the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Soil carbon accrual and biopore formation across a plant diversity gradient

Maik Geers-Lucas

G. Philip Robertson

Alexandra N. Kravchenko

Plant diversity promotes soil organic carbon (SOC) gains through intricate changes in root-soil interactions and their subsequent influence on soil physical and biological processes. We assessed SOC and pore characteristics of soils under a range of switchgrass-based plant systems 12 years after their establishment. The systems represented a gradient of plant diversity with species richness ranging from 1 to 30 species. We focused on soil biopores as indicators of the legacy of root activity and explored biopore relationships with SOC accumulation. Biopores were measured using X-ray computed micro-tomography.

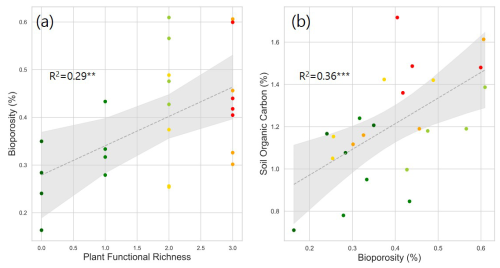

Plant functional richness explained 29 % of bioporosity and 36 % of SOC variation, while bioporosity itself explained 36 % of the variation in SOC. The most diverse plant system (30 species) had the highest SOC, while long-term bare soil fallow and monoculture switchgrass had the lowest. Of particular note was a 2-species mixture of switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) and ryegrass (Elymus canadensis), which exhibited the highest bioporosity and achieved SOC levels comparable to those of the systems with 6 and 10 plant species, and were inferior only to the system with 30 species. We conclude that plant diversity may enhance SOC through biopore-mediated mechanisms and suggest a potential for identifying specific plant combinations that may be particularly efficient for fostering biopore formation and, subsequently, SOC sequestration.

- Article

(1396 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(691 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Plant diversity has been found to positively influence soil organic carbon (SOC) accumulation in various ecosystems, including grasslands (Lange et al., 2015; Sprunger and Robertson, 2018) and row crop agriculture (Liebman et al., 2013; McDaniel et al., 2014). Among the mechanisms through which higher plant diversity promotes SOC storage are (i) high biomass and C inputs from roots (Yang and Tilman, 2020), (ii) slower root decomposition in high diversity systems due to increased root C:N ratios (Chen et al., 2017), and (iii) higher microbial activity enhanced by belowground inputs, where greater quantities of plant-added C are transformed into microbial biomass (Prommer et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2023) and then necromass (Qian et al., 2023; Mou et al., 2024). This microbially-processed C is then protected through physico-chemical associations with soil minerals (Cotrufo et al., 2022).

The quantity and chemical composition of C inputs from plant roots and soil biota play an important role in ensuring SOC gains (Berhongaray et al., 2019; Lehmann et al., 2020; Eisenhauer et al., 2017). For instance, extensive root growth and earthworm activity can facilitate the root exudates and earthworm secretions, which in turn stimulate microbial growth, C assimilation (Kuzyakov and Blagodatskaya, 2015), and the accumulation of microbial necromass (Banfield et al., 2018). Yet, the specific locations within the soil matrix where such inputs are added and their spatial distribution patterns can be an important driver in formation of SOC and its subsequent protection (Quigley and Kravchenko, 2022). In diverse plant communities, belowground competition among plants with contrasting root architectures can lead to greater root proliferation through the soil matrix, thereby increasing the density and spatial distribution of root channels that are in direct contact with the soil matrix (Gersani et al., 2001; Bargaz et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017). Similarly, diverse plant communities exhibit increased activity of soil mesofauna such as earthworms, whereby earthworms create new biogenic channels that expand the contact surface between soil and organic inputs (Milcu et al., 2008; Kuzyakov and Kooch, 2024). The redistribution of these soil–organic matter interfaces varies considerably with plant diversity and species composition (Marshall et al., 2016; Zahorec et al., 2022). For instance, shifts in root morphology and spatial distribution in response to neighboring plant species (Bolte and Villanueva, 2006; Wang et al., 2014) indicate that the formation of root-derived channels and the localization of C storage depend on community composition. Likewise, findings that earthworm activity differs according to the presence of legumes (Eisenhauer et al., 2009) suggest that both the quantity and spatial pattern of SOC storage depend on plant species identity and diversity.

Analysis of root-soil and mesofauna-soil interactions in diverse perennial plant communities in situ is extremely challenging due to the opaque nature of soil and the difficulty of carrying out long-term (e.g., multiyear) continuous rhizobox or greenhouse studies. Thus, much knowledge is based on speculations from the data on root volumes and architecture generated upon disturbing the system to procure the roots and upon conducting the root measurements after cleaning away the soil (Lange et al., 2015). Likewise, earthworm–soil interactions have often been examined by simple comparisons between earthworm activity and soil carbon, while only a few studies have employed the technically demanding approach of artificially creating earthworm biopores with spatial information (Hoang et al., 2016). In contrast, sampling intact soil from long-term field studies and visualizing root residues, particulate organic matter (POM), and pores via X-ray computed micro-tomography (μ CT) can generate helpful information on root-soil and earthworm-soil interactions (Helliwell et al., 2013). This is where identification and quantification of biopores can be particularly advantageous, because it allows capturing the legacy of root and mesofauna proliferation through the soil matrix and estimating the volume of the soil matrix that has received their C inputs in the past.

Biopores are the soil pores originated from biological activity such as plant root growth and the movement of earthworms and other soil fauna (Dexter, 1986; Blackwell et al., 1990). Biopores act as preferential pathways for root growth, organic matter inputs, water, and nutrient flow, thereby creating microenvironments that favor microbial colonization and necromass accumulation (Guhra et al., 2022; Kautz, 2015; Wendel et al., 2022). Root-originated biopores, formed either by growth of living roots or by decomposition of old roots, are particularly significant as they are 40 times more abundant, especially in subsoils, compared to earthworm biopores (Banfield et al., 2018). Root biopores are tubular, round-shaped channels with sizes ranging from a few micron to several centimeters (Kautz, 2015). Since root inputs are primarily introduced into the soil through the biopores, they have > 2.5 times higher soil C contents compared to bulk soil (Banfield et al., 2017). Rapid microbial decomposition of plant residues and accumulation of microbial residues observed in root biopores (Banfield et al., 2018) suggest that root biopore characteristics may reflect the physical preferences and biochemical processes involved in the transformation and accumulation of plant-derived C.

Reuse of existing biopores by newly grown roots is a commonly observed process in annual crops such as wheat, fodder radish, and spring barley (White and Kirkegaard, 2010; Wahlström et al., 2021). Switchgrass, a North American prairie grass, currently actively explored as a potential bioenergy feedstock (Larnaudie et al., 2022; Zegada-Lizarazu et al., 2022), is known for its particularly active use of old root channels (i.e., biopore reuse), especially when grown in monoculture (Lucas et al., 2023). Because of their continuous reuse, accompanied by repeated influxes of new C and stimulated microbiota, biopores in perennial plant systems can be viewed as hotspots of C processing and are both a product of historic root-soil interactions and a current arena of such interactions (Mueller et al., 2024). Taken together, these considerations suggest that the morphology and spatial pattern of root biopores may serve as an informative indicator of root-derived SOC within the soil matrix.

We posit that biopore information derived from X-ray μ CT is particularly informative for assessing root impacts and root–soil interactions in perennial plant systems. In species-rich perennial communities, interspecific interactions generate complex root architectures and heterogeneous rooting pathways, which in turn produce spatially variable inputs of root-derived SOC (Zahorec et al., 2022). In this context, increased root-originated biopores (e.g., the volume fraction and connectivity) can indicate diversified root growth paths and intensified root–soil contact in perennial systems. Accoringly, we hypothesize that higher plant diversity promotes the abundance and formation of root biopores and that this enhanced biopore development is associated with greater gains in SOC. Specifically, our objectives are to examine (i) how a plant-diversity gradient shapes soil-pore characteristics, with emphasis on biopores, and (ii) whether the (bio)pore abundance is associated with SOC levels accrued over the preceding 12 years.

2.1 Experimental site and soil sampling

Soil samples were collected from the Cellulosic Biofuel Diversity Experiment site established in 2008 at Kellogg Biological Station (KBS, 42°23′47′′ N, 85°22′26′′ W), a part of the KBS Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) program (Robertson and Hamilton, 2015). The soil is fine-loamy, mixed, mesic, Typic Hapludalf (Kalamazoo loam). The experiment consists of twelve plant systems representing a 12-point gradient of plant diversity (CE1-CE12), 6 of which were used in this study. Specifically, we sampled a bare soil system, which was kept free of vegetation since 2016 after 8 years of continuous corn (CE1), a monoculture switchgrass (Panicum virgatum, L.; var. Southlow) system (CE7), a mixture of two grass species, namely, switchgrass and Canadian rye (Elymus canadensis L.) (CE8), a mixture of 6 native grasses (CE9), a mixture of 6 native grasses and four forbs (CE10), and a mixture of 6 native grasses and 24 forbs (CE12). Plant species of each system are listed in Table S1 in the Supplement. The experiment is in a randomized complete block design with four replicated 9.1 m × 27.4 m plots for each plant system (https://lter.kbs.msu.edu/research/long-term-experiments/cellulosic-biofuels-experiment/, last access: 2 December 2025).

For soil pore analysis, intact soil cores (5 cm diameter (Ø) and 5 cm height) were taken from the 7–12 cm depth interval in July 2019. This depth encompasses the zone of greatest fine-root abundance and turnover, where root-derived C inputs and microbial activity are most pronounced (Halli et al., 2022; Roosendaal et al., 2016). Loose soil adjacent to each core was also procured for measurements of other soil characteristics. Two soil cores were collected from each plot, for a total of 48 soil cores (6 systems × 4 replicate plots × 2 cores per plot).

Aboveground biomass was measured each autumn (October–November) from 2010 to 2019 in all plots except CE1 (bare soil) (Fig. S1a in the Supplement). For the present analysis, we used the 2018 and 2019 biomass datasets (Fig. S1b). Soil sampling for this study occurred in July 2019; thus, the 2019 fall biomass provides the most temporally proximate estimate of aboveground production for the soils analyzed, while the 2018 biomass offers the preceding-year context and helps mitigate interannual variability. The entire aboveground biomass from each plot was harvested with a mini combine, leaving 10–15 cm of stubble, and weighed and subsampled for moisture content determination. Due to destructive and intensive sampling required for belowground biomass quantification, such measurements could not be undertaken. Therefore, all plant biomass estimates in this study are explicitly based on aboveground components only.

2.2 Soil characteristics measured using destructively sampled soil

Soil moisture at the time of core sampling was determined gravimetrically using a 20 g subsample of loose soil immediately upon collection. The remaining loose soil samples were air-dried for 2 d and sieved to < 2 mm for further analysis.

SOC and total soil N were measured by combustion analysis using an elemental CN analyzer (Costech Analytical Technologies Inc., CA, USA). SOC mineralization was measured via 10 d incubation: 10 g of air-dried soil were brought to 20 % gravimetric moisture, placed in a beaker that was then placed in a 450 mL Mason jar with ∼ 5 mL of purified water on the bottom for maintaining high humidity within the jar. Mason jars were kept in the dark at 20 °C for 10 d, and CO2 concentration in the headspace was measured for each jar using Infrared Photoacoustic Spectroscopy (INNOVA Air Tech Instruments, Denmark).

2.3 Soil core scanning and pore structure analysis

Soil cores were subjected to X-ray computed micro-tomography (North Star Imaging, X3000, Rogers, USA) to visualize and quantify soil pore structure. X-ray μ CT is particularly suitable for biopore investigation (Wendel et al., 2022), enabling the examination of accumulated evidence of past root-soil interactions (Helliwell et al., 2013). The scanning was conducted with a projection energy level of 75 KV and 450 µA, with 2880 projections per scan. 3D reconstruction of the images was computed using efX-CT software (North Star Imaging, Rogers, USA) obtaining a final scanning resolution of 18.2 µm. Reconstructed images were processed using Fiji software (Schindelin et al., 2012) and simpleITK package in Python (Beare et al., 2018). A series of image pre-processing steps was conducted using Fiji and its Xlib plugin (Münch and Holzer, 2008). Specifically, images were cropped into 1500 pixel × 1500 pixel with a height of 2240 pixels to remove artifacts near core edges. Then, a 2D non-local filter (sigma = 0.1) was applied to reduce noise.

For pore segmentation, threshold values were obtained from eight segmentation methods, i.e., Otsu, Kitler, Huang, Triangle, ISO, Li, Renyi, and Moments. Outliers that exceeded > 1 standard deviation of the mean were removed. This approach enabled us to minimize the side effects of using one specific thresholding method and ensured robustness of the segmentation (Schlüter et al., 2014). Hereafter, we refer to the > 18.2 µm Ø pores as visible pores, and their total volume as visible porosity. Pore size distributions of visible pores were determined by the Local Thickness method embedded in Fiji, which is based on maximal inscribed spheres approach (Silin and Patzek, 2006). For biopore identification, the images were subjected to Tubeness filtering in Fiji to detect tubular type pores of different radius. Detailed procedures for biopore segmentation are publicly available (https://github.com/Maik-Lu/Roots_and_Biopores, last access: 2 December 2025) (Lucas et al., 2022). Total volumes of visible pores and biopores were presented as visible porosity and bioporosity. Surface area of biopores was calculated by applying assumption that the biopore shape is cylindrical in a given radius, and the mean distance of soil matrix to biopores was calculated using the Euclidean Distance Transform (3D) function in Fiji (Lucas et al., 2025).

2.4 Plant diversity indicators

Two plant diversity indicators were used in this study: (i) plant species richness, and (ii) plant functional richness (Díaz and Cabido, 2001). Plant species richness was represented by the number of plant species in each treatment, i.e., 0, 1, 2, 6, 10, and 30 for CE1, CE7, CE8, CE9, CE10, and CE12, respectively. For plant functional richness we adopted the ecological concept of plant functional types, used to simplify plant diversity and behavior in ecological models (McMahon et al., 2011). Specifically, we followed the approach used in grassland studies (Mangan et al., 2011; Spiesman et al., 2018; Tilman et al., 2006) by separating species based on different photosynthetic pathways (C3 vs. C4), and leaf shape (broad-leaf vs. grasses) to form three functional groups, namely, C3 grasses, C4 grasses, and forbs. Based on species characteristics (Table S1), plant functional richness of each treatment was equal to 0, 1, 2, 2, 3, and 3 for CE1, CE7, CE8, CE9, CE10, and CE12, respectively.

2.5 Statistical analysis

The statistical model for SOC, total soil N, C:N ratio, 10 d mineralization, visible porosity, and bioporosity data consisted of plant system as a fixed effect, and experimental blocks and blocks by systems interaction as random effects (Milliken and Johnson, 2009). The latter term, in essence, represents experimental plots and was used as an error term to test the plant system effect. The statistical model for the aboveground biomass measured during 2 consecutive years further included year and its interaction with the plant system as fixed factors. The statistical model for pore and biopore size distribution data included the pore size class and its interaction with plant system as fixed effects, and soil core nested within the plant system and experimental plot as the random effect. When the ANOVA was significant, all pairwise mean comparisons among plant systems were conducted within each pore size class. Normality was checked by visual inspection of normal probability plots, and when found violated, the data were subjected to either square root or lognormal transformation prior to the analyses. The equal variance assumption was tested by Levene's test, and when found to be violated, the unequal variance model was fitted using the approach suggested by Milliken and Johnson (2009).

To explore associations of soil characteristics with pore and biopore data, the porosity and bioporosity from two intact cores of each plot were averaged, followed by linear regression analysis. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 software, using PROC MIXED and PROC REG procedure. Results are reported as statistically significant at p < 0.05 and as trends at p < 0.1. P-values < 0.1, < 0.05, and < 0.01 are marked with ∗, , and , respectively.

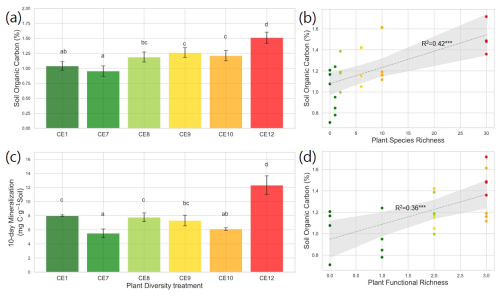

Figure 1Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) content (a) and 10 d mineralization (c) in the studied plant diversity systems (CE1: Bare soil, CE7: Switchgrass, CE8: Switchgrass + Rye, CE9: 6 grasses, CE10: 6 grasses + 4 forbs. CE12: 6 grasses + 10 forbs). Correlations between SOC and Plant Species Richness (b), as well as Plant Functional Richness (d), are shown. Error bars in (a) and (c) show standard error of the mean. Letters indicate significant differences among plant diversity treatments (p < 0.05). Dotted gray lines in (b) and (d) represent fitted regression models, with light gray shaded area denoting 95 % confidence interval. R2 values are provided for each model. Asterisks () indicate statistically significant regression models at p < 0.01.

3.1 Plant biomass and SOC characteristics of the studied plant systems

Total aboveground biomass (2018–2019) tended to be higher in the most diverse systems (CE10 and CE12) than in grass-only systems (CE8 and CE9), while the monoculture switchgrass (CE7) was intermediate (p < 0.10, Fig. S1b). Total aboveground biomass was weakly correlated with plant species richness (Fig. S2a in the Supplement) and not correlated with plant functional richness (Fig. S2b). Total aboveground biomass was not correlated with SOC contents (Fig. S2c). The plant systems with the highest diversity (CE12) had markedly higher SOC as compared to the rest of the systems (Fig. 1a). However, an increase in plant diversity from a 2-species (CE8) to 6-species (CE9) and then to a 10-species (CE10) system did not affect SOC (Fig. 1a). Soil C:N ratio was smallest in monoculture switchgrass (CE7), and greatest in high diversity systems (CE10 and CE12) (p < 0.01, Fig. S3 in the Supplement). C mineralization was highest in CE12, followed by bare soil (CE1), and CE8 (Fig. 1c). C mineralization was lowest in CE7 and CE10.

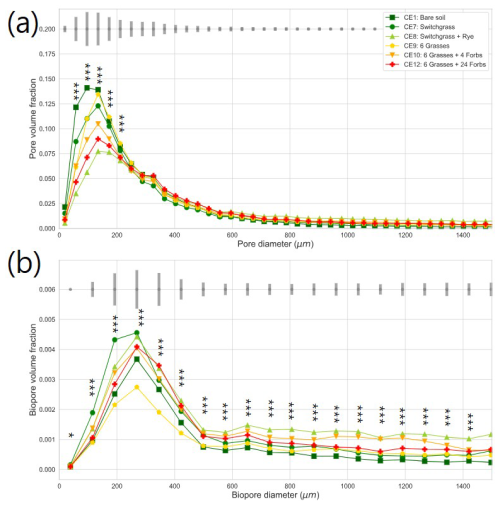

Figure 2Pore size distribution (a) and biopore size distribution (b) in the studied plant diversity systems (CE1: Bare soil, CE7: Switchgrass, CE8: Switchgrass + Rye, CE9: 6 grasses, CE10: 6 grasses + 4 forbs. CE12: 6 grasses + 10 forbs). Gray bars indicate the least significant difference (LSD) in each (Bio)pore diameter group. Asterisks and ∗ mark significant differences among the plant diversity treatments at each (Bio)pore diameter at p < 0.01 and p < 0.10 significance.

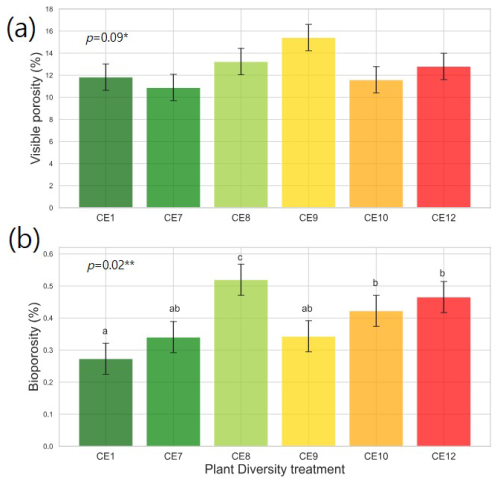

Figure 3Visible porosity (a) and bioporosity (b) in the studied plant diversity systems (CE1: Bare soil, CE7: Switchgrass, CE8: Switchgrass + Rye, CE9: 6 grasses, CE10: 6 grasses + 4 forbs. CE12: 6 grasses + 10 forbs). Error bars show standard error of the mean. Asterisks ∗ and indicate statistically significant differences among plant diversity treatments at p < 0.10 and 0.05, respectively. Letters indicate significant differences among plant diversity treatments (p < 0.05).

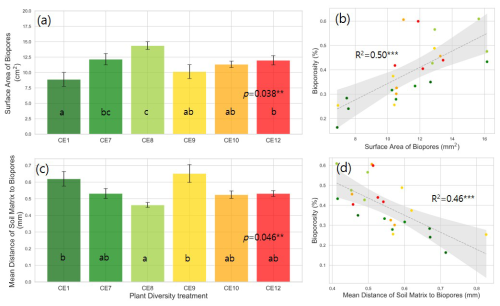

Figure 4Surface area of biopores (a) and mean distance of soil matrix to biopores (c) in the studied plant diversity systems (CE1: Bare soil, CE7: Switchgrass, CE8: Switchgrass + Rye, CE9: 6 grasses, CE10: 6 grasses + 4 forbs. CE12: 6 grasses + 10 forbs). Error bars in (a) and (c) show standard error of the mean. Correlations between bioporosity and surface area of biopores (b), as well as mean distance of soil matrix to biopores (d), are shown. Letters indicate significant differences among plant diversity treatments (p < 0.05). Dotted gray lines in (b) and (d) represent fitted regression models, with light gray shaded area denoting 95 % confidence interval. R2 values are provided for each model. Asterisks () indicate statistically significant regression models at p < 0.01.

3.2 Biopore characteristics

Plant systems affected pore size distributions (Fig. 2a), where CE8, CE10, and CE12 had the lowest volumes of < 200 µm diameter pores and the highest volumes of > 400 µm diameter pores, while an opposite trend was observed for CE1, CE7, and CE9 systems. Biopores, which was segmented based on its tubular morphology, tended to be larger than regular pores of arbitrary shapes (Fig. 2). For example, while the mode (i.e., the most frequent value) pore diameter of the entire pore size distribution was ∼ 100 µm (Fig. 2a), for biopores the modal pore diamater was ∼ 300 µm (Fig. 2b). Visible porosity (pores of > 18.2 µm diam.) was highest in CE9 followed by CE8 (Fig. 3a). In contrast to visible porosity, bioporosity was the highest in CE8, which is comprised of switchgrass and Canadian ryegrass (Fig. 3b). In addition to CE8, throughout the entire range of biopore sizes, CE10 and CE12 also had consistently higher biopore volumes (Fig. 2b) as well as higher total bioporosity than the rest of the systems (Fig. 3b). Total surface areas of biopores (all pores of < 1500 µm diam.) were highest in CE7 and CE8, and lowest in CE1 (p < 0.05, Fig. 4a). Mean distance of soil matrix to biopores showed an opposite trend from surface area, i.e., farthest in CE1 and CE9 and shortest in CE8 (p < 0.05, Fig. 4d).

Figure 5Correlation between plant functional richness and bioporosity (a), and between bioporosity and SOC (b). R2 values are provided for each model. Dotted gray lines represent fitted regression models, with light gray shaded area denoting 95 % confidence interval. Asterisks and indicate statistically significant regression models at p < 0.05 and 0.01, respectively.

3.3 Correlation between plant diversity, pore characteristics, and SOC

Plant species richness and plant functional richness were both positively associated with SOC, with species richness explaining 42 % of the variance in SOC (p < 0.01; Fig. 1b) and functional richness explaining 36 % (p < 0.01; Fig. 1d). Within the pore metrics, biopore surface area was positively related to bioporosity (R2 = 0.50, p < 0.01; Fig. 4b), whereas the mean distance from the soil matrix to the nearest biopore was negatively related to bioporosity (R2 = 0.46, p < 0.01; Fig. 4d). Bioporosity increased with plant diversity. Species richness explained 10 % of the variance in bioporosity (p < 0.01; Fig. S4a in the Supplement), and functional richness explained 29 % (p < 0.05; Fig. 5a). Consistent with these patterns, bioporosity was positively correlated with SOC (R2 = 0.36, p < 0.01; Fig. 5b).

4.1 Biopores link plant diversity and SOC accumulation

Consistent with our expectations and previous literature (Lange et al., 2015; Prommer et al., 2020; Yang and Tilman, 2020), 12 years of contrasting vegetation was sufficient to develop differences in SOC among the studied plant systems, with the highest SOC observed in the soil under the most diverse plant community (Fig. 1a, b, and d). However, the lack of correlation between the plant aboveground biomass and SOC observed here (Fig. S2c) suggests that greater plant biomass did not itself significantly contribute to SOC increases. This lack of impact is even more obvious when comparing CE7 (monoculture) and CE8 (2-species system), where CE8 had the lowest aboveground biomass but its SOC was comparable to that from the systems with 3–5 times higher plant species richness and higher aboveground biomass (CE9 and 10, Figs. 1a and S1b).

The positive association between SOC and bioporosity was another result consistent with our expectations (Fig. 5b). The correlation between plant richness and SOC was largely driven by the highest species richness of 30, which was a high leverage point in our regression analysis (Fig. 1b and d). Thus, even though the R2 for bioporosity-SOC regression was lower than that from species richness-SOC (0.36 vs. 0.42), bioporosity could be viewed as a better predictor of SOC. Moreover, the CE8 system with its unexpectedly high SOC turned out to have higher bioporosity and higher volumes of biopores of all sizes than the other studied systems (Figs. 2b and 3b). This observation is consistent with previous reports identifying biopores as sites of high inputs of labile substrates (Pierret et al., 1999; Xiong et al., 2022), increased microbial abundance and activity (Wendel et al., 2022), and enhanced necromass accumulation (Banfield et al., 2018), all of which highlight the role of biopores in contributing to SOC accrual. It should be noted that belowground biomass was not directly measured in this study, which may have influenced estimates of biopore-related parameters. Direct belowground measurements would allow disentangling root-biomass–driven biopore formation from species-interaction effects, and would further clarify the contribution of belowground biomass to SOC accrual and the independent role of biopores.

The biopores in CE8 had the greatest surface area, followed by the most diverse system (Fig. 4a). The mean distance of soil matrix to biopores was the shortest in CE8, followed by diverse systems (CE10 and CE12) (Fig. 4c). The surface area of biopores is critical as it represents the specific portion of the soil matrix that directly intercepts root-derived C inputs, i.e., rhizodeposits (Keller et al., 2021) and decomposed root residues processed by soil microbes (Kim et al., 2022). A shorter mean distance from soil matrix to biopores indicates that root-derived C was accessible to a large community of soil microorganisms, probably facilitating efficient transfer and sequestration of microbially processed C into the soil matrix (Kravchenko et al., 2019). These findings emphasize the currently underestimated importance of formation, abundance, and surface properties of biopores in affecting soil biochemical status, specifically, influencing plant-derived inputs and their potential protection within the soil matrix. Our study suggests that this role might be particularly pronounced in ecosystems with high plant species diversity.

Our C mineralization results (Fig. 1c) did not much correspond with previous reports indicating that higher plant diversity enhances microbial C use efficiency (Eisenhauer et al., 2009), likely driven by greater chemical heterogeneity and enhanced substrate accessibility to soil microbes (Mellado-Vázquez et al., 2016; Domeignoz-Horta et al., 2014). We suggest that future studies incorporate more detailed assessments of microbial biomass, community composition, and diversity to better elucidate carbon processes occurring in biopores. These inconsistencies highlight the need for further investigation of microbial activities and net C balance to identify the specific microbial pathways operating in biopores. In particular, the integration of X-ray μ CT with pore-scale microbial analyses, as recently demonstrated by Li et al. (2024), represents a promising approach to advance our understanding of SOC accumulation mediated by soil microorganisms in biopores structures.

4.2 Future research directions: winning plant species combinations?

Interestingly, while bioporosity was not affected by the number of plant species within the system, it was positively correlated with the systems' functional diversity (Figure 5a). This implies that greater diversity of functional groups – rather than a greater diversity of plant species per se – may lead to a more thorough exploration of the soil matrix in part through biopore formation, subsequently enhancing SOC accumulation. Moreover, our results suggest that certain combinations of plant species, e.g., CE8 (Switchgrass + Canadian rye) in this study, can be more “effective” in building biopores, and potentially furthering SOC accumulation through rapid processing of added substrates (Banfield et al., 2017; Banfield et al., 2018). We hypothesize that Canadian rye could be viewed as a species with a keystone effect on bioporosity and SOC accumulation.

A “keystone effect” refers to beneficial effect of a certain plant species on ecosystem function (Mills et al., 1993). For instance, legume species added to grasslands have been found to disproportionately affect biomass productivity and root C accrual (Minns et al., 2001; Fornara and Tilman, 2008; Lange et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2019) due to N assimilation by legumes and consequent utilization of that N by grasses (Minns et al., 2001; Mangan et al., 2011; Mou et al., 2024). Introduction of a C3 plant, i.e., Canadian rye, into a monoculture C4 switchgrass community may have altered switchgrass root growth and exudation patterns. This conjecture is supported by a report on sensitivity of chemical composition of switchgrass root exudates to neighbouring plant species (e.g., C3 Koeleria macrantha Ledeb.), with subsequent increases in microbial biomass C and changes in bacterial diversity in the switchgrass rhizosphere (Ulbrich et al., 2022). We see the need for further investigation into the role that individual members of grassland communities may play in stimulating soil pore structure development and SOC accumulation. Identifying keystone species enabling more efficient C accumulation can guide plant restoration and SOC accrual efforts.

The 12 year grassland experiment demonstrates that SOC accumulation is governed by plant diversity, with the benefits of high plant diversity being, in part, exhibited via development of biopores. Yet, certain species combinations may lead to biopore formation and SOC accumulation benefits disproportional to the actual level of the plant system diversity. Specifically, the 2-species mixture of C4 switchgrass and C3 Canadian rye created the greatest bioporosity, shortest mean soil-to-pore distance, and the largest biopore surface area, thereby accelerating microbial processing and stabilization of root-derived C in the surrounding matrix. These findings highlight bioporosity as a more reliable proxy for SOC gains than plant species number alone, and point to potential existence of specific “keystone” species combinations that may disproportionately enhance soil structure and C sequestration. Identifying and deploying such functionally complementary plant species can offer a targeted pathway for optimizing grassland restoration and long-term SOC storage.

All data underlying the main article are provided in the Supplement (Tables S2 and S3).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-11-1029-2025-supplement.

KK: Formal analysis, investigation, Writing-original draft, visualization. MG: Software, Validation, Writing-Review and Editing. GPR: Resources, Project administration, Writing-Review and Editing. AK: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing-Review and Editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Support for this research was provided by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research (grant no. DESC0018409), by the National Science Foundation Long-term Ecological Research Program (grant no. DEB 2224712) at the Kellogg Biological Station, 2019 Kellogg Biological Station LTER Fellowship (Awardee K. Kim), and by Michigan State University AgBioResearch. This work was also supported by the New Faculty Startup Fund from Seoul National University (project no. 0525-20240168), and by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (grant no. RS-2025-24535459).

This paper was edited by Emily Solly and reviewed by Shang Wang, Riccardo Picone, and one anonymous referee.

Banfield, C. C., Dippold, M. A., Pausch, J., Hoang, D. T., and Kuzyakov, Y.: Biopore history determines the microbial community composition in subsoil hotspots, Biology and Fertility of Soils, 53, 573–588, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-017-1201-5, 2017.

Banfield, C. C., Pausch, J., Kuzyakov, Y., and Dippold, M. A.: Microbial processing of plant residues in the subsoil–The role of biopores, Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 125, 309–318, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.08.004, 2018.

Bargaz, A., Noyce, G. L., Fulthorpe, R., Carlsson, G., Furze, J. R., Jensen, E. S., Dhiba, D., and Isaac, M. E.: Species interactions enhance root allocation, microbial diversity and P acquisition in intercropped wheat and soybean under P deficiency, Applied Soil Ecology, 120, 179–188, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2017.08.011, 2017.

Beare, R., Lowekamp, B., and Yaniv, Z.: Image segmentation, registration and characterization in R with SimpleITK, Journal of Statistical Software, 86, https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v086.i08, 2018.

Berhongaray, G., Cotrufo, F. M., Janssens, I. A., and Ceulemans, R.: Below-ground carbon inputs contribute more than above-ground inputs to soil carbon accrual in a bioenergy poplar plantation, Plant and Soil, 434, 363–378, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-018-3850-z, 2019.

Blackwell, P., Green, T., and Mason, W.: Responses of biopore channels from roots to compression by vertical stresses, Soil Science Society of America Journal, 54, 1088–1091, https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1990.03615995005400040027x, 1990.

Bolte, A. and Villanueva, I.: Interspecific competition impacts on the morphology and distribution of fine roots in European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) and Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karst.), European Journal of Forest Research, 125, 15–26, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-005-0075-5, 2006.

Chen, H., Mommer, L., Van Ruijven, J., De Kroon, H., Fischer, C., Gessler, A., Hildebrandt, A., Scherer-Lorenzen, M., Wirth, C., and Weigelt, A.: Plant species richness negatively affects root decomposition in grasslands, Journal of Ecology, 105, 209–218, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12650, 2017.

Cotrufo, M. F., Haddix, M. L., Kroeger, M. E., and Stewart, C. E.: The role of plant input physical-chemical properties, and microbial and soil chemical diversity on the formation of particulate and mineral-associated organic matter, Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 168, 108648, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2022.108648, 2022.

Dexter, A.: Model experiments on the behaviour of roots at the interface between a tilled seed-bed and a compacted sub-soil: III. Entry of pea and wheat roots into cylindrical biopores, Plant and Soil, 95, 149–161, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02378860, 1986.

Díaz, S. and Cabido, M.: Vive la différence: plant functional diversity matters to ecosystem processes, Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 16, 646–655, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02283-2, 2001.

Domeignoz-Horta, L. A., Cappelli, S. L., Shrestha, R., Gerin, S., Lohila, A. K., Heinonsalo, J., Nelson, D. B., Kahmen, A., Duan, P., and Sebag, D.: Plant diversity drives positive microbial associations in the rhizosphere enhancing carbon use efficiency in agricultural soils, Nature Communications, 15, 8065, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52449-5, 2014.

Eisenhauer, N., Milcu, A., Sabais, A. C., Bessler, H., Weigelt, A., Engels, C., and Scheu, S.: Plant community impacts on the structure of earthworm communities depend on season and change with time, Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 41, 2430–2443, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.09.001, 2009.

Eisenhauer, N., Lanoue, A., Strecker, T., Scheu, S., Steinauer, K., Thakur, M. P., and Mommer, L.: Root biomass and exudates link plant diversity with soil bacterial and fungal biomass, Scientific Reports, 7, 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44641, 2017.

Fornara, D. and Tilman, D.: Plant functional composition influences rates of soil carbon and nitrogen accumulation, Journal of Ecology, 96, 314–322, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2007.01345.x, 2008.

Gersani, M., Brown, J. S., O'Brien, E. E., Maina, G. M., and Abramsky, Z.: Tragedy of the commons as a result of root competition, Journal of Ecology, 89, 660–669, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0022-0477.2001.00609.x, 2001.

Guhra, T., Stolze, K., and Totsche, K. U.: Pathways of biogenically excreted organic matter into soil aggregates, Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 164, 108483, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2021.108483, 2022.

Halli, H. M., Govindasamy, P., Choudhary, M., Srinivasan, R., Prasad, M., Wasnik, V. K., Yadav, V., Singh, A. K., Kumar, S. , Vijay, D., and Pathak, H: Range grasses to improve soil properties, carbon sustainability, and fodder security in degraded lands of semi-arid regions, Science of The Total Environment, 851, 158211, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158211, 2022.

Helliwell, J. R., Sturrock, C. J., Grayling, K. M., Tracy, S. R., Flavel, R., Young, I., Whalley, W., and Mooney, S. J.: Applications of X-ray computed tomography for examining biophysical interactions and structural development in soil systems: a review, European Journal of Soil Science, 64, 279–297, https://doi.org/10.1111/ejss.12028, 2013.

Hoang, D. T., Pausch, J., Razavi, B. S., Kuzyakova, I., Banfield, C. C., and Kuzyakov, Y.: Hotspots of microbial activity induced by earthworm burrows, old root channels, and their combination in subsoil, Biology and Fertility of Soils, 52, 1105–1119, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-016-1148-y, 2016.

Kautz, T.: Research on subsoil biopores and their functions in organically managed soils: A review, Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 30, 318–327, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170513000549, 2015.

Keller, A. B., Brzostek, E. R., Craig, M. E., Fisher, J. B., and Phillips, R. P.: Root-derived inputs are major contributors to soil carbon in temperate forests, but vary by mycorrhizal type, Ecology Letters, 24, 626–635, https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13651, 2021.

Kim, K., Gil, J., Ostrom, N. E., Gandhi, H., Oerther, M. S., Kuzyakov, Y., Guber, A. K., and Kravchenko, A. N.: Soil pore architecture and rhizosphere legacy define N2O production in root detritusphere, Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 166, 108565, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2022.108565, 2022.

Kravchenko, A., Guber, A., Razavi, B., Koestel, J., Quigley, M., Robertson, G., and Kuzyakov, Y.: Microbial spatial footprint as a driver of soil carbon stabilization, Nature Communications, 10, 3121, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11057-4, 2019.

Kuzyakov, Y. and Blagodatskaya, E.: Microbial hotspots and hot moments in soil: concept & review, Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 83, 184–199, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.01.025, 2015.

Kuzyakov, Y. and Kooch, Y. (Eds.): Earthworm Biopores for Transport and Nutrient Cycling, in: Earthworms and Ecological Processes, Springer, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-64510-5_16, pp. 417-432, 2024.

Lange, M., Eisenhauer, N., Sierra, C. A., Bessler, H., Engels, C., Griffiths, R. I., Mellado-Vázquez, P. G., Malik, A. A., Roy, J., and Scheu, S.: Plant diversity increases soil microbial activity and soil carbon storage, Nature Communications, 6, 6707, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7707, 2015.

Larnaudie, V., Ferrari, M. D., and Lareo, C.: Switchgrass as an alternative biomass for ethanol production in a biorefinery: Perspectives on technology, economics and environmental sustainability, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 158, 112115, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2022.112115, 2022.

Lee, J. H., Lucas, M., Guber, A. K., Li, X., and Kravchenko, A. N.: Interactions among soil texture, pore structure, and labile carbon influence soil carbon gains, Geoderma, 439, 116675, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2023.116675, 2023.

Li, Z., Kravchenko, A. N., Cupples, A., Guber, A. K., Kuzyakov, Y., Philip Robertson, G., and Blagodatskaya, E.: Composition and metabolism of microbial communities in soil pores, Nature Communications, 15, 3578, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47755-x, 2024.

Lehmann, J., Hansel, C. M., Kaiser, C., Kleber, M., Maher, K., Manzoni, S., Nunan, N., Reichstein, M., Schimel, J. P., and Torn, M. S.: Persistence of soil organic carbon caused by functional complexity, Nature Geoscience, 13, 529–534, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-020-0612-3, 2020.

Liebman, M., Helmers, M. J., Schulte, L. A., and Chase, C. A.: Using biodiversity to link agricultural productivity with environmental quality: Results from three field experiments in Iowa, Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 28, 115–128, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170512000300, 2013.

Lucas, M., Nguyen, L. T., Guber, A., and Kravchenko, A. N.: Cover crop influence on pore size distribution and biopore dynamics: Enumerating root and soil faunal effects, Frontiers in Plant Science, 13, 928569, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.928569, 2022.

Lucas, M., Santiago, J. P., Chen, J., Guber, A., and Kravchenko, A.: The soil pore structure encountered by roots affects plant-derived carbon inputs and fate, New Phytologist, 240, 515–528, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.19159, 2023.

Lucas, M., Gil, J., Robertson, G., Ostrom, N., and Kravchenko, A.: Changes in soil pore structure generated by the root systems of maize, sorghum and switchgrass affect in situ N2O emissions and bacterial denitrification, Biology and Fertility of Soils, 61, 367–383, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-023-01761-1, 2025.

Mangan, M. E., Sheaffer, C., Wyse, D. L., Ehlke, N. J., and Reich, P. B.: Native perennial grassland species for bioenergy: establishment and biomass productivity, Agronomy Journal, 103, 509–519, https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2010.0360, 2011.

Marshall, A. H., Collins, R. P., Humphreys, M. W., and Scullion, J.: A new emphasis on root traits for perennial grass and legume varieties with environmental and ecological benefits, Food and Energy Security, 5, 26–39, https://doi.org/10.1002/fes3.78, 2016.

McDaniel, M. D., Tiemann, L. K., and Grandy, A. S.: Does agricultural crop diversity enhance soil microbial biomass and organic matter dynamics? A meta-analysis, Ecological Applications, 24, 560–570, https://doi.org/10.1890/13-0616.1, 2014.

McMahon, S. M., Harrison, S. P., Armbruster, W. S., Bartlein, P. J., Beale, C. M., Edwards, M. E., Kattge, J., Midgley, G., Morin, X., and Prentice, I. C.: Improving assessment and modelling of climate change impacts on global terrestrial biodiversity, Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 26, 249–259, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2011.02.012, 2011.

Mellado-Vázquez, P. G., Lange, M., Bachmann, D., Gockele, A., Karlowsky, S., Milcu, A., Piel, C., Roscher, C., Roy, J., and Gleixner, G.: Plant diversity generates enhanced soil microbial access to recently photosynthesized carbon in the rhizosphere, Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 94, 122–132, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.11.012, 2016.

Milcu, A., Partsch, S., Scherber, C., Weisser, W. W., and Scheu, S.: Earthworms and legumes control litter decomposition in a plant diversity gradient, Ecology, 89, 1872–1882, https://doi.org/10.1890/07-1377.1, 2008.

Milliken, G. A. and Johnson, D. E.: Analysis of Messy Data Volume 1, Chapman and Hall/CRC, USA, https://doi.org/10.1201/EBK1584883340, 2009.

Mills, L. S., Soulé, M. E., and Doak, D. F.: The keystone-species concept in ecology and conservation, BioScience, 43, 219–224, https://doi.org/10.2307/1312122, 1993.

Minns, A., Finn, J., Hector, A., Caldeira, M., Joshi, J., Palmborg, C., Schmid, B., Scherer-Lorenzen, M., Spehn, E., Troumbis, A., and BIODEPTH project: The functioning of European grassland ecosystems: potential benefits of biodiversity to agriculture, Outlook on Agriculture, 30, 179–185, https://doi.org/10.5367/000000001101293634, 2001.

Mou, X., Lv, P., Jia, B., Mao, H., and Zhao, X.: Plant species richness and legume presence increase microbial necromass carbon accumulation, Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment, 374, 109196, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2024.109196, 2024.

Mueller, C. W., Baumert, V., Carminati, A., Germon, A., Holz, M., Kögel-Knabner, I., Peth, S., Schlüter, S., Uteau, D., and Vetterlein, D.: From rhizosphere to detritusphere–Soil structure formation driven by plant roots and the interactions with soil biota, Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 193, 109396, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2024.109396, 2024.

Münch, B. and Holzer, L.: Contradicting geometrical concepts in pore size analysis attained with electron microscopy and mercury intrusion, Journal of the American Ceramic Society, 91, 4059–4067, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1551-2916.2008.02736.x, 2008.

Pierret, A., Moran, C., and Pankhurst, C.: Differentiation of soil properties related to the spatial association of wheat roots and soil macropores, Plant and Soil, 211, 51–58, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004490800536, 1999.

Prommer, J., Walker, T. W., Wanek, W., Braun, J., Zezula, D., Hu, Y., Hofhansl, F., and Richter, A.: Increased microbial growth, biomass, and turnover drive soil organic carbon accumulation at higher plant diversity, Global Change Biology, 26, 669–681, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14777, 2020.

Qian, Z., Li, Y., Du, H., Wang, K., Li, D.: Increasing plant species diversity enhances microbial necromass carbon content but does not alter its contribution to soil organic carbon pool in a subtropical forest, Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 187, 109183, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2023.109183, 2023.

Quigley, M. and Kravchenko, A.: Inputs of root-derived carbon into soil and its losses are associated with pore-size distributions, Geoderma, 410, 115667, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2021.115667, 2022.

Robertson, G. P. and Hamilton, S. K.: Long-term ecological research at the Kellogg Biological Station LTER site. The ecology of agricultural landscapes: Long-term research on the path to sustainability 1, 32, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, ISBN 9780199773350, 2015.

Roosendaal, D., Stewart, C. E., Denef, K., Follett, R. F., Pruessner, E., Comas, L. H., Varvel, G. E., Saathoff, A., Palmer, N., Sarath, G., Jin, V. L., Schmer, M., and Soundararajan, M.: Switchgrass ecotypes alter microbial contribution to deep-soil C, SOIL, 2, 185–197, https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-2-185-2016, 2016.

Schindelin, J., Arganda-Carreras, I., Frise, E., Kaynig, V., Longair, M., Pietzsch, T., Preibisch, S., Rueden, C., Saalfeld, S., and Schmid, B.: Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis, Nature Methods, 9, 676–682, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2019, 2012.

Schlüter, S., Sheppard, A., Brown, K., and Wildenschild, D.: Image processing of multiphase images obtained via X-ray microtomography: A review, Water Resources Research, 50, 3615–3639, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014WR015256, 2014.

Silin, D. and Patzek, T.: Pore space morphology analysis using maximal inscribed spheres, Physica A-Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 371, 336–360, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2006.04.048, 2006.

Spiesman, B. J., Kummel, H., and Jackson, R. D.: Carbon storage potential increases with increasing ratio of C4 to C 3 grass cover and soil productivity in restored tallgrass prairies, Oecologia, 186, 565–576, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-017-4036-8, 2018.

Sprunger, C. D. and Robertson, G. P.: Early accumulation of active fraction soil carbon in newly established cellulosic biofuel systems, Geoderma, 318, 42–51, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2017.11.040, 2018.

Tilman, D., Reich, P. B., and Knops, J. M.: Biodiversity and ecosystem stability in a decade-long grassland experiment, Nature, 441, 629–632, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04742, 2006.

Ulbrich, T. C., Rivas-Ubach, A., Tiemann, L. K., Friesen, M. L., and Evans, S. E.: Plant root exudates and rhizosphere bacterial communities shift with neighbor context, Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 172, 108753, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2022.108753, 2022.

Wahlström, E. M., Kristensen, H. L., Thomsen, I. K., Labouriau, R., Pulido-Moncada, M., Nielsen, J. A., and Munkholm, L. J.: Subsoil compaction effect on spatio-temporal root growth, reuse of biopores and crop yield of spring barley, European Journal of Agronomy, 123, 126225, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2020.126225, 2021.

Wang, B., Zhang, W., Ahanbieke, P., Gan, Y., Xu, W., Li, L., Christie, P., and Li, L.: Interspecific interactions alter root length density, root diameter and specific root length in jujube/wheat agroforestry systems, Agroforestry Systems, 88, 835–850, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-014-9729-y, 2014.

Wang, X.-Y., Ge, Y., and Wang, J.: Positive effects of plant diversity on soil microbial biomass and activity are associated with more root biomass production, Journal of Plant Interactions, 12, 533–541, https://doi.org/10.1080/17429145.2017.1400123, 2017.

Wendel, A. S., Bauke, S. L., Amelung, W., and Knief, C.: Root-rhizosphere-soil interactions in biopores, Plant and Soil, 475, 253–277, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-022-05406-4, 2022.

White, R. G. and Kirkegaard, J. A.: The distribution and abundance of wheat roots in a dense, structured subsoil–implications for water uptake, Plant Cell & Environment, 33, 133–148, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02059.x, 2010.

Xiong, P., Zhang, Z., and Peng, X.: Root and root-derived biopore interactions in soils: A review, Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science, 185, 643–655, https://doi.org/10.1002/jpln.202200003, 2022.

Yang, Y. and Tilman, D.: Soil and root carbon storage is key to climate benefits of bioenergy crops, Biofuel Research Journal, 7, 1143–1148, https://doi.org/10.18331/BRJ2020.7.2.2, 2020.

Yang, Y., Tilman, D., Furey, G., and Lehman, C.: Soil carbon sequestration accelerated by restoration of grassland biodiversity, Nature Communications, 10, 718, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08636-w, 2019.

Zahorec, A., Reid, M. L., Tiemann, L. K., and Landis, D. A.: Perennial grass bioenergy cropping systems: Impacts on soil fauna and implications for soil carbon accrual, GCB Bioenergy, 14, 4–23, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcbb.12903, 2022.

Zegada-Lizarazu, W., Zanetti, F., Di Virgilio, N., and Monti, A.: Is switchgrass good for carbon savings? Long-term results in marginal land, GCB Bioenergy, 14, 814–823, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcbb.12944, 2022.