the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Warming accelerates the decomposition of root-derived hydrolysable lipids in a temperate forest and is depth- and compound class-dependent

Cyrill Zosso

Guido L. B. Wiesenberg

Elaine Pegoraro

Margaret S. Torn

Michael W. I. Schmidt

Global warming could potentially increase the decomposition rate of soil organic matter (SOM), not only in the topsoil (<20 cm) but also in the subsoil (>20 cm). Despite its low carbon content, subsoil holds on average nearly as much SOM as topsoil across various ecosystems. However, significant uncertainties remain regarding the impact of warming on SOM decomposition in subsoil, particularly root-derived carbon, which serves as the primary organic input at these horizons. In a whole-soil field warming experiment at Blodgett Forest Research Station (California, USA), we investigated whether warming accelerates the decomposition of root-derived hydrolysable lipids in the top- (10–14 cm) and subsoil (45–49, 85–89 cm) by using molecular markers and in-situ incubation of 13C-labeled root litter at each depth. Our results reveal that at compound-class level, hydrolysable lipids presented compound-dependent responses. Warming consistently reduced fatty acid mass change across soil depths, particularly at 85–89 cm. In subsoil, there was accumulation of fatty acids, which primarily originated from microbial-derived mid-chain fatty acids such as octadecanoic acid (C18:0 fatty acids), octadecenoic acid (C18:1 fatty acids), and hexadecanoic acid (C16:0 fatty acids). Higher temperature attenuated this accumulation, indicating less microbial transformation of root-derived carbon under warming. At monomer level, ω-hydroxy acids and diacids as suberin markers were more resistant to decomposition than bulk root-derived carbon and their resistance increased with chain-length. Moreover, warming accelerated decomposition of individual suberin monomers in the topsoil but suppressed it in the subsoil. The slower decomposition in the subsoil was likely due to lower microbial abundance and lower soil moisture induced by warming. Our study demonstrates that the impact of warming on the decomposition of root-derived hydrolysable lipids in a temperate forest is compound class- and depth-dependent. The persistence of long-chain ω-hydroxy acids and diacids may provide a potential way for long-term carbon stabilization in subsoil under climate change. Nevertheless, due to the substantial heterogeneity of subsoil environment, further studies are required to confirm and generalize this finding.

- Article

(1034 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(865 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

-

Warming effect on decomposition of root-derived hydrolysable lipids was compound class-dependent

-

Warming attenuated the accumulation of fatty acids in the subsoil

-

Suberin markers are more resistant to decomposition and their resistance increased with chain-length

-

Warming accelerated decomposition of suberin-derived monomers but inhibited it in the subsoil

-

No priming effects on the pre-existing bulk soil carbon and hydrolysable lipids after 3 years.

Global air temperatures are projected to increase between 2.6 and 4.8 °C by 2100 under Representative Concentration Pathway 8.5, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2013). In synchrony with air temperature, soil temperature is also expected to increase, not only in topsoil (<20 cm) but also in subsoil (>20 cm) (Soong et al., 2020). Global soils hold the largest actively cycling terrestrial carbon pool and store between 2000 and 3000 Pg of carbon in the top 3 m, with over 50 % located in subsoil (Scharlemann et al., 2014). Previous studies demonstrated that warming could accelerate the decomposition of soil organic matter (SOM) in topsoil (Scharlemann et al., 2014), as well as in subsoil (Hicks Pries et al., 2017; Soong et al., 2021), potentially causing loss of CO2 to the atmosphere. Moreover, enhanced temperature accelerated the decomposition of complex polymeric organic matter (Ofiti et al., 2023; Zosso et al., 2023), which had been regarded as comparatively recalcitrant to microbial decomposition.

Often, manipulative field warming experiments have focused on topsoil (Chen et al., 2022; van Gestel et al., 2018; Melillo et al., 2017; Verbrigghe et al., 2022), both in terms of the soil depths warmed by the manipulation and focus of the investigation. Therefore, it remains unclear from these experiments if the deeper soil horizons respond in similar ways to environmental changes as topsoil, since biotic and abiotic properties differ. Subsoil SOM has been assumed to be relatively insensitive to warming, because larger proportions of this deep SOM are more spatially inaccessible to microorganisms due to their associations to mineral surfaces compared to surface soil (Lützow et al., 2006). Furthermore, the microbial abundance varies throughout the soil profile (Rumpel et al., 2012; Zosso et al., 2021). Microbial biomass is substantially higher in topsoil than in subsoil (Naylor et al., 2022), by as much as two orders of magnitude (Fierer et al., 2003), leading to significantly slower turnover of carbon in the subsoil (Spohn et al., 2016). Also, microbial community structure changes with depth. Across different ecosystems, there is generally a proportional increase of Gram-positive to Gram-negative bacteria with depth (Eilers et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2021; Zosso et al., 2021) due to decreased carbon availability and quality (Fanin et al., 2019; Naylor et al., 2022). With warming, the difference in microbial abundance and composition between topsoil and subsoil could become more pronounced (Fontaine et al., 2007; Zosso et al., 2021), leaving large uncertainties of the impact on SOM decomposition at different depths.

One of the most important biotic factors that could change the SOM dynamics in the subsoil is root mass. Compared to topsoil, root mass is one of the major carbon sources in the subsoil (Button et al., 2022; Rumpel and Kögel-Knabner, 2011), especially in seasonally dried temperate evergreen forest, where root depth could be deep (Schenk and Jackson, 2005). The dual role of roots can affect SOM dynamics in subsoil in contrasting ways. On one hand, root-derived carbon is more likely than aboveground plant biomass to associate with minerals (Jackson et al., 2017; Rasse et al., 2005; Sokol and Bradford, 2019), thus promote carbon stabilization. On the other hand, they can also stimulate microbial mineralization of previously stabilized SOM, leading to loss of old SOM in the subsoil (Dijkstra et al., 2021; Fontaine et al., 2007). However, it remains uncertain how root biomass and its microbial decomposition will respond to warming, particularly in subsoil. Previous studies showed a variety of responses of root biomass in the surface soil to warming, with either more fine root biomass (Kwatcho Kengdo et al., 2022; Malhotra et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021), less root biomass (Arndal et al., 2018; Ofiti et al., 2021), or no change in root biomass (Wang et al., 2017). In subsoil, it is assumed that roots will forage in deeper soil horizons under water stress induced by warming, (Wang et al., 2017, 2021) but the opposite was observed in a warming experiment in a temperate forest at Blodgett forest with a substantial loss of fine (<2 mm) and coarse roots (2–5 mm; Ofiti et al., 2021) across the soil profile after 4 years of warming. Additionally, it was also observed that warming (Parts et al., 2019; Yaffar et al., 2021) or higher temperature induced drought (Meier and Leuschner, 2008) increased mortality of fine root biomass. Since this root litter could serve as new substrates for carbon-limited subsoil horizons and fuel decomposition of pre-existing carbon, it is important to understand how microorganisms will respond to this new input at different depths under warming conditions.

Although previous studies have provided evidence of carbon loss under warming at Blodgett Forest (Soong et al., 2021), mainly by rapid decomposition of decadal-aged carbon (Hicks Pries et al., 2017), they have not addressed the transformation of new carbon inputs into SOM formation at the molecular level. Molecular proxies or markers such as plant-derived hydrolysable lipids suberin, which mainly derive from woody tissues such as roots (Kolattukudy, 1980), could be used as quantitative and qualitative methods to follow alterations of root-derived carbon during decomposition and determine their turnover rate when in combination with compound-specific 13C isotopic analysis (Feng et al., 2010). Moreover, it is important to know whether these molecular proxies could be preserved under warming. Because applying genetic modifications to improve plant traits associated with carbon sequestration (defined as “harnessing roots”), specifically to increase their hydrolysable lipids content, is regarded as one of the solutions to mitigate climate change (Eckardt et al., 2023).

Many previous studies on the mechanisms of the interaction between root-derived carbon and soil (decoupling carbon from mineral protection or formation of soil carbon) were conducted as laboratory incubation experiments (Keiluweit et al., 2015; Sokol and Bradford, 2019). Such techniques with high replicability and controlled conditions contribute to understanding certain soil carbon transformation or stabilization processes. However, laboratory incubations are usually far from natural conditions and lack many of the biotic or abiotic interactions that occur in soil in-situ.

Therefore, in our study, we used a long-term, whole-soil warming experiment, located at Blodgett Forest Research Station (CA, USA), to study the effect of warming on the decomposition of root litter at different soil depths (10–14, 45–49, and 85–89 cm). We incubated 13C-labeled roots in-situ for 3 years, to understand how the decomposition of root-derived hydrolysable lipids varies with depth and warming. Specifically, we quantified different monomers in hydrolysable lipids that were released from polymeric SOM. For each monomer we investigated stable carbon isotope values (δ13C) to understand how quickly root-derived carbon and molecular markers degraded at different soil depths with warming. We hypothesized that: first, warming would accelerate the decomposition of root-derived hydrolysable lipids throughout the entire soil profile, regardless of soil depths. Second, hydrolysable lipids would accumulate relative to bulk root-derived carbon due to their greater chemical persistence compared to other carbon compounds (Lorenz et al., 2007).

2.1 Study site

The whole-soil warming experiment at University of California Blodgett Experimental Forest is located on the foothills of the Sierra Nevada near Georgetown, CA (120°39′40′′ W; 38°54′43′′ N) at 1370 m a.s.l. (above sea level) (Hicks Pries et al., 2018). The site has a Mediterranean climate with a mean annual air temperature of 12.5 °C and a mean annual precipitation of 1774 mm (Bird and Torn, 2006). The experiment is situated in a thinned 80-year-old mixed coniferous temperate forest, dominated by ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa), sugar pine (Pinus lambertiana), incense cedar (Calodefrus decurrens), white fir (Abies concolor), and douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii; Hicks Pries et al., 2017). The soils are Holland series and classified as fine-loamy, mixed superactive, mesic ultic Alfisol of granitic origin (mean pH 5.5), which is equivalent to Dystric Cambisols (IUSS Working Group WRB, 2022).

Briefly, the whole-soil warming experiment consists of 6 plots in total arranged in three replicated blocks, each having a pair of warmed and controlled circular plots 3 m in diameter. To maintain warming down to 1 m depth, twenty-two 2.4 m-long resistance heating cables (BriskHeat, Ohio, USA) were vertically installed in metal conduits at a radius of 1.75 m, surrounding each plot. Two concentric rings of surface heater cable were installed at 1 and 2 m in diameter, 5 cm below the soil surface, to compensate for surface heat loss. The average soil temperature was elevated by +4 °C in warmed plots relative to ambient plots (except for at 0–20 cm only elevated by +2.6 °C due to surface heat loss), while preserving seasonality and natural temperature gradient with soil depth (Hicks Pries et al., 2017; Pegoraro et al., 2024). The setup of the control plots is identical to the warmed plots but without heating cables placed inside the metal conduits (Hicks Pries et al., 2017).

2.2 13C-labeled root litter experiment and sampling

Common wild oat (Avena fatua) is an annual grass whose fast growth enabled uniform 13C-labelling in this experiment compared in contrast to the slower-growing native coniferous trees. This made its roots a suitable model substrate for decomposition studies (Hicks Pries et al., 2018). Avena fatua seedlings were grown for 12 weeks in a greenhouse within an airtight chamber at the University of California, Berkeley. Every 4 d the source of CO2 was switched between ambient CO2 and 10 atom % 13CO2 (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc., Massachusetts, USA). After this labeling phase, roots were excavated, dried and cut in 1–2 cm pieces (<2 mm diameter). The root substrate was enriched by 5.6 % atom % 13C and had a carbon concentration of 0.463 g C g root−1 (Castanha et al., 2018; Hicks Pries et al., 2018).

A total of six soil cores were extracted in each plot by using a perforated custom coring system made of polycarbonate tube (5.04 cm outer diameter and 4.41 cm inner diameter). Each tube consisted of four sections (10, 35, 40, and 10 cm in length, respectively) that were threaded on each end (male threads) and connected with female-to-female threaded polycarbonate connectors. Each section was threaded onto a sharpened aluminum cutting edge at the bottom for coring, and an aluminum tube with a weighted pounding head on the top. We cored the mineral soil based on the length of each polycarbonate section at the following depths: 0–10, 10–45, 45–85, and 85–95 cm. The top 4 cm of soil in each section (target experiment depth: 10–14, 45–49, and 85–89 cm) was marked and scooped into aluminum tins. Then a pre-weighed, 0.14 g aliquot of Avena fatua fine roots were added. The labeled Avena root litter was added to four out of the six cores and these cores will be termed as root litter treatment in this paper. The same disturbance was applied to the rest of the two cores without addition of labeled root litter and will be denoted as disturbance control treatment. Mesh disks with 1 mm aperture were positioned at the top and bottom of each target 4 cm soil increment to delineate the physical boundaries of the inserted root substrates. This setup was intended to retain the added root litter and prevent ingrowth of living roots into the cores and was also done in disturbance control treatment. The soil mixture was then added back to each polycarbonate section. The polycarbonate core sections were consequently connected with the female-to-female connectors and the resulting 95 cm long core was placed back in the soil. In July 2019, i.e., after 3 years of in-situ field incubation, two cores with root litter treatment and one core with disturbance control treatment were retrieved from each plot. The retrieved cores were wrapped in foil and transported to Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and stored in a −20 °C freezer before further processing. The more detailed description of experimental setup and incubation methods is demonstrated in Pegoraro et al. (2024). For brevity, DC will be used to refer to the disturbance control treatment in the rest of this paper.

Because prior work at this site concentrated on three depths (Hicks Pries et al., 2017; Soong et al., 2021), we selected the same depths to facilitate cross-study, temporal and spatial comparisons. These depths also capture major pedogenic zones: topsoil, a transitional mid-depth between topsoil and subsoil, and the deep subsoil horizon.

2.3 Soil preparation and characterization

In the results and discussion for this paper, the topsoil denotes the soil depth at surface (10–14 cm), and the subsoil describes the soil depths at 45–49 cm (mid-depth) and 85–89 cm (deep soil).

In the laboratory, we opened the polycarbonate cores to retrieve the 4 cm section where labeled roots were added (same for disturbance control). We also sampled the 4 cm section above and below the target depths. The soil samples were sieved <2 mm. Roots were picked off the top of the sieve by tweezers. Bulk soil < 2 mm was freeze-dried and re-weighed. A subsample of bulk soil samples was ground by a ball mill (MM400, Retsch, Haan, Germany) and analyzed for carbon and nitrogen concentrations, as well as stable carbon isotope composition (δ13C) using an elemental analyzer-isotope ratio mass spectrometer (EA-IRMS; Flash 2000-HT Plus, linked by Conflo IV to Delta V Plus isotope ratio mass spectrometer, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). The results are reported in the δ notation:

where Rsample and Rstandard are the 13C 12C ratios of the sample and the international standard, Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (VPDB, 0.01118), respectively. At least two analytical replicates were measured for all samples. Calibration was carried out using IAEA-certified primary standards (e.g., N600 caffeine) and caffeine (Merck) as secondary standard.

2.4 Analysis of hydrolysable lipids

All soil samples (<2 mm) were pre-extracted by Soxhlet following an established protocol (Wiesenberg and Gocke, 2017) to remove solvent-extractable lipids with dichloromethane : methanol (93:7; ) for 48 h. The extraction residues were dried until constant weight.

The extraction residues were homogenized with a ball mill (MM400, Retsch, Haan, Germany) and then hydrolyzed according to Zosso et al. (2023). Therefore, an aliquot of each residue equivalent to >20 mg carbon was weighed in a 250 mL round bottom flask. The sample was mixed with the extraction solution methanol: deionized water (9:1; ) with 6 % potassium hydroxide (KOH) and then saponified for 20 h at around 85–88 °C in a water bath under reflux. Subsequently, the solution was filtered and transferred to a separation funnel for phase separation. The solution was acidified to pH 2.0 using 6 M hydrochloric acid (HCl) and then extracted with dichloromethane. The collected fractions were volume-reduced and remaining water was removed by water-free sodium sulfate (Na2SO4).

For quantification of hydrolysable lipids, deuterated eicosanoic acid (D39C20; Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc.) was added to the samples as an internal standard. The samples were silylated at 80 °C for 1 h with bis(trimethylsilyl)acetamide (BSA; Wiesenberg and Gocke, 2017). Individual compounds were quantified on an Agilent 7890B gas chromatograph (GC) equipped with a multi-mode inlet and a flame ionization detector (FID). Compound identification was performed on an Agilent 6890N GC equipped with split/splitless inlet and coupled to an Agilent 5973 mass selective detector (MS). Compounds were identified by comparison of mass spectra with those of external standards and from the NIST and Wiley mass spectra library. Both instruments were equipped with DB-5MS columns (50 m × 0.2 mm × 0.33 µm) and 1.5 m de-activated pre-columns, with helium as the carrier gas (1 mL min−1). Silylated fractions were injected in splitless mode at an initial GC oven temperature of 50 °C that was kept isothermal for 4 min, then increased to 150 °C at a rate of 4 °C min−1. Thereafter, the temperature ramped up to 320 °C at a rate of 3 °C min−1 and held for 40 min. The GC-MS was operated in electron ionization mode at 70 eV and scanned from 60–650. The analysis of the data was processed with Agilent Chemstation software. The concentration of each compound was finally normalized to the organic carbon concentration of the respective sample (stated as µg g−1 OC). The weight of samples weighed in for hydrolyzation is always corrected by accounting for the mass loss due to free lipid extraction:

where Mcorrected is the corrected weight of soil samples, Mweighed is the weight of soil samples weighed in for hydrolyzation, and pfree lipids is the proportion of free extractable lipids to the mass of soil samples weighed in for Soxhlet extraction.

In this paper, mid-length and long-chain monomers are the compounds with a carbon chain length n between 14 and 20 () and length ≥ 20, respectively. For each compound class, fatty acids are the synonymously used for n-carboxylic acids, ω-hydroxy acids are short for ω-hydroxy carboxylic acids, diacids stand for α, ω-alkanedioic acids, alcohols are abbreviated for n-alcohols, and mid-chain acids stand for mid-chain hydroxylated fatty acids, referring to fatty acids with functional groups or structural modifications located in the middle of their carbon chain, typically at the C-9 and C-10 carbon positions, such as x, ω-dihydroxyhexadecanoic acid (x=9 or 10; Graça, 2015).

Different monomers can be used as markers for leaf and needle (cutin) or woody and root (suberin) biomass. However, there are no universal markers across a variety of studies since the relative proportions of cutin and suberin markers could vary among plant taxa, plant functional type or plant organ (Jansen and Wiesenberg, 2017; Mueller et al., 2012). Here, we selected ω-hydroxy alkanoic acids and diacids as suberin markers since these monomers exist in substantial amount in the roots of the dominating plant species around the experiment plots and are 10 times higher in concentration compared to the same monomers in leaves or needles in the same species (Fig. S2). Cutin markers could not be distinguished since all the mid-chain acids which were traditionally considered as cutin markers were present in considerable amounts in added 13C-labeled roots (Table S1 in the Supplement).

To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies reporting the composition of mid-chain fatty acids, ω-hydroxy or diacids from microorganisms in soil, although it was reported that microorganisms can synthesize the compound classes mentioned above (Huf et al., 2011; Kim and Park, 2019). These compound classes, however, are more regio-specific (the enzymes will target only one or a few defined carbon positions) and differ from those in plants and animals (Kim and Oh, 2013) and usually have a carbon chain-length < 20 (Zhang et al., 2024). Therefore, we hypothesize that all the compounds with a carbon chain length ≥ 20 and mid-chain fatty acids are exclusively plant-derived.

2.5 Compound-specific isotope analysis

To determine the δ13C of individual compounds, a Trace GC Ultra, coupled via GC Isolink II and Conflo IV to Delta V Plus isotope mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to perform compound-specific δ13C analysis of individual hydrolysable lipids. The settings of the instrument and temperature program used here was the same as mentioned above. Reproducibility and stability (<0.6 ‰) of δ13C values were checked with pulses of CO2 reference gas and n-alkane standard mixture (C20–30; Sigma Aldrich) of known isotope composition. The δ13C values were presented in per mil (‰) relative to the Vienna-Pee Dee Belemnite (V-PDB) reference standard. Every sample was measured with three analytical replicates and the difference between measurements typically did not exceed 1.0 ‰ for natural abundance samples and 10 % of the measured isotope value for 13C labeled samples.

2.6 Calculations

The isotope composition of individual hydrolysable lipids was corrected for the value of the δ13C value of each trimethylsilyl group that was added during silylation as:

where n is the number of carbon atoms in the underivatized hydrolysable lipids and δUD and δD are isotope ratios of the underivatized and the derivatized hydrolysable lipids, respectively, a is the number of functional groups in individual compounds that were derivatized by BSA. δM is the carbon isotope ratio of the added trimethylsilyl group (−44.3 ‰). δM was determined by repeated measurement (n=8, with 3 analytical replicates of each) of derivatized standard FAs (C10 and C12 FAs with known δ13C isotope composition).

The 13C-excess, which can be expressed as percent atom excess, presents the enrichment of 13C in individual hydrolysable lipids. The value is defined as the ratio of the relative abundance of the heavier stable isotope in a labeled sample to the natural isotope abundance in the identical unlabeled sample (Epron et al., 2012). It was calculated as followings (Speckert et al., 2023):

where 13C 12Cdistcontrol is the atomic ratio of the stable isotopes in the compartments (bulk soil carbon, and individual monomers of hydrolysable lipids) of the disturbance control plots as natural abundance values, and 13C 12Clabeled is the atomic ratio in the corresponding compartments in the plots with added labeled root litter.

As individual isotope values can vary a lot in between different homologues for each compound-class specifically in isotope labeling experiments, a more meaningful measure was chosen to express the δ13C values of the respective compound-classes that can be assigned to the same carbon source (Wiesenberg et al., 2008). The δ13C values and 13C-excess for the most abundant compound classes (n-alcohols, n-fatty acids, diacids, and ω-hydroxy acids) within the hydrolysable lipid fractions were calculated separately as weighted means of individual compounds within each compound class. This means within each compound class, weightings will be given to each monomer in this compound class (e.g., ω-hydroxy acids) based on the proportional contribution of individual monomer (e.g., C24 ω-hydroxy acids) to the total concentration of this compound class. Then for individual monomers, their weightings will be multiplied by their δ13C values, and we sum up all the monomers identified to get the weighted mean δ13C values for this compound class:

where μ denotes the average value and subscript “c” represents different compound classes, x denotes the value of either δ13C or 13C-excess, a and b represent the lower and upper limits of the respective carbon number range, wi indicates the relative abundance of the individual compounds within compound class c.

The amount of root carbon that was recovered in bulk soil was calculated by dividing the amount of 13C-labeled root-derived carbon left in the soil by the amount of carbon added with the original labeled roots. The proportion of root-derived carbon (froot) was estimated by using a simple mixing model (Hicks Pries et al., 2018):

where 13C atom %sample is the 13C atom % of soil samples where labeled root litter was added; 13C atom %DC is the 13C atom % of soil samples in the disturbance control plots; 13C atom %root is the 13C atom % of initial 13C labeled roots; fsoil and froot are the proportion of carbon originally derived from native soil and labeled root litter, respectively. Msoil is the mass of the soil sample and C %soil is the carbon content of the corresponding soil sample. 0.14 is the mass of root litter (g) added at individual soil depth and 0.463 is the carbon content of the added root litter.

The decay rate, k, of initially added 13C-labeled roots and root-derived hydrolysable lipids was calculated based on the following model (Olson, 1963):

where M0 is the mass of original roots or root-derived hydrolysable lipids, Mt denotes the mass of root-derived carbon or hydrolysable lipids at time t, and t is the duration of incubation which is 3 years in our study. The model assumes that M is a well-mixed carbon pool with first-order decay kinetics. The residence time is the reciprocal of k.

The priming effect of added 13C labeled root litter was calculated using the mass of carbon in DC cores at individual depths as background values. Then, based on the calculations shown in Eq. (6), the proportion of native SOM that is left in the labeled cores within the same plot after 3 years of incubation was calculated:

where MSOMl and MSOMDC denote native SOM left in labeled cores and SOM in DC cores, respectively. The priming effect for hydrolysable lipids was calculated with the same approach. One outlier is excluded in priming effect calculation at mid-depth in ambient plots. It is noteworthy that this is only an estimated proxy used for priming effect. The more classical and straightforward way to calculate priming effect is described in Schiedung et al. (2023).

2.7 Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in the RStudio interface 2024.12.1.563 (Posit team, 2025) with R version 4.4.2 (R Core Team, 2024). We used linear mixed effects models (LMEs) in the “nlme” package (v3.1.166; Pinheiro et al., 2024) to test the fixed effects on responsive variables. All the plots were created using the “ggplot2” package (v3.5.1; Wickham, 2016). Homoscedasticity and normality were visually checked by residual plots and Q–Q plots. If model assumptions were not met, the data was log-transformed.

Response of bulk soil organic carbon concentration was tested to warming, root treatment, depth, and their interaction. 13C-excess was tested in response to warming, depth, and their interaction. The hydrolysable lipids concentration normalized to soil organic carbon (SOC; mg g−1 SOC) was tested in response to warming, root treatment, depth, and their interaction. We tested warming, depth, and their interaction on hydrolysable lipids mass change, and 13C-excess of each compound class separately. To test whether chain length increases suberin-derived monomers resistance to decomposition, we used warming, depth, carbon number (refers to the total number of carbon atoms in the backbone of the respective suberin monomers), and their interactions as fixed effects to evaluate their effects on mass change of individual ω-hydroxy acid and diacid monomers. For each statistical test, we regarded block as a random effect.

Model fits were evaluated by Akaike's Information Criterion (AIC; Akaike, 1998). We conducted a backward stepwise model selection to remove fixed effects that increased AIC values by 5 or more (Pegoraro et al., 2024). The alpha level was set to α=0.05 as significant in all statistical tests and a p between 0.05–0.1 was considered marginal.

3.1 Soils without root litter incubation

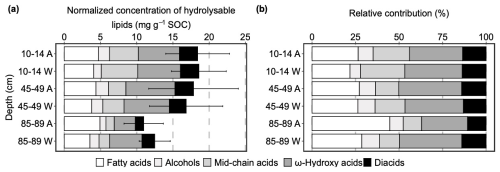

In ambient plots, the normalized hydrolysable lipids concentration decreased from 18.4±4.4 mg g−1 SOC in topsoil to 11.0±2.7 mg g−1 SOC in the deep soil, whereas it decreased from 18.6±3.8 mg g−1 SOC in topsoil to 12.5±2.1 mg g−1 SOC in the deep soil in warmed plots (Fig. 1a). However, this average decrease of hydrolysable lipids concentration with depth was not significant (p=0.460; Table S10). Warming did not significantly alter the normalized hydrolysable lipids concentration (p=0.472; Table S10) across the soil profile.

Figure 1(a) Hydrolysable lipids normalized to soil organic carbon (SOC) concentrations (mg g−1 SOC) in disturbance control (DC) with ambient temperature (A) and warming (W) in 2019 after 3 years in-situ incubation (mean ± SE, n=3); (b) proportions of individual compound classes to total hydrolysable lipids identified in DC cores (mean, n=3). For clarity of the visual presentation SE error bars are shown cumulatively.

In general, warming did not significantly alter the relative contribution of each compound class to the total hydrolysable lipids (p>0.1; Table S21) and depth only significantly decreased proportion of mid-chain acids (p=0.003; Table S21). In ambient topsoil, ω-hydroxy acids accounted for the largest proportion of total hydrolysable lipids by 31 %, followed by fatty acids (27 %), mid-chain acids (21 %), diacids (13 %), while alcohols only make up 9 % of the total (Fig. 1; Table S22). At the same depth, warming did not significantly affect the relative contribution of each compound class (p>0.1; Table S22). At mid-depth (45–49 cm), the proportion of each compound class to total hydrolysable lipids was consistent compared to topsoil although contribution of mid-chain acids marginally decreased by 7 % (p=0.072; Table S22). In the deep soil (85–89 cm), the proportion of mid-chain acids further significantly decreased by 10 % compared to its contribution in topsoil (p=0.011; Table S22). Albeit much higher average contribution of fatty acids (45 %) in ambient deep soil, it did not significantly differ relative to topsoil (p=0.360; Table S22). At this depth, warming did not significantly alter the proportions of all the compound classes. However, elevated temperature marginally decreased fatty acids and increased diacids proportion by 16 % (p=0.084; Table S23) and 3 % (p=0.064; Table S23), respectively.

3.2 Soils with root litter incubation

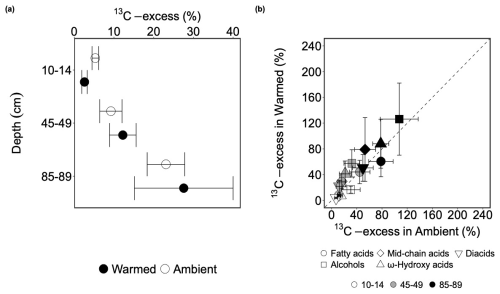

13C-excess of bulk SOC did not significantly change with warming (p=0.527; Table S8) but increased significantly with depth (p=0.001; Table S8). At 10–14 cm, the 13C-excess of bulk SOC was on average 17.0 % lower in warmed than in ambient plots (Table S9), but this difference was not significant (p=0.527; Table S8). At 45–49 cm, 13C-excess of bulk SOC on average increased by 2.7 times from 3.8 % in topsoil to 10.5 % at this depth (p=0.016; Fig. 2; Table S9). In the deep soil, the 13C-excess on average furthered increased to 22.8 % (Fig. 2).

Figure 2(a) The presence of carbon derived from the 13C-labeled root in the bulk soil after 3 years of incubation, expressed as 13C-excess of bulk soil carbon (mean ± SE, n=3) at 10–14, 45–49, 85–89 cm depth in 2019 in ambient plots (white circles) and warmed plots (black circles). (b) Comparing the means of weighted 13C-excess of each compound class from warmed plots (y-axis) and ambient plots at three depths (10–14, 45–49, 85–89 cm) with a 1:1 line (mean ± SE, n=3). Values above the 1:1 line indicate higher values in warmed plots than in ambient plots and values below the 1:1 line indicate the opposite.

Similar to bulk SOC, the weighted 13C-excess of each compound class was not significantly altered by warming (p>0.05; Table S12) but significantly increased with depth (p<0.05; Fig. 2b; Table S12). In topsoil, warming on average decreased weighted 13C-excess for all the compound classes between 3.2 % (diacids) and 8.5 % (alcohols) compared to ambient conditions, however, this decrease was not significant (p>0.1; Table S12). At 45–49 cm, warming non-significantly increased weighted 13C-excess for all the compound classes (p>0.1; Table S14), except for fatty acids, where warming on average decreased their weighted 13C-excess (p=0.920; Table S14). In the deep soil, warming on average largely reduced the weighted 13C-excess of fatty acids (28.0 %; p=0.356; Table S14), ω-hydroxy acids (17.1 %; p=0.728; Table S14), and diacids (8.2 %; p=0.760; Table S14), and slightly lower the weighted 13C-excess of alcohols (0.9 %; p=0.989; Table S14) and mid-chain acids (3.0 %; p=0.925; Table S14), although none of them was significant. The weighted 13C-excess of fatty acids increased significantly from 10–14 o 45–49 cm by 25.5 % (p=0.039; Table S13), whereas the weighted 13C-excess all the other compound classes non-significantly (p>0.1; Table S13) increased between 2.5 % (alcohols; Table S13) to 3.2 % (diacids; Table S13) at the same depth. At 85–89 cm, the weighted 13C-excess of fatty acids, ω-hydroxy acids, and diacids significantly increased compared to the values at 10–14 cm by 62.2 % (p=0.004; Table S13), 62.9 % (p=0.033; Table S13), and 38.1 % (p=0.015; Table S13), respectively. The weighted 13C-excess of alcohols and mid-chain acids marginally increased by 73.3 % and 36.7 % correspondingly (p=0.054 and 0.051, respectively; Table S13) at the same depth.

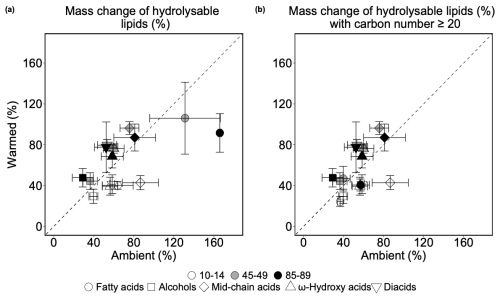

The mass change of each compound class represents the proportion of hydrolysable lipid-derived compound classes from the 13C-labeled root litter that remained after 3 years of incubation (Fig. 3). This metric allowed us to evaluate whether these compound classes experienced a net loss or accumulation during the incubation. Values above and below 100 % indicates accumulation and loss of corresponding compound classes, respectively.

The mass changes of different compound classes were affected differently by warming and soil depth. Both warming (p=0.035; Table S15) and depth (p=0.008; Table S15) had significant impacts on fatty acid mass change and the impacts of warming was independent from depth (p=0.409; Fig. 3a, Table S15). Fatty acids significantly accumulated across the soil profile, resulting in an increased their mass change by 67 % (p=0.044; Table S16) and 102 % (p=0.006; Table S16) at mid-depth and in the deep soil, respectively. Although non-significantly at 10–14 and 45–49 cm, warming lead to a consistent decreased fatty acid mass change across the soil profile, particularly at 85–89 cm, where there was a significant lower (74 %; p=0.029; Table S17) recovered fatty acids with elevated temperature. The accumulation of fatty acids at 45–49 and 85–89 cm derived primarily from Hexadecanoic acid (n-C16:0), Octadecanoic acid (n-C18:0), and Octadecenoic acid (n-C18:1), where the mass change of these monomers exceeded 110 % or even 300 % (Table S2), e.g. Octadecanoic acid (n-C18:0) at 85–89 cm in ambient and warmed plot (348±49 % and 181±24 %; Table S2).

The effects of warming on the mass change of mid-chain acids were marginally depth-dependent (p=0.057; Table S15). In the topsoil, warming significantly decreased the mid-chain acids recovered from hydrolysable lipids (p=0.029; Table S17), whereas warming non-significantly increased the mass change of this compound class at 45–49 cm (p=0.257; Table S17) and at 85–89 cm (p=0.729; Table S17). Neither warming nor depth had significant effects on the mass changes of all the other three compound classes (p>0.1; Table S15). There was a general trend that warming on average decreased the mass changes of alcohols, ω-hydroxy acids, and diacids in the topsoil, but increased them at mid-depth and in the deep soil (Table S17), however, none of these changes were significant (p>0.1; Table S15).

Figure 3(a) Comparing mean of mass change (%) of each compound class in 13C-labeled root-derived hydrolysable lipids (n=3). Values above the 1:1 line indicate higher values in warmed plots than in ambient plots and values below the 1:1 line indicate the opposite. (b) Comparing mean of mass change (%) of each compound class in 13C-labeled root-derived hydrolysable lipids (carbon number ≥ 20 for fatty acids, ω-hydroxy acids, and diacids; n=3). In both plots, the error bars denote the standard error of each compound class in ambient and warmed plots in the individual soil depths. Values smaller than 100 % indicate a loss and those larger than 100 % indicate a gain of this compound class. Values above the 1:1 line indicate higher values in warmed plots than in ambient plots and values below the 1:1 line indicate the opposite.

For fatty acids with a carbon number ≥ 20, we did not observe significant warming effects on the mass change (p=0.255; Fig. 3b, Table S18), but marginal depth effects (p=0.076; Table S18). Warming on average reduced the mass change of fatty acids by 12 % at 10–14 cm, 7 % at 45–49 cm, and 16 % at 85–89 cm, but these effects were non-significant (p=0.260, 0.501 and 0.141, respectively; Table S20). Similar to fatty acids, there was no significant effects of neither warming nor depth on the long-chain ω-hydroxy acids and diacids mass change, and warming effects was not dependent on depth (p>0.1; Table S18). At 10–14 cm, warming led to non-significant decreases in the ω-hydroxy acids and diacids mass change by 16 % and 22 % (p=0.334 and 0.316, respectively; Table S20). In contrast, although warming on average enhanced the mass change of the two compound classes at both 45–49 and 85–89 cm, none of the changes were statistically significant (p>0.1; Table S20).

3.3 Priming effect

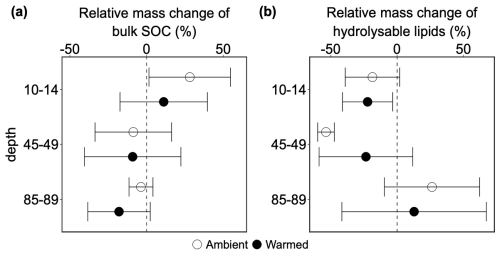

Neither depth nor warming had significant impacts on the mass differences of pre-existing SOC (p=0.558 and 0.422, respectively; Table S24). In topsoil, labeled root addition led to SOC accumulation on average by 28 % in ambient plots, but this accumulation was not significant (p=0.273; Table S25). The effects of root addition decreased on average by 37 % at mid-depth and 32 % at 85–89 cm, resulting in an on average loss of pre-existing SOC (Fig. 4a). However, these effects were non-significant (p=0.359 and 0.375, respectively; Table S25). Warming caused an average decline of the bulk SOC mass change at 10–14 and 85–89 cm by 17 % and 14 % (Fig. 4a), and no-change at mid-depth, but none of them were significant (p=0.629, 0.684 and 0.991 for 10–14, 85–89, and 45–49, respectively; Table S26).

Figure 4Relative mass difference of: (a) pre-existing bulk soil organic matter and (b) hydrolysable lipids between cores with and without addition of 13C-labeled root litter (labeled – disturbance control cores). Negative values indicate the accelerated decomposition of pre-existing soil organic carbon (positive priming effect). Positive values indicate inhibition (negative priming) of decomposition (mean ± SE, n=3).

The similar trend was observed for the mass change of pre-existing hydrolysable lipids as for pre-existing SOC, but the direction was opposite in the topsoil and the deep soil (Fig. 4b). Neither depth nor warming significantly altered the relative mass differences of pre-existing hydrolysable lipids (p=0.310, and 0.987 for depth and warming, respectively; Table S24). At 10–14 cm, labeled root addition led to a non-significant 19 % loss of pre-existing hydrolysable lipids (p=0.596; Table S25). In the subsoil, the responses of relative hydrolysable mass change were contrasting between 45–49 and 85–89 cm. At mid-depth, labeled root addition caused a further non-significant decrease of the mass change of hydrolysable lipids by 35 % (Fig. 4b; p=0.529; Table S25), whereas in the deep soil, it caused a non-significant increase of the hydrolysable lipids mass change by 45 % compared to topsoil (Fig. 4b; p=0.372; Table S25). In the topsoil, warming non-significantly decreased the mass change of hydrolysable lipids by 4 % (p=0.941; Table S25). In the subsoil, warming had also contrasting effects on the mass change of hydrolysable lipids (Fig. 4b) between mid-depth and deep soil. Warming on average increased the mass change of hydrolysable lipids at 45–49 cm by 30 % and decreased it by 14 % compared to corresponding ambient conditions, but none of them was significant (p=0.587 and 0.784, respectively; Table S26).

4.1 Warming on hydrolysable lipids mass change was compound-dependent

4.1.1 Warming significantly attenuated the accumulation of fatty acids in subsoil

The effects of soil warming on the decomposition of labeled root-derived hydrolysable lipids varied by compound class. Warming significantly decreased the mass change of fatty acids, independent of soil depth. In the topsoil (10–14 cm), although non-significantly, warming reduced mass change of fatty acids by 24 %, likely due to enhanced microbial decomposition. Similar acceleration of plant-derived input decomposition under warming has been reported at this site (Ofiti et al., 2021; Soong et al., 2021). In the topsoil, warming both increased carbon stocks and particulate organic matter, which is readily available substrates to microorganisms (Soong et al., 2021), and maintained microbial abundance while shifting microbial community structure toward taxa capable of degrading wider range of substrates (Dove et al., 2021; Zosso et al., 2021). Actinobacteria, known for breaking down complex carbon (DeAngelis et al., 2015; Goodfellow and Williams, 1983), increased in relative abundance under warming in our study (Pegoraro et al., 2024).

In the subsoil (45–49 and 85–59 cm), fatty acid mass change exceeded 100 %, indicating accumulation of this compound class from other sources. This accumulation derived primarily from octadecanoic acid, octadecenoic acid, and hexadecanoic acid (C18:0 fatty acids, C18:1 fatty acids, and C16:0 fatty acids, respectively; Table S2), which originate from both plant and microbial biomass. In contrast, long-chain fatty acids (carbon number ≥ 20), typically enriched in higher plant tissues (Harwood and Russell, 1984), did not accumulate. Therefore, the exceeding fatty acids originated likely from microorganisms, e.g. through phospholipid fatty acids synthesized during microbial growth (Joergensen, 2022; Zelles, 1997). 13C-labeled substrate could be utilized by microorganisms and incorporated in microbial membrane lipids (Gunina et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2020). In our study, warming attenuated the accumulation of fatty acids in the subsoil, particularly at 85–89 cm, where there was a significant decline of the mass change of this compound by 74 %. This significant decrease implied a restricted decomposition of added root litter.

This pattern aligned with the concurrent observations from Pegoraro et al. (2024), who observed higher phospholipid fatty acid concentrations and stronger 13C-enrichment of fungal markers in ambient subsoil following root litter addition. Fungi preferentially utilized new plant-derived inputs (Lindahl et al., 2007) and incorporate these substrates into their biomass (Williams et al., 2006). Warming reduced fungal relative in the subsoil (Pegoraro et al., 2024), potentially slowing root litter decomposition and lowering fatty acid mass change. Additionally, warming reduced soil moisture by 18 % at mid-depth and 32 % in the deep soil horizon in our study (Pegoraro et al., 2024), which may have limited substrate and enzyme mobility, consequently restricting microbial access to fresh plan inputs, and thereby microbial decomposition (Manzoni et al., 2012b; Védère et al., 2020).

4.1.2 No significant change of suberin markers in subsoil with warming

In contrast to fatty acids, warming had no significant influence on the decomposition of alcohols, mid-chain acids, ω-hydroxy acids, and diacids, although the effect on mid-chain was marginally depth-dependent (p=0.057; Table S15). This lack of warming effect persisted also when focusing on ω-hydroxy acids, and diacids with carbon numbers ≥ 20 (Table S20), which are typically identified as suberin markers (Angst et al., 2016b; Franke et al., 2005; Mendez-Millan et al., 2011). These results suggested that warming did not alter the decomposition of added 13C-labeled root litter across the soil depths after 3 years of incubation (Pegoraro et al., 2024).

Prior studies have reported contrasting hydrolysable lipid responses to warming. At the temperate forest site studied here, Zosso et al. (2023) have discovered a significant loss of hydrolysable lipids by 28 % in the subsoil after 4.5 years of warming, attributed primarily to increased fine root mortality caused by warming (Ofiti et al., 2021). The discrepancy between our findings may arise from methodological differences that our approach involved mixing 13C-labeled root litter into the soil, which may have reduced the spatial accessibility of microorganisms to fresh substrates, an effect potentially further amplified by the warming-induced declines in subsoil microbial abundance (Zosso et al., 2021). In another study in a hardwood forest, 14 months of warming did not affect suberin markers (Feng et al., 2008), whereas in a mixed hardwood forest, warming significantly decreased suberin concentration after 4 years of warming (Pisani et al., 2015), however, this pattern was not significant in the long-term (vandenEnden et al., 2021). Divergent results indicate that the responses of hydrolysable lipids to soil warming are dependent on various factors, e.g. experimental methods, vegetation, and duration of the experiment.

The unchanged suberin markers, coupled with significantly lower recovery of fatty acids in warmed relative to ambient subsoil, indicates a potential shift in SOC processing pathways at these depths. In general, microbial carbon use efficiency (CUE) declined with soil depth (Pei et al., 2025; Spohn et al., 2016), a pattern also observed at our study site (Dove et al., 2021). Yet, the effect of warming on CUE remains uncertain (Zhang et al., 2022). If warming reduced microbial CUE in our incubation experiment, as observed elsewhere (Li et al., 2019, 2024; Manzoni et al., 2012a), this could partly explain the greater fatty acid accumulation in the ambient subsoil. A decline in CUE under warming would favor microbial respiration over growth, thereby reducing the incorporation of substrates into microbial biomass (Manzoni et al., 2012a). Given the paucity of warming studies examining subsoil CUE, and its pivotal role in carbon storage (Tao et al., 2023), targeted experiments are needed to test this hypothesis in the future.

4.2 Suberin markers' resistance to decomposition increased with chain length

To further explore other factors governing the decomposition of suberin markers in our study, we examined the effects of chain length (number of carbon atoms in each monomer) on the mass change of ω-hydroxy acids and diacids after 3 years of incubation. Chain length had a significant effect on the mass change of suberin markers (p<0.001; Table S27) that they decomposed more slowly with longer chain length. This pattern is independent of warming, depth, and compound class. Our results are in line with multiple previous studies, which also reported decreased decomposability of hydrolysable lipids with increasing chain length by examining either single compound class (Kashi et al., 2023), or suberin- and/or cutin-derived polymers (Altmann et al., 2021; Angst et al., 2016a; Suseela et al., 2017). Generally, molecules with a low oxidation state or low O C ratio (i.e., more reduced compounds such as lipids) provide less favorable energy yields for microbial oxidation, which often translates into slower decomposition rates (Kleber, 2010; LaRowe and Van Cappellen, 2011). As chain length increases, the carbon atoms in respective compound classes exhibit progressively lower oxidation states (Chakrawal et al., 2020). Therefore, the microbial utilization of long-chain lipids requires more energy investment than that of mid-chain lipids (Schönfeld and Wojtczak, 2016), which may explain the slower decomposition of long-chain ω-hydroxy acid and diacid observed in our study.

It is noteworthy that when chain length was tested together with warming and depth on the mass change of ω-hydroxy acids and diacids monomers, warming emerged as a significant factor (p<0.001; Table S27), and its effect was depth-dependent (p<0.001; Table S27). Specifically, warming significantly enhanced the loss of suberin monomers in the topsoil (p=0.002; Table S29), but reduced it at 45–49 and 85–89 cm (p<0.001 and p=0.008, respectively; Table S29). This pattern was also observed at compound class level, although with limited statistical power due to limited number of replicates. The stronger statistical significance at the monomer level reflects the greater number of observations (i.e., higher degree of freedom) and lower variability within individual monomers compared to the aggregated variability among monomers when grouped at the compound class level. Therefore, our results can confirm that the effect of warming on suberin marker decomposition was depth-dependent.

Root-derived hydrolysable lipids, especially those suberin markers, degraded more slowly than bulk root carbon, indicated by higher proportions of hydrolysable lipids remaining in the soil than the bulk root recovery (Pegoraro et al., 2024). The depth-dependent effects of warming lead to depth-specific mean residence time (MRT) of these suberin markers (chain length ≥ 20). In the topsoil, warming reduced the MRT of ω-hydroxy acids and diacids due to accelerated decomposition from 5.8 and 5.6 years in ambient plots to 3.4 and 3.6 years. In the subsoil, slower decomposition of suberin markers caused by warming enhanced MRT compared to ambient conditions, particularly at 45–49 cm with warming, where the MRT for of ω-hydroxy acids and diacids was 11.9 and 15.0 years, respectively.The suberin markers had a shorter MRT in our study compared to a previous study, where Feng et al. (2010) reported a decadal MRT of hydrolysable lipids between 32 to 34 years. This discrepancy could be related to the fact that our model substrates are grass roots (Avena fatua) with less lignin and lower C N ratios than local woody roots (Hicks Pries et al., 2018; Silver and Miya, 2001). Hydrolysable lipids without association to lignin could be steadily decomposed (Angst et al., 2016a). Additionally, an underestimation of MRT could exist in our study since we have a much shorter experimental duration compared (Feng et al., 2010).

In prior study, Suseela et al. (2017) reported that elevated temperature and CO2 increased the chain length of ω-hydroxy acids in grass roots (Boutelou gracilis). Together with our finding that the decomposability of suberin markers decreases with chain length, this raises the possibility that plant physiological adaptations to future warming could enhance the persistence of root compartments against microbial decomposition and consequently mitigate potential soil carbon losses under warming.

4.3 No priming effect of added 13C-labeled root litter after 3 years of incubation

Fresh biomass input can stimulate (prime) the decomposition of native, pre-existing SOM. This is especially relevant in subsoils, where SOM might have existed for a long time, from decades to millennia (Fontaine et al., 2007; Luo et al., 2019; Shahzad et al., 2018). Such priming could offset long-term carbon sequestration, especially in subsoil where there is usually substrate limitation (Bernard et al., 2022; Bingeman et al., 1953).

Three years after adding 13C-labeled root at three different soil depths, we found no evidence for significant priming across the whole soil profile, either for pre-existing bulk carbon or hydrolysable lipids. This likely reflects the fact that fresh input was added only at the beginning of the incubation. Priming is a transient response to fresh carbon input (Schiedung et al., 2023) and is commonly strongest at the beginning of the incubation (Fontaine et al., 2007; Tao et al., 2024), a pattern that has been also reported in lipid decomposition experiments (Angst et al., 2016a; Kashi et al., 2023). Therefore, any initial effect may have dissipated in the long-term. In addition, our calculations of priming effects showed large error bars, likely due to heterogeneous background SOC concentrations, particularly in the subsoil. For example, the mass of SOC in root litter added to the topsoil (10–14 m) represented only 4.0 %–8.5 % of pre-existing SOC, whereas at 85–89 cm, the same litter addition corresponded to 10.5 %–39.3 % of pre-existing SOC. This wide range in the proportion of added to native SOC, alongside reduced microbial abundance under warming may have biased our estimates and masked potential priming effects. Therefore, although our back-of-the-envelope calculation provides a preliminary estimate, the strength of the interpretation is limited. Short-term monitoring of CO2 fluxes and their partitioning between 13C-labeled root- and native SOC-derived, would offer more robust insights into whether root litter addition primes native SOC decomposition, particularly in the subsoil.

Our experiment is among the first in-situ, long-term incubations to investigate the effect of warming on the decomposition of simulated new substrates input across different soil horizons under natural field conditions. Using compound-specific isotope analysis with specific focus on root-derived molecular markers, we traced their fates through microbial mineralization, assimilation and/or stabilization via e.g. aggregate occlusion, and organo-mineral association (Pegoraro et al., 2024). Distinct responses among compound classes across soil depths and temperature treatments improved our understanding of how warming shifts the fate of root-derived molecular markers. Therefore, we recommend applying this technique or more advanced variants, such as position-specific 13C-labeling, in the future to better understand soil carbon dynamics under climate change. Position-specific 13C-labeling technique can pinpoint which substrates or carbon functional groups are more rapidly mineralized, incorporated into microbial biomass, or associated with minerals (Apostel et al., 2015; Kashi et al., 2023; Schink et al., 2021).

Three years of incubation enabled us to track the fate of 13C-labeled root litter and assess long-term dynamics of relatively stable compounds like hydrolysable lipids in the soil. Collectively, at the compound class level, hydrolysable lipids showed compound class-dependent responses to warming. Warming had the most pronounced effects on fatty acids, consistently decreasing their mass change across the soil profile. However, the mechanisms were fundamentally different between top- and subsoil. In the topsoil, enhanced microbial decomposition accelerated fatty acid losses. In the subsoil, where there was accumulation of fatty acids, warming attenuated this accumulation, particularly at depth, coincident with lower microbial abundance and constrained hydrolysable lipids decomposition due to low soil moisture. At the monomer level, suberin markers, ω-hydroxy acids and diacids, were more resistant to decomposition than bulk root-derived carbon, with their resistance increasing with chain length. Moreover, warming exhibited depth-dependent effects on the decomposition of suberin-derived monomers–significantly accelerated their decomposition in the topsoil while suppressing it in the subsoil.

Substantial spatial heterogeneity was observed, especially in the subsoil, and this heterogeneity was partially reflected by wide range of added carbon to background SOC ratios. The disproportionate carbon inputs across depths may have biased our results, particularly in subsoil where higher soil moisture and microbial abundance under ambient conditions favored microbial decomposition. Along with the limited number of observations in our study, the capability to generalize our findings is constrained. Therefore, future in-situ warming experiments with greater emphasis on subsoil processes and enhanced replications are needed corroborate our findings.

The data used in this study are available from the ESS-DIVE repository (https://data.ess-dive.lbl.gov/datasets/doi:10.15485/2997759, last access: 8 October 2025).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-11-1077-2025-supplement.

BS conducted lipids analysis and data interpretation, contributed to writing original draft, statistical analysis, and editing. EP shared resources and contributed to statistical analysis, writing review, and editing. MST applied for the funding, designed and maintained the warming experiment, contributed to statistical analysis, and writing review. CUZ conducted elemental analysis, introduced lipid analysis to me, and contributed to conceptualization, writing review and editing. GLBW supervised BS through the lipid analysis, contributed to methodology, conceptualization, data interpretation and validation, writing review, and editing. MWIS applied for funding and conceived DEEP C project, contributed to conceptualization, data interpretation, writing review, and editing.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We thank Nicholas Ofiti, Tatjana Speckert for introduction and help of lipid analysis methods, Thomas Keller, Barbara Siegfried and Yves Brügger for lab support.

This research has been supported by the Schweizerischer Nationalfonds zur Förderung der Wissenschaftlichen Forschung (grant no. 200021_172744) and the Biological and Environmental Research (grant no. DE-AC02-05CH11231).

This paper was edited by Hu Zhou and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Akaike, H.: Information Theory and an Extension of the Maximum Likelihood Principle, in: Selected Papers of Hirotugu Akaike, edited by: Parzen, E., Tanabe, K., and Kitagawa, G., Springer, New York, NY, 199–213, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-1694-0_15, 1998.

Altmann, J. G., Jansen, B., Palviainen, M., and Kalbitz, K.: Stability of needle- and root-derived biomarkers during litter decomposition, J. Plant. Nutr. Soil. Sci., 184, 65–75, https://doi.org/10.1002/jpln.201900472, 2021.

Angst, G., Heinrich, L., Kögel-Knabner, I., and Mueller, C. W.: The fate of cutin and suberin of decaying leaves, needles and roots – Inferences from the initial decomposition of bound fatty acids, Org. Geochem., 95, 81–92, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2016.02.006, 2016a.

Angst, G., John, S., Mueller, C. W., Kögel-Knabner, I., and Rethemeyer, J.: Tracing the sources and spatial distribution of organic carbon in subsoils using a multi-biomarker approach, Sci. Rep., 6, 29478, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29478, 2016b.

Apostel, C., Dippold, M., and Kuzyakov, Y.: Biochemistry of hexose and pentose transformations in soil analyzed by position-specific labeling and 13C-PLFA, Soil Biol. Biochem., 80, 199–208, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.09.005, 2015.

Arndal, M. F., Tolver, A., Larsen, K. S., Beier, C., and Schmidt, I. K.: Fine root growth and vertical distribution in response to elevated CO2, warming and drought in a mixed heathland–grassland, Ecosystems, 21, 15–30, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-017-0131-2, 2018.

Bernard, L., Basile-Doelsch, I., Derrien, D., Fanin, N., Fontaine, S., Guenet, B., Karimi, B., Marsden, C., and Maron, P.-A.: Advancing the mechanistic understanding of the priming effect on soil organic matter mineralisation, Funct. Ecol., 36, 1355–1377, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.14038, 2022.

Bingeman, C. W., Varner, J. E., and Martin, W. P.: The effect of the addition of organic materials on the decomposition of an organic soil, Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 17, 34–38, https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1953.03615995001700010008x, 1953.

Bird, J. A. and Torn, M. S.: Fine Roots vs. Needles: A Comparison of 13C and 15N Dynamics in a Ponderosa Pine Forest Soil, Biogeochemistry, 79, 361–382, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-005-5632-y, 2006.

Button, E. S., Pett-Ridge, J., Murphy, D. V., Kuzyakov, Y., Chadwick, D. R., and Jones, D. L.: Deep-C storage: Biological, chemical and physical strategies to enhance carbon stocks in agricultural subsoils, Soil Biol. Biochem., 170, 108697, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2022.108697, 2022.

Castanha, C., Zhu, B., Hicks Pries, C. E., Georgiou, K., and Torn, M. S.: The effects of heating, rhizosphere, and depth on root litter decomposition are mediated by soil moisture, Biogeochemistry, 137, 267–279, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-017-0418-6, 2018.

Chakrawal, A., Herrmann, A. M., Šantrůčková, H., and Manzoni, S.: Quantifying microbial metabolism in soils using calorespirometry – A bioenergetics perspective, Soil Biol. Biochem., 148, 107945, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2020.107945, 2020.

Chen, Y., Han, M., Yuan, X., Hou, Y., Qin, W., Zhou, H., Zhao, X., Klein, J. A., and Zhu, B.: Warming has a minor effect on surface soil organic carbon in alpine meadow ecosystems on the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau, Glob. Change Biol., 28, 1618–1629, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15984, 2022.

DeAngelis, K. M., Pold, G., Topçuoğlu, B. D., van Diepen, L. T. A., Varney, R. M., Blanchard, J. L., Melillo, J., and Frey, S. D.: Long-term forest soil warming alters microbial communities in temperate forest soils, Front. Microbiol., 6, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2015.00104, 2015.

Dijkstra, F. A., Zhu, B., and Cheng, W.: Root effects on soil organic carbon: A double-edged sword, New Phytol., 230, 60–65, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17082, 2021.

Dove, N. C., Torn, M. S., Hart, S. C., and Taş, N.: Metabolic capabilities mute positive response to direct and indirect impacts of warming throughout the soil profile, Nat. Commun., 12, 2089, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22408-5, 2021.

Eckardt, N. A., Ainsworth, E. A., Bahuguna, R. N., Broadley, M. R., Busch, W., Carpita, N. C., Castrillo, G., Chory, J., DeHaan, L. R., Duarte, C. M., Henry, A., Jagadish, S. V. K., Langdale, J. A., Leakey, A. D. B., Liao, J. C., Lu, K.-J., McCann, M. C., McKay, J. K., Odeny, D. A., Jorge de Oliveira, E., Platten, J. D., Rabbi, I., Rim, E. Y., Ronald, P. C., Salt, D. E., Shigenaga, A. M., Wang, E., Wolfe, M., and Zhang, X.: Climate change challenges, plant science solutions, Plant Cell, 35, 24–66, https://doi.org/10.1093/plcell/koac303, 2023.

Eilers, K. G., Debenport, S., Anderson, S., and Fierer, N.: Digging deeper to find unique microbial communities: The strong effect of depth on the structure of bacterial and archaeal communities in soil, Soil Biol. Biochem., 50, 58–65, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.03.011, 2012.

Epron, D., Bahn, M., Derrien, D., Lattanzi, F. A., Pumpanen, J., Gessler, A., Hogberg, P., Maillard, P., Dannoura, M., Gerant, D., and Buchmann, N.: Pulse-labelling trees to study carbon allocation dynamics: A review of methods, current knowledge and future prospects, Tree Physiol., 32, 776–798, https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/tps057, 2012.

Fanin, N., Kardol, P., Farrell, M., Nilsson, M.-C., Gundale, M. J., and Wardle, D. A.: The ratio of Gram-positive to Gram-negative bacterial PLFA markers as an indicator of carbon availability in organic soils, Soil Biol. Biochem., 128, 111–114, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.10.010, 2019.

Feng, X., Simpson, A. J., Wilson, K. P., Dudley Williams, D., and Simpson, M. J.: Increased cuticular carbon sequestration and lignin oxidation in response to soil warming, Nat. Geosci., 1, 836–839, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo361, 2008.

Feng, X., Xu, Y., Jaffé, R., Schlesinger, W. H., and Simpson, M. J.: Turnover rates of hydrolysable aliphatic lipids in Duke Forest soils determined by compound specific 13C isotopic analysis, Org. Geochem., 41, 573–579, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2010.02.013, 2010.

Fierer, N., Schimel, J. P., and Holden, P. A.: Variations in microbial community composition through two soil depth profiles, Soil Biol. Biochem., 35, 167–176, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0038-0717(02)00251-1, 2003.

Fontaine, S., Barot, S., Barré, P., Bdioui, N., Mary, B., and Rumpel, C.: Stability of organic carbon in deep soil layers controlled by fresh carbon supply, Nature, 450, 277–280, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06275, 2007.

Franke, R., Briesen, I., Wojciechowski, T., Faust, A., Yephremov, A., Nawrath, C., and Schreiber, L.: Apoplastic polyesters in Arabidopsis surface tissues – A typical suberin and a particular cutin, Phytochemistry, 66, 2643–2658, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.09.027, 2005.

Goodfellow, M. and Williams, S. T.: Ecology of actinomycetes, Annu. Rev. Microbiol., 37, 189–216, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.mi.37.100183.001201, 1983.

Graça, J.: Suberin: The biopolyester at the frontier of plants, Front. Chem., 3, https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2015.00062, 2015.

Gunina, A., Dippold, M. A., Glaser, B., and Kuzyakov, Y.: Fate of low molecular weight organic substances in an arable soil: From microbial uptake to utilisation and stabilisation, Soil Biol. Biochem., 77, 304–313, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.06.029, 2014.

Harwood, J. L. and Russell, N. J.: Lipids in Plants and Microbes, Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-5989-0, 1984.

Hicks Pries, C. E., Castanha, C., Porras, R. C., and Torn, M. S.: The whole-soil carbon flux in response to warming, Science, 355, 1420–1423, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal1319, 2017.

Hicks Pries, C. E., Sulman, B. N., West, C., O'Neill, C., Poppleton, E., Porras, R. C., Castanha, C., Zhu, B., Wiedemeier, D. B., and Torn, M. S.: Root litter decomposition slows with soil depth, Soil Biol. Biochem., 125, 103–114, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.07.002, 2018.

Huf, S., Krügener, S., Hirth, T., Rupp, S., and Zibek, S.: Biotechnological synthesis of long-chain dicarboxylic acids as building blocks for polymers, Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Tech., 113, 548–561, https://doi.org/10.1002/ejlt.201000112, 2011.

IPCC: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis, in: Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/WG1AR5_TS_FINAL.pdf (last access: 22 January 2022), 2013.

IUSS Working Group WRB: World Reference Base for Soil Resources, International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps, 4th edn., International Union of Soil Sciences (IUSS), Vienna, Austria, 2022.

Jackson, R. B., Lajtha, K., Crow, S. E., Hugelius, G., Kramer, M. G., and Piñeiro, G.: The ecology of soil carbon: Pools, vulnerabilities, and biotic and abiotic controls, Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst., 48, 419–445, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-112414-054234, 2017.

Jansen, B. and Wiesenberg, G. L. B.: Opportunities and limitations related to the application of plant-derived lipid molecular proxies in soil science, SOIL, 3, 211–234, https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-3-211-2017, 2017.

Joergensen, R. G.: Phospholipid fatty acids in soil – Drawbacks and future prospects, Biol. Fertil. Soils, 58, 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-021-01613-w, 2022.

Kashi, H., Loeppmann, S., Herschbach, J., Schink, C., Imhof, W., Kouchaksaraee, R. M., Dippold, M. A., and Spielvogel, S.: Size matters: Biochemical mineralization and microbial incorporation of dicarboxylic acids in soil, Biogeochemistry, 162, 79–95, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-022-00990-0, 2023.

Keiluweit, M., Bougoure, J. J., Nico, P. S., Pett-Ridge, J., Weber, P. K., and Kleber, M.: Mineral protection of soil carbon counteracted by root exudates, Nat. Clim. Change, 5, 588–595, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2580, 2015.

Kim, K.-R. and Oh, D.-K.: Production of hydroxy fatty acids by microbial fatty acid-hydroxylation enzymes, Biotechnol. Adv., 31, 1473–1485, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.07.004, 2013.

Kim, S.-K. and Park, Y.-C.: Biosynthesis of ω-hydroxy fatty acids and related chemicals from natural fatty acids by recombinant Escherichia coli, Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 103, 191–199, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-018-9503-6, 2019.

Kleber, M.: What is recalcitrant soil organic matter?, Environ. Chem., 7, 320, https://doi.org/10.1071/EN10006, 2010.

Kolattukudy, P. E.: Biopolyester membranes of plants: Cutin and suberin, Science, 208, 990–1000, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.208.4447.990, 1980.

Kwatcho Kengdo, S., Peršoh, D., Schindlbacher, A., Heinzle, J., Tian, Y., Wanek, W., and Borken, W.: Long-term soil warming alters fine root dynamics and morphology, and their ectomycorrhizal fungal community in a temperate forest soil, Glob. Change Biol., 28, 3441–3458, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16155, 2022.

LaRowe, D. E. and Van Cappellen, P.: Degradation of natural organic matter: A thermodynamic analysis, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 75, 2030–2042, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2011.01.020, 2011.

Li, J., Wang, G., Mayes, M. A., Allison, S. D., Frey, S. D., Shi, Z., Hu, X., Luo, Y., and Melillo, J. M.: Reduced carbon use efficiency and increased microbial turnover with soil warming, Glob. Change Biol., 25, 900–910, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14517, 2019.

Li, L., Xu, Q., Jiang, S., Jing, X., Shen, Q., He, J.-S., Yang, Y., and Ling, N.: Asymmetric winter warming reduces microbial carbon use efficiency and growth more than symmetric year-round warming in alpine soils, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 121, e2401523121, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2401523121, 2024.

Lindahl, B. D., Ihrmark, K., Boberg, J., Trumbore, S. E., Högberg, P., Stenlid, J., and Finlay, R. D.: Spatial separation of litter decomposition and mycorrhizal nitrogen uptake in a boreal forest, New Phytol., 173, 611–620, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01936.x, 2007.

Lorenz, K., Lal, R., Preston, C. M., and Nierop, K. G. J.: Strengthening the soil organic carbon pool by increasing contributions from recalcitrant aliphatic bio(macro)molecules, Geoderma., 142, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2007.07.013, 2007.

Luo, Z., Wang, G., and Wang, E.: Global subsoil organic carbon turnover times dominantly controlled by soil properties rather than climate, Nat. Commun., 10, 3688, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11597-9, 2019.

Lützow, M. v., Kögel-Knabner, I., Ekschmitt, K., Matzner, E., Guggenberger, G., Marschner, B., and Flessa, H.: Stabilization of organic matter in temperate soils: mechanisms and their relevance under different soil conditions – A review, Eur. J. Soil Sci., 57, 426–445, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2389.2006.00809.x, 2006.

Malhotra, A., Brice, D. J., Childs, J., Graham, J. D., Hobbie, E. A., Stel, H. V., Feron, S. C., Hanson, P. J., and Iversen, C. M.: Peatland warming strongly increases fine-root growth, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 117, 17627–17634, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2003361117, 2020.

Manzoni, S., Taylor, P., Richter, A., Porporato, A., and Ågren, G. I.: Environmental and stoichiometric controls on microbial carbon-use efficiency in soils, New Phytol., 196, 79–91, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04225.x, 2012a.

Manzoni, S., Schimel, J. P., and Porporato, A.: Responses of soil microbial communities to water stress: results from a meta-analysis, Ecology, 93, 930–938, https://doi.org/10.1890/11-0026.1, 2012b.

Meier, I. C. and Leuschner, C.: Belowground drought response of European beech: fine root biomass and carbon partitioning in 14 mature stands across a precipitation gradient, Glob. Change Biol., 14, 2081–2095, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01634.x, 2008.

Melillo, J. M., Frey, S. D., DeAngelis, K. M., Werner, W. J., Bernard, M. J., Bowles, F. P., Pold, G., Knorr, M. A., and Grandy, A. S.: Long-term pattern and magnitude of soil carbon feedback to the climate system in a warming world, Science, 358, 101–105, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aan2874, 2017.

Mendez-Millan, M., Dignac, M.-F., Rumpel, C., and Derenne, S.: Can cutin and suberin biomarkers be used to trace shoot and root-derived organic matter? A molecular and isotopic approach, Biogeochemistry, 106, 23–38, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-010-9407-8, 2011.

Mueller, K. E., Polissar, P. J., Oleksyn, J., and Freeman, K. H.: Differentiating temperate tree species and their organs using lipid biomarkers in leaves, roots and soil, Org. Geochem., 52, 130–141, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2012.08.014, 2012.

Naylor, D., McClure, R., and Jansson, J.: Trends in microbial community composition and function by soil depth, Microorganisms, 10, 540, https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10030540, 2022.

Ofiti, N. O. E., Zosso, C. U., Soong, J. L., Solly, E. F., Torn, M. S., Wiesenberg, G. L. B., and Schmidt, M. W. I.: Warming promotes loss of subsoil carbon through accelerated degradation of plant-derived organic matter, Soil Biol. Biochem., 156, 108185, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2021.108185, 2021.

Ofiti, N. O. E., Schmidt, M. W. I., Abiven, S., Hanson, P. J., Iversen, C. M., Wilson, R. M., Kostka, J. E., Wiesenberg, G. L. B., and Malhotra, A.: Climate warming and elevated CO2 alter peatland soil carbon sources and stability, Nat. Commun., 14, 7533, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-43410-z, 2023.

Olson, J. S.: Energy storage and the balance of producers and decomposers in ecological systems, Ecology, 44, 322–331, https://doi.org/10.2307/1932179, 1963.

Parts, K., Tedersoo, L., Schindlbacher, A., Sigurdsson, B. D., Leblans, N. I. W., Oddsdóttir, E. S., Borken, W., and Ostonen, I.: Acclimation of fine root systems to soil warming: Comparison of an experimental setup and a natural soil temperature gradient, Ecosystems, 22, 457–472, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-018-0280-y, 2019.

Pegoraro, E. F., Zosso, C. U., Wiesenberg, G. L. B., Castanha, C., Hicks Pries, C. E., Porras, R., Soong, J. L., Schmidt, M. W. I., and Torn, M.: Depth-dependent microbial response to simulated increased root growth, SSRN [preprint], https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5006430, 2024.

Pei, J., Li, J., Luo, Y., Rillig, M. C., Smith, P., Gao, W., Li, B., Fang, C., and Nie, M.: Patterns and drivers of soil microbial carbon use efficiency across soil depths in forest ecosystems, Nat. Commun., 16, 5218, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60594-8, 2025.

Pinheiro, J., Bates, D., DebRoy, S., Sarkar, D., EISPACK authors, Heisterkamp, S., Van Willigen, B., Ranke, J., and R Core Team: nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models, R package version 3.1-166, CRAN, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme (last access: 22 August 2025), 2024.

Pisani, O., Frey, S. D., Simpson, A. J., and Simpson, M. J.: Soil warming and nitrogen deposition alter soil organic matter composition at the molecular-level, Biogeochemistry, 123, 391–409, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-015-0073-8, 2015.

Posit team: RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R, version 2024.12.1.563, Posit Software, PBC, Boston, MA, https://posit.co (last access: 8 October 2025), 2025.

Rasse, D. P., Rumpel, C., and Dignac, M.-F.: Is soil carbon mostly root carbon? Mechanisms for a specific stabilisation, Plant Soil, 269, 341–356, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-004-0907-y, 2005.

R Core Team: R: A language and environment for statistical computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, https://www.R-project.org/ (last access: 22 August 2025), 2024.

Rumpel, C. and Kögel-Knabner, I.: Deep soil organic matter – A key but poorly understood component of terrestrial C cycle, Plant Soil, 338, 143–158, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-010-0391-5, 2011.

Rumpel, C., Chabbi, A., and Marschner, B.: Carbon Storage and Sequestration in Subsoil Horizons: Knowledge, Gaps and Potentials, in: Recarbonization of the Biosphere: Ecosystems and the Global Carbon Cycle, edited by: Lal, R., Lorenz, K., Hüttl, R. F., Schneider, B. U., and von Braun, J., Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 445–464, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4159-1_20, 2012.

Scharlemann, J. P., Tanner, E. V., Hiederer, R., and Kapos, V.: Global soil carbon: Understanding and managing the largest terrestrial carbon pool, Carbon Manage., 5, 81–91, https://doi.org/10.4155/cmt.13.77, 2014.

Schenk, H. J. and Jackson, R. B.: Mapping the global distribution of deep roots in relation to climate and soil characteristics, Geoderma, 126, 129–140, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2004.11.018, 2005.