the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Inducing banana Fusarium wilt disease suppression through soil microbiome reshaping by pineapple–banana rotation combined with biofertilizer application

Beibei Wang

Mingze Sun

Jinming Yang

Zongzhuan Shen

Yannan Ou

Lin Fu

Yan Zhao

Rong Li

Yunze Ruan

Qirong Shen

Crop rotation and biofertilizer application have historically been employed as efficient management strategies for soil-borne disease suppression through soil microbiome manipulation. However, how this occurs and to what extent the combination of methods affects the microbiota reconstruction of diseased soil is unknown. In this study, pineapple–banana rotation combined with biofertilizer application was used to suppress banana Fusarium wilt disease, and the effects on both bacterial and fungal communities were investigated using the MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform. Our results showed that pineapple–banana rotation significantly reduced Fusarium wilt disease incidence and the application of biofertilizer caused additional suppression. Bacterial and fungal communities thrived using rotation combined with biofertilizer application: taxonomic and phylogenetic α diversity of both bacteria and fungi increased along with disease suppression. Between the two strategies, biofertilizer application predominantly affected both bacterial and fungal community composition compared to rotation. Burkholderia genus may have been attributed to the general wilt suppression for its change in network structure and high relative importance in linear models. Our results indicated that pineapple–banana rotation combined with biofertilizer application has strong potential for the sustainable management of banana Fusarium wilt disease.

- Article

(3385 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(210 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Banana Fusarium wilt disease caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense (FOC) race 4 forms a major constraint on the yield and quality of banana production (Ploetz, 2015; Butler, 2013). Multiple studies have revealed that individual measures, such as fumigation (Duniway, 2003; Liu et al., 2016), chemical fungicides (Nel et al., 2007), crop rotation (Zhang et al., 2013b), and bio-control (Wang et al., 2013), have particular effects on reducing the incidence of soil-borne diseases by disrupting soil microbial community membership and structure. Traditionally, fumigation, chemical fungicides, or crop rotation is used in fields with high incidence rates, and bio-control is used in low- or new-incidence fields because of its apparent mild effect (Shen et al., 2018). However, single measures often have limited effectiveness, and a few studies regarding soil-borne disease suppression focused on using multiple strategies to improve control efficiency. For example, Shen et al. (2018) reported that biofertilizer application after fumigation with lime and ammonium bicarbonate was an effective strategy to control banana Fusarium wilt disease. Thus, while many measures can individually slow down the spread of Fusarium wilt disease (Pda et al., 2017), control effects can be accelerated and amplified by using more than one agricultural practice.

Among the management strategies, chemical pesticides are optimally effective against soil-borne plant pathogens, but this strategy is environmentally hazardous, and not only causes soil and water pollution but also induces the emergence of drug-resistant strains (Le et al., 2016). Biological control using beneficial soil microorganisms such as Bacillus and Trichoderma against soil-borne pathogens is considered as a sustainable alternative to chemical pesticides (Alabouvette et al., 2009; Fravel et al., 2003; Qiu et al., 2012). Biofertilizers combine the advantages of introducing beneficial microbes with organic material that not only occupy niches but also create additional niches for beneficial indigenous microbes (Cai et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2013). In our previous study, we developed a biofertilizer containing the Bacillus strain isolated from the rhizosphere of a continuously cropped banana that promoted plant growth and suppressed the banana Fusarium wilt (Shen et al., 2015; Fu et al., 2016, 2017). Therefore, biofertilizer application is a practicable and worthy measure for banana Fusarium wilt suppression.

In addition, crop rotation is also considered a highly efficient and environmentally friendly alternative method in soil-borne disease control (Krupinsky et al., 2002). Crop rotation breaks the microflora and chemical characteristics of continuously mono-cropped soil leading to the control of soil-borne diseases (Christen and Sieling, 2010; Yin et al., 2010). The mechanisms of soil-borne disease suppression induced by crop rotation include inhibition of pathogen reproduction through allelochemical secretion, stimulation of antagonistic microbes against pathogens, and improvement of rhizosphere microbial community structure by introducing different carbon compounds into the soil through root exudates or residues (Robert et al., 2014). In our previous study, besides biofertilizer application, our work also showed that the banana–pineapple rotation efficiently suppressed the banana Fusarium wilt disease (Wang et al., 2015). However, the combined control efficiency of the two measures (pineapple–banana rotation plus biofertilizer application) remains unknown. Thus, there is a great need to explore efficient disease suppressing-combined approaches for the banana Fusarium wilt control and to progress towards maintaining sustainable worldwide industrial banana development.

The occurrence of soil-borne disease is mainly due to the imbalance of soil microbial communities caused by soil-borne pathogen blooms (Mendes et al., 2014). Effective soil-borne disease suppression management strategies must demonstrate significant changes in the soil microbial community in addition to pathogen minimization (Cha et al., 2016; Chaparro et al., 2012; Gerbore et al., 2014; Mazzola and Freilich, 2017). Our previous reports proved the effectiveness of microbial agents for biocontrol by changing the structure of soil microbial communities (Fu et al., 2017; Shen et al., 2015). We also investigated the influences of quarterly rotation (pineapple) on Fusarium population density and soil microbial community structure while attempting to explore the mechanisms of pineapple–banana rotation on soil-borne disease suppression (Wang et al., 2015). Our results suggested that fungal community structure and several genera introduced in the rotation season may have been the most critical factors in decreasing soil Fusarium population.

Unlike intercropping, controlling Fusarium pathogen accumulation through effective crop rotation should be maintained for at least two seasons, including rotation and a subsequent season (Bullock, 1992; Lupwayi et al., 1998). The pineapple and banana growth cycles in our rotation pattern require long durations (almost 15 and 10 months, respectively, in Hainan Province, China). Thus, the soil microbial community structure of the original season is very important in evaluating rotation validity. Furthermore, how the soil microbial community structure changes using the combined control efficiencies of the two measures (pineapple–banana rotation and biofertilizer application) remains unknown.

We hypothesized that Fusarium wilt can be effectively controlled in high-disease incidence fields by pineapple–banana rotation and that the control efficiency can be improved by adding biocontrol to the rotation. In addition, this scheme will concurrently change the soil microbial community membership and structure. Therefore, based on our previous research, we conducted field experiments to investigate the effects of pineapple–banana rotation combined with biofertilizer on next season banana Fusarium wilt disease suppression and soil microbial communities. Our objectives were to (1) determine the direct effects of pineapple–banana rotation alone and pineapple–banana rotation combined with biofertilizer application to control banana Fusarium wilt disease, (2) explore the characteristics of the soil microbial communities prompted by crop rotation and biocontrol strategies after banana harvest using the MiSeq platform, and (3) evaluate the probable disease suppression mechanisms caused by rotation and biocontrol strategy.

2.1 Field experimental design

The field experiment was set up at the site of Hainan Wanzhong Industrial Co., Ltd., China, a company that specialized in banana planting during December 2011 to June 2014. The field soil had a chemical background of pH 5.12, soil organic matter (SOM) 5.57 g kg−1, NH-N 7.39 mg kg−1, NO-N 6.68 mg kg−1, available P 56.9 mg kg−1 and available K 176.4 mg kg−1. The organic fertilizer (OF) used in our study was supplied by Lianye Biofertilizer Engineering Center, Ltd., Jiangsu, China, which was the first fermentation of amino acid fertilizer and pig manure with a 2:3 weight ratio, respectively. The biofertilizer (BIO) was a secondary fermentation based on OF according to the solid fermentation method (Wang et al., 2013). The research was carried out in a field in which a serious Fusarium wilt disease incidence (> 50 %) was observed after continuous banana cropping for 6 years. Nine replicates were set up in each treatment with a randomized complete block design, and the area of each block was 300 m2. Banana cultivar Musa acuminata AAA Cavendish cv. Brazil and the pineapple cultivar Golden pineapple were used in the field experiment. Three treatments were assigned: (1) banana continuously cropped for 2 years with common organic fertilizer application (BOF); (2) banana planted after an 18-month pineapple rotation with common organic fertilizer application in the banana season (POF); and (3) banana planted after an 18-month pineapple rotation treatment with biofertilizer application (PBIO). In the rotation system, pineapple and banana were planted at the densities of 45 000 and 2400 seedlings ha−1, respectively. All organic fertilizer was applied to the soil at once as base fertilizer before banana planting. Other measures were consistent with common banana production.

2.2 Banana Fusarium wilt disease incidence statistics

Old leaves yellowing, stem crack and new leaves diminishing were the three typical wilt symptoms of banana Fusarium wilt disease. Disease incidence was calculated based on the appearance of all three symptoms weekly since the first sick banana plant appeared. Finally, banana wilt disease incidence was determined at the harvest time. The percentage of sick plants among the total banana plants was calculated as the Fusarium wilt disease incidence.

2.3 Soil sample collection and DNA extraction

During the harvest time of last banana planting season, five healthy plants were randomly picked in each biological replicate plot for soil sampling. Soil samples were collected from four random sites around the banana plant at 10 cm distance, and a soil column was picked out at the depth of 20 cm using a soil borer at each sampling site. All five soil columns from each biological replicate plot were mixed for DNA extraction. All mixed samples were placed in cold storage and transported to the laboratory. After passing soil through a 2 mm sieve, total soil DNA was extracted using Clean Soil DNA Isolation Kits (MoBio Laboratories Inc., Carlsbad, USA) from fine-grained soil. After the determination of DNA concentration and quality using NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific, USA), soil DNA was diluted to a concentration of 20 ng µL−1 for PCR amplification.

2.4 Polymerase chain reaction amplification and Illumina MiSeq sequencing

Primers F520 (5′-AYTGGGYDTAAAGNG-3′) and R802 (5′-TACNVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′) were chosen to amplify the V4 regions of 16S rRNA gene (Claesson et al., 2009). Primers ITS (5′-GGA AGT AAA AGT CGT AAC AAG G-3′) and ITS (5′-TCC TCC GCT TAT TGA TAT GC-3′) were chosen for amplification of the fungal ITS region (Schoch et al., 2012).

PCR reactions for each sample were performed according to the established protocols of Xiong et al. (2016). A total of 27 cycles were performed to amplify the templates. After purification, PCR products were diluted to a concentration of 10 ng µL−1. Fungal and bacterial PCR product sequencing were performed on the Illumina MiSeq platform of Personal Biological Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China).

2.5 Bioinformatic analysis

Raw sequences were separated based on the unique 6 bp barcode and sheared of the adaptor and primer using QIIME (Caporaso et al., 2010). Forward and reverse sequences were merged after the removal of low-quality sequences. Then, the merged sequences were processed to build the operational taxonomic unit (OTU) at an identity level of 97 % according to the UPARSE pipeline. Next, representative sequences of each OTU were classified in the RDP and UNITE databases for bacteria and fungi, respectively (Edgar, 2013; Wang et al., 2007). All raw sequences were deposited in NCBI under the accession number SRP234066.

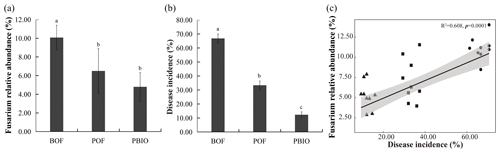

Figure 1Relative abundance of Fusarium (a), Fusarium wilt disease incidence (b), and Pearson correlations between Fusarium wilt disease incidence and Fusarium relative abundance (c). BOF – banana continuously cropped with OF application; POF – banana–pineapple rotation with OF application in the banana season; and PBIO – ,banana–pineapple rotation with BIO application in the banana season. Bars above the histogram represent standard errors and different letters indicate significant differences (p<0.05) according to multivariate variance analysis and multiple comparison results.

To compare the relative levels of OTU diversity across all samples, a rarefaction curve was formed using Mothur software (Schloss et al., 2009). The fungal and bacterial diversity was estimated using phylogenetic diversity (PD) indices and Chao1 richness, which were also calculated based on neighbour-joining phylogenetic trees generated using Mothur pipeline (Faith, 1992).

To compare bacterial and fungal community structures among all soil samples, principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was set up based on the unweighted UniFrac metric matrix (Lozupone et al., 2005). Multiple regression tree (MRT), based on Bray–Curtis distance metric, was carried out to evaluate the effects of rotation and fertilizer type on the whole soil bacterial and fungal community by using vegan and MVPART wrap package in R (version 3.2.0). In addition, to exclude the influence of low abundance species, only the OTUs with the average relative abundance of equal or greater than 0.1 % in each sample were retained (defined as retained OTUs).

2.6 Network analyses

Based on retained OTUs, interaction networks between OTUs were constructed using the phylogenetic molecular ecological network (pMEN) method according to Zhou et al. (2011) and Deng et al. (2012). All analyses were performed using the Molecular Ecological Network Analyses Pipeline (MENA). Cytoscape 2.8.2 software was used to visualize the network.

2.7 Statistical analysis

Statistical difference analysis among three treatments was carried out using SPSS 20.0 and R software. Pearson correlations among disease incidence, different phylum and Fusarium relative abundance were analysed in R. Linear model analysis was performed using R after stepwise model selection considering Akaike information criteria.

3.1 Disease incidence and relative abundance of Fusarium

Pineapple rotation and biofertilizer application effectively reduced the Fusarium wilt disease incidence and the relative abundance of Fusarium in the next season's banana plantation (Fig. 1a, b). The incidence of banana Fusarium wilt in the POF and PBIO treatments was 33.3 % and 12.3 %, respectively, which was significantly lower than that in the BOF treatment (66.8 %). PBIO treatment of rotation and biofertilizer application showed the lowest disease incidence with a 63.1 % decrease compared to POF (Fig. 1b and Table S1). The relative abundance of Fusarium showed the same tendency with disease incidence, so the relative abundance of Fusarium and disease incidence were significantly correlated as revealed by MiSeq sequencing data (Fig. 1c).

3.2 General analyses of the high-throughput sequencing data

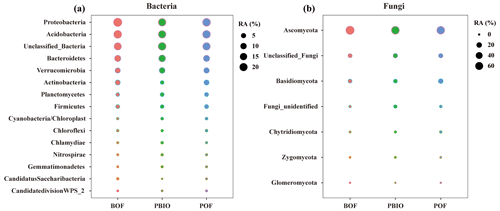

After quality control, 908 506 16S rRNA and 1 950 262 ITS sequences were retained and based on 97 % similarity, a total of 8346 16S and 5647 ITS operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were obtained. For bacteria, Acidobacteria, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria and Verrucomicrobia were the most abundant phyla with >1 % relative abundances. For fungi, Ascomycota, followed by Basidiomycota, Chytridiomycota, Zycomycota, and Glomeromycota were the abundant phyla (Fig. 2). ANOVA showed that Chlamydiae, Cyanobacteria/chloroplast, Gemmatimonadetes, Nitrospirae, Planctomycetes, and Verrucomicrobia abundances were significantly higher in the PBIO and POF treatment samples than those in the BOF treatment, and the relative abundance of Ascomycota was lower in the PBIO treatment (Duncan test, p<0.05).

Figure 2Bubble chart of bacterial (a) and fungal (b) phyla in BOF, POF and PBIO treatments. BOF – banana continuously cropped with OF application; POF – banana–pineapple rotation with OF application in the banana season; and PBIO – ,banana–pineapple rotation with BIO application in the banana season; values represent the average abundance across the nine replicate libraries for soil samples collected from each treatment.

3.3 Effect of pineapple rotation and biofertilizer application on soil microbial diversity and community structure

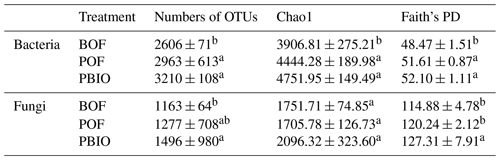

Rarefaction analyses, Chao1 and Faith's PD were performed to characterize α diversity. Rarefaction analyses showed that the number of OTUs tended to smooth at 14 900 selected bacterial sequences and 34 943 fungal sequences. Compared to BOF treatment, more OTUs were observed in POF and PBIO treatments, both for bacteria and fungi, and the PBIO treatment exhibited the highest value of all treatments (Table 1, Fig. S1). Compared to BOF treatment, the pineapple–banana rotation treatments, POF and PBIO, increased both taxonomic and phylogenetic α diversity of both bacteria and fungi. In addition, PBIO treatment showed the highest Chao1 richness and Faith's PD values (Table 1).

Table 1Bacterial and fungal α-diversity indexes of the three treatments. BOF – banana continuously cropped with OF application; POF – banana–pineapple rotation with OF application in the banana season; PBIO – banana–pineapple rotation with BIO application in the banana season; values represent the average index of nine replicates. Means followed by different letters for a given factor are significantly different (p<0.05; Duncan test).

Different letters indicate significant differences (p<0.05) among the three treatments within the same factor (Duncan's test).

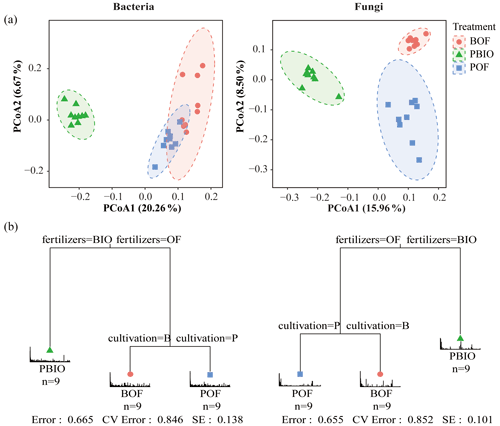

We evaluated microbial community structure by using PCoA based on a UniFrac unweighted distance matrix to analyse differences in community composition of three treatments. Fungal PCoA showed three distinct groups representing samples taken from three treatments; however, bacterial PCoA showed only two groups. Unweighted UniFrac distances showed that PBIO treatment was separate from BOF and POF treatments along the first component (PCoA1) both in bacteria and fungi. POF treatment was separated from BOF treatment along the second component in fungi, whereas in bacteria, POF and BOF treatments were not separate along the second component (Fig. 3a).

Furthermore, MRT results indicated that biofertilizer application had the largest deterministic influence on the composition of both bacterial and fungal communities, and cultivation was secondarily important. Driven by fertilization, PBIO treatment was separated from BOF and POF treatments, and then BOF and POF treatments were driven by cultivation (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3(a) UniFrac-unweighted principal coordinate analysis of fungal and bacterial community structures in different treatments. (b) Multiple regression tree (MRT) analysis for the bacterial and fungal communities showed the variables of fertilization and cultivation in each branch. BOF – banana continuously cropped with OF application; POF – banana–pineapple rotation with OF application in the banana season; PBIO – banana–pineapple rotation with BIO application in the banana season.

3.4 Effect of pineapple rotation and biofertilizer application on soil fungal and bacterial community composition

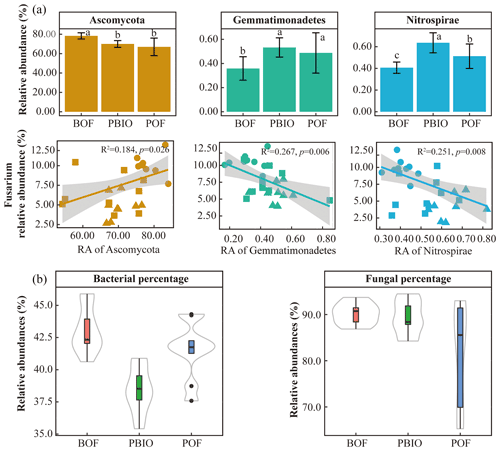

The results of the phyla correlation with Fusarium abundance showed that seven bacterial phyla and three fungal phyla were significantly correlated with pathogen abundance (Tables S3 and S4). Moreover, the correlation of fungi was significantly higher with Fusarium abundance compared to bacteria based on the percentage of Fusarium-related phyla (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4Relative abundance of key phyla and linear regression relationship between key phyla and disease incidence (a). Percentage of Fusarium-related bacterial and fungal phyla in all treatments (b). BOF – banana continuously cropped with OF application; POF – banana–pineapple rotation with OF application in the banana season; PBIO – banana–pineapple rotation with BIO application in the banana season. Different letters above the bars indicate a significant difference at the 0.05 probability level according to the Duncan test.

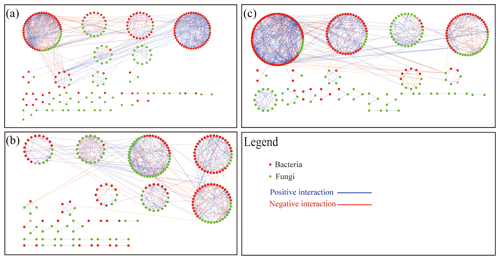

3.5 Key topological properties of the networks

We built networks to show interactions among genera in different treatments using OTUs with a relative abundance greater than 0.1 %. A total of 301 OTUs were selected from the BOF treatment (122 bacterial and 179 fungal), 323 OTUs were selected from the PBIO treatment (152 bacterial and 171 fungal), and 324 OTUs were selected from the POF treatment (140 bacterial and 184 fungal). Random matrix theory was used to build the networks. As shown in Fig. 5, each node represents an OTU, each link shows a significant correlation between two OTUs, red and green represent bacterial and fungal OTUs, respectively, and blue and red represent positive and negative correlations, respectively.

Figure 5Network plots of bacterial and fungal communities in soil BOF (a), PBIO (b) and POF (c). BOF – banana continuously cropped with OF application; POF – banana–pineapple rotation with OF application in the banana season; PBIO – ,banana–pineapple rotation with BIO application in the banana season; red nodes indicate bacteria; green nodes indicate fungi; red lines between nodes (links) indicate negative interaction; and blue lines indicate positive interaction.

Networks with 286 (143 bacterial and 98 fungal), 245 (122 bacterial and 123 fungal), and 241 (163 bacterial and 123 fungal) nodes were selected from the BOF, PBIO, and POF treatments, respectively. The ratios that represent the ratio of fungal to bacterial nodes were 0.69, 1.01, and 0.75 in the BOF, PBIO, and POF treatments, respectively. These results suggest more active fungal OTUs in the PBIO treatment followed by the POF and BOF treatments.

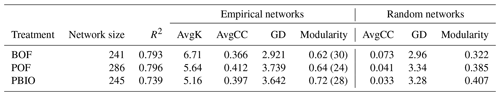

The structure index network from different treatments showed 24, 28, and 30 modules in the BOF, PBIO, and POF treatments, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2Topological properties of the empirical and associated random pMENs of microbial communities under BOF, POF and PBIO. BOF – banana continuously cropped with OF application; POF – banana–pineapple rotation with OF application in the banana season; PBIO – banana–pineapple rotation with BIO application in the banana season; AvgK – average connectivity; AvgCC – average clustering coefficient; and GD – average path distance.

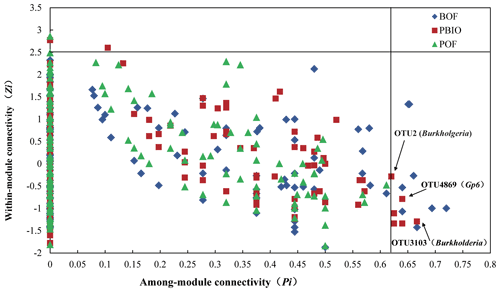

The threshold value Zi measures the connected degree between two nodes in the same module, and Pi measures the connected degree between two nodes from different modules. According to the Zi and Pi values found in our study, all nodes were divided into four categories (Fig. 6). Three nodes, two from the PBIO network and one from the POF network, were categorized as generalists (module hubs) with intense connectivity to many nodes in the same modules. However, there was no module hub found in the BOF network. Fourteen nodes were categorized as connectors (generalists) with high connectivity to several modules, eight from the BOF network and six from the PBIO network. Interestingly, module hubs (generalists) were only found in the pineapple–banana treatments (PBIO and POF), and connectors (generalists) and module hubs (generalists) were found at the same time only in the pineapple–banana with the biofertilizer applied treatment (PBIO). Annotation information from all generalists showed that bacterial OTU2 and OTU3013 belonging to Burkholderia were generalists in the PBIO network but were absent in the POF and BOF networks. Additionally, another generalist OTU4869 from the PBIO network was identified as Gp6 in Acidobacteria.

Figure 6Zi–Pi plot showing the distribution of OTUs based on their topological roles. Each symbol represents an OTU in different treatment. BOF – banana continuously cropped with OF application; POF – banana–pineapple rotation with OF application in the banana season; PBIO – banana–pineapple rotation with BIO application in the banana season; the threshold values of Zi and Pi for categorizing OTUs were 2.5 and 0.62, respectively, as proposed by Guimera and Amaral (2005) and simplified by Olesen et al. (2007).

3.6 Relationship between microbial indicators and incidence of banana Fusarium wilt disease

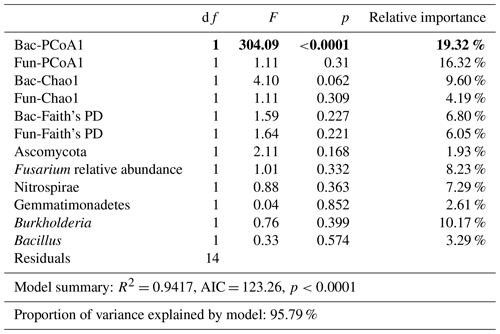

Bacterial and fungal structure (unweighted PCoA1), richness (Chao1), and Faith's PD; Ascomycota, Gemmatimonadetes, and Nitrospirae phyla relative abundances; and Fusarium, Burkholderia, and Bacillus genus relative abundances were selected in the linear model and explored for the best contribution factor of disease incidence (Table 3).

Table 3Linear models (LMs) for the relationships of microbial indicators with disease incidence and the relative importance of each indicator. p was the result from ANOVAs. The bold values represent p values lower than 0.05 from the ANOVA results.

Importantly, bacterial structure (F=304.09, p<0.0001, relative importance = 19.32 %), fungal structure (F=1.11, p<0.31, relative importance = 16.32 %), and Burkholderia relative abundance (F=0.76, p<0.399, relative importance = 10.17 %) contributed most in constraining disease incidence (with a relative importance greater than 10 %).

In addition, based on linear regression analyses between disease incidence and selected microbial indicators, we found that bacterial structure (F=304.09, p<0.0001, relative importance = 19.32 %) had a significant relationship with disease incidence.

In our previous research, the effectiveness of pineapple–banana rotation and biofertilizer application was proven in the control of banana Fusarium wilt disease (Wang et al., 2015; Fu et al., 2017). Soil microbial community change is an important indicator of exploring the mechanisms behind these two control measures. In this study, disease incidence and soil microbial community characteristics during the banana-growing season were measured to evaluate the control effect and potential impact of combined use of rotation and biofertilizer application.

Our previous results indicated that the pineapple–banana rotation treatments significantly reduced the Fusarium wilt disease incidence when compared with banana monoculture. Moreover, the application of biofertilizer enhances this suppression ability. Similar to our results, Shen et al. (2018) reported that bio-fertilizer application after fumigation with lime and ammonium bicarbonate revealed higher effectiveness in controlling banana Fusarium wilt disease compared to bio-fertilizer application or fumigation only. Although many control measures can slow down the spread of Fusarium wilt disease, more effective control can be achieved by the combined use of more than one measure (Pda et al., 2017). It was consistent with this paper.

In this study, Chao1 and Faith's PD were significantly higher in the combined rotation and biofertilizer treatment (PBIO) compared to the other two treatments (BOF and POF). Previous studies have shown a positive correlation between disease suppression and bacterial but not fungal diversity (Bonanomi et al., 2010; Fu et al., 2017). Inconsistent with these results, pineapple–banana rotation and biofertilizer treatment (PBIO) harboured a significantly higher fungal richness and diversity than the other two treatments (BOF and POF). This agrees with some other previous studies that observed the importance of fungal diversity in the suppressive capacity of vanilla soils and potato cropping systems (Lu et al., 2013; Xiong et al., 2017). We also observed that soil pH was increased in the rotation and biofertilizer treatment (Table S2). Many previous studies have shown that microbial diversity has been seen to increase with higher soil pH values (Liu et al., 2014; Shen et al., 2013). Therefore, the high bacterial and fungal diversity observed in PBIO treatment may be attributed to the high soil pH.

Both PCoA ordinations and MRT results revealed significant differences in microbial community structure after rotation and biofertilizer applications. This is supported by previous studies stating that rotation (Helena et al., 2016; Hartmann et al., 2015) and biofertilizer application (Sun et al., 2015) altered the soil microbial community composition. MRT analysis also revealed fertilization effects on microbial community composition. These results are similar to previous results where biofertilizer application was the dominant factor in determining microbial community composition rather than temporal variability (Fu et al., 2017), suggesting a powerful illustration of the necessity of biofertilizer application in pineapple–banana rotation system.

Phylum-level results show that rotation and biofertilizer application decreased the relative abundance of Ascomycota and increased the relative abundance of Chlamydiae, Gemmatimonadetes, Nitrospirae, Planctomycetes, and Verrucomicrobia, which were all reported to be associated with disease suppression in previous reports (Trivedi et al., 2017; Shen et al., 2018).

It is worth noting that our BIO was secondary fermentation with Bacillus added, while the Bacillus genus was not enriched in the BIO treatment soil. Moreover, the microbial structure appeared to be the most constrained factor in disease incidence in linear models between microbial indicators and the incidence of banana Fusarium wilt disease. Xiong et al. (2017) suggested that microbial species introduced by biofertilizer application induced wilt suppression by microbiome manipulation rather than pathogen suppression directly. Thus, alteration of the soil microbiome may cause a greater response than the added Bacillus in the PBIO treatment in our case.

Compared with bacteria, a higher percentage of Fusarium-related fungi genera were observed in all treatments. Even though more kinds of bacteria are related to Fusarium, a higher percentage of fungi showed relevance compared to bacteria. These results agree with the findings of Mona et al. (2014) and Cai et al. (2017), who reported that fungal communities have a more crucial response to soil factor changes than bacterial communities. It is worth noting that fungal communities were more dissimilar between the pineapple–banana rotation and maize–banana rotation treatments than bacteria in our previous study (Wang et al., 2015). Thus, the higher Fusarium relevance observed in the fungal community in both the pineapple and banana seasons further reinforced the importance of fungal community changes in our case.

Several researchers have used microbial molecular ecological networks to study complex microbial ecological systems in suppressed soils, including corn–potato rotations (Lu et al., 2013) and vanilla (Xiong et al., 2017). In our study, the microbial molecular ecological networks revealed distinct differences between the microbial communities associated with the three treatments. More fungal OTUs were selected in the PBIO treatment samples, followed by the POF and BOF treatments, based on the ratio. Although the OTUs selected to build the network were only a part of the entire system, there is no doubt that these OTUs were very important for soil function (Coyte et al., 2015). Therefore, we conclude that a large number of fungal OTUs present in the system may have led to changes in soil function. PBIO, POF, and BOF soils harboured modules with modularity values of 0.718, 0.642, and 0.616, respectively, in this study. Modularity represents how well the network was organized (Zhou et al., 2011). Thus, the PBIO network, which possessed high modularity, had more connections between nodes in the same modules, followed by the POF and BOF networks. The altered networks compared to POF and BOF networks may have partially contributed latent attributes to higher disease suppression in PBIO treatment. Furthermore, no module hubs (generalists) were present in the BOF network, whereas all three module hubs were found in the pineapple–banana rotation network, as indicated by the Zi–Pi relationship. In all three networks, connectors (generalists) and module hubs (generalists) were found at the same time only in the PBIO treatment. Generalists typically only occupy a small fraction of a community; however, the presence of those generalists is very important (Zhou et al., 2011; Jens et al., 2011). These nodes could have enhanced connectors within or among modules. If the network is poorly connected or not connected at all, the community is predicted to be disordered, and fluxes of energy, material, and information would not be efficient (Lu et al., 2013). Therefore, in our case, these generalists found in the PBIO treatment suggest that the microbial community structure of PBIO treatment was more orderly and powerful than the other two treatments.

Annotation information from all generalists found in our study shows that bacterial OTU2 and OTU3013 belong to Burkholderia, which were generalists in the PBIO but not in POF and BOF networks. The linear model analysis also shows that Burkholderia relative abundance constrained disease incidence with a higher relative importance factor of 10.17 %. Correspondingly, a high abundance of Burkholderia and a high percentage of antagonistic Burkholderia were found during the pineapple season in our previous report (Wang et al., 2015). Burkholderia is a versatile organism due to its powerful ability to occupy ecological niches and a variety of functions, including biological control and plant growth promotion in agriculture (Coenye and Vandamme, 2003). Thus, even though the relative abundance of Burkholderia in the PBIO treatment was not that high, its change in network structure may have been attributed to the general wilt suppression activity, which is the special function of Burkholderia. Additionally, one generalist in the PBIO treatment sample was identified as Gp6 in Acidobacteria. Although no Acidobacteria antimicrobial activities have previously been recorded, several studies have demonstrated that Acidobacteria is greatly affected by soil pH and that the Gp6 is positively correlated with soil pH (Bartram et al., 2014; Jones et al., 2009).

This study was an expansion of our previous work. The results revealed that pineapple–banana rotation combined with biofertilizer application during the banana season effectively reduced the Fusarium spp. abundance and banana Fusarium wilt. Both bacterial and fungal taxonomic and phylogenetic α diversity was increased by rotation and biofertilizer application. Between the two strategies, biofertilizer application affected both bacterial and fungal community composition more predominantly compared to rotation. A higher percentage of Fusarium-related fungal phyla was observed compared to bacterial. More specifically, the potentially beneficial Burkholderia genus may attribute to the general wilt suppression activity for its important role in network structure and its high relative importance in linear models. Pineapple–banana rotation combined with biofertilizer application has strong potential for the sustainable management of banana Fusarium wilt disease.

The sequencing data have been submitted to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive database: SRP234066, https://trace.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/sra/?study=SRP234066, last access: 23 December 2021 (Wang et al., 2021).

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-8-17-2022-supplement.

RL and BW designed the research and wrote the manuscript. BW, YO and ZS performed trials and conducted fieldwork. BW and JY analysed the data. RL, MS, LF, YR, YZ and QS participated in the design of the study, provided comments and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The contact author has declared that neither they nor their co-authors have any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41867006 and 31760605), the Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (320RC483), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFD0202101).

This research has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 41867006 and 31760605), the Natural Science Foundation of Hainan Province (grant no. 320RC483), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China, Chinese Polar Environment Comprehensive Investigation and Assessment Programmes (grant no. 2017YFD0202101).

This paper was edited by Ping He and reviewed by Wei Wang and one anonymous referee.

Alabouvette, C., Olivain, C., Migheli, Q., and Steinberg, C.: Microbiological control of soil-borne phytopathogenic fungi with special emphasis on wilt-inducing Fusarium oxysporum, New Phytol., 184, 529–544, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03014.x, 2009.

Bartram, A. K., Jiang, X., Lynch, M. D. J., Masella, A. P., Nicol, G. W., Jonathan, D., and Neufeld, J. D.: Exploring links between pH and bacterial community composition in soils from the Craibstone Experimental Farm, FEMS Microbiol. Ecol., 87, 403415, https://doi.org/10.1111/1574-6941.12231, 2014.

Bonanomi, G., Antignani, V., Capodilupo, M., and Scala, F.: Identifying the characteristics of organic soil amendments that suppress soilborne plant diseases, Soil Biol. Biochem., 42, 136–144, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.10.012, 2010.

Bullock, D. G.: Crop rotation, Crit. Rev. Plant. Sci., 11, 309–326, https://doi.org/10.1080/07352689209382349, 1992.

Butler, D.: Fungus threatens top banana, Nature, 504, 195–196, https://doi.org/10.1038/504195a, 2013.

Cai, F., Pang, G., Li, R. X., Li, R., Gu, X. L., Shen, Q. R., and Chen, W.: Bioorganic fertilizer maintains a more stable soil microbiome than chemical fertilizer for monocropping, Biol. Fertil. Soils, 53, 861–872, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-017-1216-y, 2017.

Caporaso, J. G., Kuczynski, J., Stombaugh, J., Bittinger, K., Bushman, F. D., Costello, E. K., Fierer, N., Peña, A., Goodrich, J. K., and Gordon, J. I.: QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data, Nat. Methods., 7, 335–336, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.f.303, 2010.

Cha, J. Y., Han, S., Hong, H. J., Cho, H., and Kwak, Y. S.: Microbial and biochemical basis of a Fusarium wilt-suppressive soil, ISME J., 10, 119–129, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2015.95, 2016.

Chaparro, J. M., Sheflin, A. M., Manter, D. K., and Vivanco, J. M.: Manipulating the soil microbiome to increase soil health and plant fertility, Biol. Fertil. Soils, 48, 489–499, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-012-0691-4, 2012.

Christen, O. and Sieling, K.: Effect of Different Preceding Crops and Crop Rotations on Yield of Winter Oil-seed Rape (Brassica napus L.), J. Agron. Crop. Sci., 174, 265–271, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-037X.1995.tb01112.x, 2010.

Claesson, M. J., O'Sullivan, O., Wang, Q., Nikkila, J., and Marchesi, J. R.: Comparative Analysis of Pyrosequencing and a Phylogenetic Microarray for Exploring Microbial Community Structures in the Human Distal Intestine, PLoS One, 4, e6669, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0006669, 2009.

Coenye, T. and Vandamme, P.: Diversity and significance of Burkholderia species occupying diverse ecological niches, Environ. Microbiol., 5, 719–729, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00471.x, 2003.

Coyte, K. Z., Schluter, J., and Foster, K. R.: The ecology of the microbiome: Networks, competition, and stability, Science, 350, 663–666, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad2602, 2015.

Deng, Y., Jiang, Y., Yang, Y., He, Z., Luo, F., and Zhou, J.: Molecular ecological network analyses, BMC Bioinfo., 13, 113, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-13-113, 2012.

Duniway, J. M.: Status of Chemical Alternatives to Methyl Bromide for Pre-Plant Fumigation of Soil, Phytopathology, 92, 1337–1343, https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO.2002.92.12.1337, 2003.

Edgar, R. C.: UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads, Nat. Methods., 10, 996–998, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2604, 2013.

Faith, D. P.: Conservation evaluation and phylogenetic diversity, Biol. Conserv., 61, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3207(92)91201-3, 1992.

Fravel, D., Olivain, C., and Alabouvette, C.: Fusarium oxysporum and its biocontrol, New Phytol., 157, 493–502, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00700.x, 2003.

Fu, L., Ruan, Y., Tao, C., Li, R., and Shen, Q.: Continous application of bioorganic fertilizer induced resilient culturable bacteria community associated with banana Fusarium wilt suppression, Sci. Rep., 6, 27731, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27731, 2016.

Fu, L., Penton, C. R., Ruan, Y., Shen, Z., Xue, C., Li, R., and Shen, Q.: Inducing the rhizosphere microbiome by biofertilizer application to suppress banana Fusarium wilt disease, Soil Biol. Biochem., 104, 39–48, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2016.10.008, 2017.

Gerbore, J., Benhamou, N., Vallance, J., Floch, G., Grizard, D., Regnault-Roger, C., and Rey, P.: Biological control of plant pathogens: advantages and limitations seen through the case study of Pythium oligandrum, Environ. Sci. Pollut. R., 21, 4847–4860, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-013-1807-6, 2014.

Hartmann, M., Frey, B., Mayer, J., Mäder, P., and Widmer, F.: Distinct soil microbial diversity under long-term organic and conventional farming, ISME J., 9, 1177–1194, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2014.210, 2015.

Helena, C., Lurdes, B., Susana, R.-E., and Helena, F.: Trends in plant and soil microbial diversity associated with Mediterranean extensive cereal-fallow rotation agro-ecosystems, Agric. Ecosyst. Environ., 217, 33–40, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2015.10.027., 2016.

Jens, M. O., Jordi, B., Yoko, L. D., and Pedro, J.: The modularity of pollination networks, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 104, 19891–19896, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0706375104, 2011.

Jin, X., Wang, J., Li, D., Wu, F., and Zhou, X.: Rotations with Indian Mustard and Wild Rocket Suppressed Cucumber Fusarium Wilt Disease and Changed Rhizosphere Bacterial Communities, Microorganisms, 7, 57, https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7020057, 2019.

Jones, R. T., Robeson, M. S., Lauber, C. L., Hamady, M., Knight, R., and Fierer, N.: A comprehensive survey of soil acidobacterial diversity using pyrosequencing and clone library analyses, ISME J., 3, 442–453, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2008.127, 2009.

Krupinsky, J. M., Bailey, K. L., Mcmullen, M. P., Gossen, B. D., and Turkington, T. K.: Managing Plant Disease Risk in Diversified Cropping Systems, Agron J., 94, 198–209, https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2002.1980, 2002.

Le, C. R., Simon, T. E., Patrick, D., Maxime, H., Melen, L., Sylvain, P., and Sabrina, S.: Reducing the Use of Pesticides with Site-Specific Application: The Chemical Control of Rhizoctonia solani as a Case of Study for the Management of Soil-Borne Diseases, PLoS One, 11, e0163221, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0163221, 2016.

Liu, J., Sui, Y., Yu, Z., Shi, Y., Chu, H., Jin, J., Liu, X., and Wang, G.: High throughput sequencing analysis of biogeographical distribution of bacterial communities in the black soils of northeast China, Soil Biol. Biochem., 70, 113–122, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.12.014, 2014.

Liu, L., Kong, J., Cui, H., Zhang, J., Wang, F., Cai, Z., and Huang, X.: Relationships of decomposability and C/N ratio in different types of organic matter with suppression of Fusarium oxysporum and microbial communities during reductive soil disinfestation, Biol. Control., 101, 103–113, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2016.06.011, 2016.

Lozupone, C., Hamady, M., and Knight, R.: UniFrac–An online tool for comparing microbial community diversity in a phylogenetic context, Nat. New Biol., 241, 184–186, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-7-371, 2005.

Lu, L., Yin, S., Liu, X., Zhang, W., Gu, T., Shen, Q., and Qiu, H.: Fungal networks in yield-invigorating and -debilitating soils induced by prolonged potato monoculture, Soil Biol. Biochem., 65, 186–194, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.05.025, 2013.

Lupwayi, N. Z., Rice, W. A., and Clayton, G. W.: Soil microbial diversity and community structure under wheat as influenced by tillage and crop rotation, Soil Biol. Biochem., 30, 1733–1741, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0038-0717(98)00025-X, 1998.

Mazzola, M. and Freilich, S.: Prospects for Biological Soilborne Disease Control: Application of Indigenous Versus Synthetic Microbiomes, Phytopathology, 107, 256, https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-09-16-0330-RVW, 2017.

Mendes, L. W., Kuramae, E. E., Navarrete, A. A., Veen, J. V., and Tsai, S. M.: Taxonomical and functional microbial community selection in soybean rhizosphere, ISME J., 8, 1577–1587, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2014.17, 2014.

Mona, N., Högberg., Stephanie, A., Yarwood., and David, D., Myrold.: Fungal but not bacterial soil communities recover after termination of decadal nitrogen additions to boreal forest, Soil Biol. Biochem., 2014, 35–43, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.01.014, 2014.

Nel, B., Steinberg, C., Labuschagne, N., and Viljoen, A.: Evaluation of fungicides and sterilants for potential application in the management of Fusarium wilt of banana, Crop. Prot., 26, 697–705, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2006.06.008, 2007.

Pauline, D., Soraya, C. F., A., Olinto, L., Irene, C., Stefaan, D., Jane, D., and Monica, H.: Disease suppressiveness to Fusarium wilt of banana in an agroforestry system: Influence of soil characteristics and plant community, Agric., Ecosyst. Environ., 239, 173–181, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2017.01.018, 2017.

Ploetz, R. C.: Fusarium Wilt of Banana, Phytopathology., 105, 15121521, https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-04-15-0101-RVW, 2015.

Qiu, M., Zhang, R., Xue, C., Zhang, S., Li, S., Zhang, N., and Shen, Q.: Application of bio-organic fertilizer can control Fusarium wilt of cucumber plants by regulating microbial community of rhizosphere soil, Biol. Fertil. Soils., 48, 807–816, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-012-0675-4, 2012.

Robert, P. L. and Halloran, J. M.: Management Effects of Disease-Suppressive Rotation Crops on Potato Yield and Soilborne Disease and Their Economic Implications in Potato Production, Am J Potato Res., 91, 429–439, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12230-014-9366-z, 2014.

Schloss, P., Westcott, S., Ryabin, T., Hall, J., Hartmann, M., Hollister, E., Lesniewski, R., Oakley, B., Parks, D., Robinson, C., Sahl, J., Stres, B., Thallinger, G., Van Horn, D., and Weber, C.: Introducing mothur: Open-Source, Platform-Independent, Community-Supported Software for Describing and Comparing Microbial Communities, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 75, 7537–7541, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01541-09, 2009.

Schoch, C. L., Seifert, K. A., Huhndorf, S., Robert, V., Spouge, J. L., Levesque, C. A., and Chen, W.: Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 109, 6241–6246, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1117018109, 2012.

Shen, C., Xiong, J., Zhang, H., Feng, Y., Lin, X., Li, X., Liang, W., and Chu, H.: Soil pH drives the spatial distribution of bacterial communities along elevation on Changbai Mountain, Soil Biol. Biochem., 57, 204–211, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.07.013, 2013.

Shen, Z., Ruan, Y., Xue, C., Zhang, J., and Li, R.: Rhizosphere microbial community manipulated by 2 years of consecutive biofertilizer application associated with banana Fusarium wilt disease suppression, Biol. Fertil. Soil., 51, 553–562, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-015-1002-7, 2015.

Shen, Z., Xue, C., Taylor, P., Ou, Y., Wang, B., Zhao, Y., Ruan, Y., Li, R., and Shen, Q.: Soil pre-fumigation could effectively improve the disease suppressiveness of biofertilizer to banana Fusarium wilt disease by reshaping the soil microbiome, Biol. Fertil. Soil., 54, 793–806, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-018-1303-8, 2018.

Sun, R., Zhang, X. X., Guo, X., Wang, D., and Chu, H.: Bacterial diversity in soils subjected to long-term chemical fertilization can be more stably maintained with the addition of livestock manure than wheat straw, Soil Biol. Biochem., 88, 9–18, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.05.007, 2015.

Trivedi, P., Delgado-Baquerizo, M., Trivedi, C., Hamonts, K., Anderson, I. C., and Singh, B. K.: Keystone microbial taxa regulate the invasion of a fungal pathogen in agro-ecosystems, Soil Biol. Biochem., 111, 10–14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.03.013, 2017.

Wang, B., Yuan, J., Zhang, J., Shen, Z., Zhang, M., Li, R., Ruan, Y., and Shen, Q.: Effects of novel bioorganic fertilizer produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens W19 on antagonism of Fusarium wilt of banana, Biol. Fertil. Soil., 49, 435–446, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-012-0739-5, 2013.

Wang, B., Li, R., Ruan, Y., Ou, Y., and Zhao, Y.: Pineapple–banana rotation reduced the amount of Fusarium oxysporum more than maize–banana rotation mainly through modulating fungal communities, Soil Biol. Biochem., 86, 77–86, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.02.021, 2015.

Wang, B., Sun, M., Yang, J., Shen, Z., Ou, Y., Fu, L., Zhao, Y., Li, R., Ruan, Y., and Shen, Q.: Inducing banana Fusarium wilt disease suppression through soil microbiome reshaping by pineapplebanana rotation combined with biofertilizer application, NCBI Sequence Read Archive database: SRP234066, [data set], https://trace.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/sra/?study=SRP234066, last access: 23 December 2021.

Wang, Q., Garrity, G. M., Tiedje, J. M., and Cole, J. R.: Nave Bayesian Classifier for Rapid Assignment of rRNA Sequences into the New Bacterial Taxonomy, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 73, 5261, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00062-07, 2007.

Xiong, W., Zhao, Q., Xue, C., Xun, W., Zhao, J., Wu, H., Rong, L., and Shen, Q.: Comparison of Fungal Community in Black Pepper-Vanilla and Vanilla Monoculture Systems Associated with Vanilla Fusarium Wilt Disease, Front. Microbiol., 7, 117, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00117, 2016.

Xiong, W., Li, R., Ren, Y., Liu, C., Zhao, Q., Wu, H., Jousset, A., and Shen, Q.: Distinct roles for soil fungal and bacterial communities associated with the suppression of vanilla Fusarium wilt disease, Soil Biol. Biochem., 107, 198–207, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.01.010, 2017.

Yin, W., Jie, X., Shen, J., Luo, Y., Scheu, S., and Xin, K.: Tillage, residue burning and crop rotation alter soil fungal community and water-stable aggregation in arable fields, Soil Till Res., 107, 71–79, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2010.02.008, 2010.

Zhang, F., Zhen, Z., Yang, X., Wei, R., and Shen, Q.: Trichoderma harzianum T-E5 significantly affects cucumber root exudates and fungal community in the cucumber rhizosphere, Appl. Soil Ecol., 72, 41–48, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2013.05.016, 2013a.

Zhang, H., Mallik, A., and Zeng, R. S.: Control of Panama Disease of Banana by Rotating and Intercropping with Chinese Chive (Allium Tuberosum Rottler): Role of Plant Volatiles, J. Chem. Ecol., 39, 243–252, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-013-0243-x, 2013b.

Zhou, J., Deng, Y., Luo, F., He, Z., and Yang, Y.: Phylogenetic Molecular Ecological Network of Soil Microbial Communities in Response to Elevated CO2, mBio., 2, 4, https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00122-11, 2011.