the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Soil erosion in Mediterranean olive groves: a review

Emilio Jesús González-Sánchez

Filippo Milazzo

Olive groves are a defining feature of the Mediterranean landscape, economy, and culture. However, this keystone agroecosystem is under severe threat from soil erosion, a problem exacerbated by the region's unique topographic, climatic conditions and agricultural practices. Although soil erosion in olive groves has been extensively studied, significant uncertainties remain due to the high variability of scales and measurement methods. Knowledge gaps persist regarding the average soil loss rates and runoff coefficients as well as the effects of different management approaches and the influence of triggering factors on soil erosion rates. So far, an effort to quantify this effect on Mediterranean olive cultivation has not been made comprehensively. Therefore, the aim of this literature review is to discern clearer patterns and trends that are often obscured by the overall heterogeneity of the available data. By systematically analysing the data according to measurement methodology, this review provides clear answers to these knowledge gaps and reveals a consistent narrative about the primary drivers of soil loss. While natural factors like topography, rainfall intensity and soil properties establish a baseline risk, this review shows that agricultural management, particularly the presence of groundcovers, is the pivotal factor controlling soil degradation. The long-standing debate on erosion severity is largely reconciled by the finding that reported rates are highly dependent on the measurement methodology, and hence on the spatial and temporal scale. Conservation practices consistently reduce soil loss by more than half, an effect far more pronounced for sediment control than for runoff reduction. Ultimately, the path to sustainability requires a shift away from conventional tillage and bare-soil management towards the widespread adoption of vegetation/groundcover, driven by effective policies and a commitment to multi-scale and multi-proxy research to improve predictive models.

- Article

(1825 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Soil erosion is widely recognized as one of the most significant forms of soil degradation worldwide. The Mediterranean region is particularly vulnerable due to a confluence of natural and anthropogenic factors. Natural drivers such as sparse vegetation cover, low soil structural stability, steep slopes, and intense rainstorms are compounded by human activities including land cover change, forest fires, intensive grazing, and soil tillage practices, all of which exacerbate erosion risks.

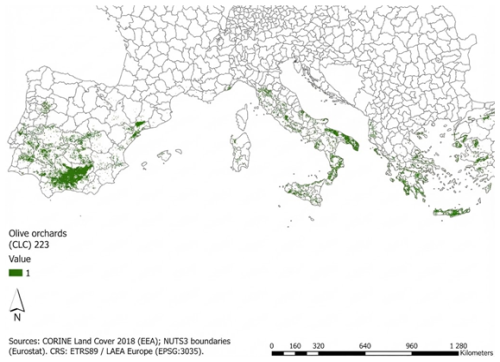

Among Mediterranean agricultural systems, olive groves (Olea europaea) stand out both economically and culturally, with more than 95 % of global olive production concentrated in the Mediterranean basin. This importance is visually represented in Fig. 1, which maps the distribution of olive orchards across the European Mediterranean, highlighting the crop's dominance in southern Spain, Italy, and Greece. However, these groves are frequently situated on marginal, low-fertility, and steeply sloping land, where soil erosion constitutes a major threat to their long-term sustainability (Gómez et al., 2009a; Vanwalleghem et al., 2010). It is essential to recognize that the primary driver of this degradation is not the olive tree itself or the local conditions, but the conventional soil management practices associated with its cultivation. Both traditional and modern olive farming has been characterized by the systematic removal of competing vegetation through frequent mechanical tillage (Fig. 2), which degrades soil structure and leaves the ground surface bare and vulnerable (Álvarez et al., 2007; Gómez et al., 2004). For instance, in Spain, despite the promotion of conservation agriculture, over 50 % of the olive growing area still lacks vegetation cover, with the majority of protected land relying on spontaneous rather than cover crops (MAPA, 2024). A similar pattern is observed in Italy, where tillage remains the predominant practice in conventional orchards (ISMEA, 2025), with permanent vegetation cover largely restricted to the ∼ 25 % of the olive-growing area managed under organic farming protocols or specific agri-environmental schemes. This practice of maintaining bare soil is deeply rooted in a cultural identity where a “clean” tilled, weed-free field is perceived as signs of diligent farming, while the presence of groundcover is seen as neglect (Rodrigo-Comino et al., 2020; Sastre et al., 2017). When this practice is combined with the common siting of olive groves on steep, erodible slopes, the conditions for severe soil erosion are perfected.

Figure 1Distribution of olive orchards in the European Mediterranean basin. Data source: CORINE Land Cover 2018 (EEA) and NUTS3 boundaries (Eurostat).

Figure 2Image of an olive orchard under conventional tillage bare-soil management (systematic removal of competing vegetation through frequent mechanical tillage) on steep slopes in Montefrío (Granada). (Photo by Andrés Peñuela.)

Accurate, evidence-based knowledge of erosion rates is essential for defining effective soil conservation policies. However, the scientific literature on soil erosion in olive groves is marked by significant debate and seemingly contradictory findings. A frequently cited soil loss estimate of 80 t ha−1 yr−1 for south Spain groves is based on USLE model estimates (López-Cuervo, 1990). This very high soil loss rate is supported by long-term estimates based on soil truncation methods, in particular, on tree mound measurements in Jordan, 132 t ha−1 yr−1 (Kraushaar et al., 2014), and in South Spain, 184 t ha−1 yr−1 (Vanwalleghem et al., 2010) and on fallout radionuclides in Spain, 75 t ha−1 yr−1 (García-Gamero et al., 2024a) and runoff plot studies in Greece, 56 t ha−1 yr−1 (Koulouri and Giourga, 2007) and in Spain 60 t ha−1 yr−1 (Gómez et al., 2017). These figures paint an alarming picture of an agroecosystem in crisis. In contrast, (Fleskens and Stroosnijder, 2007) argue that average rates rarely exceed 10 t ha−1 yr−1. In response, Gómez et al. (2008) criticized Fleskens and Stroosnijder's (2007) incomplete interpretation and conclusions drawn from short-term plot-scale experiments. In any case, erosion rates far exceed natural soil formation rates, depleting this vital resource (Huber et al., 2008)

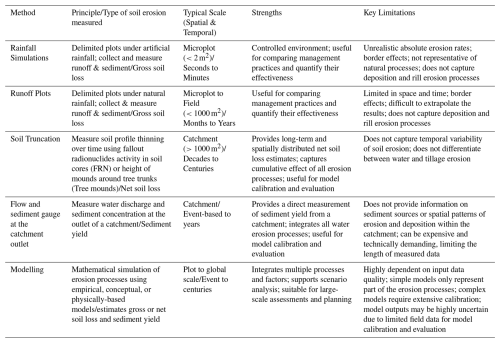

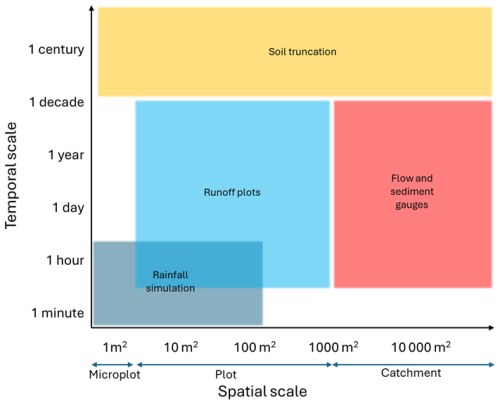

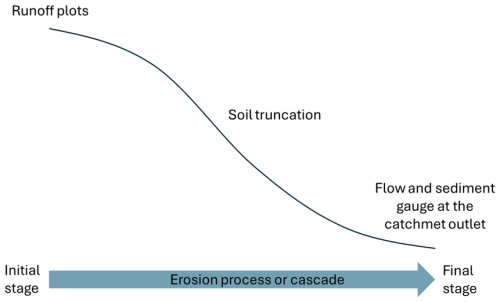

Understanding soil erosion in olive groves is complicated by the wide array of methods used for its quantification, each with inherent strengths, limitations, and, most critically, different spatial and temporal scales of operation. It must be noted that most, if not all, of these methods are standard approaches widely applied for soil erosion assessment, not only in olive groves but also across a broad range of agricultural systems. These methods can be broadly classified into field measurements and predictive models (Table 1). Field measurements provide direct empirical data but vary significantly in what they measure. A crucial distinction must be made between methods that estimate gross soil loss, i.e. the total amount of soil detached and transported from a specific area, and those that estimate net soil loss, which accounts for both erosion and deposition within a larger landscape unit. Additionally, some methods focus on sediment yield, which quantifies the amount of eroded soil that actually exits the catchment or watershed, typically measured at the outlet. Field measurements can be divided into runoff simulations (Palese et al., 2015; Repullo-Ruibérriz De Torres et al., 2018), runoff plots (Espejo-Pérez et al., 2013), soil truncation studies based on fallout radionuclides (FRN) (Gdiri et al., 2024; Mabit et al., 2012) and tree mound measurements (Kraushaar et al., 2014; Vanwalleghem et al., 2010), and sediment yield measurements at the catchment outlet (Gómez et al., 2014; Taguas et al., 2013). Small spatial scale studies, such as rainfall simulation and runoff plots, tend to miss key catchment erosion processes such as rill and gully formation, tillage erosion, and sedimentation within fields. Nevertheless, runoff plots are uniquely capable of capturing temporal variability at a high resolution, enabling the detailed analysis of erosive responses to individual storm events. A significant constraint, however, is their typically brief experimental duration – often under a decade – however, due to their typically limited experimental duration (often less than 10 years), these methods generally fail to capture the cumulative impacts of long-term land management changes. Long-term historical methods, such as tree mound measurements and fallout radionuclide-based estimates, can capture catchment erosion processes and cumulative effects, such as the long-term effects of land use change or soil conservation practices, but are inadequate for capturing the temporal variability and episodic high-intensity events typical of Mediterranean climates. No single method provides a complete picture; rather, each offers unique insights depending on the scale and timeframe of analysis (Fig. 3).

Figure 3Spatial and temporal scales of application for different land measurements methods applied in the literature to estimate soil loss rates and runoff coefficients in olive groves.

Models allow for long-term, large-scale predictions with resolutions that exceed the limitations of field experiments. However, their reliability is strongly tied to input data quality. Improper calibration and evaluation, or application beyond a model's original scope, often lead to misleading results, highlighting the “garbage in, garbage out” principle. Some examples of models applied to simulate soil erosion in olive groves are AnnAGNPS (Bingner and Theurer, 2001), WaTEM/SEDEM (Van Oost et al., 2000), SEDD (Ferro and Minacapilli, 1995) and the Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE) (Renard, 1997). RUSLE is the most widely used model, however it was designed to be applied at the plot scale and hence, it only estimates gross soil loss. When its application is upscaled to larger areas without accounting for deposition, the accuracy of its predictions can be significantly compromised (Boix-Fayos et al., 2006; De Vente and Poesen, 2005). Model validation/evaluation is particularly challenging due to scale mismatches and the scarcity of long-term, high-quality data. Moreover, the inconsistency in field measurement results significantly limits the evaluation of models, making it difficult to ascertain if a model behaves as expected or if its outputs align with real-world observations under comparable conditions. Therefore, investing in long-term monitoring and consistent data is not just an academic pursuit but a prerequisite for developing reliable, policy-relevant modelling tools.

This review analyses existing studies on soil erosion in Mediterranean olive groves, grouping them by measurement methodology, and hence in similar spatial and temporal scales. The aim is to discern clearer patterns and trends that are often obscured by the overall heterogeneity of the available data, thereby addressing a significant challenge in the current scientific literature. This will provide general findings to evaluate model performance and assess the effectiveness of current management practices, ultimately contributing to more robust conservation strategies. This systematic approach will also address key research questions, including: What are the typical soil loss rates and runoff ratios in Mediterranean olive groves? What is the influence of factors such as topography, soil, vegetation, and climate on soil loss and runoff generation? What is the impact of soil conservation practices?

2.1 Data collection and analysis

A dataset of erosion rates and soil loss measurements was constructed from published literature focusing on Mediterranean olive groves, i.e. regions with a Mediterranean climate (Köppen Csa/Csb), primarily focusing on the Mediterranean basin where >95 % of olive production occurs. The bibliometric analysis used a systematic screening approach (Milazzo et al., 2023) to identify international studies on soil erosion in olive-growing systems published between 1985 and 2025, searching Scopus and CAB Abstracts for reproducibility and broad coverage. The search strings were built through an iterative process of testing, evaluation, and refinement. Initially, a search component was constructed for the concept “soil erosion”, incorporating relevant synonyms and terms associated with soil degradation. A second search component targeted olive orchards and their descriptive variants (“olive orchard”, “olive grove”, “olive plantation”, “olive farm”, Olea europaea). A third component covered the full range of erosion processes relevant to olive-growing landscapes, including water erosion, sheet and rill erosion, gully formation, wind erosion, tillage-induced erosion, sediment transport, soil loss, and broader land degradation dynamics. Finally, a fourth stage excluded studies that did not meet these requirements: (i) report quantitative erosion rate estimates; (ii) focus on hillslope erosion or both hillslope and gully erosion processes in olive orchards; and (iii) involve either direct field measurements or modelling approaches that applied a calibration or validation procedure. Following this multi-stage screening of titles, abstracts, and full texts, from a total of 1385 unique records, 48 studies were retained for synthesis.

For each entry, the following variables were collected where available: erosion rate (t ha−1 yr−1) or soil loss per mm of rain (t ha−1 mm−1), runoff coefficient (%), spatial location (country), plot size or spatial scale, measurement method, temporal scale (minutes, hours, event, years, decades), slope gradient (%), soil texture (sand, silt and clay %) and soil organic matter content (%) and soil conservation practices and vegetation cover (percentage of ground covered by herbaceous vegetation or cover crops in the inter-row areas).

To ensure comparability, data were categorized. Spatial scale was classified as: microplot (<2 m2), plot (2–1000 m2), and catchment (> 1000 m2). Measurement methods were grouped into: (i) rainfall simulation (RS), (ii) runoff plot (RP), (iii) flow and sediment gauge (FG), (iv) soil truncation (ST) such as FRN-based estimates and tree mound measurements, and (v) modelling (MOD). Soil conservation practices were classified as: (i) no-soil conservation practices (No-CP), including conventional tillage and no-tillage with herbicides/bare soil and (ii) soil conservation practices (CP) including cover crops (CC), reduced tillage (RT) and mulching (M) with materials like pruning residues.

For comparison reasons, soil loss rates in rainfall simulations (RS) are expressed per mm of simulated rainfall. It must be also noted that some runoff plot (RP) studies report soil loss rates at the event scale instead of yearly rates. For this reason, these rainfall simulation and event scale values are only used for relative comparisons, such as assessing soil loss and runoff reduction between No-CP and CP practices and should not be interpreted as representative of average annual soil loss.

2.2 Statistical analyses

Given the large variability in the collected data, statistical analyses were applied to identify the main trends regarding the effects of slope gradient, soil texture, organic matter, rain intensity and vegetation cover on soil loss and runoff. To reduce the uncertainty of comparing data from different methodologies, analyses were applied separately to data derived from distinct measurement methods (e.g., RS vs. RP). Ordinary least square linear (OLS) regression was used to examine the contribution of individual explanatory variables on the response variable. For this purpose, we used the Python library statsmodels (https://www.statsmodels.org, last access: 9 December 2025) to fit the model and examine the resulting coefficients (R2) and their significance (p-values). A higher coefficient (when standardized) means the variable has a greater impact on soil loss. In cases where model assumptions were violated, in particular when residuals are not normally distributed, a log-transform was applied to the dependent variable (soil loss rates or runoff coefficient).

The analysis of factors influencing soil loss and runoff generation was restricted to the RS and RP treatments. For the other treatments (ST, FG, and MOD), the available data was insufficient to perform a robust statistical analysis. This limitation arises from both the small number of published studies and the low total number of observations, even accounting for the fact that a single study can report multiple observations from different locations or experiments.

To validate the normality assumption of the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression, we examined the Omnibus and Jarque-Bera tests. These diagnostic metrics specifically assess the distribution of residuals; the Omnibus test combines skewness and kurtosis to detect deviations from normality, while the Jarque-Bera test determines if the sample data matches a normal distribution. A significant result (p<0.05) in these tests, often driven by high skewness (asymmetry in the data), indicated a violation of OLS assumptions, thereby confirming the necessity of the log-transformation. A log-transformation was applied to the dependent variables (soil loss rates or runoff coefficients) when model assumptions were violated – specifically non-normal residuals – or when low R2 values (<0.5) indicated high variability between studies. This transformation aimed to normalize residuals and improve the model's explanatory power. Multiple linear regression (MLR) models were also used to test the combined ability of several explanatory variables to predict the response variable. The coefficients from the model will indicate the relative influence of each variable. For all analyses, a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We also checked for multicollinearity (when independent variables are highly correlated). This was assessed by calculating the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for each predictor, ensuring that redundancy among variables did not inflate the standard errors or compromise the reliability of the regression coefficients.

3.1 Description of dataset

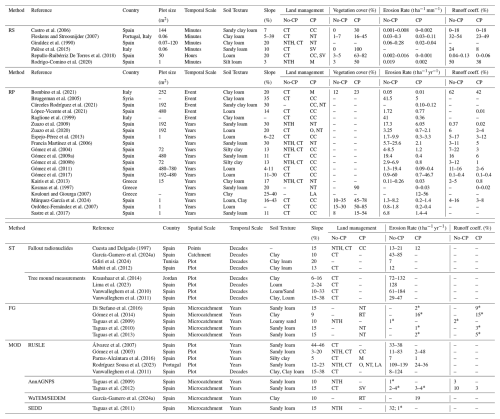

The literature search revealed that the vast majority of studies are concentrated in Spain, with far fewer in Italy, Greece, Portugal, Tunisia, Jordan and Syria (Fig. 4). The most frequently employed measurement method in the compiled literature is the runoff plot (RP), and the most common experimental design compares conventional tillage (CT) against various forms of soil conservation practices (CP), particularly groundcovers (Table 2). This focus in the literature underscores the scientific community's recognition of soil management as a critical variable. The most used model is RUSLE (Renard, 1997), followed by AnnANGPS (Bingner and Theurer, 2001), WaTEM/SEDEM (Van Oost et al., 2000) and SEDD (Ferro and Minacapilli, 1995). It must be noted that, while all modelling studies performed some level of performance assessment, none of the nine analysed studies conducted a complete, robust protocol involving both calibration and independent validation. The studies applying AnnAGNPS, WaTEM/SEDEM, and SEDD relied primarily on calibration (adjusting parameters to fit observed data) but did not report a subsequent independent validation. This was mainly attributed to the lack of observational records of sufficient duration to support distinct calibration and verification phases. Among the RUSLE studies, only 40 % were calibrated. For the remaining 60 % of uncalibrated applications, the reliability of the results was assessed through a “soft validation” by comparing model outputs with short-term observations from runoff plots or literature values.

Figure 4Geographical distribution of the reviewed studies. The numerical values indicate the number of studies per country (in blue).

Table 2Average single values or ranges (min–max) reported in the studies of the variables collected from published literature, if available. CT = Conventional tillage, NT = No tillage (with some vegetation cover), NTH = No tillage + Herbicides (no vegetation cover), CC = Cover crops, SV = Spontaneous vegetation, LA = Land abandonment, M = Mulching, O = Organic. No-CP = No-soil conservation (practices with no or very low ground/vegetation cover including CT and NTH); CP = Soil conservation practices (practices with some ground/vegetation cover including CC, NT, SV, M, LA). Empty cells (–) = Not applicable or Not reported. Some studies are included in two Methods because they report results for both categories. Please note that rainfall simulations erosion rates are in t ha−1 mm−1 of simulated rain and for Runoff plots in t ha−1 yr−1 with the exception of event scale results which are in t ha−1. * Sediment yield at the catchment outlet.

3.2 Average soil loss rates and runoff coefficients

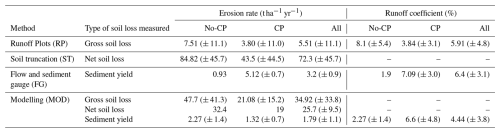

In Table 3 average erosion rates and runoff coefficients are grouped by method and type of soil loss measured. Average rates were calculated as the arithmetic mean of all independent observations collected for each methodology. This table highlights the wide range of values obtained by different approaches, reflecting differences in measurement scale, time period, and the distinction between gross, net soil loss and sediment yield.

Table 3Average erosion rates and runoff coefficients for Mediterranean olive groves, as reported in the literature. Values are grouped by method and type of soil loss measured and soil conservation practices (CP = Conservation practices). Standard deviations are shown in parentheses when more than one observed value is available. Empty cells (–) = Not Applicable or Not Reported.

The average annual soil loss rates vary by more than an order of magnitude, from as low as 1.8 t ha−1 yr−1 to as high as 72.3 t ha−1 yr−1. This is not a contradiction but a reflection of what each method measures. RP measure gross erosion (soil detachment and transport) from a small, defined area. It primarily captures interrill and some rill erosion. The average rate of 5.51 t ha−1 yr−1 is in line with Fleskens and Stroosnijder's (2007) who argue that soil loss in olive groves is generally below 10 t ha−1 yr−1. However, the large standard deviation (± 11.1) highlights the extreme variability based on site-specific conditions like slope, soil type, and rainfall patterns. Notably, average soil loss without conservation practices (No-CP) is 7.51 t ha−1 yr−1, but this value is reduced by about half when CP are implemented. In any case, these values are unsustainable and well above the tolerable soil loss rate, 0.3–1.4 t ha−1 yr−1, in Europe (Verheijen et al., 2009).

In ST studies, the exceptionally high value of 72.3 t ha−1 yr−1 represents the long-term net soil loss at a specific point on a hillslope, accumulated over decades or even centuries. This figure captures the cumulative impact of all major erosion processes, including both water erosion (interrill and rill) and, critically, tillage erosion, the progressive downslope movement of soil caused by repeated plowing. Such a high rate reflects the total historical degradation of the soil profile at that location, which explains why “alarming” values can appear in the literature. Importantly, this underscores the need to distinguish between gross and net soil loss, as well as to account for the substantial role of tillage erosion – often underestimated or overlooked in soil erosion research – even though it can surpass the effects of water erosion in many cultivated landscapes (Van Oost et al., 2006).

In FG, the relatively low value, 3.2 t ha−1 yr−1, measures sediment yield, the actual amount of eroded soil that exits an entire catchment. The vast difference between the average soil truncation rate (72 t ha−1 yr−1 of net soil loss) and the sediment yield (3.2 t ha−1 yr−1) indicates that while a massive amount of soil is being moved around within the olive grove landscape, much of it is redeposited at the bottom of slopes or in other landscape depressions and never reaches the stream network. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in Mediterranean catchments due to the prevalence of ephemeral stream networks that consist primarily of gullies and dry channels, which only become hydrologically connected during high-intensity rainfall events (Gómez et al., 2014; McLeod et al., 2024; Taguas et al., 2009). We also need to consider that most FG studies rely on automatic sampling of suspended sediment, often neglecting bedload transport. Therefore, while these values represent most of the export in fine-textured soils, they likely underestimate the total sediment load transferred through the stream network.

In MOD studies, gross soil loss (RUSLE) estimates of nearly 35 t ha−1 yr−1 (47.7 t ha−1 yr−1 with No-CP and 21.1 t ha−1 yr−1 with CP) align more closely with the high rates of landscape degradation suggested by soil truncation methods (e.g. (Vanwalleghem et al., 2011) rather than rates reported by runoff plots. The higher RUSLE value often stems from the model's application at broader scales with input parameters that may not perfectly reflect the conditions of a specific plot. For instance, topographic factors derived from digital elevation models can overestimate slope length and steepness, and the model's management factors (C and P) are notoriously difficult to calibrate accurately without site-specific data, often leading to an overestimation of erosion potential (Gómez et al., 2003). Indeed, some studies have explicitly found that theoretical models like USLE overestimate erosion rates when compared to direct empirical measurements in olive groves (Rodríguez Sousa et al., 2023). This gap between modelled potential and measured reality underscores a critical need for robust model calibration and validation using high-quality, long-term field data to improve predictive accuracy.

It is crucial to interpret the average values presented in Table 3 with caution, especially for those derived from ST, FG, and MOD studies. The body of literature reporting quantitative erosion and runoff rates using these specific methods in Mediterranean olive groves is still quite limited. Consequently, the averages are calculated from a small number of studies and data points. This scarcity means the mean values can be heavily skewed by single, site-specific results and may not fully represent the broader reality. Therefore, these figures should be seen as a preliminary snapshot, highlighting the need for more research to establish more robust and representative average rates.

The considerable variation in average soil loss rates reported across the different measurement methods reflects not only the diversity of processes captured but also the methodological limitations inherent to each approach.

RP artificial setup, bounded plots with restricted flow interactions, can lead to underestimation of actual runoff, since the contributing upslope or lateral flows are excluded. Moreover, the relatively short monitoring durations of many RP studies may miss rare but significant erosive events or overemphasize the conditions during a limited period. Despite these limitations, the wide use of RP in the literature provides a relatively robust, though still partial, representation of gross soil loss under plot-scale conditions.

ST estimates are associated with high uncertainty due to several critical assumptions that can also explain the large difference observed between FRN and tree mound estimates (Table 2). For FRNs, error often stems from the scarcity of undisturbed, proximal reference sites (García-Gamero et al., 2024a). In the case of olive tree mounds, uncertainty arises not only from the difficulty in distinguishing soil compaction from actual erosion but also from a lack of methodological consensus regarding the identification of the original soil surface. While the original approach (Vanwalleghem et al., 2010) proposed a soil marker, the highest point of the erosional mound, i.e. the top of the soil attached to the tree mound, later applications (Kourgialas et al., 2016; Lima et al., 2023) shifted to a biological marker, the transition between the trunk-mound transition, i.e. where the trunk gets wider. FG offer no insight into the specific sources of sediment: the measured material may originate from olive groves, but also from unrelated sources such as gully erosion, bank collapse, or landslides. Additionally, the small number and limited duration of FG studies limit the representativeness of the results, especially in Mediterranean landscapes with highly variable rainfall regimes.

MOD results are contingent on the quality and resolution of input data and the rigor of calibration/validation procedures. In olive systems, where specific empirical data is scarce, most studies rely on calibration alone – omitting independent validation – or depend on generalized regional parameters that may not reflect local reality. Moreover, the use of average weather data can obscure the impact of extreme events, which play a crucial role in Mediterranean erosion dynamics. As such, model results should be interpreted as approximate, order-of-magnitude estimates rather than precise measurements.

Runoff coefficients are fairly similar (∼ 4 %–6 %) across the various methods. This suggests that the fraction of rainfall becoming surface runoff is moderately low in Mediterranean olive groves, consistent with soil infiltration capacity and episodic storms. It also implies that differences in erosion rates are not due to differences in runoff volume, but rather in how much soil is detached per unit runoff (influenced by cover, tillage, slope, etc.). In practice, extreme storm events can drive much higher instantaneous runoff and erosion than these average coefficients indicate.

This data also highlights the effectiveness of conservation practices (CP) in reducing soil loss and runoff. We calculated these reduction averages using only paired data (direct side-by-side comparisons of CP versus No-CP under identical conditions) to isolate the true impact. In terms of how effective CP are in reducing soil loss and runoff generation, RS show the highest reduction rates, 89 % for soil loss and 66 % for runoff. These controlled, small-scale experiments are able to isolate the direct protective effect of a ground cover against raindrop impact (splash erosion), which is the first stage of erosion. The nearly 90 % reduction in soil loss underscores the immense potential of CP to shield the soil surface. RP, which measure erosion under natural rainfall over longer periods, show a still massive, but slightly lower, reduction: 68 % for soil loss and 34 % for runoff. This reflects real-world conditions where factors like variable rainfall and larger-scale water flow come into play. A key insight is that CP is significantly more effective at reducing soil loss than it is at reducing runoff volume. This indicates that the primary benefit of ground cover is preventing soil particles from being detached and carried away. While it also improves infiltration (reducing runoff), its main role is to protect the soil and slow the water flow, drastically reducing the water's capacity to transport sediment.

3.3 Statistical analysis of erosion drivers

3.3.1 Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression

Slope

The only statistically significant correlation (p-value < 0.05) was observed in RS and only with the soil loss rate (per mm of rain). The OLS regression analysis confirmed a low positive relationship between erosion rate and slope gradient. However, the diagnostic tests (Omnibus, Jarque-Bera, Skew) indicated that the assumptions of the OLS model have been violated, specifically the assumption of normally distributed errors. Therefore, a log-transform of the soil loss variable (dependent variable) was applied. The log transformation successfully addressed the violation of the normality assumption. However, the model's explanatory power is relatively low, explaining only 16.7 % of the variance in the log of soil loss. Despite this, the relationship between slope and soil loss remained statistically significant. Olive groves are often on steep slopes, which inherently increases the risk and rate of erosion. On very steep slopes, the gradient can be the dominant factor, overriding management effects. However, these findings do not indicate this strong influence, at least by considering the slope alone.

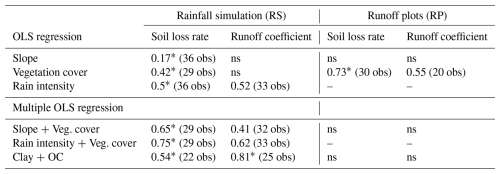

Table 4Summary of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) and Multiple OLS regression results showing the influence of different factors on soil loss rate and runoff coefficient. The table presents the coefficient of determination (R2) for models based on data from Rainfall Simulation (RS) and Runoff Plot (RP) studies. “ns” denotes a non-significant result. The number of observations (obs) is given in parentheses. An asterisk (*) indicates a that log-transformation was applied to the dependent variables (soil loss rate or runoff coefficient) to ensure normally distributed residuals. Empty cells (–) = Not Applicable or Not Reported.

Vegetation cover

In the rainfall simulation (RS) studies, vegetation cover on its own explained 42 % of the variance in the log of soil loss (R2=0.42 after log-transform; 29 observations). This moderate negative but significant relationship highlights the immediate, local effects of vegetation. At this scale, the primary mechanism is the reduction of raindrop impact energy by the plant canopy, which minimizes the detachment of soil particles (splash erosion), a foundational step in the erosion process (Panagos et al., 2015). Interestingly, vegetation cover showed no statistically significant influence on the runoff coefficient in these experiments. This is likely due to the nature of rainfall simulators, which apply high-intensity rainfall over a small area for a short duration. These conditions can quickly saturate the topsoil, causing infiltration capacity to be exceeded regardless of cover, thus generating similar runoff volumes across different plots.

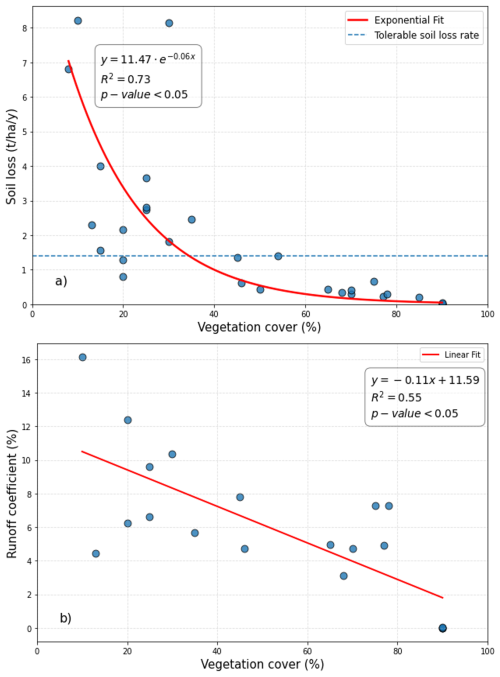

The results from runoff plot (RP) studies provide further evidence of this protective effect. Here, vegetation cover alone accounted for a remarkable 73 % of the variance in the log of soil loss (R2=0.73 after log-transform; 30 observations; Fig. 5a). This demonstrates that over larger areas than RS and under natural rainfall conditions, the cumulative effects of vegetation become much more pronounced. Furthermore, at this scale, vegetation cover also explained 55 % of the variance in the runoff coefficient (R2=0.55; 20 observations; Fig. 5b). This contrasts sharply with the RS results and shows that vegetation cover is effective at reducing the total volume of runoff. This is because, over time, groundcover and its associated root systems improve soil structure, enhance aggregation, and increase macroporosity, all of which significantly boost the soil's overall infiltration capacity (Keesstra et al., 2018; Gómez et al., 2009a). More water entering the soil profile directly translates to less water available to generate surface runoff. The need for a log-transformation for the annual soil loss model indicates a right-skewed distribution which is in line with previous studies that suggest that there is a critical threshold of vegetation cover (Liu et al., 2020; Sastre et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2022). Below a certain percentage of cover, the soil is highly vulnerable. Above this threshold, erosion rates can decrease dramatically. The RP data indicates that this threshold is 30 %–40 %, below which the soil loss rate is above the tolerable rate in Europe, 1.4 t ha−1 yr−1 (Verheijen et al., 2009).

Figure 5Runoff plot studies – Relationship between vegetation cover and: (a) soil loss rate and (b) runoff coefficient. Each point represents a single plot measurement. The red line represents the best fit line. The dashed line represents the tolerable soil loss rate in Europe (Verheijen et al., 2009). In Fig. 3a, the regression model was fitted to log-transformed data, but data is plotted on a linear scale with the resulting exponential curve for interpretability and for consistency with Fig. 5b.

Rainfall intensity

The rainfall intensity is factor only considered in RS, this factor can be controlled, and it is usually kept constant during the rainfall simulations. In contrast, in RP the rainfall is natural and hence, highly variable during the period of study. The regression analysis confirmed a positive relationship between erosion rate and rain intensity of the rainfall simulations. However, the diagnostic tests indicated that the assumption of normally distributed errors is not correct. Applying a log transformation created an accurate and statistically valid model (R2=0.50 with 36 observations) with nearly 50 % of the variability in the log of soil loss per mm of rain being explained by rainfall intensity.

The statistical result is a direct reflection of the kinetic energy of rainfall. Higher intensity rainfall has significantly more kinetic energy, resulting in the detachment of a greater volume of soil particles, a process known as splash erosion. Moreover, more intense rain generates runoff more quickly and in greater volumes. A study by van Dijk et al. (2002) reviewed various rainfall erosivity models and confirmed that kinetic energy and rainfall intensity are the most effective predictors of splash detachment and interrill soil erosion. They highlighted that the relationship is often non-linear, which aligns with why a log transformation improved the statistical model in this analysis.

3.3.2 Multiple linear regression (MLR)

While all potential variable combinations were evaluated, only those yielding statistically significant results are presented.

Slope + Vegetation cover

By combining slope with vegetation cover, after a log-transform to address non-normal residuals, the MLR model explained 65 % (RS) of the variance in the log of soil loss. Both slope and vegetation cover were highly significant predictors. This strong influence of the combined effects of slope and vegetation cover highlights their synergistic control on soil loss. The model that only considered slope was statistically weak because it omitted the crucial protective role of vegetation. Vegetation intercepts rainfall, reducing its erosive energy, and increases infiltration, which reduces the volume of runoff. By increasing surface roughness, it also reduces the velocity and shear stress of the runoff that does occur. The result is that for the same slope and storm, the erosive force is drastically lower on a vegetated plot compared to a bare one. This explains why a simple model considering only slope is insufficient; the effect of slope is contingent on the condition of the surface. While this interaction indicates a statistical synergy, the strong correlation is likely driven heavily by the influence of vegetation cover.

Vegetation + Rain intensity

Combining vegetation cover with rain intensity in RS, the MLR model explained 75 % of the variance in the log of soil loss per mm of rain (R2=0.75 after log-transform; 29 observations) and 62 % of the variance in the runoff coefficient (R2=0.62; 29 observations). These results demonstrate that the published data represent the fundamental conflict between the erosive force of rainfall and the protective resistance of vegetation. While high-intensity simulations can mask the influence of vegetation on runoff when viewed in isolation, combining it with the intensity variable reveals its persistent and significant role in mitigating both the volume of runoff and, most critically, the detachment and transport of soil particles. This highlights the necessity of a multi-factor approach to accurately model hydrological and erosional responses under the specific conditions of rainfall simulation. Moreover, these results also demonstrate the resilience and protective effect of vegetation cover even under extreme high-intensity conditions of RS.

Studies show that soil erosion (total sediment yield) is reduced much more effectively by plant covers than is runoff volume (Cárceles Rodríguez et al., 2021). This disparity means the sediment concentration in runoff is significantly lower under conservation practices, even if runoff volume is not completely eliminated. The physical protection offered by the cover crops is a primary mechanism for reducing sediment detachment, while infiltration/runoff processes are more complex and site-dependent.

Soil texture + OC

For both, RS and RP the soil texture factors (sand (%), silt (%), clay (%)) and OC (%) did not show statistically significant results in the regression analysis. However, for RS when these factors were combined in a MLR model the results drastically improved. The best results were obtained when combining clay and OC. The model was then highly significant and explained 53.9 % (R2=0.54 after log-transform with 25 observations) of the variance in the log of soil loss (per mm of rain) and 80.8 % (R2=0.81 after log-transform with 25 observations) of the variance in the runoff coefficient. The results indicate that increased “clay” content is associated with a percentage increase in soil loss and runoff (positive relationship), while increased “OC” is associated with a percentage decrease in soil loss and runoff (negative relationship).

Soil texture influences properties like saturated hydraulic conductivity (Ksat) and compaction potential (Bombino et al., 2021). Clayey soils depleted in organic matter, often found in Mediterranean olive groves, can saturate quickly and have low Ksat, making them prone to runoff, especially on steep slopes. Bare soil conditions and conventional tillage can exacerbate these issues by degrading soil structure, leading to increased compaction and surface sealing, which reduces infiltration in soils regardless of texture, but particularly impacting clayey soils (Gómez et al., 2009b; Palese et al., 2015).

This shows that soil composition has a significant impact on soil loss: higher clay content increases erosion and runoff, while higher organic carbon content dramatically reduces them. Mediterranean olive soils often have low OC, so improving organic matter significantly lowers erosion. Again, an increase in vegetation cover (e.g. through cover crops) can initiate a positive feedback loop by directly increasing the soil's organic carbon content. Therefore, promoting vegetation cover is not just a surface-level protection strategy; it is a fundamental method for rebuilding the soil's intrinsic health and resilience from within.

Soil erosion is an inherently scale-dependent process, and no single method or metric can capture its full complexity. The ongoing debate between “alarmist” and “non-alarmist” interpretations (Fleskens and Stroosnijder, 2007; Gómez et al., 2008) of erosion severity is, at its core, a debate about the scale of truth. Different measurement methods target different parts (Fig. 6) of the erosion–transport–deposition continuum, leading to conflicting figures that are, in fact, complementary. To develop a realistic and comprehensive understanding of soil erosion, particularly in agricultural landscapes, it is essential to adopt a multi-method, multi-scale approach. Each method provides a partial view, thus reveals a different “truth”, emphasizing different spatial and temporal aspects of erosion dynamics:

-

Runoff plots measure what's being mobilized. Runoff plot studies are ideal for capturing gross soil loss in upslope areas where contributing areas are small and deposition minimal (Francia Martínez et al., 2006; Gómez et al., 2004). These plots are valuable for comparing land management practices and assessing soil susceptibility to detachment. However, they only represent the initial phase of the erosion process and typically underestimate the cumulative effects of long-term processes like tillage erosion or gully expansion.

-

Soil truncation methods measure what's lost or displaced over time. They provide spatially distributed, long-term estimates of net soil loss across entire hillslopes or catchments (Kraushaar et al., 2014; Vanwalleghem et al., 2011). These techniques capture both water and tillage erosion and are particularly suited for detecting cumulative soil displacement over decades. While they may miss the process of gully formation, they offer a more realistic picture of landscape-scale degradation and on-site impacts.

-

Sediment and flow gauges at the catchment outlet measure what's exported, the final output of the erosion system and final stage of the erosion cascade (Taguas et al., 2013). These data integrate all upstream erosion processes but often register lower values than total soil loss because much of the mobilized sediment is trapped within the landscape, stored in footslopes, depressions, gully systems, and floodplains, before it is exported from the catchment. This scenario, however, changes dramatically during high-intensity rainfall events (Gómez et al., 2014), which can connect the drainage network and trigger severe gully erosion, leading to major sediment export. Sediment yield is critical for evaluating off-site impacts, such as reservoir siltation or pollutant transport, but it does not reflect the full extent of on-site soil degradation.

Figure 6Conceptualization of a typical catchment hillslope and what parts and stages are characterized by the different soil erosion measurement methods.

Models, when properly calibrated and validated, serve as critical tools for bridging these scales and for conducting future scenario analysis. However, their reliability depends on the availability of multi-decadal observational data, which is essential to ensure observational records of sufficient duration to support distinct calibration and verification phases and to capture the long-term influence of land management on erosion dynamics. Soil truncation estimates, derived from Fallout Radionuclides (FRNs) or tree mound measurements, provide this necessary long-term data, yet they carry inherent uncertainties that are frequently overlooked (see Sect. 3.2). These inconsistencies not only reduce the precision of the erosion estimates themselves but also propagate uncertainty into the model calibration process, potentially undermining the reliability of long-term simulations. This creates a challenging feedback loop: models cannot be reliably validated without robust, long-term field data, and the available long-term field data remain uncertain. Therefore, the scientific community must prioritize generating a larger volume of long-term estimates while rigorously standardizing these methodologies to reduce uncertainty. Only by securing “more and better” calibration data can we ensure that model projections accurately reflect future erosion risks.

Sediment fingerprinting (Davis and Fox, 2009) and radiometric dating of deposited sediments (Smith et al., 2018) are methodologies not applied in the reviewed studies, but which could nonetheless provide valuable long-term information. Sediment fingerprinting primarily yields estimates of relative sediment source contributions rather than absolute soil loss rates; however, when combined with radiometric dating of depositional archives, it has the potential to link erosional processes across different spatial and temporal scales. Despite this potential, their application in Mediterranean olive groves is subject to important limitations. A key constraint is the scarcity of stable, long-term sedimentary archives: with the exception of water reservoirs, permanent water bodies are rare in these semi-arid landscapes, while alternative depositional environments, such as footslopes or alluvial fans, are frequently disturbed by tillage or re-incised by active gullying (Leenman and Eaton, 2022). Moreover, the widespread occurrence of gully erosion complicates the use of methods such as fallout radionuclides (FRNs). Gullies mobilize deep subsoil that is depleted in FRNs, generating a “dilution effect” that can obscure the signal of topsoil erosion in depositional zones. Consequently, observed sedimentation rates may be dominated by episodic channel or gully incision rather than reflecting diffuse hillslope erosion processes. Further research is therefore required to evaluate the feasibility, reliability, and methodological adaptations needed for applying sediment fingerprinting and radiometric approaches in Mediterranean olive grove catchments.

Ultimately, embracing a multi-scale, integrated approach is not just a methodological choice, it's a necessity. It allows us to capture both the localized detachment and the landscape-level sediment delivery and is critical for the design of effective soil conservation strategies and for the calibration and validation of erosion models. For example, in upslope areas close to the catchment boundaries, where deposition and the upslope contributing area are minimal (net soil loss closely approximated gross soil detachment), we could consider combining runoff plot estimates (representing gross soil loss due to water erosion) with soil truncation estimates (representing net soil loss due to both water and tillage erosion). The difference between the net soil loss (derived from soil truncation methods) and the gross soil loss (derived from runoff plots) in the same location could provide an inference of the tillage erosion contribution. This is because soil truncation methods inherently capture the cumulative effects of both water and tillage erosion over longer timescales, while runoff plots primarily isolate the detachment and transport by water. This can be conceptually represented as:

However, comparing multi-decadal ST data with short-term RP data carries a significant temporal mismatch, primarily because short-term plots often miss the extreme events that log-term ST captures. Nevertheless, this conceptual comparison becomes quantitatively more robust in specific scenarios where timescales align – for instance, when mound measurements are taken on younger trees (e.g., <20 years) that match the duration of long-term runoff studies. This would help to disentangle the significant, yet often overlooked, role of tillage in overall soil displacement within agricultural landscapes as well as to calibrate and evaluate tillage erosion models. Only by acknowledging the complexity and scale-dependency of soil erosion can we resolve inconsistencies in the literature and move toward more sustainable land management.

Yet, this scientific understanding uncovers a critical paradox in olive cultivation, a “silent crisis” where olive yields have increased, mainly driven by the mechanization of cultivation and the increase of tree density (Amate et al., 2013), despite increasing long term soil erosion and ongoing degradation (Peñuela et al., 2023). The ability of deep soils to buffer initial losses, combined with management practices such as enhanced fertilization, pruning, and pest control, has effectively masked the unsustainability of current practices (Tubeileh et al., 2014). This absence of a negative impact on yield has meant there's been no immediate or direct incentive for farmers to adopt soil management practices that prioritize conservation, allowing prolonged unsustainable practices to continue. The current system is drawing down a vital natural capital, soil, without immediate visible consequences, but with severe long-term implications for future generations. This situation urgently calls for a fundamental paradigm shift in how agricultural success is defined and measured, emphasizing long-term ecological resilience alongside productivity. Therefore, policy and farmer education must move beyond short-term yield metrics to incorporate and prioritize long-term soil health indicators such as the Soil Footprint (García-Gamero et al., 2024b).

The evidence supports that increasing vegetation/ground cover between olive trees as the most effective strategy for erosion control in olive groves. Their multifaceted benefits, including significant erosion reduction, enhanced infiltration, increased organic matter content, and improved soil aggregation, simultaneously address several key drivers of degradation (Gómez et al., 2009a, b; Márquez-García et al., 2024; Repullo-Ruibérriz De Torres et al., 2018). Despite the acknowledged challenge of water competition, the magnitude of erosion reduction achieved suggests that the benefits often outweigh the risks, especially with careful species selection and adaptive management (Gómez et al., 2009b). Even the “non-alarmist” average gross soil loss rates measured in runoff plots (5.5 t ha−1 yr−1) exceed the upper limit of tolerable loss (0.3–1.4 t ha−1 yr−1; Verheijen et al., 2009) by nearly 400 %. This implies that soil conservation practices such as cover crops are not merely “an option” but represent a fundamental requirement for achieving long-term sustainability in Mediterranean olive groves (Bombino et al., 2021). Therefore, policy incentives and research efforts should prioritize the widespread adoption and optimization of soil conservation strategies, including the development of drought-tolerant cover crops species and adaptive management strategies designed to minimize water competition during critical dry periods.

Further research integrating multi-scale or multi-proxy field monitoring with robust model calibration and validation across a wider range of environmental and management conditions is essential to accurately quantify erosion risks and develop effective and sustainable soil management strategies for Mediterranean olive groves. The path to sustainable olive cultivation lies in a paradigm shift towards evidence-based management strategies. Prioritizing soil conservation strategies, minimizing intensive tillage and maximizing vegetation/ground cover are paramount. These practices not only effectively reduce soil and nutrient loss but also enhance soil health and resilience. However, successful adoption hinges on addressing socio-economic barriers, including perceived water competition, management costs, and traditional biases (Rodrigo-Comino et al., 2020; Sastre et al., 2017).

In this context, policy support becomes a decisive factor in shifting current management paradigms toward more sustainable practices. Conservation Agriculture (CA) (Gonzalez-Sanchez et al., 2015), through its emphasis on permanent groundcovers and no tillage (FAO, 2022), offers a robust framework for mitigating erosion and restoring soil functionality in Mediterranean perennial systems such as olive groves. Despite the clear effectiveness of cover crops in reducing erosion rates (often by an order of magnitude, see Table 2), widespread adoption remains limited, with over 50 % of the olive-growing area in major producing countries like Spain still maintained as bare soil (MAPA, 2024). Consequently, successful implementation requires adequate training, cross-compliance mechanisms, incentives, regulatory support, and integration into agricultural subsidy frameworks. The successful implementation of CA requires not only technical knowledge but also institutional alignment and policy coherence at local and national levels. Cross-compliance serves as the necessary regulatory baseline, ensuring that eligibility for public support is conditional upon avoiding the most harmful practices, such as maintaining bare soil on steep slopes. This “compliance push” creates a universal minimum standard. Simultaneously, financial incentives – such as eco-schemes under the Common Agricultural Policy – provide the necessary “economic pull”, compensating farmers for the opportunity costs and technical risks associated with adopting active conservation strategies. In regions where olive cultivation is dominant, promoting CA through targeted programs can serve as a powerful lever to reduce erosion, combat desertification, and strengthen the resilience of rural landscapes.

This literature review has synthesized a broad spectrum of research spanning from plot-scale field experiments to catchment-level monitoring and long-term soil truncation estimates. These are the main conclusions:

-

While natural factors such as topography, rainfall and soil properties establish a baseline risk, the evidence is unequivocal that agricultural management is the pivotal factor controlling soil degradation.

-

The magnitude of soil erosion is highly methodology-dependent, reconciling conflicting literature: while catchment yields are low due to redeposition, long-term soil truncation reveals unsustainable net losses (∼ 72.3 t ha−1 yr−1) that far exceed plot-scale estimates (<10 t ha−1yr−1) by capturing cumulative processes like tillage erosion and extreme events often missed by short-term monitoring. There is a critical need for multi-scale and multi-proxy approaches studies, as no single method can capture the full complexity of erosion in agricultural catchments.

-

The data consistently show that while steep slopes, intense rainfall, and soil properties (texture and organic carbon content) create the potential for erosion, the presence of vegetation cover is the decisive control. Conservation practices, such as cover crops, reduce soil loss by more than half. This effect is far more pronounced for soil loss than for runoff.

-

The data indicates that there is a vegetation cover threshold of 30 %–40 %, below which the soil loss rate is above the tolerable rate in Europe, 1.4 t ha−1 yr−1 and increases exponentially.

-

The average runoff coefficient remaining relatively low and consistent at 5 %–6 % across different measurement methods. This indicates that the primary benefit of ground cover is protecting the soil surface and preventing particle detachment, rather than solely reducing water volume.

-

While vegetation cover is the most important management factor, the inherent properties of the soil are a primary driver of how it responds to rainfall. A soil with low organic carbon and a texture prone to surface sealing (like degraded clay soils) is at a much higher baseline risk of severe erosion and runoff.

-

Finally, this review highlights a significant gap between modelled potential and measured reality. Models like RUSLE simulate considerably higher soil loss rates than those measured in runoff plots. This discrepancy underscores the urgent need for better model calibration and validation using robust, long-term field data to improve the accuracy of our predictive tools.

In summary, current evidence suggests that shifting towards permanent ground cover is a viable strategy for sustainability. This requires a shift away from conventional bare-soil management towards the widespread adoption of conservation practices that maintain permanent ground cover. The challenge is not a lack of technical solutions but one of implementation, which must be driven by effective policies and a continued commitment to integrated, multi-scale research.

The Python code used for the statistical analysis is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17952722 (Peñuela and Milazzo, 2025).

Data used in this study is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17952722 (Peñuela and Milazzo, 2025).

AP and FM conducted the data curation, which included the collection, filtering, and processing of reviewed studies, and performed the subsequent statistical analysis. AP was responsible for the study's conceptualization and the primary interpretation of the results. EGS contributed to the manuscript writing and the interpretation of the findings.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policy of the European Union or the European Research Executive Agency (REA).

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This publication was funded by the European Union's Horizon Europe Research and Innovation Programme, under the iMPACT-erosion project (Grant agreement No. 101062258), the TRAILS4SOIL project (Grant Agreement No. 101218949) and the Soil Mission's MONALISA project (Grant Agreement No. 101157867). The authors gratefully acknowledge the collaboration of all project partners and participating stakeholders.

This research has been supported by the European Research Executive Agency (grant no. 101062258) and by the TRAILS4SOIL project (grant no. 101218949).

This paper was edited by Olivier Evrard and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Álvarez, S., Soriano, M. A., Landa, B. B., and Gómez, J. A.: Soil properties in organic olive groves compared with that in natural areas in a mountainous landscape in southern Spain, Soil Use Manag., 23, 404–416, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-2743.2007.00104.x, 2007.

Amate, J. I., De Molina, M. G., Vanwalleghem, T., Fernández, D. S., and Gómez, J. A.: Erosion in the Mediterranean: The Case of Olive Groves in the South of Spain (1752–2000), Environ. Hist., 18, 360–382, https://doi.org/10.1093/envhis/emt001, 2013.

Bingner, R. and Theurer, F.: AnnAGNPS: estimating sediment yield by particle size for sheet and rill erosion, in: Proceedings of the 7th Interagency Sedimentation Conference, 2001.

Boix-Fayos, C., Martínez-Mena, M., Arnau-Rosalén, E., Calvo-Cases, A., Castillo, V., and Albaladejo, J.: Measuring soil erosion by field plots: Understanding the sources of variation, Earth-Sci. Rev., 78, 267–285, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2006.05.005, 2006.

Bombino, G., Denisi, P., Gómez, J. A., and Zema, D. A.: Mulching as best management practice to reduce surface runoff and erosion in steep clayey olive groves, Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res., 9, 26–36, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iswcr.2020.10.002, 2021.

Bruggeman, A., Masri, Z., Turkelboom, F., Zöbisch, M., and El-Naeb, H.: Strategies to sustain productivity of olive groves on steep slopes in the northwest of the Syrian Arab Republic, in: The role and importance of integrated soil and water management for orchard development: Proceedings of the International Seminar, edited by: Benites, J., Pisante, M., and Stagnari, F., FAO Land and Water Bulletin No. 10, 75–87, 2005.

Cárceles Rodríguez, B., Zuazo, V. H. D., Rodríguez, M. S., Ruiz, B. G., and García-Tejero, I. F.: Soil Erosion and the Efficiency of the Conservation Measures in Mediterranean Hillslope Farming (SE Spain), Eurasian Soil Sc., 54, 792–806, https://doi.org/10.1134/S1064229321050069, 2021.

Castro, G., Romero, P., Gómez, J. A., and Fereres, E.: Rainfall redistribution beneath an olive orchard, Agricultural Water Management, 86, 249–258, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2006.05.011, 2006.

Cuesta, M. J. C. and Delgado, A.: Comparación de procesos erosivos en suelos agrícolas mediante el radioisótopo Cesio-137, ITEA, 93, 65–73, 1997.

Davis, C. M. and Fox, J. F.: Sediment Fingerprinting: Review of the Method and Future Improvements for Allocating Nonpoint Source Pollution, J. Environ. Eng., 135, 490–504, https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9372(2009)135:7(490), 2009.

De Vente, J. and Poesen, J.: Predicting soil erosion and sediment yield at the basin scale: Scale issues and semi-quantitative models, Earth-Sci. Rev., 71, 95–125, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2005.02.002, 2005.

Di Stefano, C., Ferro, V., Burguet, M., and Taguas, E. V.: Testing the long term applicability of USLE-M equation at a olive orchard microcatchment in Spain, CATENA, 147, 71–79, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2016.07.001, 2016.

Espejo-Pérez, A. J., Rodríguez-Lizana, A., Ordóñez, R., and Giráldez, J. V.: Soil Loss and Runoff Reduction in Olive-Tree Dry-Farming with Cover Crops, Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J., 77, 2140–2148, https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2013.06.0250, 2013.

FAO: Conservation Agriculture, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, Italy, https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/024e17be-9fad-4556-be94-a8e2f229023d/content (last access: 30 January 2026), 2022.

Ferro, V. and Minacapilli, M.: Sediment delivery processes at basin scale, Hydrol. Sci. J., 40, 703–717, 1995.

Fleskens, L. and Stroosnijder, L.: Is soil erosion in olive groves as bad as often claimed?, Geoderma, 141, 260–271, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2007.06.009, 2007.

Francia Martínez, J. R., Durán Zuazo, V. H., and Martínez Raya, A.: Environmental impact from mountainous olive orchards under different soil-management systems (SE Spain), Sci. Total Environ., 358, 46–60, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.05.036, 2006.

García-Gamero, V., Mas, J. L., Peñuela, A., Hurtado, S., Peña, A., and Vanwalleghem, T.: Assessment of soil redistribution rates in a Mediterranean olive orchard in South Spain using two approaches: 239+240Pu and soil erosion modelling, CATENA, 241, 108052, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2024.108052, 2024a.

García-Gamero, V., Vanwalleghem, T., and Peñuela, A.: Soil footprint: A simple indicator to communicate and quantify soil security, Soil Secur., 16, 100156, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soisec.2024.100156, 2024b.

Gdiri, A., Ben Cheikha, L., Oueslati, M., Saiidi, S., and Reguigui, N.: Investigating soil erosion using cesium-137 tracer under two different cultivated lands in El Kbir watershed, Tunisia, Euro-Mediterr. J. Environ. Integr., 9, 783–796, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41207-024-00497-0, 2024.

Giraldez, J. V., Carrasco, C., Otten, A., Ietswaart, H., Laguna, A., and Pastor, M.: The control of soil erosion in olive orchards under reduced tillage, in: Seminar on interaction between agricultural systems and soil conservation in the Mediterranean Belt, European Society for Soil Conservation, 1990.

Gómez, J. A., Battany, M., Renschler, C. S., and Fereres, E.: Evaluating the impact of soil management on soil loss in olive orchards, Soil Use Manag., 19, 127–134, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-2743.2003.tb00292.x, 2003.

Gómez, J. A., Romero, P., Giráldez, J. V., and Fereres, E.: Experimental assessment of runoff and soil erosion in an olive grove on a Vertic soil in southern Spain as affected by soil management, Soil Use Manag., 20, 426–431, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-2743.2004.tb00392.x, 2004.

Gómez, J. A., Giráldez, J. V., and Vanwalleghem, T.: Comments on “Is soil erosion in olive groves as bad as often claimed?” by L. Fleskens and L. Stroosnijder, Geoderma, 147, 93–95, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2008.07.006, 2008.

Gómez, J. A., Sobrinho, T., Giraldez, J., and Fereres, E.: Soil management effects on runoff, erosion and soil properties in an olive grove of Southern Spain, Soil Tillage Res., 102, 5–13, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2008.05.005, 2009a.

Gómez, J. A., Guzmán, M. G., Giráldez, J. V., and Fereres, E.: The influence of cover crops and tillage on water and sediment yield, and on nutrient, and organic matter losses in an olive orchard on a sandy loam soil, Soil Tillage Res., 106, 137–144, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2009.04.008, 2009b.

Gómez, J. A., Llewellyn, C., Basch, G., Sutton, P. B., Dyson, J. S., and Jones, C. A.: The effects of cover crops and conventional tillage on soil and runoff loss in vineyards and olive groves in several Mediterranean countries, Soil Use and Management, 27, 502–514, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-2743.2011.00367.x, 2011.

Gómez, J. A., Vanwalleghem, T., De Hoces, A., and Taguas, E. V.: Hydrological and erosive response of a small catchment under olive cultivation in a vertic soil during a five-year period: Implications for sustainability, Agric. Ecosyst. Environ., 188, 229–244, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2014.02.032, 2014.

Gómez, J. A., Francia, J. R., Guzmán, G., Vanwalleghem, T., Durán Zuazo, V. H., Castillo, C., Aranda, M., Cárceles, B., Moreno, A., Torrent, J., and Barrón, V.: Lateral Transfer of Organic Carbon and Phosphorus by Water Erosion at Hillslope Scale in Southern Spain Olive Orchards, Vadose Zone J., 16, 1–15, https://doi.org/10.2136/vzj2017.02.0047, 2017.

Gonzalez-Sanchez, E. J., Veroz-Gonzalez, O., Blanco-Roldan, G. L., Marquez-Garcia, F., and Carbonell-Bojollo, R.: A renewed view of conservation agriculture and its evolution over the last decade in Spain, Soil Tillage Res., 146, 204–212, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2014.10.016, 2015.

Huber, S., Prokop, G., Arrouays, D., Banko, G., Bispo, A., Jones, R. J. A., Kibblewhite, M., Lexer, W., Moller, A., Rickson, R. J., Shishkov, T., Stephens, M., Toth, G., Van Den Akker, J., Varallyay, G., and Verheijen, F.: Environmental Assessment of Soil for Monitoring Volume I: Indicators & Criteria, EUR 23490 EN/1, OPOCE, Luxembourg, https://doi.org/10.2788/93515, 2008.

ISMEA: Scheda di settore – Olio di oliva, Agosto 2025, Istituto di Servizi per il Mercato Agricolo Alimentare, https://www.ismeamercati.it/flex/files/1/6/f/D.cff78df6f341746db73f/Scheda_OLIO_agosto_2025.pdf (last access: 30 January 2026), 2025.

Kairis, O., Karavitis, C., Kounalaki, A., Salvati, L., and Kosmas, C.: The effect of land management practices on soil erosion and land desertification in an olive grove, Soil Use and Management, 29, 597–606, https://doi.org/10.1111/sum.12074, 2013.

Keesstra, S., Nunes, J., Novara, A., Finger, D., Avelar, D., Kalantari, Z., and Cerdà, A.: The superior effect of nature based solutions in land management for enhancing ecosystem services, Sci. Total Environ., 610–611, 997–1009, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.08.077, 2018.

Kosmas, C., Danalatos, N., Cammeraat, L. H., Chabart, M., Diamantopoulos, J., Farand, R., Gutierrez, L., Jacob, A., Marques, H., Martinez-Fernandez, J., Mizara, A., Moustakas, N., Nicolau, J. M., Oliveros, C., Pinna, G., Puddu, R., Puigdefabregas, J., Roxo, M., Simao, A., Stamou, G., Tomasi, N., Usai, D., and Vacca, A.: The effect of land use on runoff and soil erosion rates under Mediterranean conditions, CATENA, 29, 45–59, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0341-8162(96)00062-8, 1997.

Koulouri, M. and Giourga, C.: Land abandonment and slope gradient as key factors of soil erosion in Mediterranean terraced lands, CATENA, 69, 274–281, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2006.07.001, 2007.

Kourgialas, N. N., Koubouris, G. C., Karatzas, G. P., and Metzidakis, I.: Assessing water erosion in Mediterranean tree crops using GIS techniques and field measurements: the effect of climate change, Nat. Hazards, 83, 65–81, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-016-2354-5, 2016.

Kraushaar, S., Herrmann, N., Ollesch, G., Vogel, H.-J., and Siebert, C.: Mound measurements – quantifying medium-term soil erosion under olive trees in Northern Jordan, Geomorphology, 213, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2013.12.021, 2014.

Leenman, A. S. and Eaton, B. C.: Episodic sediment supply to alluvial fans: implications for fan incision and morphometry, Earth Surf. Dyn., 10, 1097–1114, https://doi.org/10.5194/esurf-10-1097-2022, 2022.

Lima, F., Blanco-Sepúlveda, R., Calle, M., and Andújar, D.: Reconstruction of historical soil surfaces and estimation of soil erosion rates with mound measurements and UAV photogrammetry in Mediterranean olive groves, Geoderma, 440, 116708, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2023.116708, 2023.

Liu, Y.-F., Liu, Y., Shi, Z.-H., López-Vicente, M., and Wu, G.-L.: Effectiveness of re-vegetated forest and grassland on soil erosion control in the semi-arid Loess Plateau, CATENA, 195, 104787, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2020.104787, 2020.

López-Cuervo, S.: La erosión en los suelos agrícolas y forestales de Andalucía, Colección: Congresos y Jornadas Técnicas num. 17/90, Junta de Andalucía, Consejería de Agricultura y Pesca, Seville, Spain, 1990.

López-Vicente, M., Gómez, J. A., Guzmán, G., Calero, J., and García-Ruiz, R.: The role of cover crops in the loss of protected and non-protected soil organic carbon fractions due to water erosion in a Mediterranean olive grove, Soil and Tillage Research, 213, 105119, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2021.105119, 2021.

Mabit, L., Chhem-Kieth, S., Toloza, A., Vanwalleghem, T., Bernard, C., Amate, J. I., González De Molina, M., and Gómez, J. A.: Radioisotopic and physicochemical background indicators to assess soil degradation affecting olive orchards in southern Spain, Agric. Ecosyst. Environ., 159, 70–80, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2012.06.014, 2012.

MAPA: Encuesta sobre Superficies y Rendimientos de Cultivos (ESYRCE): Análisis de las plantaciones de olivar en España 2024, Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación, https://www.mapa.gob.es/dam/mapa/contenido/estadisticas/temas/estadisticas-agrarias/2.agricultura/1.-encuesta-sobre-superficies-y-rendimientos-de-cultivos--esyrce/informes-sectoriales/olivar2024.pdf (last access: 30 January 2026), 2024.

Márquez-García, F., Hayas, A., Peña, A., Ordóñez-Fernández, R., and González-Sánchez, E. J.: Influence of cover crops and tillage on organic carbon loss in Mediterranean olive orchards, Soil Tillage Res., 235, 105905, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2023.105905, 2024.

McLeod, J. S., Whittaker, A. C., Bell, R. E., Hampson, G. J., Watkins, S. E., Brooke, S. A. S., Rezwan, N., Hook, J., Zondervan, J. R., Ganti, V., and Lyster, S. J.: Landscapes on the edge: River intermittency in a warming world, Geology, 52, 512–516, https://doi.org/10.1130/G52043.1, 2024.

Milazzo, F., Francksen, R. M., Zavattaro, L., Abdalla, M., Hejduk, S., Enri, S. R., Pittarello, M., Price, P. N., Schils, R. L. M., Smith, P., and Vanwalleghem, T.: The role of grassland for erosion and flood mitigation in Europe: A meta-analysis, Agric. Ecosyst. Environ., 348, 108443, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2023.108443, 2023.

Ordóñez-Fernández, R., Rodríguez-Lizana, A., Espejo-Pérez, A. J., González-Fernández, P., and Saavedra, M. M.: Soil and available phosphorus losses in ecological olive groves, European Journal of Agronomy, 27, 144–153, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2007.02.006, 2007.

Palese, A. M., Ringersma, J., Baartman, J. E. M., Peters, P., and Xiloyannis, C.: Runoff and sediment yield of tilled and spontaneous grass-covered olive groves grown on sloping land, Soil Res., 53, 542, https://doi.org/10.1071/SR14350, 2015.

Panagos, P., Borrelli, P., Poesen, J., Ballabio, C., Lugato, E., Meusburger, K., Montanarella, L., and Alewell, C.: The new assessment of soil loss by water erosion in Europe, Environ. Sci. Policy, 54, 438–447, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.08.012, 2015.

Parras-Alcántara, L., Lozano-García, B., Keesstra, S., Cerdà, A., and Brevik, E. C.: Long-term effects of soil management on ecosystem services and soil loss estimation in olive grove top soils, Sci. Total Environ., 571, 498–506, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.07.016, 2016.

Peñuela, A. and Milazzo, F.: Soil erosion in Mediterranean Olive Groves – A literarure review – Dataset, Zenodo [data set, code], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17952722, 2025.

Peñuela, A., Hayas, A., Infante-Amate, J., Ruiz-Montes, P., Temme, A., Reimann, T., Peña-Acevedo, A., and Vanwalleghem, T.: A multi-millennial reconstruction of gully erosion in two contrasting Mediterranean catchments, CATENA, 220, 106709, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2022.106709, 2023.

Raglione, M., Toscano, P., Angelini, R., Briccoli-Bati, C., Spadoni, M., De Simone, C., and Lorenzini, P.: Olive yield and soil loss in hilly environment of Calabria (Southern Italy). Influence of permanent cover crop and ploughing, in: Proceedings of the International Meeting on Soils with Mediterranean Type of Climate, Barcelona, Spain, July 1999.

Renard, K. G.: Predicting soil erosion by water: a guide to conservation planning with the Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE), US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, https://doi.org/10.1201/9780203739358-5, 1997.

Repullo-Ruibérriz De Torres, M. A., Ordóñez-Fernández, R., Giráldez, J. V., Márquez-García, J., Laguna, A., and Carbonell-Bojollo, R.: Efficiency of four different seeded plants and native vegetation as cover crops in the control of soil and carbon losses by water erosion in olive orchards, Land Degrad. Dev., 29, 2278–2290, https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.3023, 2018.

Rodrigo-Comino, J., Giménez-Morera, A., Panagos, P., Pourghasemi, H. R., Pulido, M., and Cerdà, A.: The potential of straw mulch as a nature-based solution for soil erosion in olive plantation treated with glyphosate: A biophysical and socioeconomic assessment, Land Degrad. Dev., 31, 1877–1889, https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.3305, 2020.

Rodríguez Sousa, A. A., Muñoz-Rojas, J., Brígido, C., and Prats, S. A.: Impacts of agricultural intensification on soil erosion and sustainability of olive groves in Alentejo (Portugal), Landsc. Ecol., 38, 3479–3498, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-023-01682-2, 2023.

Sastre, B., Barbero-Sierra, C., Bienes, R., Marques, M. J., and García-Díaz, A.: Soil loss in an olive grove in Central Spain under cover crops and tillage treatments, and farmer perceptions, J. Soils Sediments, 17, 873–888, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-016-1589-9, 2017.

Smith, H. G., Peñuela, A., Sangster, H., Sellami, H., Boyle, J., Chiverrell, R., Schillereff, D., and Riley, M.: Simulating a century of soil erosion for agricultural catchment management, Earth Surf. Process. Landf., 43, 2089–2105, https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.4375, 2018.

Taguas, E. V., Ayuso, J. L., Peña, A., Yuan, Y., and Pérez, R.: Evaluating and modelling the hydrological and erosive behaviour of an olive orchard microcatchment under no-tillage with bare soil in Spain, Earth Surf. Process. Landf., 34, 738–751, https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.1775, 2009.

Taguas, E. V., Peña, A., Ayuso, J. L., Pérez, R., Yuan, Y., and Giráldez, J. V.: Rainfall variability and hydrological and erosive response of an olive tree microcatchment under no‐tillage with a spontaneous grass cover in Spain, Earth Surf. Process. Landf., 35, 750–760, https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.1893, 2010.

Taguas, E. V., Moral, C., Ayuso, J. L., Pérez, R., and Gómez, J. A.: Modeling the spatial distribution of water erosion within a Spanish olive orchard microcatchment using the SEDD model, Geomorphology, 133, 47–56, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2011.06.018, 2011.