector aligned positively with POM C, macroaggregates and MWD, but inversely with microaggregates. Chemically, SOC covaried with MAOM C and Feo, yet formed an obtuse angle (>90°) with Fed. TG-T50 negatively associated with the proportion of O-alkyl C and aliphaticity (angles >90°), but positively linked to aromatic C and aromaticity (angles <90°).

Figure 5Biplots of the principal component analysis (PCA) between the quantity and quality of SOC and variables related to chemical protection, physical protection across four manure application treatments (CK, Control; LM, low manure; HM, high manure; and HML, high manure plus lime).

4.1 POM C and physical protection

Long-term pig manure application caused an increase of SOC in the bulk soil relative to the Control, and the increase was mainly derived from continuous manure inputs (Gong et al., 2009). Although maize rhizodeposition (including root exudates and sloughed-off cells) (typically <10 % of net primary productivity; Pausch and Kuzyakov, 2018) contributes to SOC during the growing season, its annual carbon inputs are only 0.2–0.5 Mg C ha−1 yr−1 (Dennis et al., 2010). This plant-derived C input is much lower than that from manure, which ranged from 1.6 to 6.4 Mg C ha−1 yr−1 in the LM and HM treatments, respectively. The rigorous removal of all harvest residues (stalks and recoverable roots) minimized aboveground and root biomass as a source of soil carbon deposition. It should be noted that some residual plant-derived materials (e.g., fine root fragments and exudates) have contributed marginally to the SOC pool. Given the relatively small quantity of plant-derived carbon inputs, the changes in SOC observed in this study are primarily attributable to the application of pig manure. Following microbial decomposition and transformation, the applied manure-C was progressively partitioned into distinct SOC pools.

Manure-derived carbon was preferentially allocated to the POM fraction rather than the MAOM fraction. The contribution of POM C to SOC in the manure-amended treatment was nearly threefold as that in the Control (8.8 % to 26.0 %), while the proportion of MAOM C decreased significantly from 82.4 % in the Control to 65.4 %–71.0 % in the manure application treatments (Table 2). The result was in line with Lan et al. (2022) and Li et al. (2018), who reported that increased manure substitution improved the POM C MAOM C ratio, indicating manure was beneficial to the formation of POM C.

These results implied carbon inputs are preferentially stabilized as POM rather than MAOM. This finding is supported by biomarker evidence showing a great contribution of plant-derived carbon to the POM fraction (Zou et al., 2023). Consistent with this, a 13C isotopic tracing study revealed that 70 %–87 % of residue-derived SOC was accumulated in the POM fraction at two experimental sites (Mitchell et al., 2021). The mechanism behind this preferential sequestration is the physical occlusion of fresh organic material within macroaggregates, which provides initial protection against rapid microbial decomposition. Therefore, POM C can be a good indicator of SOC dynamics under field management (Álvaro-Fuentes et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2023).

While POM C is inherently labile and susceptible to decomposition, it can be physically protected from rapid decay through occlusion within stable soil aggregates. According to the classical hierarchical aggregation model (Six et al., 2000), organic carbon acts as a primary binding agent for microaggregates (<0.25 mm) to form macroaggregates (>0.25 mm), with POM serving as both a structural nucleus and a transient carbon reservoir (Six et al., 2000). In this study, macroaggregates were significantly increased, and free microaggregates were significantly decreased after pig manure application (Table 1). These results implied that manure-derived carbon acted as binding agent, promoting the formation of macroaggregates from free microaggregates. This process provides physical protection for SOC, particularly that in the POM fraction, within the newly formed aggregates, particularly in the POM fraction (Peng et al., 2023). The observed positive correlation between POM C and both macroaggregates and aggregate MWD (Figs. 3, 4) further suggested the critical role of soil aggregation. However, the physical mechanisms by which POM facilitates this process (e.g., microbial mediation, hydrophobic interactions, or polysaccharide bridging) require further investigation. Experimental approaches such as isotopic labelling combined with micro-scale imaging (e.g., electron microscopy or X-ray computed tomography) can visualize the spatial distribution of POM within aggregates and quantify its role in aggregate formation. Future study should pay attention to these new technologies.

4.2 MAOM C and chemical protection

MAOM retained higher SOC concentrations (4.18–7.09 g C kg−1 bulk soil) than the POM fraction did, irrespective of treatments, though its contribution to total SOC decreased after manure application (Table 2). This underscores that organo-mineral complexation, rather than physical protection within aggregates, is the primary stabilization pathway in these red soils, even under significant organic input. MAOM C exhibited significantly longer mean residence time (MRT) compared to POM C, with reported turnover periods of 26–40 years versus 2.4–4.3 years, respectively (Benbi et al., 2014; Garten and Wullschleger, 2000). This fundamental difference originates from the unique stabilization mechanism of MAOM C through persistent organo-mineral associations (Lavallee et al., 2019). While clay minerals are widely recognized as key MAOM stabilizers (Hemingway et al., 2019; Liang et al., 2017), our study reveals a distinct iron oxide-dominated mechanism in these Fe-rich red soils. The strong correlation between MAOM C and non-crystalline Fe oxides (Feo, R2=0.56; Figs. 3C, 4) highlighted the pivotal role of Feo on SOC stabilization in this red soil. This iron-mediated stabilization likely stems from the exceptionally high specific surface area of Feo (∼ 800 m2 g−1 in ferrihydrite; Kleber et al., 2005) and its superior capacity to form stable organo-mineral complexes (Eusterhues et al., 2005; Lehmann and Kleber, 2015). Previous studies have demonstrated that organic amendments can enhance the content of non-crystalline Fe oxides, thereby promoting Fe-C associations (Chen et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019). Extending these findings, our results provide new mechanistic insight by demonstrating that the increase in non-crystalline Fe oxides is closely linked to manure-induced soil alkalization. Specifically, the significant positive correlation between pH and Fe0 indicates that the increased pH after manure application (Table 1) created conditions favoring Feo preservation (Vithana et al., 2015), with an increase of 25.4 % in the content of Feo. The higher Feo content provided abundant reactive surfaces for MAOM formation. The nature of this interaction likely involves specific molecular-scale binding mechanisms. Recent advances in synchrotron-based spectroscopy (e.g., STXM-NEXAFS) have provided direct evidence that poorly crystalline iron oxides (e.g., ferrihydrite) stabilize organic carbon primarily through ligand exchange, where carboxyl (-COOH) and hydroxyl (-C-OH) functional groups in organic molecules replace the surface hydroxyl groups on Fe oxides (Ruiz et al., 2024). Furthermore, coprecipitation, where organic matter is encapsulated within the matrix of forming Fe (oxyhydr) oxides, represents another potent stabilization mechanism that can generate long-term sinks for organic carbon (Chen and Sparks, 2015). While our bulk data cannot unequivocally distinguish between these mechanisms, the correlation suggests that similar processes are likely operative in our system, contributing to the stability of the large MAOM C pool. This pH-Feo-MAOM nexus establishes a self-reinforcing stabilization mechanism: manure-derived organic ligands interact with Feo to form stable complexes, simultaneously protecting both organic carbon and Feo from dissolution (Kleber et al., 2021).

The positive correlation between Feo and MAOM C (Fig. 3C) suggested that non-crystalline Fe oxides played a critical role in stabilizing SOC through organo-mineral interactions. However, while our data support the association between Feo and MAOM C, the underlying mechanisms (e.g., adsorption, co-precipitation, or ligand exchange) remain speculative due to the lack of direct molecular-scale evidence. Future studies employing advanced spectroscopic techniques (e.g., synchrotron-based X-ray absorption spectroscopy or Nano-SIMS) could explicitly characterize the binding forms of Fe-organic complexes, thereby validating the causal relationship between Feo and MAOM formation.

4.3 Chemical composition and thermal stability

Input of new organic material could alter chemical composition of SOC and lead to the change of the molecule recalcitrance of SOC (Guo et al., 2019; Yan et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2013). In the current study, pig manure application resulted in a higher proportion of O-alkyl C but a lower proportion of aromatic C. Given pig manure was rich in cellulose and lignin components, its introduction substantially increased O-alkyl C relative to the Control (Li et al., 2015). The considerable accumulation of O-alkyl C accounted for the reduction of the relative proportion of aromatic C and the lower aromaticity.

Long-term pig manure application strengthened SOC thermal stability by improving the content of thermally stable organic matters while it decreased TG-T50. The observed increase in the absolute amount of thermally stable SOC (Exo2) can be attributed to the formation of stable organo-mineral complexes with newly formed Feo. As elucidated by Kleber et al. (2021), the thermal stability of organic matter is significantly enhanced upon binding to mineral surfaces. Thermal analysis suggested that manure amend significantly increased SOM content, evidenced by the increase of the mass losses during 180–530 °C (Exotot) (Table 4). The result was consistent with the change of SOC content measured by conventional method (Table 1), indicating TG technology was promising for measuring SOM content (Siewert, 2004; Tokarski et al., 2018). The decrease of TG-T50 reflected more easily decomposable SOC accumulated after manure application (Gao et al., 2015; Siewert, 2004). The result consisted with that in the NMR spectroscopy, where greater O-alkyl C and higher aliphaticity were found under manure treatments (Table 3). SOC with more O-alkyl C functional groups or higher aliphaticity was less likely to resist thermochemical degradation as revealed by the negative relationship between TG-T50 and aliphacity (Figs. 5, 6) (Hou et al., 2019; Lehmann and Kleber, 2015), thus leading to a decrease of TG-T50. In this study, the thermally labile organic matters accounted for over half of the total organic matters, so the decrease of TG-T50 after manure application was just a result of the increased thermally organic matters not the decrease of thermal stability. In contrast, thermal stability should be strengthened according to the increased thermally stable organic matters after manure application. The observed decrease TG-T50 and the simultaneous increase in Exo2 are not contradictory. This apparent paradox can be explained by the dual effect of manure amendment: the input of a large quantity of labile, manure-derived organic compounds significantly increased the proportion of thermally labile C, thereby reducing the average stability of the entire SOM pool (as reflected by the decreased TG-T50). Concurrently, the manure-induced biogeochemical changes (e.g., increased pH and Fe oxide transformation) promoted the formation of highly stable organo-mineral complexes. While the relative proportion of this stable C might be diluted by the new labile C, its absolute amount within the soil system increased substantially, which is captured by the increase in the absolute Exo2 signal. Since soil structure was destroyed due to the ground process of soil samples before TG analysis, the increase of the thermally stable organic matters was ascribed to mineral protection, where the correlations between organic carbon and Fe oxides increased the thermally resistance of OC (Ruiz et al., 2023).

Manure application increased SOC quantity and improved its quality in Fe-rich red soils. SOC in the POM fraction exhibited the most pronounced response to manure inputs, while the majority of SOC was stored in the MAOM fraction. Furthermore, SOC was stabilized by distinct yet complementary mechanisms: physical protection via aggregation process, and chemical protection via Fe-organic associations induced by elevated pH. In addition, manure application increased thermally stable organic matters. However, to better understand inherent mechanisms, future work should focus on molecular-scale characterization of Fe-organic interactions using synchrotron techniques (e.g., Fe K-edge XANES/EXAFS), and in-situ visualization of POM-mediated aggregation through advanced imaging tools (e.g., SEM-TEM or μ-CT) coupled with 13C-labelled manure to track POM dynamics within aggregates.

The code and data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-11-1095-2025-supplement.

HR conceived the experimental approach, took soil samples from the field, carried out the laboratory and data analyses, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and contributed to subsequent drafts. ZLD helped analyze NMR spectrum and revise the manuscript. WDG contributed to interpretating TG data and revising the manuscript. LXM conducted the experiment of NMR. XHP helped design the experiment, and analyze data. YJJ contributed to the design of field experiment and the process of taking soil samples. DMY contributed to the process of writing. HZ contributed to funding acquisition, conceiving the experimental approach, carrying out data interpretations, and the writing of all subsequent manuscript drafts.

At least one of the (co-)authors is a member of the editorial board of SOIL. The peer-review process was guided by an independent editor, and the authors also have no other competing interests to declare.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We thank Yanyan Cai and Xing Xia for laboratory assistance.

This work was financially supported by the NSFC-CAS Joint Fund Utilizing Large-scale Scientific Facilities (No. U1832188) and Chinese Universities Scientific Fund (2023RC047).

This paper was edited by Jocelyn Lavallee and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Álvaro-Fuentes, J., Franco-Luesma, S., Lafuente, V., Sen, P., Usón, A., Cantero-Martínez, C., and Arrúe, J. L.: Stover management modifies soil organic carbon dynamics in the short-term under semiarid continuous maize, Soil Till. Res., 213, 105143, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2021.105143, 2021.

Amelung, W., Bossio, D., de Vries, W., Kögel-Knabner, I., Lehmann, J., Amundson, R., Bol, R., Collins, C., Lal, R., Leifeld, J., Minasny, B., Pan, G., Paustian, K., Rumpel, C., Sanderman, J., van Groenigen, J. W., Mooney, S., van Wesemael, B., Wander, M., and Chabbi, A.: Towards a global-scale soil climate mitigation strategy, Nat. Commun., 11, 5427, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18887-7, 2020.

Bai, X. X., Tang, J., Wang, W., Ma, J. M., Shi, J., and Ren, W.: Organic amendment effects on cropland soil organic carbon and its implications: A global synthesis, Catena, 231, 107343, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2023.107343, 2023.

Baldock, J. A., Oades, J. M., Nelson, P. N., Skene, T. M., Golchin, A., and Clarke, P.: Assessing the extent of decomposition of natural organic materials using solid-state 13C NMR spectroscopy, Soil Res., 35, 1061–1084, https://doi.org/10.1071/S97004, 1997.

Benbi, D. K., Boparai, A. K., and Brar, K.: Decomposition of particulate organic matter is more sensitive to temperature than the mineral associated organic matter, Soil Biol. Biochem., 70, 183–192, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.12.032, 2014.

Cambardella, C. A. and Elliott, E. J.: Particulate soil organic-matter changes across a grassland cultivation sequence, Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J., 5, 777–783, https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1992.03615995005600030017x, 1992.

Chen, C. M. and Sparks, D. L.: Multi-elemental scanning transmission X-ray microscopy-near edge X-ray absorption fine structure spectroscopy assessment of organo-mineral associations in soils from reduced environments, Environ. Chem., 12, 64–73, https://doi.org/10.1071/EN14042, 2015.

Chen, M., Zhang, S., and Liu, L.: Organic fertilization increased soil organic carbon stability and sequestration by improving aggregate stability and iron oxide transformation in saline-alkaline soil, Plant Soil, 474, 233–249, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-022-05326-3, 2022.

Chenu, C., Angers, D. A., Barre, P., Derrien, D., Arrouays, D., and Balesdent, J.: Increasing organic stocks in agricultural soils: Knowledge gaps and potential innovations, Soil Till. Res., 188, 41–52, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2018.04.011, 2019.

Cotrufo, M. F., Ranalli, M. G., Haddix, M. L., Six, J., and Lugato, E.: Soil carbon storage informed by particulate and mineral-associated organic matter, Nature Geosci., 12, 989–996, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-019-0484-6, 2019.

Dennis, P. G., Miller, A. J., and Hirsch, P. R.: Are root exudates more important than other sources of rhizodeposits in structuring rhizosphere bacterial communities?, FEMS Microbiol. Ecol., 72, 313–327, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.00860.x, 2010.

Du, Z. L., Han, X., and Guo, L. P.: Changes in soil organic carbon concentration, chemical composition and aggregate stability as influenced by tillage systems in the semi-arid and semi-humid area of North China, Can. J. Soil Sci., 98, 91–102, https://doi.org/10.1139/cjss-2017-0045, 2017.

Eusterhues, K., Rumpel, C., and Kögel-Knabner, I.: Organo-mineral association in sandy acid forest soils: importance of specific surface area, iron oxides and micropores, Eur. J. Soil Sci., 56, 753–763, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2389.2005.00710.x, 2005.

Gao, Q. Q., Ma, L. X., Fang, Y. Y., Zhang, A. P., Li, G. C., Wang, J. J., Wu, D., Wu, W. L., and Du, Z. L.: Conservation tillage for 17 years alters the molecular composition of organic matter in soil profile, Sci. Total Environ., 762, 143116, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143116, 2021.

Gao, W. D., Zhou, T. Z., and Ren, T. S.: Conversion from conventional to no tillage alters thermal stability of orga-nic matter in soil aggregates, Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J., 79, 585–594, https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2014.08.0334. 2015.

Garten, C. T. and Wullschleger, S. D.: Soil carbon dynamics beneath switchgrass as indicated by stable isotope analysis, J. Environ. Qual., 29, 645–653, https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2000.00472425002900020036x, 2000.

Gong, W., Yan, X. Y., Wang, J. Y., Hu, T. X., and Gong, Y. B.: Long-term manure and fertilizer effects on soil organic matter fractions and microbes under a wheat–maize cropping system in northern China, Geoderma, 149, 318–324, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2008.12.010, 2009.

Guo, Z. C., Zhang, J. B, Fan, J., Yang, X. Y., Yi, Y. L., Han, X. R., Wang, D. Z., Zhu, P., and Peng, X. H.: Does animal manure application improve soil aggregation? Insights from nine long-term fertilization experiments, Sci. Total Environ., 660, 1029–1037, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.01.051, 2019.

Hemingway, J. D., Rothman, D. H., Grant, K. E., Rosengard, S. Z., Eglinton, T. I., Derry, L. A., and Galy, V.: Mineral protection regulates long-term preservation of natural organic carbon, Nature, 570, 2717–2726, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1280-6, 2019.

Hou, Y. H., Chen, Y., Chen, X., He, K., and Zhu, B.: Changes in soil organic matter stability with depth in two alp-ine ecosystems on the Tibetan Plateau, Geoderma, 351, 153–162, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2019.05.034, 2019.

Huang, X., Feng, C., and Zhao, G.: Carbon Sequestration Potential Promoted by Oxalate Extractable Iron Oxides through Organic Fertilization, Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J., 81, 1359–1370, https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2017.02.0068, 2017.

Jiang, Y. J., Zhou, H., Chen, L. J., Yuan, Y., Fang, H., Luan, L., Chen, Y., Wang, X. Y., Liu, M., Li, H. X., Peng, X. H., and Sun, B.: Nematodes and microorganisms interactively stimulate soil organic carbon turnover in the macroaggregates, Front Microbiol., 9, 2803, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.02803, 2018.

Kleber, M., Mikutta, R., Torn, M. S., and Jahn, R.: Poorly crystalline mineral phases protect organic matter in acid subsoil horizons, Eur. J. Soil Sci., 717–725, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2389.2005.00706.x, 2005.

Kleber, M., Bourg, I. C., Coward, E. K., Hamsel, C. M., Myneni, S. C. B., and Nunan, N.: Dynamic interactions at the mineral-organic matter interface, Nat. Rev. Earth Environ., 2, 402–421, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-021-00162-y, 2021.

Kögel-Knabner, I.: 13C and 15N NMR spectroscopy as a tool in soil organic matter studies, Geoderma, 80, 243–270, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7061(97)00055-4, 1997.

Lal, R.: Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security, Science, 304, 1623–1627, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1097396, 2004.

Lan, Z. J., Shan, J., Huang, Y., Liu, X. M., Lv, Z. Z., Ji, J. H., Hou, H. Q., Xia, W. J., and Liu, Y. R.: Effects of long-term manure substitution regimes on soil organic carbon composition in a red paddy soil of southern China, Soil Till. Res., 221, 105395, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2022.105395, 2022.

Lavallee, J. M., Soong, J. L., and Cotrufo, M. F.: Conceptualizing soil organic matter into particulate and mineral-associated forms to address global change in the 21st century, Glob. Chang Biol., 26, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14859, 2019.

Le Bissonnais, Y.: Aggregate stability and assessment of soil crustability and erodibility: I. Theory and methodology, Eur. J. Soil Sci., 47, 425–437, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2389.1996.tb01843.x, 1996.

Lehmann, J. and Kleber, M.: The contentious nature of soil organic matter, Nature, 528, 60–68, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16069, 2015.

Li, J., Wen, Y., Li, X., Li, Y., Yang, X., Lin, Z., Song, Z., Cooper, J., and Zhao, B.: Soil labile organic carbon fractions and soil organic carbon stocks as affected by longterm organic and mineral fertilization regimes in the North China Plain, Soil Till. Res., 175, 281–290, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2017.08.008, 2018.

Li, Z. Q., Zhao, B. Z., Wang, Q., Cao, X. Y., and Zhang, J. B.: Differences in chemical composition of soil organic carbon resulting from long-term fertilization strategies, PLoS One, 10, e0124359, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0124359, 2015.

Lian, T. X., Wang, G. H., Yu, Z. H., Li, Y. S., Liu, X. B., and Jin, J.: Carbon input from 13C-labelled soybean residues in particulate organic carbon fractions in a Mollisol, Biol. Fertil. Soils, 52, 331–339, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-015-1080-6, 2015.

Liang, C., Schimel, J. P., and Jastrow, J. D.: The importance of anabolism in microbial control over soil carbon storage, Nat. Microbiol., 2, 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.105, 2017.

Liu, S. B., Wang, J. Y., Pu, S. Y., Blagodatskaya, E., Kuzyakov, Y., and Razavi, B. S.: Impact of manure on soil biochemical properties: A global synthesis, Sci. Total Environ., 745, 141003, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141003, 2020.

Mitchell, E., Scheer, C., Rowlings, D., Contrufo, F., Conant, R. T., and Grace, P.: Important constraints on soil organic carbon formation efficiency in subtropical and tropical grasslands, Glob. Change Bio., 27, 5383–5391, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15807, 2021.

Mustafa, A., Xu, H., Shah, S. A. A., Abrar, M. M., Maitlo, A. A., Kubar, K. A., Saeed, Q., Kamran, M., Naveed, M., Wang, B. R., Sun, N., and Xu, M. G.: Long-term fertilization alters chemical composition and stability of aggregate-associated organic carbon in a Chinese red soil: evidence from aggregate fraction, C mineration, and 13C NMR analyses, J. Soil Sediment., 21, 2483–2496, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-021-02944-9, 2021.

Nichitha, C. V., Raghaven, S., Champa, B. V., Ganapathi, G., Sudarshan, V., Nandita, S., Ravikumar, D., and Nagaraja, M. S.: Role of organic manures on soil carbon stocks and soil enzyme activities in intensively managemend ginger production systems, Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric., 1579, https://doi.org/10.30486/IJROWA.2023.1977064.1579, 2023.

Pausch, J. and Kuzyakov, Y.: Carbon input by roots into the soil: Quantification of rhizodeposition from root to ecosystem cell, Global Change Biol., 24, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13850, 2018.

Peng, X. Y., Huang, Y., Duan, X. W., Yang, H., and Liu, J. X.: Particulate and mineral-associated organic carbon fractions reveal the roles of soil aggregates under different land-use types in a karst faulted basin of China, Catena, 220, 106721, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2022.106721, 2023.

Poeplau, C., Don, A., Six, J., Kaiser, M., Benbi, D., Chenu, C., Cotrufo, M. F., Derrien, D., Gioacchini, P., Grand, S., Gregorich, E., Griepentrog, M., Gunina, A., Haddix, M., Kuzyakov, Y., Kühnel, A., Macdonald, L. M., Soong, J., Trigalet, S., Vermeire, M.-L., Rovira, P., van Wesemael, B., Wiesmeier, M., Yeasmin, S., Yevdokimov, I., and Nieder, R.: Isolating organic carbon fractions with varying turnover rates in temperate agricultural soils – A comprehensive method comparison, Soil Biol. Biochem., 125, 10–26, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.06.025, 2018.

Ruiz, F., Rumpel, C., Dignac, M.-F., Baudin, F., and Ferreira, T. O.: Combing thermal analyses and wet-chemical extractions to assess the stability of mixed-nature soil orgnaic matter, Soil Biol. Biochem., 187, 109216, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2023.109216, 2023.

Ruiz, F., Bernardino, A. F., Queiroz, H. M., Otero, X. L., Rumpel, C., and Ferreira, T. O.: Iron's role in soil organic carbon (de)stabilization in mangroves under land use change, Nat. Commun., 10433, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54447-z, 2024.

Siewert, C.: Rapid screening of soil properties using thermogravimetry, Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 68, 1656–1661, https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2004.1656, 2004.

Simpson, M. J. and Simpson, A. J.: The chemical ecology of soil organic matter molecular constituents, J. Chem. Ecol., 38, 768–784, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-012-0122-x, 2012.

Six, J., Elliot, E. T., and Paustian, K.: Soil macroaggregate turnover and microaggregate formation: a mechanism for C sequestratioin under no-tillage agriculture, Soil Biol. Biochem., 32, 2099–2103, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0038-0717(00)00179-6, 2000.

Six, J., Conant, R. T., Paul, E. A., and Paustian, K.: Stabilization mechanisms of soil organic matter: Implications for C-saturated of soils, Plant Soil, 241, 155–176, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016125726789, 2002.

Soil Survey Staff: Soil survey laboratory information manual. Soil survey investigations report No. 45, version 2.0, edited by: Burt, R., U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/sites/default/files/2022-10/SSIR45.pdf (last access: 15 May 2025), 2011.

Song, X. X., Wang, P., van Z, L., Bolan, N., Wang, H. L., Li, X. M., Cheng, K., Yang, Y., Wang, M., Liu, T. X., and Li, F. B.: Towards a better understanding of the role of Fe cycling in soil for carbon stabilization and degradation, Carbon Research, 1, 5, https://doi.org/10.1007/s44246-022-00008-2, 2022.

Tokarski, D., Kučerík, J., Kalbitz, K., Demyan, M. S., Merbach, I., Barkusky, D., Ruehlmann, J., and Siewert, C.: Contribution of organic amendments to soil organic matter detected by thermogravimetry, J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci., 181, 664–674, https://doi.org/10.1002/jpln.201700537, 2018.

Vithana, C. L., Sullivan, L. A., Burton, E. D., and Bush, R. T.: Stability of schwertmannite and jarosite in an acidic landscape: Prolonged field incubation, Geoderma, 239–240, 47–57, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2014.09.022, 2015.

Volkov, D. S., Rogova, O. B., Proskurnin, M. A., Farkhodov, Y. R., and Markeeva, L. B.: Thermal stability of organic matter of typical chernozems under different land uses, Soil Till. Res., 197, 104500, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2019.104500, 2020.

Wang, S. B., Hu, K. L., Feng, P. Y., Wei, Q., and Leghari, S. J.: Determining the effects of organic manure substitution on soil pH in Chinese vegetable fields: a meta-analysis, J. Soil. Sediment, 23, 118–130, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-022-03330-9, 2023.

Wang, P., Wang, J., and Zhang, H.: The role of iron oxides in the preservation of soil organic matter under long-term fertilization, J. Soils Sediments, 19, 588–598, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-018-2085-1, 2019.

Wu, J. J., Zhang, H., Pan, Y. T., Cheng, X. L., Zhang, K. R., and Liu G. H.: Particulate organic carbon is more sensitive to nitrogen addition than mineral-associated organic carbon: A meta-analysis, Soil Till. Res., 232, 105770, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2023.105770, 2023.

Yan, X., Zhou, H., Zhu, Q. H., Wang, X. F., Zhang, Y. Z., Yu, X. C., and Peng, X. H.: Carbon sequestration efficiency in paddy soil and upland soil under long-term fertilization in southern China, Soil Till. Res., 130, 42–51, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2013.01.013, 2013.

Zhang, B. Y., Dou, S., Guo, D., and Guan, S.: Straw inputs improve soil hydrophobicity and enhance organic carbon mineralization, Agronomy, 13, 2618, https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13102618, 2023.

Zhang, J. C., Zhang, L., Wang, P., Huang, Q. W., Yu, G. H., Li, D. C., Shen, Q. R., and Ran, W.: The role of non-crystalline Fe in the increase of SOC after long-term organic manure application to the red soil of southern China, Eur. J. Soil Sci., 64, 797–804, https://doi.org/10.1111/ejss.12104, 2013.

Zhou, H., Fang H., Zhang, Q., Wang, Q., Chen, C., Mooney, S. J., Peng, X. H., and Du, Z. L.: Biochar enhances soil hydraulic function but not soil aggregation in a sandy loam, Eur. J. Soil Sci., 70, 291–300, https://doi.org/10.1111/ejss.12732, 2019.

Zhou, P., Pan, G. X., Spaccini, R., and Piccolo, A.: Molecular changes in particulate organic matter (POM) in a typical Chinese paddy soil under different long-term fertilizer treatments, Eur. J. Soil Sci., 61, 231–242, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2389.2009.01223.x, 2010.

Zou, Z. C., Ma, L. X., Wang, X., Chen, R. R., Jones, D. L., Bol, R., Wu, D., and Du, Z. L.: Decadal application of mineral fertilizers alters the molecular composition and origins of organic matter in particulate and mineral-associated fractions, Soil Biol. Biochem., 182, 109042, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2023.109042, 2023.