the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Pairing litter decomposition with microbial community structures using the Tea Bag Index (TBI)

Anne Daebeler

Eva Petrová

Elena Kinz

Susanne Grausenburger

Helene Berthold

Taru Sandén

Including information about soil microbial communities into global decomposition models is critical for predicting and understanding how ecosystem functions may shift in response to global change. Here we combined a standardised litter bag method for estimating decomposition rates, the Tea Bag Index (TBI), with high-throughput sequencing of the microbial communities colonising the plant litter in the bags. Together with students of the Federal College for Viticulture and Fruit Growing, Klosterneuburg, Austria, acting as citizen scientists, we used this approach to investigate the diversity of prokaryotes and fungi-colonising recalcitrant (rooibos) and labile (green tea) plant litter buried in three different soil types and during four seasons with the aim of (i) comparing litter decomposition (decomposition rates (k) and stabilisation factors (S)) between soil types and seasons, (ii) comparing the microbial communities colonising labile and recalcitrant plant litter between soil types and seasons, and (iii) correlating microbial diversity and taxa relative abundance patterns of colonisers with litter decomposition rates (k) and stabilisation factors (S). Stabilisation factor (S), but not decomposition rate (k), correlated with the season and was significantly lower in the summer, indicating a decomposition of a larger fraction of the organic material during the warm months. This finding highlights the necessity to include colder seasons in the efforts of determining decomposition dynamics in order to quantify nutrient cycling in soils accurately. With our approach, we further showed selective colonisation of plant litter by fungal and prokaryotic taxa sourced from the soil. The community structures of these microbial colonisers differed most profoundly between summer and winter, and selective enrichment of microbial orders on either rooibos or green tea hinted at indicator taxa specialised for the primary degradation of recalcitrant or labile organic matter, respectively. Our results collectively demonstrate the importance of analysing decomposition dynamics over multiple seasons and further testify to the potential of the microbiome-resolved TBI to identify the active component of the microbial community associated with litter decomposition.

This work demonstrates the power of the microbiome-resolved TBI to give a holistic description of the litter decomposition process in soils.

- Article

(3375 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(3670 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Litter decomposition is one of the most important terrestrial ecosystem functions. Soil microorganisms drive this process by breaking down plant material, leading to the release of carbon into the atmosphere as CO2 or into the soil, where it either gets sequestered or further degraded (Talbot and Treseder, 2011; Allison et al., 2013; Cotrufo et al., 2013). Other factors governing litter decomposition include the molecular structure of the litter, its physical (dis)connection from the decomposer community, and its organo–mineral associations (Schmidt et al., 2011). Litter decomposition, therefore, directly affects both Earth's atmosphere and soil health. Understanding this process holds the key to better agricultural management, mitigating greenhouse gas emissions, and predicting future soil carbon storage levels. However, because of the processes' complexity and our inadequate understanding of how biodiversity affects it, the application of the litter decomposition process to agricultural practices and global decomposition models is not performing currently at its full potential. Seasonality, mainly through temperature and moisture effects, has been demonstrated to affect litter decomposition directly and indirectly (Prescott, 2010). Direct effects occur due to the high sensitivity of biological processes to temperature and water availability, and indirect effects may be the consequence of phenotypic or community shift responses of the soil biota. Soil microbial community structure has been hypothesised to influence process rates in soils (McGuire and Treseder, 2010; Graham et al., 2016). In a few models that linked microbial diversity and decomposition (e.g. MIMICS, Wieder et al., 2014, and MEMS, Cotrufo et al., 2013), microbial diversity positively affected nutrient-cycling efficiency and ecosystem processes through either greater intensity of microbial exploitation of organic matter or functional niche complementarity.

Litter quality has been shown to be important for microbial community structure since both bacteria and fungi respond to litter physicochemical changes during the decay process (Aneja et al., 2006; Purahong et al., 2016). Litter biochemical traits, such as the ratio and the fraction of lignin, are considered good indicators of litter quality, as they are related to nutrient availability and decomposition stage (Prescott, 2010; Talbot and Treseder, 2012). Different litter types can thus select microbial taxa that are more specialised in degrading their components. Fungi are known to produce a suite of oxidative enzymes that degrade the recalcitrant biopolymers of litter (Mathieu et al., 2013; Hoppe et al., 2015). In contrast, only a few types of bacteria degrade all lignocellulosic polymers, while most typically target simple soluble compounds (de Boer and van der Wal, 2008). Therefore, the role of bacteria in the decomposition of more recalcitrant material is still debated (Wilhelm et al., 2019). However, still little is known on how microbial communities specialise in litter types with different physical and chemical traits (Freschet et al., 2011; Pioli et al., 2020).

The community structure and functioning of microbial communities are further affected by biotic interactions (Daebeler et al., 2014; Garbeva et al., 2014; Ho et al., 2016; Wilpiszeski et al., 2019). In natural communities, such interactions generally involve competition for space and resources (Boddy, 2000, and Faust and Raes, 2012, and references therein) but may also be mutualistic. For example, it has been suggested that bacteria can facilitate the activity of decaying fungi by providing important nutrients such as nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) (Purahong et al., 2016). Likewise, fungi have been demonstrated to help improve the accessibility of litter for bacteria (de Boer et al., 2005). Therefore, it is likely that decomposition dynamics depend not only on microbial community structure, but also on the facilitative or competitive interactions among microbial species (Liang et al., 2017; Aleklett et al., 2021). Despite the indications of the high importance of species interactions for soil organic matter decomposition dynamics, they are not well understood, and more studies under natural conditions are needed.

Linking microbial diversity to function across different environments represents a key aspect of ecology. In this study, we used high-throughput sequencing in combination with the Tea Bag Index (TBI) – a cost-effective method to study litter decomposition using commercially available teabags (Keuskamp et al., 2013). This combination of methods allows insight to be gained into the effect of litter traits on the community structure of microbial decomposers and soil organic matter decomposition rates to be linked with microbial population dynamics. The microbial diversity in soils is immense (Thompson et al., 2017); yet large parts of it are dormant (Lennon and Jones, 2011) or simply do not participate in litter degradation (Falkowski et al., 2008). Therefore, the buried teabags used in this study serve as “traps” for microbial litter degraders and assure that the diversity we observe is composed only of its active litter degrading and associated taxa.

Specifically, in this citizen-science-aided project, we used barcoded-amplicon high-throughput sequencing of the SSU rRNA gene (for bacteria and archaea) and the internal transcribed spacer region (ITS) for fungi to compare the microbial community structure in two different standardised litter types (rooibos and green tea) with the microbial community in three different local soil types and during four seasons, over the course of a year. We tested the extent to which litter types with different traits represent selective substrates for microbial community colonisation. Finally, we related the microbial diversity and species relative abundance patterns with two proxies (decomposition rate (k) and stabilisation factor (S)) that describe the decomposition of labile material (Keuskamp et al., 2013). We generally assumed that litter decomposition dynamics and soil microbial communities will differ between the seasons. Soil types were expected to be similar to each other given the small, geographic scale and given that management practices are the same. More specifically we hypothesised that (i) microbial diversity in the teabags will correlate positively with decomposition rates and negatively with stabilisation factors and that (ii) different subsets of local soil microbiota will colonise labile and more recalcitrant litters, and thus each litter type will select a different, specialised community. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study utilising the Tea Bag Index method in combination with a microbiome analysis to investigate how litter decomposition is linked with microbial community structure and diversity.

2.1 Description of the study sites

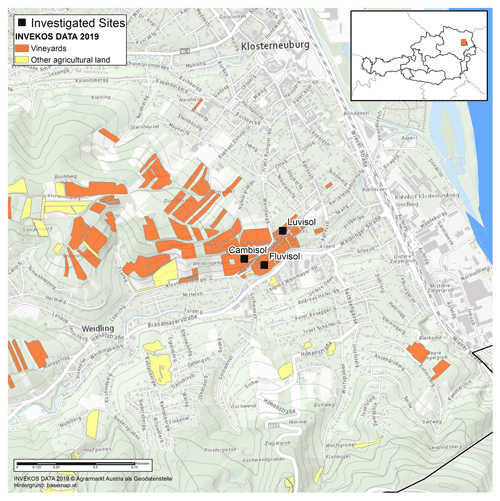

The study site is located at the Agneshof vineyards of the agricultural college for Viticulture and Pomology in Klosterneuburg, just north of Vienna, Austria (Fig. 1). The mean annual temperature was 11.1 ∘C, and the mean total annual precipitation was 689 mm between 2010 and 2019 at the Agneshof weather station. We selected three study plots with three different soil types, Fluvisol, Cambisol, and Luvisol (Anjos et al., 2015), to maximise the difference in soil characteristics. The Fluvisol and Luvisol sites were cultivated with wine, whereas the Cambisol site was a set-aside grassland between vineyards. At Fluvisol and Luvisol sites, we selected one inter-row sampling area in the middle of the vineyard at least 5 m distance from the vineyard edge. In contrast, at the Cambisol, we selected a sampling area that was at least 5 m distance from the neighbouring vineyard.

Figure 1Geographical map of the investigated sites in Klosterneuburg, Austria. The study sites are marked by black squares. © INVEKOS DATA 2019. Agrarmarkt Austria als Geodatenstelle. Background: https://basemap.at (last access: 9 February 2021).

2.2 Soil sampling and soil chemical analyses

Composite soil samples of 10–12 individual soil cores were taken from 0–10 cm depth in two (winter and spring) or three (summer and autumn) field replicates every 3 months between March 2018 and December 2018 to characterise the sites. Soils were sieved through a 2 mm stainless sieve and air-dried prior to further analyses. Soil pH was measured electrochemically (pH/mV Pocket Meter pH 340i, WTW) in 0.01 M CaCl2 at a soil-to-solution ratio of 1 : 5 (ÖNORM L1083). Plant-available phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) were determined by calcium–acetate–lactate (CAL) extraction (ÖNORM L1087). Total soil organic C concentrations of the soil samples were analysed by dry combustion in a LECO RC-612 TruMac CN at 650 ∘C (ÖNORM L1080; LECO Corp.). Total N was determined according to ÖNORM L1095 with elemental analysis using a CNS (carbon, nitrogen, sulfur) 2000 SGA-410–06 at 1250 ∘C. KMnO4 determination of labile carbon was analysed according to Tatzber et al. (2015). Potential nitrogen mineralisation was measured by the anaerobic incubation method (Keeney, 1982), as modified according to Kandeler (1993). The soil texture was determined according to ÖNORM L1061-1 and L1062-2. For testing statistical differences in the chemical parameters between plots, samples from different seasons were pooled.

2.3 Tea Bag Index (TBI)

The Tea Bag Index (i.e. the decomposition rate (k) and stabilisation factor (S)) was assessed according to Keuskamp et al. (2013) between December 2017 and December 2018. In short, commercially available green tea (EAN 87 22700 05552 5) and rooibos tea (EAN 87 22700 18843 8) in non-woven, polypropylene mesh bags produced by Lipton (Unilever) were used as standardised litter bags. Green and rooibos teabags in eight replicate pairs (four replicate pairs for calculating the TBI parameters and four replicate pairs for molecular analysis) were weighed and buried pairwise at a depth of 8 cm for 3 months (Winter: December 2017–March 2018, spring: March 2018–June 2018, summer: June 2018–September 2018, autumn: September 2018–December 2018). There was a 15 cm distance between the green and rooibos teabags within a replicate pair and at least 75 cm between the replicate pairs. Subsequently, the teabags used for calculating the TBI were retrieved, cleaned of adhering soil particles, and dried for at least 3 d on a warm, dry location before reweighing. Values for k and S were calculated using the mass losses of green and rooibos teas, as described in Keuskamp et al. (2013). The teabags used for molecular analysis were frozen on-site on dry ice after being dug out and cleaned and transported in a frozen state to the Anaerobic and Molecular Microbiology lab at SoWa, BC CAS, České Budějovice, Czechia, for further analysis.

3.1 DNA extraction and amplicon sequencing

DNA was extracted from 0.25 g of frozen tea material or soil using the DNeasy PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Amplicon sequencing was done using a two-step barcoding approach (Naqib et al., 2019). DNA was also extracted from two unburied green tea and rooibos teabags to estimate the microbial load and diversity already present on the tea material. The DNA extracts were then quantified using a Quant-iT™ PicoGreen™ dsDNA Assay Kit (Thermo) and diluted to 10 ng µL−1 for use as templates for PCR amplification. The V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene (16S hereafter) was amplified using primers 515F-mod-CS1 (aca ctg acg aca tgg ttc tac aGT GYC AGC MGC CGC GGT AA) and 806-mod-CS2 (tacggtagcagagacttggtctGGACTACNVGGGTWTCTAAT; Walters et al., 2016) while ITS was amplified using primers ITS1f-CS1 (acactgacgacatggttctacaCTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA) and ITS2-CS2 (tacggtagcagagacttggtctGCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC; Gardes and Bruns, 1993). Amplification was done in a T100 thermal cycler (Biorad) with amplification cycles ranging from 25 to 28 for 16S and 29 to 32 cycles for ITS, depending on the amount of template. The full protocol is available online (Angel, 2021). Before processing the samples from the experiment, we performed a preliminary test using the chloroplast blocker pPNA (PNA Bio). For this purpose, DNA from the unburied teabags, two buried teabags, and a soil sample was used for amplification with or without PNA (0.25 µM, final conc.). If PNA was used, an additional PCR step of PNA clamping (75 ∘C for 10 s) was added in each cycle between the denaturation and primer annealing step, according to the manufacturer's instructions. In addition, no-template PCR control (NTC) and “blank extraction control” (DNA extraction and amplification without a sample) were sequenced in each batch (season). A mock community (ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community DNA Standard II; Zymo Research) was also amplified and sequenced. Library construction and sequencing were performed at the DNA Services Facility at the University of Illinois, Chicago, using an Illumina MiniSeq sequencer (Illumina) in the 2×250 cycle configuration (V2 reagent kit).

3.2 Sequence data processing and classification

Primer regions were trimmed off the amplicon sequence data using cutadapt (V2.3; Martin, 2011). Downstream sequencing processing steps were done in R (V4.0.3; R Core Team, 2020). Quality trimming and clustering into amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were done using the DADA2 pipeline (Callahan et al., 2016). For 16S, the following quality filtering options were used: no truncate, maxN = 0, maxEE = c(2, 2), and truncQ = 2. For ITS, the following options were used: minLen = 50, maxN = 0, maxEE = c(2, 2), and truncQ = 2. Chimera sequences were removed with removeBimeraDenovo() using the “consensus” method “allowOneOff”. Taxonomic classification of the 16S ASVs was done with assignTaxonomy() against the SILVA database (Ref NR 99; V138.1; Quast et al., 2012), while for ITS, it was done against the UNTIE database (Nilsson et al., 2018). Potential contaminant ASVs were removed using decontam (Davis et al., 2018), employing the default options. Unclassified taxa and those classified as either “eukaryota”, “chloroplast”, or “mitochondria” (in the 16S dataset) or as “bacteria” or “archaea” (in the ITS dataset) were removed. In addition, for beta-diversity analysis, ASVs, appearing in <5 % of the samples, were removed.

3.3 Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed in R (V4.0.3; R Core Team, 2020). Significant differences between the decomposition rates (k), stabilisation factors (S), and the chemical parameters were determined using ANOVA followed Tukey's HSD on the estimated marginal means (Lenth, 2021), functions emmeans() and contrast()). To increase the statistical power, samples from different seasons were pooled for testing the differences in soil parameters. Spearman rank (ρ) correlations were performed to investigate the relationship between soil properties and the decomposition rates, stabilisation factors, and microbial amplicon sequence variant (ASV) richness and diversity. Sequence data handling and manipulation were done using the phyloseq package (McMurdie and Holmes, 2013). For alpha-diversity analysis, all samples were subsampled (rarefied) to the minimum sample size using a bootstrap subsampling with 1000 iterations to account for library size differences, while for beta-diversity analysis, library size normalisation was done by converting the data to relative abundance and multiplying by median sequencing depth. The inverse Simpson index, the Shannon H diversity index, and the Berger–Parker dominance index were calculated using the function EstimateR() in the vegan package (Oksanen et al., 2018) and tested using ANOVA in the stats package, followed by a post hoc Tukey HSD test on the estimated marginal means. Variance partitioning and testing were done using the PERMANOVA (Mcardle and Anderson, 2001) function adonis() using Horn–Morisita distances (Horn, 1966). Differences in order composition between the soil or litter types were tested similarly to STAMP (Parks et al., 2014) but written in R. Briefly, the relative abundance of the orders was compared between samples using the Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test (kruskal.test() in the stats package), followed by the Mann–Whitney post hoc test (wilcox.test() in the stats package), and false discovery rate (FDR) corrected using the Benjamini–Hochberg method (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995); p.adjust() in the stats package). Differentially abundant ASVs were detected using ALDEx2 (Fernandes et al., 2013) using the option denom = iqlr for the aldex.clr() function. Differences in composition between the two teabag types and the soil were tested in a pairwise manner. Plots were generated using ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016).

4.1 Soil chemical characteristics and Tea Bag Index

The weather during the study was typical for the region, with mean seasonal air temperatures ranging from 2 ∘C in the winter to 22.5 ∘C in the summer and most of the rain occurring summer and autumn (Table S1 in the Supplement).

To be able to draw conclusions about the connections between the community structures of microbial litter decomposers, litter types, and the decomposition process, we first determined the basic soil characteristics of the three study plots. The Luvisol plot exhibited the lowest contents of P, K, TOC, and sand and the highest pH (Table S2).

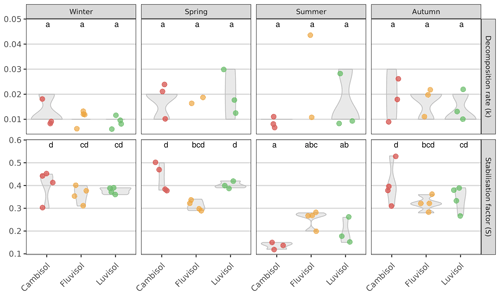

Next, we determined the decomposition rate, k (which reflects the rate by which the labile fraction of the litter is decomposed), and the stabilisation factor, S (which reflects the proportion of non-decomposed, hydrolysable labile fraction that is remaining after the incubation), for all three study plots and during four seasons. Despite decomposition rates ranging from 0.008 d−1 at the Cambisol site to 0.025 d−1 at the Fluvisol site (in the summer), no significant differences could be found between sites or seasons, neither when pooled (P=0.15), nor at each site (P=0.45; Fig. 2). The results are well within the range of summer data previously reported from Austria (Buchholz et al., 2017; Keuskamp et al., 2013; Sandén et al., 2020, 2021). However, to the best of our knowledge, we are the first ones to report data during four seasons. There was also no correlation of any measured soil properties with the decomposition rates (data not shown), as also reported in Sandén et al. (2020). These results were surprising, given the differences in the determined soil characteristics (Table S2) and temperature between the seasons, and point to the possibility that micro conditions in the soil play a larger role than expected in determining decomposition rates.

Figure 2Decomposition rate (k) and stabilisation factor (S) determined at three sites with different soil types during four seasons. Values shown are averages (n=4, lower in case a teabag broke during incubation or in case the rooibos was not in the first phase of decomposition anymore and the main assumptions for calculation of k were violated; thus, k could not be calculated) and the interquartile range (violin shapes). Lowercase letters indicate significant differences between samples (seasons and sites together; padjusted≤0.05).

The stabilisation factors in general were higher than presented in Keuskamp et al. (2013); however, this is the first time that the stabilisation factors are presented for different seasons, and it seems logical that the S would be higher in the colder seasons than over the summer. The summer values are well in agreement with Keuskamp et al. (2013) and the other seasons with Sarneel et al. (2020) from tundra environments and Sandén et al. (2021) from urban Austrian sites that both reported stabilisation factors up to 0.4, which gives further support for our findings. We did, however, observe significantly lower stabilisation factors in summer than in all other seasons (padjusted≤0.001). Specifically, the stabilisation factors determined at the Cambisol and Luvisol sites were significantly lower in summer than those determined for the other three seasons (padjusted≤0.05). These results indicate that the conditions during the summer months favour the decomposition of a larger fraction of the organic material but not necessarily in a faster manner. This is in apparent contrast to the well-known relationship between temperature and decomposition rates (see Kirschbaum, 1995, and references therein). However, one should consider that (1) temperature sensitivity of the decomposition rate is much higher at low temperature and that (2) the decomposition rate is also heavily affected by moisture, which could counterbalance the effect of temperature. Similarly, Elumeeva et al. (2018) also found a correlation of S but not of k to various edaphic factors. Notably, soil moisture, pH, and altitude did not affect k (but were correlated with S). Since S measures “how much” (rather than “how fast”) of the labile litter fraction is stabilised material is remaining after incubation, it can be assumed that S is more sensitive than k to the composition of microbial communities that are active at the time of decomposition. This is because the underlying processes amounting to S involve the concerted (discrete) action of several microbial guilds, each specialising in decomposing one or more substrates sequentially (Zheng et al., 2021; Glassman et al., 2018).

4.2 Establishment of an amplicon sequencing protocol to be used with the TBI

Before investigating the microbial communities colonising the teabags, we extracted DNA from unburied teabags serving as negative controls and performed rRNA gene amplicon sequencing (16S and ITS regions). DNA yields were similar between buried and the unburied teabags and averaged 6.1±12.9 and 23.0±14.0 mg g−1, probably because, as expected, most of the DNA originated from the plant cells (data not shown). A preliminary study using the chloroplast blocker pPNA was carried out to estimate the effect of plant chloroplast on the sequencing output (what proportion of the sequences is dominated by chloroplasts). As Table S3 shows, only the unburied tea material had a significant portion of chloroplast reads (64.5 % and 15.4 % for green tea and rooibos, respectively), while after 3 months in the ground, no chloroplast reads were detected (most likely due to a combination of microbial colonisation and chloroplast DNA degradation). Using the pPNA blocker nearly eliminated the number of chloroplast reads while at the same time not biasing the community composition in the samples (Fig. S1 in the Supplement). Nevertheless, since chloroplasts were undetected in the buried teabags, pPNA was not used in subsequent sample processing. Figure S1 also shows that, as expected, the microbial load on the unburied tea material was minimal and yielded only about 5 % of the reads after quality filtering. Such a low microbial load is expected for above-ground plant parts (e.g. Chen et al., 2020; Knorr et al., 2019).

To then study the prokaryotic and fungal communities potentially associated with litter degradation, we extracted DNA from soil and triplicate rooibos and green tea teabags buried for 3 months for each season at each site and performed rRNA gene amplicon sequencing.

4.3 Richness and diversity of prokaryotic and fungal communities in teabags and soils

Sequencing the prokaryotic 16S rRNA gene and the fungal ITS region and downstream data processing yielded a total of 16 100 16S ASVs and 3685 ITS ASVs. After removing all ASVs with a prevalence of <5 % of the samples, 4217 16S ASVs and 402 ITS ASVs remained. As expected, archaea were rare and comprised only about 0.9 % of the reads. At all three sites, the observed prokaryotic and fungal ASV richness (i.e. the observed number of prokaryotic and fungal ASVs) was roughly twice as high in the soil samples than in teabag samples (Fig. S2). Likewise, the microbial diversity, as estimated by the inverse Simpson, Shannon, and Berger–Parker indexes, was generally significantly higher in the soil samples than in the teabag samples. There was, however, no significant difference between rooibos and green teabags in terms of prokaryotic and fungal ASV richness or diversity. These findings indicate selective microbial colonisation of both the labile and the more recalcitrant litter sourced from the surrounding soil during all seasons.

Both the Fluvisol and the Cambisol site teabags buried in summer harboured a significantly richer prokaryotic community than those buried in other seasons. Such seasonal differences were not observed with the fungal communities. Similar to the observed differences in richness, the biodiversity of prokaryotic communities detected in the teabags was often significantly higher in summer samples than in all other seasons. This hints that there are more distinct prokaryotic species capable of colonising and degrading litter in summer than in the other seasons. An explanation for this observation could be the activation of decomposing prokaryotic soil populations by summer conditions such as elevated temperature (Kirschbaum, 1995; Allison et al., 2010). Finally, the prokaryotic ASV richness and diversity of the communities that colonised the teabags were negatively correlated with the stabilisation factor S (p<0.01; correlation factor and p<0.01; correlation factor , respectively). These findings suggest that less inhibition of litter decomposition occurred in the summer season, in which richer and more diverse prokaryotic communities were associated with the degradation. With these data, we can partially confirm our hypothesis of a positive correlation between microbial diversity and litter decomposition. Possibly, a positive relationship between microbial diversity and litter decomposition is prevalent in many soil types, as it has also been experimentally established in a Cambisol (Maron et al., 2018).

The richness and diversity of fungal ASVs were generally comparable across the seasons at all sites, except for a higher richness at the Cambisol site in winter compared to the other seasons. This could be explained by the hyphae growth form of many fungi, which allows them to span various microsites in the heterogeneous soil environment and makes them less sensitive to chemical gradients and seasonal changes (Yuste et al., 2010).

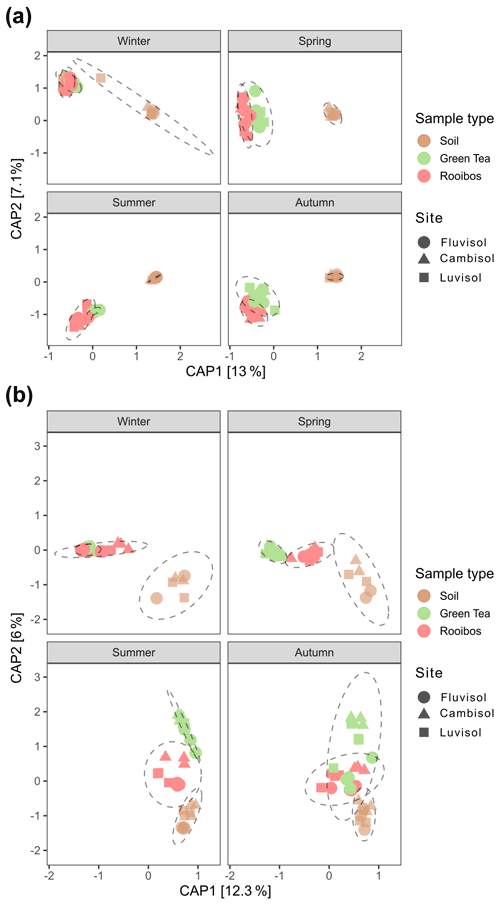

4.4 Selective colonisation of teabags by prokaryotic and fungal soil populations

After 3 months of burial, the community structures of prokaryotes and fungi detected in teabags were significantly different from those detected in soil (Table S4, Fig. 3). Moreover, the differential abundance analysis clearly showed enrichment of about a third of the 16S ASVs and 14 %–20 % of the ITS ASVs in the teabags compared to the soil (Fig. S4). Therefore, as has been observed before in various soil systems and with a range of different litter types (Aneja et al., 2006; Bray et al., 2012; Albright and Martiny, 2018; Yan et al., 2018; Wei et al., 2020), we conclude that the litter material in the teabags selected for colonisation by a sizeable portion of the bacterial, archaeal, and fungal population acting as the active litter decomposers and associated populations. While fungi colonise new patches using hyphal growth, prokaryotes depend on mechanisms such as adhesion to hyphae, motility, or passive diffusion in water. Interestingly, Albright et al. (2019) have shown that unicellular bacteria and fungi do not differ in their dispersal abilities. Successful colonisation of the teabags is related to microbial traits such as growth rate, mobility, and adhesive and competitive ability (Albright and Martiny, 2018) and does not exclusively indicate the degrading ability of a microbe. The results presented here therefore may be biased towards the more fast-growing, strong competitors which disperse easily and may overlook contributions of slower degraders in soil. Comparing the green tea with the rooibos samples, we could detect a subgroup of ca. 4.2 % and 2.5 % of the 16S rRNA gene ASVs that preferentially colonised either the green tea or rooibos teabags. In contrast, only four ITS ASVs differed between the green tea and rooibos samples, indicating non-preferential colonisation. For both prokaryotes and fungi, soil or litter type explained the largest fraction of the variance in the community composition (38 % and 23 %, respectively; Table S4), although, not surprisingly, this was driven mainly by the differences between soil and teabag communities. However, the difference between green tea and rooibos was not negligible and explained 13 % and 9 % of the variance in a pairwise comparison for prokaryotes and fungi, respectively (Table S4, Fig. 3). The season was also a major factor, explaining 20 % and 22 % of the variance, respectively, and driven mostly by the difference between summer and winter (27 % and 29 % of the variance, respectively; Table S4, Fig. S4). In contrast, soil type had only little effect, explaining only 3 % and 5 % of the variance, respectively. This contrasts with the recent findings of Pioli et al. (2020), in which a large effect of soil type on the community composition was reported, though this is not surprising considering that this study was performed on a very local scale, with identical climate and similar soil types and management practices.

Figure 3Principal coordinate analyses plots of prokaryotic (a) and fungal (b) community compositions based on Morisita–Horn distances of 16S rRNA gene and ITS region ASVs derived from soil, green tea, and rooibos teabags. The models were obtained using the formula: distance matrix ∼ field + sample type × season.

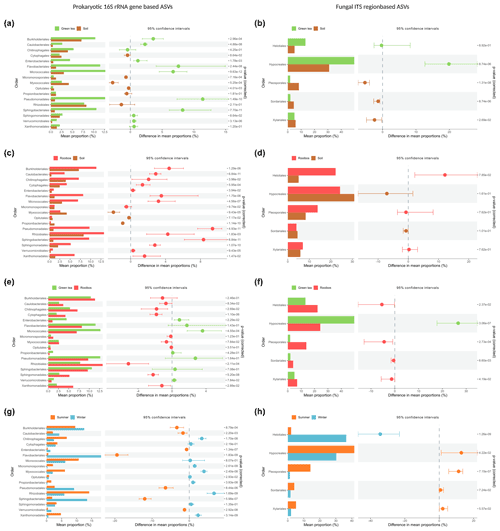

Further interested in the identity and possible colonisation preferences of the microbial decomposers, we compared the relative abundance of dominant orders between the different teabags and the soil types and between the teabag communities in the summer vs winter, in a pairwise manner. This analysis allowed us to identify specific bacterial and fungal lineages that exhibited distinct colonisation patterns and were enriched in samples from the more labile green tea or the more recalcitrant rooibos bags. In contrast to our hypothesis (different litter types will select different microbial colonisers), many of the detected microbes were either equally selected or deselected by both tea types.

Most strikingly, members of the Pseudomonadales and Sphingobacteriales were the most enriched in both green tea and rooibos teabags as compared to the soil from the same sites with differences of 11.4 % and 9.4 % for Pseudomonadales and 8.2 % and 8.3 % for Sphingobacteriales, respectively (Fig. 4a, c). Additionally, Flavobacteriales, Micrococcales, and Burkholderiales also showed higher relative abundances than the surrounding soil (Fig. 4a). Similar increases in relative abundance of Pseudomonadales, Flavobacteriales, Sphingobacteriales, and Micrococcales have been observed in straw decomposing soil microcosms (Jiménez et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2020). Members of Pseudomonadales, Flavobacteriales, and Rhizobiales are well known to have the capacity to degrade plant lignin, (hemi-)cellulose, or carboxymethyl cellulose (Koga et al., 1999; McBride et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2013; Talia et al., 2012; Jackson et al., 2017). Furthermore, Pseudomonadales and Flavobacteriales can be involved in the degradation of furanic compounds (Jiménez et al., 2013; López et al., 2004). The increased presence of Sphingobacteriales may be explained by their capability to produce β-glucosidases that remove the cello-oligosaccharides produced by polymer degraders (Matsuyama et al., 2008) and is considered a critical and rate-limiting step in cellulose degradation (du Plessis et al., 2009). Indeed, soils with high β-glucosidase activity were also found to be dominated by members of the Sphingobacteriales (particularly from the Chitinophagaceae family; Bailey et al., 2013). Merely the bacterial orders Cytophagales, Enterobacteriales, and Rhizobiales exhibited relative abundance patterns indicative of a selection only by rooibos or green tea, as we hypothesised (Fig. 4a, c).

Figure 4Comparative analysis of the relative abundance based on bacterial and fungal order profiles between soil or litter types and seasons. Samples were compared using Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test, followed by the Mann–Whitney post hoc test, and FDR-corrected using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. Only orders with a median relative abundance of >5 % are shown.

We further observed significant, selective enrichments of fungal orders in both teabag types. Members of the Hypocreales had a 20 % higher relative abundance in green tea than in soil but were not enriched in the rooibos teabags (Fig. 4b). In contrast, Helotiales were only enriched in rooibos teabags by 12 % (Fig. 4d). Hypocreales are common saprophytic fungi and are known to produce cellobiohydrolases and endoglucanases necessary for the depolymerisation of celluloses (Lynd et al., 2002; Martinez et al., 2008). Helotiales are abundant, cellulolytic soil fungi that have been shown to specialise in degrading recalcitrant organic carbon (Newsham et al., 2018; MGnify, 2020). Our findings could point towards members of the exclusively enriched orders being specialised primary degraders of either labile of recalcitrant organic matter and not associated scavengers of degradation products. Since the green tea litter contains a higher hydrolysable fraction and a lower C : N ratio (Keuskamp et al., 2013), we assume the Enterobacteriales and Hypocreales, which were exclusively enriched in green tea samples, were involved in the degradation of more labile compounds such as cellulose. Cytophagales, Rhizobiales, and Helotiales, which were exclusively selected by rooibos tea on the other hand, may be important primary degraders of more recalcitrant organic matter. Members of these five orders could therefore possibly serve as indicator species in future decomposition studies.

In contrast to our expectations, the different seasons did not display different litter decomposition rates, but they did differ in the extent to which the hydrolysable litter fraction was degraded. At the same time, microbial richness and diversity of litter-colonising degraders were positively correlated with the fraction of degraded organic carbon, indicating a positive relationship between litter degradation and microbial biodiversity in soil. Microbial colonisation of the tea litter was substrate-selective and season-dependent for prokaryotes and fungi. On average, about 28 %–30 % of the prokaryotic ASVs and 14 %–19 % of the fungal ASVs preferentially colonised the rooibos and green tea, respectively. However, their exact identity varied between seasons, especially between the summer and winter. A total of five microbial orders were identified as possible indicator species through their exclusive colonisation of either recalcitrant (rooibos) or labile (green tea) litter. This work demonstrates the power of the microbiome-resolved TBI to give a holistic description of the litter decomposition process in soils.

The scripts to reproduce this and all downstream statistical analysis steps are available online under https://github.com/roey-angel/TeaTime4Schools (last access: 9 March 2022) and https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6340082 (Angel, 2022).

Raw sequence reads have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive under BioProject accession no. PRJNA765214 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=PRJNA765214, NCBI, 2022).

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-8-163-2022-supplement.

Group I: Fabian Bauer, Lorenz Baumgartner, Lisa Brandl, Michael Buchmayer, Karl Daschl, Rene Dietrich, Stefan Ebner, Margarete Jäger, Michaela Kiss, Lea Kneissl, Katja Langmann, Elias Mauerhofer, Jakob Paschinger, Tobias Rabl, Sophie Schachenhuber, Josef Schmid, Marlene Steinbatz. Group II: Mathias Ettenauer, Lorenz Hauck, Mathias Herl, Johannes Honsig, Thomas Gangl, Anja Glaser, Gabriel Hümer, Georg Lenzatti, Stefan Lichtscheidl, Lena Mayer, Valentin Oppenauer, Jacob Rennhofer, Katharina Schönner, Ciara Seywald. Group III: Jan Gamzunov, Anna Hess, Christoph Schurm, Klaus Stacher, Lena Ungersböck, Florian Valachovich, Mirjam Weissmann, Marius Wittek, Jennifer Wosak, Valentin Zahel, Lucas Züger.

TS, RA, and AD designed the study. TS, HB, SG, and EK performed sampling with support from students of biology projects groups I, II, and III. EK developed lab protocols, and EP optimised the lab protocols and performed the DNA extraction and PCR amplification. TS, RA, and AD analysed the data. The manuscript was written by AD, TS, and RA with contributions from all co-authors.

The contact author has declared that neither they nor their co-authors have any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We thank Michael Schwarz for preparing the map in Fig. 1.

This work was supported by the Austrian Ministry of Education, Science and Research (BMBWF) through a Sparkling Science Grant to Taru Sandén, Helene Berthold, Elena Kinz, Anne Daebeler, Roey Angel, and Susanne Grausenburger (SPA 06/044 TeaTime4Schools). In addition, Eva Petrová and Roey Angel were supported by the Czech MEYS (EF16_013/0001782 – SoWa Ecosystems Research). Anne Daebeler was supported by the FWF grant T938.

This paper was edited by Ingrid Lubbers and reviewed by Thomas Reitz and one anonymous referee.

Albright, M. B. N. and Martiny, J. B. H.: Dispersal alters bacterial diversity and composition in a natural community, ISME J., 12, 296–299, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2017.161, 2018.

Albright, M. B. N., Chase, A. B., and Martiny, J. B. H.: Experimental Evidence that Stochasticity Contributes to Bacterial Composition and Functioning in a Decomposer Community, mBio, 10, e00568-19, https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00568-19, 2019.

Aleklett, K., Ohlsson, P., Bengtsson, M., and Hammer, E. C.: Fungal foraging behaviour and hyphal space exploration in micro-structured Soil Chips, ISME J., 15, 1782–1793, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-020-00886-7, 2021.

Allison, S. D., Wallenstein, M. D., and Bradford, M. A.: Soil-carbon response to warming dependent on microbial physiology, Nat. Geosci., 3, 336–340, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo846, 2010.

Allison, S. D., Lu, Y., Weihe, C., Goulden, M. L., Martiny, A. C., Treseder, K. K., and Martiny, J. B. H.: Microbial abundance and composition influence litter decomposition response to environmental change, Ecology, 94, 714–725, https://doi.org/10.1890/12-1243.1, 2013.

Aneja, M. K., Sharma, S., Fleischmann, F., Stich, S., Heller, W., Bahnweg, G., Munch, J. C., and Schloter, M.: Microbial Colonization of Beech and Spruce LitterInfluence of Decomposition Site and Plant Litter Species on the Diversity of Microbial Community, Microb. Ecol., 52, 127–135, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-006-9006-3, 2006.

Angel, R.: General Bacteria and Archaea 16S-rRNA (515Fmod-806Rmod) for Illumina Amplicon Sequencing V.4, protocols.io [data set], https://doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.bsxanfie, 2021.

Angel, R.: roey-angel/TeaTime4Schools: First release – EGU SOIL (V1.0), Zenodo [code], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6340082, 2022.

Bailey, V. L., Fansler, S. J., Stegen, J. C., and McCue, L. A.: Linking microbial community structure to β-glucosidic function in soil aggregates, ISME J, 7, 2044–2053, 2013.

Benjamini, Y. and Hochberg, Y.: Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing, J. Roy. Stat. Soc. B, 57, 289–300, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x, 1995.

Boddy, L.: Interspecific combative interactions between wood-decaying basidiomycetes, FEMS Microbiol. Ecol., 31, 185–194, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6941.2000.tb00683.x, 2000.

Bray, S. R., Kitajima, K., and Mack, M. C.: Temporal dynamics of microbial communities on decomposing leaf litter of 10 plant species in relation to decomposition rate, Soil Biol. Biochem., 49, 30–37, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.02.009, 2012.

Buchholz, J., Querner, P., Paredes, D., Bauer, T., Strauss, P., Guernion, M., Scimia, J., Cluzeau, D., Burel, F., Kratschmer, S., Winter, S., Potthoff, M., and Zaller, J. G.: Soil biota in vineyards are more influenced by plants and soil quality than by tillage intensity or the surrounding landscape, Sci. Rep.-UK, 7, 17445, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17601-w, 2017.

Callahan, B. J., McMurdie, P. J., Rosen, M. J., Han, A. W., Johnson, A. J. A., and Holmes, S. P.: DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data, Nat. Meth., 13, 581–583, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3869, 2016.

Chen, T., Nomura, K., Wang, X., Sohrabi, R., Xu, J., Yao, L., Paasch, B. C., Ma, L., Kremer, J., Cheng, Y., Zhang, L., Wang, N., Wang, E., Xin, X.-F., and He, S. Y.: A plant genetic network for preventing dysbiosis in the phyllosphere, Nature, 580, 653–657, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2185-0, 2020.

Cotrufo, M. F., Wallenstein, M. D., Boot, C. M., Denef, K., and Paul, E.: The Microbial Efficiency-Matrix Stabilization (MEMS) framework integrates plant litter decomposition with soil organic matter stabilization: do labile plant inputs form stable soil organic matter?, Glob. Change Biol., 19, 988–995, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12113, 2013.

Daebeler, A., Bodelier, P. L. E., Yan, Z., Hefting, M. M., Jia, Z., and Laanbroek, H. J.: Interactions between Thaumarchaea Nitrospira and methanotrophs modulate autotrophic nitrification in volcanic grassland soil, ISME J., 8, 2397–2410, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2014.81, 2014.

Davis, N. M., Proctor, D. M., Holmes, S. P., Relman, D. A., and Callahan, B. J.: Simple statistical identification and removal of contaminant sequences in marker-gene and metagenomics data, Microbiome, 6, 226, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-018-0605-2, 2018.

de Boer, W. and van der Wal, A.: Chapter 8 Interactions between saprotrophic basidiomycetes and bacteria, in: British Mycological Society Symposia Series, Vol. 28, edited by: Boddy, L., Frankland, J. C., and van West, P., Academic Press, 143–153, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0275-0287(08)80010-0, 2008.

de Boer, W., Folman, L. B., Summerbell, R. C., and Boddy, L.: Living in a fungal world: impact of fungi on soil bacterial niche development, FEMS Microbiol. Rev., 29, 795–811, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.femsre.2004.11.005, 2005.

du Plessis, L., Rose, S. H., and van Zyl, W. H.: Exploring improved endoglucanase expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains, Appl. Microbiol. Biot., 86, 1503–1511, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-009-2403-z, 2009.

Elumeeva, T. G., Onipchenko, V. G., Akhmetzhanova, A. A., Makarov, M. I., and Keuskamp, J. A.: Stabilization versus decomposition in alpine ecosystems of the Northwestern Caucasus: The results of a tea bag burial experiment, J. Mt. Sci., 15, 1633–1641, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-018-4960-z, 2018.

Falkowski, P. G., Fenchel, T., and Delong, E. F.: The Microbial Engines That Drive Earths Biogeochemical Cycles, Science, 320, 1034–1039, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1153213, 2008.

Faust, K. and Raes, J.: Microbial interactions: from networks to models, Nat. Rev. Microbiol., 10, 538–550, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2832, 2012.

Fernandes, A. D., Macklaim, J. M., Linn, T. G., Reid, G., and Gloor, G. B.: ANOVA-like differential expression (ALDEx) analysis for mixed population RNA-Seq, PLoS One, 8, e67019, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0067019, 2013.

Freschet, G. T., Weedon, J. T., Aerts, R., van Hal, J. R., and Cornelissen, J. H. C.: Interspecific differences in wood decay rates: insights from a new short-term method to study long-term wood decomposition, J. Ecol., 100, 161–170, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2011.01896.x, 2011.

Garbeva, P., Hordijk, C., Gerards, S., and de Boer, W.: Volatile-mediated interactions between phylogenetically different soil bacteria, Front. Microbiol., 5, 289, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00289, 2014.

Gardes, M. and Bruns, T. D.: ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes–application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts, Mol. Ecol., 2, 113–118, 1993.

Glassman, S. I., Weihe, C., Li, J., Albright, M. B. N., Looby, C. I., Martiny, A. C., Treseder, K. K., Allison, S. D., and Martiny, J. B. H.: Decomposition responses to climate depend on microbial community composition, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 115, 11994–11999, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1811269115, 2018.

Graham, E. B., Knelman, J. E., Schindlbacher, A., Siciliano, S., Breulmann, M., Yannarell, A., Beman, J. M., Abell, G., Philippot, L., Prosser, J., Foulquier, A., Yuste, J. C., Glanville, H. C., Jones, D. L., Angel, R., Salminen, J., Newton, R. J., Bürgmann, H., Ingram, L. J., Hamer, U., Siljanen, H. M. P., Peltoniemi, K., Potthast, K., Bañeras, L., Hartmann, M., Banerjee, S., Yu, R.-Q., Nogaro, G., Richter, A., Koranda, M., Castle, S. C., Goberna, M., Song, B., Chatterjee, A., Nunes, O. C., Lopes, A. R., Cao, Y., Kaisermann, A., Hallin, S., Strickland, M. S., Garcia-Pausas, J., Barba, J., Kang, H., Isobe, K., Papaspyrou, S., Pastorelli, R., Lagomarsino, A., Lindström, E. S., Basiliko, N., and Nemergut, D. R.: Microbes as Engines of Ecosystem Function: When Does Community Structure Enhance Predictions of Ecosystem Processes?, Front. Microbiol., 7, 214, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00214, 2016.

Guo, T., Zhang, Q., Ai, C., Liang, G., He, P., Lei, Q., and Zhou, W.: Analysis of microbial utilization of rice straw in paddy soil using a DNA-SIP approach, Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J., 84, 99–114, https://doi.org/10.1002/saj2.20019, 2020.

Ho, A., Angel, R., Veraart, A. J., Daebeler, A., Jia, Z., Kim, S. Y., Kerckhof, F.-M., Boon, N., and Bodelier, P. L. E.: Biotic Interactions in Microbial Communities as Modulators of Biogeochemical Processes: Methanotrophy as a Model System, Front. Microbiol., 7, 1285, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.01285, 2016.

Hoppe, B., Purahong, W., Wubet, T., Kahl, T., Bauhus, J., Arnstadt, T., Hofrichter, M., Buscot, F., and Krüger, D.: Linking molecular deadwood-inhabiting fungal diversity and community dynamics to ecosystem functions and processes in Central European forests, Fungal Divers., 77, 367–379, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13225-015-0341-x, 2015.

Horn, H. S.: Measurement of Overlap in Comparative Ecological Studies, Am. Nat., 100, 419–424, https://doi.org/10.1086/282436, 1966.

Jackson, C. A., Couger, M. B., Prabhakaran, M., Ramachandriya, K. D., Canaan, P., and Fathepure, B. Z.: Isolation and characterization ofRhizobiumsp. strain YS-1r that degrades lignin in plant biomass, J. Appl. Microbiol., 122, 940–952, https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.13401, 2017.

Jiménez, D. J., Korenblum, E., and van Elsas, J. D.: Novel multispecies microbial consortia involved in lignocellulose and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural bioconversion, Appl. Microbiol. Biot., 98, 2789–2803, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-013-5253-7, 2013.

Jiménez, D. J., Dini-Andreote, F., and van Elsas, J.: Metataxonomic profiling and prediction of functional behaviour of wheat straw degrading microbial consortia, Biotechnol. Biofuels, 7, 92, https://doi.org/10.1186/1754-6834-7-92, 2014.

Kandeler, E.: Bestimmung der N-Mineralisation im anaeroben Brutversuch, in: Bodenbiologische Arbeitsmethoden, 2nd Edn., 160–161, edited by: Schinner, F., Öhlinger, R., Kandeler, E., and Margesin, R., Springer Verlag, Berling, Heidelberg, Germany, 1993.

Keeney, D. R.: Nitrogen availability indices, in: Methods of Soil Analysis. Part II, 2nd Edn., edited by: Page, A. L., Millet, R. H., and Keeney, D. R., Agronomy Monograph No. 9, 711–730, American Society of Agronomy, Madison, USA, 1982.

Keuskamp, J. A., Dingemans, B. J. J., Lehtinen, T., Sarneel, J. M., and Hefting, M. M.: Tea Bag Index: a novel approach to collect uniform decomposition data across ecosystems, Meth. Ecol. Evol., 4, 1070–1075, https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210x.12097, 2013.

Kirschbaum, M. U. F.: The temperature dependence of soil organic matter decomposition and the effect of global warming on soil organic C storage, Soil Biol. Biochem., 27, 753–760, https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-0717(94)00242-s, 1995.

Knorr, K., Jørgensen, L. N., and Nicolaisen, M.: Fungicides have complex effects on the wheat phyllosphere mycobiome, PLOS ONE, 14, e0213176, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213176, 2019.

Koga, S., Ogawa, J., Choi, Y.-M., and Shimizu, S.: Novel bacterial peroxidase without catalase activity from Flavobacterium meningosepticum: purification and characterization, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1435, 117–126, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00190-9, 1999.

Lennon, J. T. and Jones, S. E.: Microbial seed banks: the ecological and evolutionary implications of dormancy, Nat. Rev. Microbiol., 9, 119–130, 2011.

Lenth, R. V.: emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans (last access: 9 March 2022), 2021.

Liang, C., Schimel, J. P., and Jastrow, J. D.: The importance of anabolism in microbial control over soil carbon storage, Nat. Microbiol., 2, 17105, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.105, 2017.

López, M. J., Nichols, N. N., Dien, B. S., Moreno, J., and Bothast, R. J.: Isolation of microorganisms for biological detoxification of lignocellulosic hydrolysates, Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 64, 125–131, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-003-1401-9, 2004.

Lynd, L. R., Weimer, P. J., van, Z. W. H., and Pretorius, I. S.: Microbial cellulose utilization: fundamentals and biotechnology, Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev., 66, 506–577, 2002.

Maron, P.-A., Sarr, A., Kaisermann, A., Lévêque, J., Mathieu, O., Guigue, J., Karimi, B., Bernard, L., Dequiedt, S., Terrat, S., Chabbi, A., and Ranjard, L.: High microbial diversity promotes soil ecosystem functioning, Appl. Environ. Microb., 84, e02738-17, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02738-17, 2018.

Martin, M.: Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads, EMBnet.journal, 17, 10–12, https://doi.org/10.14806/ej.17.1.200, 2011.

Martinez, D., Berka, R. M., Henrissat, B., Saloheimo, M., Arvas, M., Baker, S. E., Chapman, J., Chertkov, O., Coutinho, P. M., Cullen, D., Danchin, E. G. J., Grigoriev, I. V., Harris, P., Jackson, M., Kubicek, C. P., Han, C. S., Ho, I., Larrondo, L. F., de Leon, A. L., Magnuson, J. K., Merino, S., Misra, M., Nelson, B., Putnam, N., Robbertse, B., Salamov, A. A., Schmoll, M., Terry, A., Thayer, N., Westerholm-Parvinen, A., Schoch, C. L., Yao, J., Barabote, R., Barbote, R., Nelson, M. A., Detter, C., Bruce, D., Kuske, C. R., Xie, G., Richardson, P., Rokhsar, D. S., Lucas, S. M., Rubin, E. M., Dunn-Coleman, N., Ward, M., and Brettin, T. S.: Genome sequencing and analysis of the biomass-degrading fungus Trichoderma reesei (syn. Hypocrea jecorina), Nat. Biotechnol., 26, 553–560, https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt1403, 2008.

Mathieu, Y., Gelhaye, E., Dumarçay, S., Gérardin, P., Harvengt, L., and Buée, M.: Selection and validation of enzymatic activities as functional markers in wood biotechnology and fungal ecology, J. Microbiol. Meth., 92, 157–163, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mimet.2012.11.017, 2013.

Matsuyama, H., Katoh, H., Ohkushi, T., Satoh, A., Kawahara, K., and Yumoto, I.: Sphingobacterium kitahiroshimense sp. nov. isolated from soil, Int. J. Syst. Evol. Micr., 58, 1576–1579, https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.65791-0, 2008.

McBride, M. J., Xie, G., Martens, E. C., Lapidus, A., Henrissat, B., Rhodes, R. G., Goltsman, E., Wang, W., Xu, J., Hunnicutt, D. W., Staroscik, A. M., Hoover, T. R., Cheng, Y.-Q., and Stein, J. L.: Novel Features of the Polysaccharide-Digesting Gliding Bacterium Flavobacterium johnsoniae as Revealed by Genome Sequence Analysis, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 75, 6864–6875, https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.01495-09, 2009.

McGuire, K. L. and Treseder, K. K.: Microbial communities and their relevance for ecosystem models: Decomposition as a case study, Soil Biol. Biochem., 42, 529–535, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.11.016, 2010.

McMurdie, P. J. and Holmes, S.: phyloseq: An R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data, PLoS ONE, 8, e61217, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0061217, 2013.

Mcardle, B. and Anderson, M.: Fitting Multivariate Models to Community Data: A Comment on Distance-Based Redundancy Analysis, Ecology, 82, 290–297, https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2001)082[0290:fmmtcd]2.0.co;2, 2001.

Naqib, A., Poggi, S., and Green, S. J.: Deconstructing the polymerase chain reaction II: an improved workflow and effects on artifact formation and primer degeneracy, PeerJ, 7, e7121, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.7121, 2019.

NCBI: Teabag microbiome – Klosterneuburg Targeted loci environmental, NCBI [data set, sample], https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=PRJNA765214, last access: 9 March 2022.

Newsham, K. K., Garnett, M. H., Robinson, C. H., and Cox, F.: Discrete taxa of saprotrophic fungi respire different ages of carbon from Antarctic soils, Sci. Rep.-UK, 8, 7866, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25877-9, 2018.

Nilsson, R. H., Larsson, K.-H., Taylor, A. F. S., Bengtsson-Palme, J., Jeppesen, T. S., Schigel, D., Kennedy, P., Picard, K., Glöckner, F. O., Tedersoo, L., Saar, I., Kõljalg, U., and Abarenkov, K.: The UNITE database for molecular identification of fungi: handling dark taxa and parallel taxonomic classifications, Nucleic Acids Research, 47, D259–D264, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky1022, 2018.

Oksanen, J., Blanchet, F. G., Friendly, M., Kindt, R., Legendre, P., McGlinn, D., Minchin, P. R., O'Hara, R. B., Simpson, G. L., Solymos, P., Stevens, M. H. H., Szoecs, E., and Wagner, H.: Vegan: Community Ecology Package, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (last access: 9 March 2022), 2018.

Parks, D. H., Tyson, G. W., Hugenholtz, P., and Beiko, R. G.: STAMP: statistical analysis of taxonomic and functional profiles, Bioinformatics, 30, 3123–3124, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu494, 2014.

Pioli, S., Sarneel, J., Thomas, H. J. D., Domene, X., Andrés, P., Hefting, M., Reitz, T., Laudon, H., Sandén, T., Piscová, V., Aurela, M., and Brusetti, L.: Linking plant litter microbial diversity to microhabitat conditions environmental gradients and litter mass loss: Insights from a European study using standard litter bags, Soil Biol. Biochem., 144, 107778, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2020.107778, 2020.

Prescott, C. E.: Litter decomposition: what controls it and how can we alter it to sequester more carbon in forest soils?, Biogeochemistry, 101, 133–149, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-010-9439-0, 2010.

Purahong, W., Wubet, T., Lentendu, G., Schloter, M., Pecyna, M. J., Kapturska, D., Hofrichter, M., Krüger, D., and Buscot, F.: Life in leaf litter: novel insights into community dynamics of bacteria and fungi during litter decomposition, Mol. Ecol., 25, 4059–4074, https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.13739, 2016.

Quast, C., Pruesse, E., Yilmaz, P., Gerken, J., Schweer, T., Yarza, P., Peplies, J., and Glöckner, F. O.: The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools, Nucleic Acids Res., 41, D590–D596, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks1219, 2012.

R Core Team: R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, http://www.R-project.org/ (last access: 28 June 2021), 2020.

Sandén, T., Spiegel, H., Wenng, H., Schwarz, M., and Sarneel, J. M.: Learning Science during Teatime: Using a Citizen Science Approach to Collect Data on Litter Decomposition in Sweden and Austria, Sustainability, 12, 7745, https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187745, 2020.

Sandén, T., Wawra, A., Berthold, H., Miloczki, J., Schweinzer, A., Gschmeidler, B., Spiegel, H., Debeljak, M., and Trajanov, A.: TeaTime4Schools: Using Data Mining Techniques to Model Litter Decomposition in Austrian Urban School Soils, Front. Ecol. Evol., 9, 703794, https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2021.703794, 2021.

Sarneel, J. M., Sundqvist, M. K., Molau, U., Björkman, M. P., and Alatalo, J. M.: Decomposition rate and stabilization across six tundra vegetation types exposed to >20 years of warming, Sci. Total Environ., 724, 138304, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138304, 2020.

Schmidt, M. W. I., Torn, M. S., Abiven, S., Dittmar, T., Guggenberger, G., Janssens, I. A., Kleber, M., Kogel-Knabner, I., Lehmann, J., Manning, D. A. C., Nannipieri, P., Rasse, D. P., Weiner, S., and Trumbore, S. E.: Persistence of soil organic matter as an ecosystem property, Nature, 478, 49–56, 2011.

Talbot, J. M. and Treseder, K. K.: Dishing the dirt on carbon cycling, Nat. Clim. Change, 1, 144–146, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1125, 2011.

Talbot, J. M. and Treseder, K. K.: Interactions among lignin cellulose, and nitrogen drive litter chemistrydecay relationships, Ecology, 93, 345–354, https://doi.org/10.1890/11-0843.1, 2012.

Talia, P., Sede, S. M., Campos, E., Rorig, M., Principi, D., Tosto, D., Hopp, H. E., Grasso, D., and Cataldi, A.: Biodiversity characterization of cellulolytic bacteria present on native Chaco soil by comparison of ribosomal RNA genes, Res. Microbiol., 163, 221–232, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resmic.2011.12.001, 2012.

MGnify: Who eats the tough stuff DNA stable isotope probing (SIP) of bacteria and fungi degrading 13C-labelled lignin and cellulose in forest soils, Sampling event dataset, GBIF.org [data set], https://doi.org/10.15468/cewp3n, 2020.

Tatzber, M., Schlatter, N., Baumgarten, A., Dersch, G., Körner, R., Lehtinen, T., … Spiegel, H.: KMnO4 determination of active carbon for laboratory routines: three long-term field experiments in Austria, Soil Res., 53, 190–204, https://doi.org/10.1071/SR14200, 2015.

Thompson, L. R., Sanders, J. G., McDonald, D., Amir, A., Ladau, J., Locey, K. J., Prill, R. J., Tripathi, A., Gibbons, S. M., Ackermann, G., Navas-Molina, J. A., Janssen, S., Kopylova, E., Vázquez-Baeza, Y., González, A., Morton, J. T., Mirarab, S., Zech, X. Z., Jiang, L., Haroon, M. F., Kanbar, J., Zhu, Q., Jin, S. S., Kosciolek, T., Bokulich, N. A., Lefler, J., Brislawn, C. J., Humphrey, G., Owens, S. M., Hampton-Marcell, J., Berg-Lyons, D., McKenzie, V., Fierer, N., Fuhrman, J. A., Clauset, A., Stevens, R. L., Shade, A., Pollard, K. S., Goodwin, K. D., Jansson, J. K., Gilbert, J. A., and Knight, R.: A communal catalogue reveals Earth's multiscale microbial diversity, Nature, 551, 457–463, 2017.

Walters, W., Hyde, E. R., Berg-Lyons, D., Ackermann, G., Humphrey, G., Parada, A., Gilbert, J. A., Jansson, J. K., Caporaso, J. G., Fuhrman, J. A., Apprill, A., and Knight, R.: Improved bacterial 16S rRNA gene (v4 and v4-5) and fungal internal transcribed spacer marker gene primers for microbial community surveys, mSystems, 1, e00009-15, https://doi.org/10.1128/mSystems.00009-15, 2016.

Wang, Y., Liu, Q., Yan, L., Gao, Y., Wang, Y., and Wang, W.: A novel lignin degradation bacterial consortium for efficient pulping, Bioresource Technol., 139, 113–119, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2013.04.033, 2013.

Wei, H., Ma, R., Zhang, J., Saleem, M., Liu, Z., Shan, X., Yang, J., and Xiang, H.: Crop-litter type determines the structure and function of litter-decomposing microbial communities under acid rain conditions, Sci. Total Environ., 713, 136600, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136600, 2020.

Wickham, H.: ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis, Springer-Verlag, New York, USA, ISBN 978-3-319-24277-4, 2016.

Wieder, W. R., Grandy, A. S., Kallenbach, C. M., and Bonan, G. B.: Integrating microbial physiology and physio-chemical principles in soils with the MIcrobial-MIneral Carbon Stabilization (MIMICS) model, Biogeosciences, 11, 3899–3917, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-11-3899-2014, 2014.

Wilhelm, R. C., Singh, R., Eltis, L. D., and Mohn, W. W.: Bacterial contributions to delignification and lignocellulose degradation in forest soils with metagenomic and quantitative stable isotope probing, ISME J., 13, 413–429, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-018-0279-6, 2019.

Wilpiszeski, R. L., Aufrecht, J. A., Retterer, S. T., Sullivan, M. B., Graham, D. E., Pierce, E. M., Zablocki, O. D., Palumbo, A. V., and Elias, D. A.: Soil aggregate microbial communities: towards understanding microbiome interactions at biologically relevant scales, Appl. Environ. Microb., 85, e00324-19, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00324-19, 2019.

Anjos, L., Gaistardo, C., Deckers, J., Dondeyne, S., Eberhardt, E., Gerasimova, M., Harms, B., Jones, A., Krasilnikov, P., Reinsch, T., Vargas, R., and Zhang, G.: World reference base for soil resources 2014 International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps, 3rd ed., edited by: Schad, P., Van Huyssteen, C., and Micheli, E., FAO, Rome (Italy), ISBN 978-92-5-108369-7, 2015.

Yan, J., Wang, L., Hu, Y., Tsang, Y. F., Zhang, Y., Wu, J., Fu, X., and Sun, Y.: Plant litter composition selects different soil microbial structures and in turn drives different litter decomposition pattern and soil carbon sequestration capability, Geoderma, 319, 194–203, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2018.01.009, 2018.

Yuste, J. C., Peñuelas, J., Estiarte, M., Garcia-Mas, J., Mattana, S., Ogaya, R., Pujol, M., and Sardans, J.: Drought-resistant fungi control soil organic matter decomposition and its response to temperature, Glob. Change Biol., 17, 1475–1486, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02300.x, 2010.

Zheng, H., Yang, T., Bao, Y., He, P., Yang, K., Mei, X., Wei, Z., Xu, Y., Shen, Q., and Banerjee, S.: Network analysis and subsequent culturing reveal keystone taxa involved in microbial litter decomposition dynamics, Soil Biol. Biochem., 157, 108230, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2021.108230, 2021.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Materials and methods

- Molecular analyses of prokaryotic and fungal community structures

- Results and discussion

- Conclusions

- Code availability

- Data availability

- Team list

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Supplement

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Materials and methods

- Molecular analyses of prokaryotic and fungal community structures

- Results and discussion

- Conclusions

- Code availability

- Data availability

- Team list

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Supplement